Chapter 1. Ajax Basics

Remember when users called the Internet the “world wide wait?” Way back in the Neolithic era of the Web? With some applications, that aspect of the Web hasn’t really changed that much: fill out form, click button, web page goes away, wait, page refreshes, correct mistake, click, wait, wait... You’ve been stuck in this limbo before.

A number of recent web sites, however, such as many of the cool mapping applications that have evolved of late, require much greater responsiveness in the way they interact with users. The old, conventional way of handling user interaction is to have the entire page “go away” with every click, with the new page reappearing in the browser view only when the server’s response is finally complete. However, some new applications require small pieces of the web page to change instantaneously, without the entire page reloading.

For example, if you have ever used Google Maps, the way you can drag outlying regions into your view conveys the impression that you have all of the maps stored locally on your computer, for your effortless manipulation. Imagine how unpopular this application would be if every time you tried to “drag” the map the page disappeared for a few (long) moments while the browser waited for another server response. The application would be so sluggish that no one would use it. So what’s the magic that makes this work?

It’s Not a Floor Wax

A blend of well-known technologies and a nifty JavaScript tool form the basis of a snappier and more powerful application model for the Web. If you’re afraid of acronym overload, don’t worry—this one’s easy. It’s called Ajax, which stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML.

Ajax is neither a floor wax nor a desert topping (nor, indeed, a lemon-scented cleaning product!). It’s a blend of a number of standard technologies already familiar to developers and designers:

JavaScript, a programming language that adds dynamic scripting to web pages. JavaScript code can be embedded in a web page to allow the page to implement cool new behaviors with a technique called client-side scripting. This technique is almost as old as the Web itself.

XMLHttpRequest, a JavaScript object with an application programming interface (API) that can connect with a server using the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP). A lot of the Ajax magic is propelled by this piece of code, which all the major browsers (such as Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer 6, Safari 1.3 and 2.0, and Opera 7.6) support. The asynchronous part of Ajax derives from this object’s characteristics.[1]Extensible Markup Language (XML), a language designed to define other languages. The

XMLHttpRequestobject can handle the server response in standard XML format as well as plain text.HTML and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), which control what the user sees on a web page. Web developers can use JavaScript to make dynamic changes to the visual interface by programming HTML elements and CSS styles.

The Document Object Model (DOM), a model that represents an XML file or web page as a set of related objects that can be dynamically manipulated, even after the user has downloaded the page. The web page view is structured as a tree hierarchy made up of a root node, the parent, and its various branches, or children. Each HTML element is represented by a node or branch, which is accessible via JavaScript. We show a lot (a lot!) of DOM programming in these hacks.

Extensible Stylesheet Language and Transformation (XSLT), a templating technology for transforming the display of XML information for a receiving client.

Ajax is far from new, as these are relatively old technologies.

Microsoft issued the first implementation of a JavaScript object that

makes HTTP requests, often referred to as the XMLHTTP object, with Version 5.0 of the

Internet Explorer browser (as of this writing, IE is on Version 6, with

v7 in a beta release).

The plethora of new web applications that use Ajax, however, suggests that this group of technologies has morphed into a new web model. “Web 2.0” is next-generation-speak encompassing Ajax, a form of Rich Internet Application (so called because much of the application’s functionality can reside in the client browser). Examples of these applications are Google Maps, Gmail, a collaboration suite called Zimbra, an interesting personal search-engine tool called Rollyo (http://www.rollyo.com), and one of the first interactive web maps, this one of Switzerland (see http://map.search.ch/index.en.html). The number of Ajax applications is growing very rapidly. You can find a short list on Wikipedia, at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_websites_using_Ajax.

Handle with Care

Of course, Ajax is not for everyone (particularly those dessert topping fans!). Because Ajax technology can dynamically alter a web page that has already been downloaded, it may interfere with certain functions near and dear to many users, such as creating bookmarks for browser views. For example, in the absence of fancy scripting solutions, the dynamic changes you make with DOM in an existing web page cannot be linked to with a URL that you can send to your friends or save for later. (Both “Fix the Browser Back Button in Ajax Applications” [Hack #68] and “Handle Bookmarks and Back Buttons with RSH” [Hack #69] should help shed light on these issues and provide some hackable solutions.)

A number of the cool Ajax tips described in this book alter the

behavior of many familiar web widgets, such as select lists, textareas, text fields, and radio buttons that

submit their own data and talk to servers behind the scenes. However,

bear in mind that Ajax-powered widgets should be first and foremost

usable, and always avoid confusing and irritating

web users.

XMLHttpRequest

At the center of many of the hacks in this book is the XMLHttpRequest object, which allows JavaScript

to fetch bits of server data while the user is happily playing with the

rest of your application. This object has its own API, which we will

summarize in this introduction.

“Detect Browser Compatibility with the Request Object” [Hack #1] covers setting up the request object in JavaScript. Once the object is initialized, it has several methods and properties that you can use in your own hacks.

Tip

A common practice among programming types is to call the

functions that are associated with particular JavaScript

objects “methods.” The XMLHttpRequest object’s methods include

open(), send(), and abort().

The following list shows the properties supported by the request objects defined by most of the major browsers, such as Internet Explorer 5.0 and later, Safari 1.3 and 2.0, Netscape 7, and Opera’s latest releases (such as Opera 8.5). Mozilla Firefox’s request object has additional properties and methods not shared by the request objects of other major browsers,[2] but it also supports all of the following:

onreadystatechangeCallback function; the function assigned to this property is called whenever

readyStatechanges.readyStateNumber;

0means uninitialized,open()has not yet been called;1means loading,send()has not been called;2means loaded,send()has been called, and headers/status are available;3means interactive,responseTextholds partial data;4means completed.responseTextstring; the plain text of the response.responseXMLDOM

Documentobject; an XML return value.statusResponse status code, such as

200(Okay) or404(Not Found).statusTextstring; the text associated with the HTTP response status.

The methods supported include:

abort()void; cancels the HTTP request.getAllResponseHeaders()string; returns all of the response headers in a preformatted string (see “Dig into the HTTP Response” [Hack #9]).getResponseHeader(string header)string; returns the value of the specified header.open(string url,string asynch)void; prepares the HTTP request and specifies whether it is asynchronous or not.send(string)void; sends the HTTP request.setRequestHeader(string header,string value)void; sets a request header, but you must callopen()first!

