The introduction of the forms chapter in HTML 4.01 reads: “An HTML form is a section of a document containing normal content, markup, special elements called controls (checkboxes, radio buttons, menus, etc.), and labels on those controls. Users generally ‘complete’ a form by modifying its controls (entering text, selecting menu items, etc.), before submitting the form to an agent for processing (e.g., to a web server, to a mail server, etc.).”

The defining element for HTML forms is named, not too surprisingly,

form. This element

describes some important aspects of the form, including where and how

to submit data. The content of this element consists of regular HTML

markup, as well as controls.

Forms represent a structured exchange of data. In HTML forms, the structure of the collected data, called a form data set, is a set of name/value pairs. The names and values that are included in this set are solely determined by the controls present within the form, so that adding a new control element, as well as adding to the user interface, also adds a new name/value pair to the data set. Many authors take for granted this basic violation of the separation between the data layer and the user interface layer—a problem that XForms has gone to considerable lengths to alleviate.

Which control types are available in HTML forms? The following sections will answer this question.

The workhorse of HTML forms, this control permits the entry of any character data. Text input controls accept a string value and contribute it to the form data set. Example 1-1 shows the XHTML code needed to produce a basic single-line text control, and Figure 1-1 shows the result.

A more complex variation of text entry is when multiple lines of text need to be entered. For this purpose, HTML forms includes a separate form control that is typically larger than standard text input controls and offers special handling of multiple-line text. Multi-line text input controls contribute to the form data set exactly as do single-line text input controls. Example 1-2 shows the XHTML code for a multi-line text control, and Figure 1-2 shows the result.

Another variation of text entry is for sensitive data, such as a password, that could be harmful to display on the screen where someone could “shoulder surf,” or covertly observe, and thus compromise security measures. It is important to note that this control provides only a casual level of security in the presentation: it does not, for example, provide any data encryption. Password text input controls contribute to the form data set exactly as do text input controls. Example 1-3 shows the XHTML code needed for a password control, and Figure 1-3 shows the result.

These controls are similar to buttons, but when activated have the effect of built-in processing (to submit or reset the form, respectively). Reset controls aren’t supposed to contribute to the form data set, but up to one submit button can. This can be useful, when there are multiple submit buttons, in determining which one initiated the submission process. Example 1-4 shows the XHTML code needed for submit and reset controls, and Figure 1-4 shows the result.

The effect of activating a button is

to invoke a call in a scripting language. A button can be specified

in two slightly different ways, with the button

syntax being slightly more expressive. If a value is assigned to the

button, it will be contributed unchanged to the form data set (not

the most useful functionality, but there if you need it). Example 1-5 shows the XHTML code for a button control, and

Figure 1-5 shows the

result.

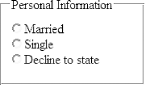

Named after the mechanical controls on old radios, this common control requires that a single option always be selected, and thus is almost always used as a group of controls with the same name. The HTML specification encourages authors to ensure that a particular choice is initially selected, but in practice authors usually don’t select a particular choice, resulting in “undefined” behavior. (One common implementation choice is to provide a temporary exception to the one-thing-must-always-be-selected rule, but it isn’t safe to rely on this behavior.) A group of radio buttons provides a single value representing the current selection to the form data set. Example 1-6 shows the XHTML code for a radio button group, and Figure 1-6 shows the result.

Example 1-6. XHTML code for a radio button group

<input type="radio" name="car" value="0"/> None<br/> <input type="radio" name="car" value="1"/> 1 car<br/> <input type="radio" name="car" value="2"/> 2 cars<br/> <input type="radio" name="car" value="3"/> 3 cars<br/> <input type="radio" name="car" value="4"/> 4 cars<br/> <input type="radio" name="car" value="many"/> 5 or more<br/>

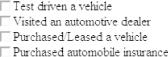

This simple on/off control has become familiar to computer users everywhere. Often, this control is used in a group which uses the same name, which allows for a select-zero-or-more behavior, though solo checkboxes are common as well. Only checkboxes that are checked contribute to the form data set. In cases where multiple checkboxes share the same name and are checked, the form data set will contain multiple entries with the same name and each selected value. Example 1-7 shows the XHTML code for a checkbox group, and Figure 1-7 shows the result.

Example 1-7. XHTML code for a checkbox group

<input type="checkbox" name="referBy" value="td"/> Test driven a vehicle<br/> <input type="checkbox" name="referBy" value="dlr"/> Visited an autotmotive dealer<br/> <input type="checkbox" name="referBy" value="veh"/> Purchased/Leased a vehicle<br/> <input type="checkbox" name="referBy" value="ins"/> Purchased automobile insurance<br/>

Commonly called a

listbox or drop-down menu,

this control enforces a single selection out of several options. In

effect, this control provides another way to achieve the same

function as radio buttons, but with a different visual presentation.

As is the case with radio buttons, an initial state that

doesn’t explicitly select some initial choice is

“undefined,” though existing

implementations usually allow an initial nothing-selected state.

Single-select menus use one

option

child element for each option, which can include both a display value

and a storage value. The storage value representing the current

selection is provided to the form data set. Example 1-8 shows the XHTML code for a single-select

control, and Figure 1-8 shows the

result.

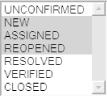

Adding an attribute to the

select element enables

the control to accept multiple selections, or even to select nothing

at all. In this configuration, this control can achieve the same

function as a group of checkbox controls, but with a different

presentation. As with checkboxes, if any options are selected, this

control provides the display value of each selection to the form data

set. Example 1-9 shows the XHTML code for a

multiple-select control, and Figure 1-9 shows the

result.

