Much as archaeologists examining an ancient site often find the ruins of multiple cities, each built on top of the previous one, neuroscientists peering into the brain find newer biological hardware built over the old stuff. In this section, you'll get the chance to peel back the layers.

The human brain is, like all the products of evolution, a work-in-progress. Although we won't see the human brain change in our lifetimes, millions of years of evolution have left their fingerprints all over it. Here's what's been happening:

The human brain has grown, becoming physically larger. In fact, there's a strong case that humans suffer far more pain giving birth than almost any other animal because of our comparatively huge heads, which we need to carry around our outsized brains.

Existing brain hardware has been adapted for different uses. The human brain is remarkably flexible. In deaf children, it can assign brain parts normally used for hearing to other tasks, like understanding sign language. In blind children, the brain can recruit the speech processing regions to interpret the tactile sensation of Braille letters. Over millions of years, similar but more profound shifts can occur. For example, many researchers believe that human speech hijacked some serious brain space in our early ancestors, and crowded out other skills.

New features have been bolted on top of old ones. It's much easier for evolution to change what's already there than create a whole new brain from scratch. That means there's some deep, dark animal ancestry in your brain. If evolution were a building contractor, you'd find it leaving a few frightening things in the basement.

In the following section, you'll slice open your brain (metaphorically speaking) and get a closer look.

Note

No one knows why big-brained humans won the evolutionary arms race. Although it's tempting to conclude that smarter humans could build better tools (and therefore catch more nutritious animals), the brain has a significant evolutionary disadvantage—it's a hugely expensive energy hog. One of the more likely explanations for our success is that bigger human brains helped us attract mates and negotiate sticky group dynamics. In other words, we're all the descendants of a few sexy nerds.

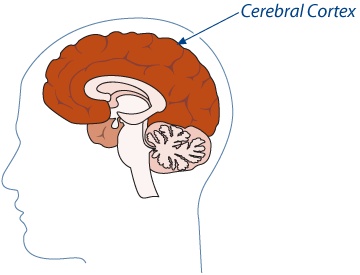

The outer layer of your brain is the cerebral cortex. It powers conscious perception, abstract reasoning, speech, and creativity. It also accounts for over two thirds of your brain's weight.

Although the cerebral cortex looks like a heavily wrinkled cauliflower, it's more like a crumpled sheet of paper. Its deep grooves and bulges allow the brain to cram in many more neurons than the less wrinkled brains you'll find in other animals. If you were able to stretch your cerebral cortex out flat on your lap, you'd find that it has about the same surface area as a page of newsprint from the New York Times. However, it's a bit thicker, and doesn't offer nearly as good a read.

Note

The previous picture shows the brain split down the middle. This view makes it clear that the cerebral cortex wraps along the top, front, and back of your brain. What the figure doesn't show is how the cerebral cortex also wraps around the sides of your brain. (To see the outside view of your brain, which is nearly all cerebral cortex, see A First Look at Your Brain.)

Under the cerebral cortex, you'll find a set of older brain structures. These brain regions play a key role in memory (see Chapter 5) and emotional drives (such as the pleasure-seeking and pain-avoiding behavior you'll learn about in Chapter 6).

Sometimes, these brain structures are grouped together into a ring-shaped region called the limbic system. However, these days many neuroscientists doubt that they actually make up a distinct system that's separate from the rest of the brain. Instead, they prefer to examine each structure on its own merits.

Buried deep inside your brain are its oldest structures, including the brainstem and the cerebellum.

The brainstem looks like little more than a glorified lump at the top of the spinal cord. It controls body functions that have little conscious control, like breathing, hunger (see Chapter 2), and body temperature. It also plays the role of a massive conduit by funneling all the signals that travel between your brain and your body.

At the back of the brainstem is a fist-size growth that looks like a miniature brain. This region is the cerebellum, and it coordinates balance and movement. New research also suggests that the cerebellum plays a support role for other, more complex tasks. One theory is that it coordinates different regions of the brain so they can perform their work more efficiently.

It's common to describe the deepest regions of the brain as older, because these areas evolved first, in some distant species that was ancestor to us as well as many other modern creatures. For the same reason, we share these brain parts—in an extensively altered form—with other species. For example, bird and reptile brains appear to have a similar brainstem to ours but a vastly shrunken cerebral cortex. Orangutans, which are much closer relatives, have brains that are strikingly similar in almost all their component parts, but much smaller than ours.

It's a bit fanciful to imagine (as some early brain theories did) that the different layers of our brains are continuously at war. However, it's not so hard to picture a delicate balance between instinctive, ritualistic, and reactive behaviors that are rooted in the old brain systems and the morality, social sense, and problem solving that draw on the newer brain parts. In fact, it just might explain the paradox of a species that is equally at home in the symphony hall as it is on the field of war.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the human brain is a relatively recent development, with its sudden increase in size and pumped-up cerebral cortex happening just a few hundred thousand years ago. However, from the perspective of an individual human like yourself, the human brain is unimaginably old. This poses some sticky challenges, because the brain's survival strategies just aren't designed for 21st-century living.

This combination of old brain and new world hints at two of the key themes you'll explore throughout this book:

Your brain often works subconsciously. As renowned neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux puts it, consciousness and language are "new kids on the evolutionary block." As the human brain evolved with its ever-expanding cerebral cortex, it became able to perceive, describe, and reflect on its own actions—many of which are unconscious and nonverbal. So don't be surprised when you find that your brain does many things without your consent, and many more without your realization. You may be able to understand what's taking place in the basement of your brain, but you can't always control it.

Your brain's logic doesn't always serve you well. Every dieter knows that the brain's built-in circuitry can lead to trouble when confronting a larger-than-life billboard for the nearest fast-food chain. The problem here is that the brain has been honed by millions of years of evolution to be the perfect tool—for wandering groups of hunter-gatherers in the African savannah. For our ancestors, a good meal was hard to come by. But in the modern world where rich, nutrient dense foods are plentiful, the brain's natural response ("Eat Now!") can cause more harm than good. Similarly, it may be that certain brain disorders (say, obsessive-compulsive disorder) and some less-than-pleasant aspects of a properly functioning brain (like stress and nightmares) are the result of hardwired circuitry in older regions of the brain.

As you'll see in this book, your brain includes built-in circuitry that makes office politics seem like a life-or-death struggle (Chapter 6), tosses important facts out of your memory if they aren't charged with emotion (Chapter 5), and urges you to eat waistband-defying amounts of high-calorie snacks (Chapter 2). Sometimes, you can learn to compensate for your brain or work around its limitations. Other times, you'll be forced to accept its eccentricities.

Note

Evolution is a powerful brain-shaping force, but it's slow. It's a little bit like Microsoft asked you to create the world's most fantastic accounting software, you whipped it up, took a vacation for 100,000 years, and then came back with the package. Your program might still do the job, but it wouldn't be ideal.

Get Your Brain: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.