Detect Browser Compatibility with the Request Object

Use JavaScript to set up Microsoft’s and the Mozilla-based browsers’ different request objects.

Browser compatibility is an important consideration. You have to make sure the “engine” behind Ajax’s server handshake is properly constructed, but you can never predict which browsers your users will favor.

The programming tool that allows Ajax applications to make HTTP

requests to a server is an object that you can use from within

JavaScript code. In the world of Firefox and Netscape (as well as Safari

and Opera), this object is named XMLHttpRequest. However, continuing with the

tradition established by IE 5.0, recent vintages of Internet Explorer

implement the software as an ActiveX

object named Microsoft.XMLHTTP or

Msxml2.XMLHTTP.

Tip

Microsoft.XMLHTTP and

Msxml2.XMLHTTP refer to different

versions of software components that are a part of Microsoft XML Core

Services (MSXML). Here’s what our contributing IE expert says on this

matter:

“If you use Microsoft.XMLHTTP, the ActiveXObject wrapper will try to initialize

the last known good version of the object that has this program (or

“prog”) ID. This object, in theory, could be MSXML 1.0, but almost no

one these days has that version because it has been updated via

Windows Update, IE 6, or another means. MSXML 1.0 was very

short-lived. If you use MSXML2.XMLHTTP, that signifies to the

wrapper to use at least MSXML 2.0 libraries. Most developers do not

need to use a specific version of MSXML, such as MSXML2.XMLHTTP.4.0 or MSXML2.XMLHTTP.5.0.”

Although Microsoft and the engineers on the Mozilla project have

chosen to implement this object differently, we will refer to the

ActiveX and XMLHttpRequest objects simply as “request objects” throughout this book, because they have

very similar functionality.

As a first step in using Ajax, you must check if the user’s

browser supports either one of the Mozilla-based or ActiveX-related request objects, and then

properly initialize the object.

Using a Function for Checking Compatibility

Wrap the compatibility check inside a JavaScript

function, then call this function before you make any HTTP requests

using the object. For example, in Mozilla-based browsers such as

Netscape 7.1 and Firefox 1.5 (as well as in Safari 2.0 and Opera 8.5),

the request object is available as a property of the top-level

window object. The reference to

this object in JavaScript code is window.XMLHttpRequest. The compatibility check

for these browser types looks like this:

if(window.XMLHttpRequest){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open("GET",theURL,true);

request.send(null);

}The JavaScript variable request is a top-level variable that will

refer to the request object.

Tip

As an alternative model, the open-source library

Prototype uses object-oriented JavaScript

to wrap the request object into its own object, as in the object

Ajax.Request (see Chapter 6).

If the browser supports XMLHttpRequest, then:

if(window.XMLHttpRequest)returnstruebecause theXMLHttpRequestis notnullorundefined.The object will be instantiated with the

newkeyword.Its

onreadystatechangeevent listener (see the section “XMLHttpRequest” earlier in this chapter) will be defined as a function namedhandleResponse().The code calls the request object’s

open()andsend()methods.

What about Internet Explorer users?

Tip

Microsoft Internet Explorer–related blogs mentioned, at the time this book went to publication, that IE 7 would support a native XMLHttpRequest object.

In this case, the window.XMLHttpRequest object will not exist

in the browser object model. Therefore, another branch of the if test is necessary in your code:

else if (window.ActiveXObject){

request=new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

if (! request){

request=new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

}

if(request){

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open(reqType,url,true);

request.send(null);

}

} This code fragment tests for the existence of the

top-level window object ActiveXObject, thus signaling the use of

Internet Explorer. The code then initializes the request using two of

a number of possible ActiveX program IDs (here, Microsoft.XMLHTTP and Msxml2.XMLHTTP).

You can get even more fine-grained when testing for different

versions of the IE request object, such as Msxml2.XMLHTTP.4.0. In the vast majority of

cases, however, you will not be designing your application based on

various versions of the MSXML libraries, so the prior code will

suffice.

The code then makes one final check for whether the request

object has been properly constructed (if(request){...}).

Given three chances, if the request variable is still null or undefined, your browser is really out of

luck when it comes to using the request object for Ajax!

Here’s an example of an entire compatibility check:

/* Wrapper function for constructing a request object.

Parameters:

reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST.

url: The URL of the server program.

asynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. */

function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch){

//Mozilla-based browsers

if(window.XMLHttpRequest){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else if (window.ActiveXObject){

request=new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

if (! request){

request=new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

}

}

//the request could still be null if neither ActiveXObject

//initialization succeeded

if(request){

initReq(reqType,url,asynch);

} else {

alert("Your browser does not permit the use of all "+

"of this application's features!");

}

}

/* Initialize a request object that is already constructed */

function initReq(reqType,url,bool){

/* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open(reqType,url,bool);

request.send(null);

}“Use the Request Object to

POST Data to the Server” [Hack #2] shows how to implement a

POST request with XMLHttpRequest.

Use the Request Object to POST Data to the Server

Step beyond the traditional mechanism of posting your user’s form values.

This hack uses the POST HTTP request method to send data, communicating with the server without disrupting the user’s interaction with the application. It then displays the server’s response to the user. The difference between this hack’s approach to posting data and the typical form-submission method is that with Ajax, the page is not altered or refreshed when the application connects with the server to POST it the data. Thus, the user can continue to interact with the application without waiting for the interface to be rebuilt in the browser.

Imagine that you have a web portal in which several regions of the page or view provide the user with a variety of services. If one of these regions involves posting data, the entire application might have a more responsive feel if the POST request happens in the background. This way, the entire page (or segments of it) does not have to be refreshed in the browser.