Example 1-9. XHTML code for a multiple-select control

<select multiple="multiple"> <option value="0">UNCONFIRMED</option> <option selected="selected" value="1">NEW</option> <option selected="selected" value="2">ASSIGNED</option> <option selected="selected" value="3">REOPENED</option> <option value="4">RESOLVED</option> <option value="5">VERIFIED</option> <option value="6">CLOSED</option> </select>

A more recent addition to HTML was the ability to select a local file to submit along with the rest of the form data. This control contributes binary data into the form data set, which has implications on the wire format used to submit data, as discussed later. The filename selected is also included, in a secondary way, in the submitted data. Example 1-10 shows the XHTML code for a file select control, and Figure 1-10 shows the result.

Often, a form needs to hold more data than what is visible, in order to track state or earlier interactions. This control has no user interface effect, but contributes to the form data set. Example 1-11 shows the XHTML code for a hidden control.

Finally, the HTML specification defines a way for additional controls, such as plug-ins or Java applets, to participate in forms. This approach, however, never gained popularity, although clever programmers have used scripting and dynamic HTML to accomplish many of the same goals.

Printed forms

make extensive use of labels as directions for filling out the

document, which is good, since most people don’t

read the regular instructions, anyway. HTML forms are no different. A

label element can be

associated with any control, either by wrapping the

label around the control, or by referencing an ID

unique to the form control. When connected this way, the label

becomes an extension of the control, which helps make forms more

usable. For example, a radio button label is a much easier target to

click on than the tiny circular control itself. When the label is

properly connected, clicking it has the same effect as clicking the

related control.

Nobody is sure exactly why, but the simple practice of using

label elements has failed to catch on with

authors. As a result, many HTML forms still use tables and other

inaccessible techniques where text associated with a form control

might visually appear nearby the control, but is actually defined in

some unrelated markup structure, such as a different table cell. That

kind of document is a major obstacle for non-visual users to figure

out, since the visual proximity of items is the only connection

between form controls and labels.

Groups of radio buttons pose another problem for labeling. Each radio

button can have an individual label, but what about labeling the

overall group? For this purpose, HTML forms include a general-purpose

grouping element called

fieldset,

the first child of which may be

legend,

which is another kind of label. Example 1-12 shows

the XHTML code for a fieldset, and Figure 1-11 shows

the result.

Using a keyboard to get around in a form is not only an accessibility feature, but also a convenience for people who need to fill large numbers of forms or lengthy forms. All controls accept two attributes to help define a keyboard interface:

-

accesskey Defines a character that can be used in conjunction with a system-dependent key (

Alton Windows,Cmdon Mac, etc.), in order to navigate directly to a particular form control.-

tabindex Taken as a whole,

tabindexattributes form a navigation sequence over the form. Thus, pressing Tab or Shift+Tab brings you to the next or previous control.

Often it is necessary in an

electronic form to have a control that displays, but

doesn’t allow changes to, a piece of data. This can

be accomplished through an attribute called

readonly, which unfortunately only applies to text

input controls. When a control is read-only, it is still possible to

navigate to it, and any data present will still be submitted.

The disabled attribute enforces a stronger

prohibition. Any control, even lists, radio buttons, or checkboxes,

can be disabled, in which case the browser gives the control a

distinctive “grayed out”

appearance, indicating its unavailability. It is not possible to

navigate to a disabled control, nor will it participate in data

submission. Effectively, the control is not part of the form anymore

(although it is still available to scripting).

Except for the file upload control, it’s possible to provide initial data for all form controls, but keeping track of the differing form control types is complicated. Here are some of the different control types and the data they accept:

Inserting initial data is a major bottleneck in large-scale projects involving forms, both in terms of processing time and in opportunities for bugs to appear. The typical approach is to have a template language that is processed by an application server, effectively doing a large search-and-replace operation before delivering every page containing forms. Workflow and routing scenarios, where submitted data is sent from one user’s desktop to another, are similarly burdened with large amounts of templating and tricks to populate forms in advance.

Usually,

the primary purpose of a form is to submit data. The original, and

still most popular, encoding for this is called

urlencoded,

and is represented by the Internet media type

application/x-www-form-urlencoded. In this

encoding, spaces become plus signs, and any other reserved characters

become encoded as a percent sign and hexadecimal digits, as defined

in RFC 1738.

One unfortunate aspect of this definition is that it

doesn’t describe how to encode anything beyond

simple ASCII characters. Some implementations have used the document

encoding to control this process, but interoperability has remained

elusive.

A second encoding became necessary with the introduction of the file

upload control and the binary data this introduced into the form data

set. This is called

multipart/form-data,

and is based on the MIME format defined in RFC 2388.

This format allows for much more efficient representation of binary

and non-ASCII data.

One final consideration in form submission is how the data gets submitted. The HTML specification defines submission through the HTTP methods GET and POST and also includes an example of email, through the mailto: URI scheme. The HTTP specification gives some specific advice on when to use GET versus POST, which we will consider later.

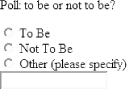

Example 1-13 shows a simple, but typical, HTML form. Figure 1-12 shows how this form is rendered.

Example 1-13. XHTML code for a typical XHTML form

<form action="http://example.com/cgi-bin/submit-here" name="shake-poll"> <p>Poll: to be or not to be?</p> <input type="radio" name="thequestion" id="radio1" value="b"/> <label for="radio1">To Be<label><br/> <input type="radio" name="thequestion" id="radio2" value="n"/> <label for="radio2">Not To Be<label><br/> <input type="radio" name="thequestion" id="radio3"/> <label for="radio3">Other (please specify)<label><br/> <input type="text" name="othersel"/> </form>

Get XForms Essentials now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.