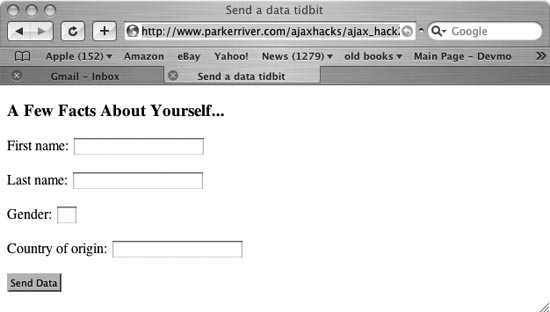

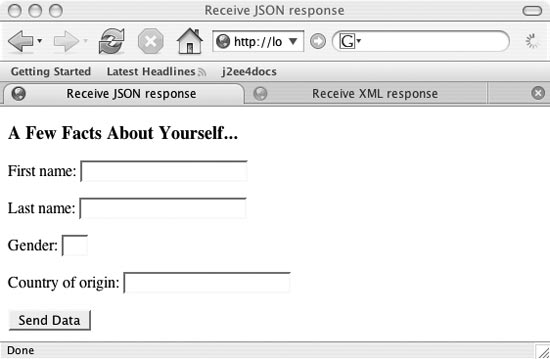

The example web page used in this hack is a simple one. It requests users to enter their first and last names, gender, and country of origin, and then click a button to POST the data. Figure 1-1 shows what the web page looks like in a browser window.

Here’s the code for the HTML page:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="/parkerriver/js/hack2.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Send a data tidbit</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>A Few Facts About Yourself...</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit="sendData();return false">

<p>First name: <input type="text" name="firstname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Last name: <input type="text" name="lastname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Gender: <input type="text" name="gender" size="2"> </p>

<p>Country of origin: <input type="text" name="country" size="20"> </p>

<p><button type="submit">Send Data</button></p>

</form>

</body>

</html>Tip

You may be wondering about the weird-looking form action="javascript:void%200" part. Because

we are calling JavaScript functions when the form is submitted, we do

not want to give the action

attribute anything but a JavaScript URL that has no return value, such

as "javascript:void 0". We have to

encode the space between void and

0, which is where the %20 comes in. If JavaScript is disabled in

the user’s browser, clicking the submit button on the form has no

effect because the action attribute

does not point to a valid URL. In addition, certain HTML validators

will display warnings if you use action="". Another way of writing this code

is to include the function calls as part of the window.onload event handler in the

JavaScript .js file, which is the

approach used by most hacks in this book.

The first code element of interest is the script tag, which imports the JavaScript code

(in a file named hack2.js). The

form tag’s onsubmit attribute specifies a function called

sendData(), which in turn formats

the data for a POST request (by calling another function, setQueryString()) and sends the data to the

server. For brevity’s sake, we’ve saved the description of checking for

blank fields for a later hack (“Validate a Text Field or textarea for

Blank Fields” [Hack #22]), but web applications should take this

step before they hit the server.

The hack2.js file defines the necessary JavaScript.

Here is the setQueryString() function:

function setQueryString(){

queryString="";

var frm = document.forms[0];

var numberElements = frm.elements.length;

for(var i = 0; i < numberElements; i++) {

if(i < numberElements-1) {

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value)+"&";

} else {

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value);

}

}

}This function formats a POST-style string out of all the form’s input elements. All the name/value pairs are

separated by an & character,

except for the pair representing the last input element in the form. The entire string

might look like:

firstname=Bruce&lastname=Perry&gender=M&country=USA

Now you have a string you can

use in a POST HTTP request. Let’s look at the JavaScript code that sends

the request. Everything starts with the

sendData() function. The code calls this

function in the HTML form tag’s

onsubmit attribute:

var request;

var queryString; //will hold the POSTed data

function sendData(){

setQueryString();

var url="http://www.parkerriver.com/s/sender";

httpRequest("POST",url,true);

}

/* Initialize a request object that is already constructed.

Parameters:

reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST.

url: The URL of the server program.

isAsynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. */

function initReq(reqType,url,isAsynch){

/* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open(reqType,url,isAsynch);

/* Set the Content-Type header for a POST request */

request.setRequestHeader("Content-Type",

"application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8");

request.send(queryString);

}

/* Wrapper function for constructing a request object.

Parameters:

reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST.

url: The URL of the server program.

asynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. */

function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch){

//Mozilla-based browsers

if(window.XMLHttpRequest){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else if (window.ActiveXObject){

request=new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

if (! request){

request=new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

}

}

//the request could still be null if neither ActiveXObject

//initialization succeeded

if(request){

initReq(reqType,url,asynch);

} else {

alert("Your browser does not permit the use of all "+

"of this application's features!");

}

}The purpose of the httpRequest() function is to check which

request object the user’s browser is associated with (see “Detect Browser Compatibility with the

Request Object” [Hack #1]). Next, the code calls initReq(), whose parameters are described in

the comment just above the function definition.

The code request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

specifies the event-handler function that deals with the response. We’ll

look at this function a little later. The code then calls the request

object’s open() method, which

prepares the object to send the request.

Setting Headers

The code can set any request headers after calling

open(). In our case, we have to

create a Content-Type header for a

POST request.

Tip

Firefox required the additional Content-Type header; Safari 1.3 did not.

(We were using Firefox 1.02 at the time of writing this hack.) It is

a good idea to add the proper header because in most cases the

server is expecting it from a POST request.

Here’s the code for adding the header and sending the POST request:

request.setRequestHeader("Content-Type",

"application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8");

request.send(queryString);If you enter the raw queryString value as a parameter, the method

call looks like this:

send("firstname=Bruce&lastname=Perry&gender=M&country=USA");Ogling the Result

Once your application POSTs data, you want to display

the result to your users. This is the responsibility of the handleResponse() function. Remember the code

in the initReq() function:

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

When the request object’s readyState property has a value of 4, signifying that the object’s operations

are complete, the code checks the HTTP response status for the value

200. This value indicates that the

HTTP request has succeeded. The responseText is then displayed in an

alert window. This is somewhat

anticlimactic, but I thought I’d keep this hack’s response handling

simple, because so many other hacks do something more complex with

it!

Here is the relevant code:

//event handler for XMLHttpRequest

function handleResponse(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

alert(request.responseText);

} else {

alert("A problem occurred with communicating between "+

"the XMLHttpRequest object and the server program.");

}

}//end outer if

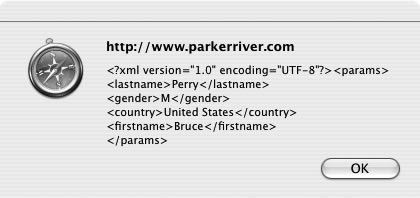

}Figure

1-2 shows what the alert

window looks like after the response is received.

The server component returns an XML version of the POSTed data.

Each parameter name becomes an element name, with the parameter value

as the element content. This POSTed data is nested within params tags. The component is a Java

servlet. The servlet is not the main focus of this hack, but here’s

some code anyway, for the benefit of readers who are curious about

what is happening on the server end:

protected void doPost(HttpServletRequest httpServletRequest,

HttpServletResponse httpServletResponse) throws

ServletException, IOException {

Map reqMap = httpServletRequest.getParameterMap();

String val=null;

String tag = null;

StringBuffer body = new StringBuffer("<params>\\n");

boolean wellFormed = true;

Map.Entry me = null;

for(Iterator iter= reqMap.entrySet().iterator();iter.hasNext();) {

me=(Map.Entry) iter.next();

val= ((String[])me.getValue())[0];

tag = (String) me.getKey();

if (! XMLUtils.isWellFormedXMLName(tag)){

wellFormed=false; break;

}

body.append("<").append(tag).append(">").

append(XMLUtils.escapeBodyValue(val)). append("</").append(tag).append(">\\n");

}

if(wellFormed) {

body.append("</params>");

sendXML(httpServletResponse,body.toString());

} else {

sendXML(httpServletResponse,"<notWellFormedParams />");

}

}The code uses XMLUtils, a Java class from the Jakarta

Commons Betwixt open source package, to check whether the parameter

names are well formed, as well as whether the parameter values contain

invalid XML content and thus have to be escaped. If for some reason

the component is POSTed data that contains nonwell-formed parameter

names (such as na< >me instead of name), the servlet returns an empty XML

element reporting this condition.

Use Your Own Library for XMLHttpRequest

Break out the code that initializes the request object and sends requests to its own JavaScript file.

To cleanly separate the concerns of big Ajax applications, create

a separate file that manages the XMLHttpRequest object, then import that file

into every web page that needs it. At the very least, this ensures that

any necessary changes regarding how the code sets up the request object

have to be made only in this file, as opposed to every JavaScript file

that uses Ajax-style requests.

This hack stores all the request object–related code in a file

called http_request.js. Any web page that uses

XMLHttpRequest can then import this

file in the following way:

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/http_request.js"></script>

Here’s the code for the file, including all the comments:

var request = null; /* Wrapper function for constructing a request object. Parameters: reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST. url: The URL of the server program. asynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. respHandle: The name of the function that will handle the response. Any fifth parameters, represented as arguments[4], are the data a POST request is designed to send.*/function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch,respHandle){ //Mozilla-based browsers if(window.XMLHttpRequest){ request = new XMLHttpRequest(); } else if (window.ActiveXObject){ request=new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP"); if (! request){ request=new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP"); } } //very unlikely, but we test for a null request //if neither ActiveXObject was initialized if(request) { //if the reqType parameter is POST, then the //5th argument to the function is the POSTed data if(reqType.toLowerCase() != "post") { initReq(reqType,url,asynch,respHandle); } else { //the POSTed data var args = arguments[4]; if(args != null && args.length > 0){ initReq(reqType,url,asynch,respHandle,args); } } } else { alert("Your browser does not permit the use of all "+ "of this application's features!"); } } /* Initialize a request object that is already constructed */ function initReq(reqType,url,bool,respHandle){ try{ /* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */ request.onreadystatechange=respHandle; request.open(reqType,url,bool); //if the reqType parameter is POST, then the //5th argument to the function is the POSTed data if(reqType.toLowerCase() == "post") { request.setRequestHeader("Content-Type", "application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8"); request.send(arguments[4]); } else { request.send(null); }}catch (errv) { alert( "The application cannot contact "+ "the server at the moment. "+ "Please try again in a few seconds.\\n"+ "Error detail: "+errv.message); } }

The applications that use this code call the httpRequest() function with four or five (with

POST requests) parameters. You see lots of examples of calling this

function in the other hacks. Here’s another:

var _url = "http://www.parkerriver.com/s/sender";

var _data="first=Bruce&last=Perry&middle=W";

httpRequest("POST",_url,true,handleResponse,_data);The code comments describe the meaning of each of these parameters. The last parameter represents the data that accompanies a POST request.

Tip

A POST HTTP request includes the POSTed data beneath the request-header information. A GET request, on the other hand, appends parameter names/values onto the URL.

If the code is not using POST, the client code uses only the first four parameters. The fourth parameter can be either the name of a function that is declared in the client code (i.e., a response-handling function that appears outside of the http_request.js file) or a function literal. The latter option involves defining a function inside a function call, which is often awkward and difficult to read. However, it is sensible in situations in which the HTTP response handling is short and simple, as in:

var _url = "http://www.parkerriver.com/s/sender";

//a debugging setup

httpRequest("POST",_url,true,function(){alert(request.responseText);});httpRequest() initiates the

same browser detection and setup of XMLHttpRequest for Internet Explorer and

non-Microsoft browsers as described in “Detect Browser Compatibility with the

Request Object” [Hack #1]. initReq() handles the second step of setting

up the request object: specifying the onreadystatechange event handler and calling

the open() and send() methods to make an HTTP request. The

code traps any errors or exceptions thrown by these request method calls

using a try/catch statement. For

example, if the code calls open()

with a URL specifying a different host than that used to download the

enclosing web page, the try/catch

statement catches the error and pops up an alert window.

Finally, as long as the web page imports http_request.js, the request variable is available to code external

to the imported file; request is, in

effect, a global variable.

Warning

request is thus reserved as a

variable name because local variables that use the var keyword will supercede (with

unintentional consequences) the globally used request, as in the following example:

function handleResponse(){ //supercedes the imported request variable var request = null; try{ if(request.readyState == 4){ if(request.status == 200){...

Receive Data as XML

Ajax and server programs provide a DOM Document object that’s ready to go.

Many technologies currently exchange data in Extensible Markup Language format, mostly because XML is a standardized and extensible format widely supported by the software world. Thus, different parties can use existing, well-known technologies to generate, send, and receive XML, without having to adapt to the software tools used by the parties with whom they are exchanging the XML data.

An example is a Global Positioning System (GPS) device that can share the data it has recorded about, say, a hike or a bike ride with a location-aware web application. You just stick the USB cable attached to the GPS device into a USB computer port, launch software that sends the device data to the Web, and that’s it. The data format is usually an XML language that has been defined already for GPS software. The web application and the GPS device “speak the same language.”

Although this book is not the place for an extensive introduction

to XML, you have probably seen these text files in one form or another.

XML is used as a “meta” language that describes and categorizes specific

types of information. XML data starts with an optional XML declaration

(e.g., <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>), followed

by a root element and zero or more child elements. An example is:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <gps> <gpsMaker>Garmin</gpsMaker> <gpsDevice> Forerunner 301 </gpsDevice> </gps>

Here, gps is the root element,

and gpsMaker and gpsDevice are child elements.

Ajax and the request object can receive data as XML, which is very

useful for handling web-services responses that use XML. Once the HTTP

request is complete, the request object has a property named responseXML. This object is a DOM Document object

that your Ajax application can use. Here’s an example:

function handleResponse(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

var doc = request.responseXML;

...

}In the previous code sample, the doc variable is a DOM Document object, offering a similar API to a

browser’s display page. This hack receives XML from a server, then

initiates a little DOM programming with the Document object to pull some information out

of the XML.

Tip

If you just want to see the raw XML text, use the request.responseText property instead.

The HTML file for this hack is basically the same as the one used

in “Use the Request Object to POST

Data to the Server” [Hack #2], but a

div element is added at the end, where the code

displays information about the returned XML. Here’s the code for the

HTML page:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/hack3.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Receive XML response</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>A Few Facts About Yourself...</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit="sendData();return false">

<p>First name: <input type="text" name="firstname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Last name: <input type="text" name="lastname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Gender: <input type="text" name="gender" size="2"> </p>

<p>Country of origin: <input type="text" name="country" size="20"> </p>

<p><button type="submit">Send Data</button></p>

<div id="docDisplay"></div>

</form>

</body>

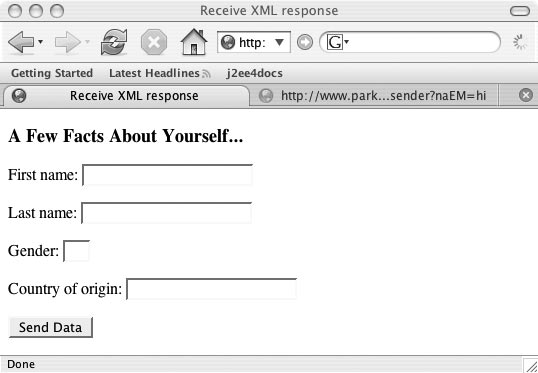

</html>Figure 1-3 shows what the page looks like before the user enters any information.

The JavaScript code in the hack3.js file POSTs its data to a server application, which sends back a response in XML format. The field validation step [Hack #22] has been skipped for the sake of brevity, but web applications using forms should always implement this task.

Like other examples in this chapter, the server program echoes the

parameter names and values back to the client, as in <params><firstname>Bruce</firstname></params>.

“Use the Request Object to POST

Data to the Server” [Hack #2] shows some of the code for the

server component that puts together the return value. This technique

suits our purpose for showing a simple example of programming XML in an

Ajax application:

var request;

var queryString; //will hold the POSTed data

function sendData(){

setQueryString();

var url="http://www.parkerriver.com/s/sender";

httpRequest("POST",url,true);

}

//event handler for XMLHttpRequest

function handleResponse(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

var doc = request.responseXML;

var info = getDocInfo(doc);

stylizeDiv(info,document.getElementById(""docDisplay""));

} else {

alert(""A problem occurred with communicating between ""+

""the XMLHttpRequest object and the server program."");

}

}//end outer if

}

/* Initialize a request object that is already constructed */

function initReq(reqType,url,bool){

/* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open(reqType,url,bool);

request.setRequestHeader(""Content-Type"",

""application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8"");

/* Only works in Mozilla-based browsers */

//request.overrideMimeType(""text/xml"");

request.send(queryString);

}

/* Wrapper function for constructing a request object.

Parameters:

reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST.

url: The URL of the server program.

asynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. */

function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch){

//Snipped...See Hack #1

}

function setQueryString(){

queryString="";

var frm = document.forms[0];

var numberElements = frm.elements.length;

for(var i = 0; i < numberElements; i++) {

if(i < numberElements-1) {

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value)+"&";

} else {

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value);

}

}

}

/* Provide the div element's content dynamically. We can add

style information to this function if we want to jazz up the div */

function stylizeDiv(bdyTxt,div){

//reset DIV content

div.innerHTML="";

div.style.backgroundColor="yellow";

div.innerHTML=bdyTxt;

}

/* Get information about an XML document via a DOM Document object */

function getDocInfo(doc){

var root = doc.documentElement;

var info = "<h3>Document root element name: </h3>"+ root.nodeName;

var nds;

if(root.hasChildNodes()) {

nds=root.childNodes;

info+= "<h4>Root node's child node names/values:</h4>";

for (var i = 0; i < nds.length; i++){

info+= nds[i].nodeName;

if(nds[i].hasChildNodes()){

info+= " : \\""+nds[i].firstChild.nodeValue+"\\"<br />";

} else {

info+= " : Empty<br />";

}

}

}

return info;

}Tip

Mozilla Firefox can use the request.overrideMimeType() function to force

the interpretation of the response stream as a certain mime type, as

in request.overrideMimeType("text/xml").

Internet Explorer’s request object does not have this function. This

function call does not work with Safari 1.3, either.

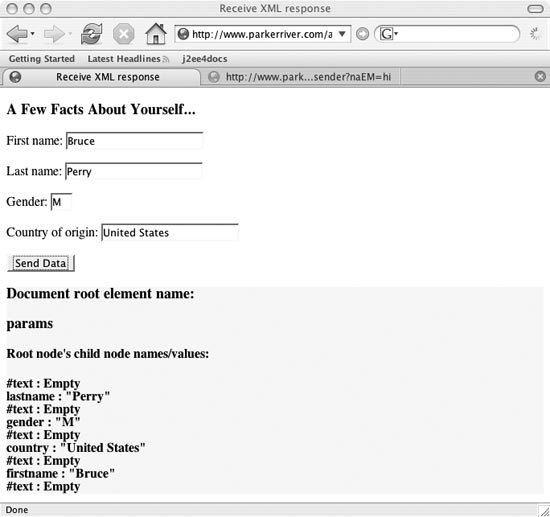

After the code POSTs its data and receives a response, it calls a

method named getDocInfo(), which builds a string that displays some information about

the XML document and its child or subelements:

var doc = request.responseXML; var info = getDocInfo(doc);

The getDocInfo() function

gets a reference to the root XML element (var root =

doc.documentElement;); it then builds a string specifying the name of the root element

and information about any of its child nodes or elements, such as the

child node name and value. The code then feeds this information to the

stylizeDiv() method. The stylizeDiv() method uses the div element at the end of the HTML page to

dynamically display the gathered information:

function stylizeDiv(bdyTxt,div){

//reset div content

div.innerHTML="";

div.style.backgroundColor="yellow";

div.innerHTML=bdyTxt;

}Figure 1-4 shows what the web page looks like after the application receives the XML response.

Tip

The text nodes that the application shows are newline characters in the returned XML.

The core DOM API offered by the browser’s JavaScript implementation provides developers with a powerful tool for programming complex XML return values.

Get Plain Old Strings

Manage weather readings, stock quotes, web page scrapings, or similar non-XML data as plain old strings.

The request object has the perfect property for web

applications that do not have to handle server return values as XML:

request.responseText. This hack asks

the user to choose a stock symbol, and the server returns the stock

price for display. The code handles the return value as a string.

Tip

A variation to this program in the next hack requires the stock prices to be handled as numbers. These are old prices that a server component stores for certain stock symbols, not live quotes that you would obtain from a commercial web service or by HTML scraping. For an example of that mechanism, see “Use XMLHttpRequest to Scrape a Energy Price from a Web Page” [Hack #39].

First, here is the HTML for the web page. It imports JavaScript code from a file named hack9.js:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/hack9.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Choose a stock</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>Stock prices</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit=

"getStockPrice(this.stSymbol.value);return false">

<p>Enter stock symbol: <input type="text" name=

"stSymbol" size="4"><span id="stPrice"></span></p>

<p><button type="submit">Get Stock Price</button></p>

</form>

</body>

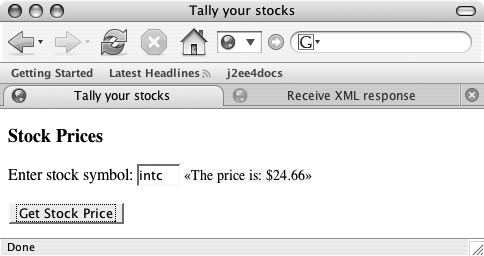

</html>Figure 1-5

shows the web page as displayed in Firefox. The user enters a symbol

such as “GRMN” (case insensitive) and clicks the Get Stock Price button;

the JavaScript then fetches the associated stock price and displays it

within a span element to the right of

the text field.

The function that sets the request process in motion is getStockPrice(). This function takes the value

of the text field named stSymbol and

returns the associated stock price (it uses the request object to talk

to a server component, which fetches the actual stock price). Here is

the JavaScript code:

var request;

var symbol; //will hold the stock symbol

function getStockPrice(sym){

symbol=sym;

if(sym){

var url="http://localhost:8080/parkerriver/s/stocks?symbol="+sym;

httpRequest("GET",url,true);

}

}

//event handler for XMLHttpRequest

function handleResponse(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

/* Grab the result as a string */

var stockPrice = request.responseText;

var info = "«The price is: $"+stockPrice+"»";

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.fontSize="0.9em";

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.

backgroundColor="yellow";

document.getElementById("stPrice").innerHTML=info;

} else {

alert("A problem occurred with communicating between "+

"the XMLHttpRequest object and the server program.");

}

}//end outer if

}

/* See Hack #1 for the httpRequest() code;

it is snipped here for the sake of brevity. */The function getStockPrice()

wraps a call to the function httpRequest(), which is responsible for

setting up the request object. If you have already read through some of

this chapter’s other hacks, you will recognize the handleResponse() function as enclosing much

of the interesting action.

Tip

“Detect Browser

Compatibility with the Request Object” [Hack #1] and “Use Your Own Library for

XMLHttpRequest” [Hack #3] explain the httpRequest() function in more

detail.

If the request is complete (i.e., if request.readyState has a value of 4) and the HTTP response status is 200 (meaning that the request has succeeded),

the code grabs the server response as the request.responseText property value. The code

then uses DOM scripting to display the stock price with some CSS

style-related attributes:

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.fontSize="0.9em";

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.backgroundColor="yellow";

document.getElementById("stPrice").innerHTML =info;The style attributes make the

font size a little bit smaller than the user’s preferred browser font

size and specify yellow as the background color of the text display. The

innerHtml property of the span element is set to the stock price within

double angle brackets.

Receive Data as a Number

Do numerical calculations that depend on the request object’s return value as a number.

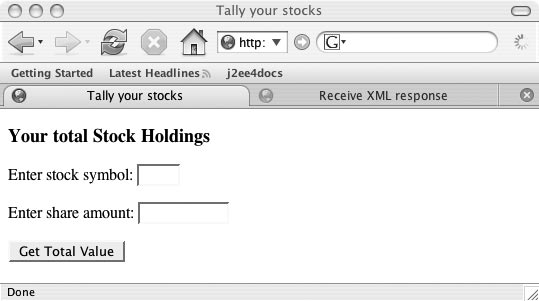

This hack receives a stock quote as a number, then dynamically displays the total value of a stock holding based on the number of shares a user enters. If the server does not send a valid number, the application displays an error message to the user.

The great advantage of Ajax technology is in receiving discrete

values rather than entire web pages from a server. Sometimes, that

discrete information has to be used as a number, rather than as a

string (as discussed in the last

hack) or some other object. JavaScript is usually pretty smart about

converting values to number types without your intervention, but still,

you don’t want your application to multiply an innocent investor’s share

quantity by undefined or some other

weird data the server returns!

This hack checks that the user has entered a proper number for a “number of shares” value. The code also checks the server return value to make sure it is numerically valid. It then dynamically displays the stock price and total value of the shares in the user’s browser.

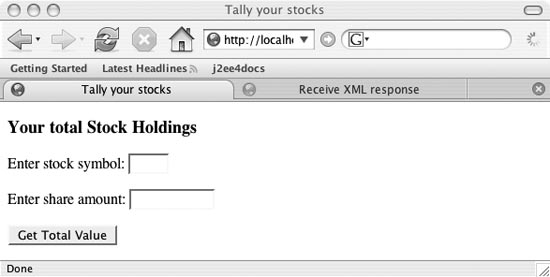

Figure 1-6 shows what the browser form looks like.

The following code shows the HTML for the web page:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="/parkerriver/js/hack4.js">

</script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Tally your stocks</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>Your total Stock Holdings</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit=

"getStockPrice(this.stSymbol.value,this.numShares.value);return false">

<p>Enter stock symbol: <input type="text" name="stSymbol" size="4">

<span id="stPrice"></span></p>

<p>Enter share amount: <input type="text" name="numShares" size="10"></p>

<p><button type="submit">Get Total Value</button></p>

<div id="msgDisplay"></div>

</form>

</body>

</html>When the user clicks the Get Total Value button, this action

triggers the form element’s onsubmit event. The event handler for this

event is the getStockPrice() function. This function takes

the stock symbol and the number of shares as its two parameters. The

return false part of the event-handling code

cancels the browser’s typical submission of the

form values to the URL specified by the form tag’s action attribute.

Number Crunching

Now let’s look at the JavaScript code, which the HTML file imports as part of the hack4.js file:

var request;

var symbol; //will hold the stock symbol

var numberOfShares;

function getStockPrice(sym,shs){

if(sym && shs){

symbol=sym;

numberOfShares=shs;

var url="http://localhost:8080/parkerriver/s/stocks?symbol="+sym;

httpRequest("GET",url,true);

}

}

//event handler for XMLHttpRequest

function handleResponse(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

alert(request.status);

if(request.status == 200){

/* Check if the return value is actually a number.

If so, multiply by the number of shares and display the result */

var stockPrice = request.responseText;

try{

if(isNaN(stockPrice)) { throw new Error(

"The returned price is an invalid number.");}

if(isNaN(numberOfShares)) { throw new Error(

"The share amount is an invalid number.");}

var info = "Total stock value: "+ calcTotal(stockPrice);

displayMsg(document.

getElementById("msgDisplay"),info,"black");

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.fontSize="0.9em";

document.getElementById("stPrice").innerHTML ="price:

"+stockPrice;

} catch (err) {

displayMsg(document.getElementById("msgDisplay"),

"An error occurred: "+

err.message,"red");

}

} else {

alert(

"A problem occurred with communicating between the "+

"XMLHttpRequest object and the server program.");

}

}//end outer if

}

/* See Hack #1 or #2 for the httpRequest() code sample and the associated function

initReq(). They are snipped here for the sake of brevity. */

function calcTotal(price){

return stripExtraNumbers(numberOfShares * price);

}

/* Strip any characters beyond a scale of four characters

past the decimal point, as in 12.3454678 */

function stripExtraNumbers(num){

//check if the number's already okay

//assume a whole number is valid

var n2 = num.toString();

if(n2.indexOf(".") == -1) { return num; }

//if it has numbers after the decimal point,

//limit the number of digits after the decimal point to 4

//we use parseFloat if strings are passed into the method

if(typeof num == "string"){

num = parseFloat(num).toFixed(4);

} else {

num = num.toFixed(4);

}

//strip any extra zeros

return parseFloat(num.toString().replace(/0*$/,""));

}

function displayMsg(div,bdyText,txtColor){

//reset DIV content

div.innerHTML="";

div.style.backgroundColor="yellow";

div.style.color=txtColor;

div.innerHTML=bdyText;

}All the number crunching starts in the call to handleResponse(). First, the code receives

the response as a string, in

var stockPrice =

request.responseText. The code then tests the validity of

the stockPrice variable using a

method that is part of JavaScript’s core API: isNaN(). This is the best way to test

whether a string value in

JavaScript can represent a valid number. For example, isNaN("goodbye") returns true because “goodbye” cannot be converted

to a number. The code also tests the number of shares value with this

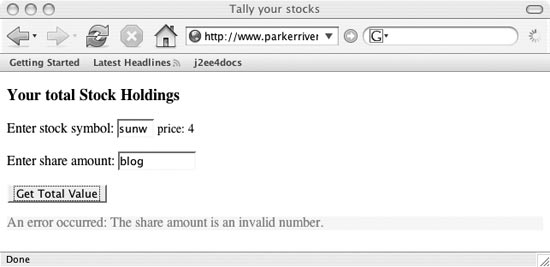

function.

If either method returns true, indicating an invalid number value,

the code throws an exception. This is another way of declaring, “We

can’t use these values; get them out of here!” The web page then

displays an error message to the user.

Tip

Exception handling with Ajax is covered in “Handle Request Object Errors” [Hack #8].

However, we’re not yet finished with our number crunching. The

calcTotal() function then multiplies the

share total by the stock price in order to display the total value to

the user.

To make sure that the numerical display of the value is friendly

enough to the eye (in terms of the U.S. stock exchange), the stripExtraNumbers() function keeps no more

than four characters to the right of the decimal point.

Tip

Even though $10.9876 may look a little weird (stock prices are sometimes displayed with four or more characters to the right of the decimal point), I decided to allow this display for the total share value.

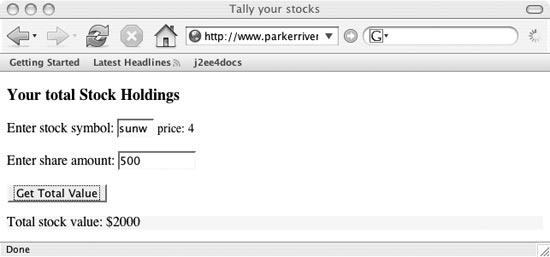

DOM-inating

The code uses Document Object Model programming to

dynamically display new text and values on the page, all without

having to make new server calls and refresh the entire page. The

following bit of code, within the handleResponse() function, calls the

displayMsg() function to show the user the

total share value. The code also dynamically embeds the stock price

just to the right of the text field where the user entered the stock

symbol. All the code does here is get a reference to the div element with id

stPrice, make its font-size style property a little smaller

than the web user’s font setting, and then set the div’s innerHTML property:

displayMsg(document.getElementById("msgDisplay"),info,"black");

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.fontSize="0.9em";

document.getElementById("stPrice").innerHTML ="price: "+stockPrice;The displayMsg() function

is also simple. It has a parameter that represents the font color,

which allows the code to set the font color “red” for error

messages:

function displayMsg(div,bdyText,txtColor){

//reset DIV content

div.innerHTML="";

div.style.backgroundColor="yellow";

div.style.color=txtColor;

div.innerHTML=bdyText;

}Figure 1-7 shows what the page looks like when the user requests a stock value.

Figure 1-8 shows an example error message, in case the user enters values that cannot be used as numbers or the server returns invalid values.

Receive Data in JSON Format

Ajax can receive data in efficient and powerful JavaScript Object Notation.

How would you like to use Ajax and receive data from the server as plain old JavaScript objects? Well, you can, using a format called JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). This hack takes information entered by a web user and initiates a server round trip, which returns the data in JSON syntax for the web page’s use.

JSON is simple and straightforward, which is probably why a lot of developers like it. JSON-formatted data is appropriate for simple objects that are bundles of properties and values. An example is a server program that pulls product information from a database or cache and returns it to a retail web page in JSON format. Data in JSON format is represented by:

The values of each property in the object can be:

Simple strings, such as

"hello"Arrays, such as

[1,2,3,4]Numbers

The values

true,false, ornullOther objects, as in a composition, or an object containing one or more objects

Tip

See http://www.json.org for further details.

This is exactly the format of an Object literal in JavaScript. As an example,

here is what the information requested of the user in “Use the Request Object to POST Data to

the Server” [Hack #2] looks like in JSON format:

{

firstname:"Bruce",

lastname:"Perry",

gender:"M",

country:"USA"

}Magic JSON

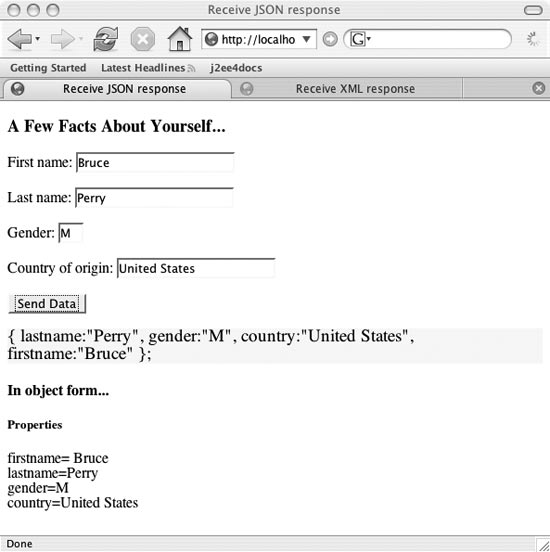

In this section, we’ll use a similar HTML page to the one used

in “Use the Request Object to

POST Data to the Server” [Hack #2], and we’ll ask the user for

the same information; however, this hack uses JavaScript code and Ajax

to handle a JSON return value from the server. Two div elements at the bottom of the HTML page

show the JSON return value from the server and then display the

object’s properties and values in a more friendly fashion.

Here’s the code for the HTML page:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/hack5.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Receive JSON response</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>A Few Facts About Yourself...</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit="sendData();return false">

<p>First name: <input type="text" name="firstname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Last name: <input type="text" name="lastname" size="20"> </p>

<p>Gender: <input type="text" name="gender" size="2"> </p>

<p>Country of origin: <input type="text" name="country" size="20"> </p>

<p><button type="submit">Send Data</button></p>

<div id="json"></div>

<div id="props"></div>

</form>

</body>

</html>Figure 1-9 shows what the web page looks like.

The JavaScript code is imported by the script tag and specified by the file

hack5.js. The JavaScript sends the user’s

entered values to the server; because this was discussed in “Use the Request Object to POST Data

to the Server” [Hack #2] and other hacks, the code is

reproduced here but doesn’t go into great detail.

Warning

Beware of cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks when evaluating any

return values as JavaScript code in this manner. This is a potential

threat for any use of eval() or

the Function-related code

discussed in this hack.

As a countermeasure, the client-side JavaScript can filter and

inspect the return value (e.g., by looking at the XMLHttpRequest responseText property) for the presence of

the expected object property names before the code uses responseText in the eval() function (see http://www.perl.com/pub/a/2002/02/20/css.html).

Here’s the code for this hack. Below, we’ll go over the key parts that handle the return value as a JavaScript object.

var request;

var queryString; //will hold the POSTed data

function sendData(){

setQueryString();

url="http://localhost:8080/parkerriver/s/json";

httpRequest("POST",url,true);

}

//event handler for XMLHttpRequest

function handleJson(){

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

var resp = request.responseText;

var func = new Function("return "+resp);

var objt = func();

var div = document.getElementById("json");

stylizeDiv(resp,div);

div = document.getElementById("props");

div.innerHTML="<h4>In object form...</h4>"+

"<h5>Properties</h5>firstname= "+

objt.firstname +"<br />lastname="+

objt.lastname+ "<br />gender="+

objt.gender+ "<br />country="+

objt.country;

} else {

alert("A problem occurred with communicating between "+

"the XMLHttpRequest object and the server program.");

}

}//end outer if

}

/* Initialize a request object that is already constructed */

function initReq(reqType,url,bool){

/* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */

request.onreadystatechange=handleJson;

request.open(reqType,url,bool);

request.setRequestHeader("Content-Type",

"application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8");

request.send(queryString);

}

/* Wrapper function for constructing a request object.

Parameters:

reqType: The HTTP request type, such as GET or POST.

url: The URL of the server program.

asynch: Whether to send the request asynchronously or not. */

function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch){

//Snipped... See Hack #1 or #2

}

function setQueryString(){

queryString="";

var frm = document.forms[0];

var numberElements = frm.elements.length;

for(var i = 0; i < numberElements; i++){

if(i < numberElements-1){

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value)+"&";

} else {

queryString += frm.elements[i].name+"="+

encodeURIComponent(frm.elements[i].value);

}

}

}

function stylizeDiv(bdyTxt,div){

//reset DIV content

div.innerHTML=" ";

div.style.fontSize="1.2em";

div.style.backgroundColor="yellow";

div.appendChild(document.createTextNode(bdyTxt));

}As in this chapter’s previous hacks, the initReq() function initializes the request

object and sends an HTTP request to the server.

The event-handling function for when the response is ready is

called handleJson(). The response is a

JSON-formatted text string, as opposed to XML or some other text type.

As is, JavaScript interprets this returned text as a string object. Therefore, the code initiates

an opening step before the server’s return value is interpreted as a

JavaScript object literal. (By the

way, in this hack, the server takes the request parameters and

reformats the parameter names and property values into JSON syntax,

prior to sending the reformatted data as its response.)

Tip

Special error-handling code is not included here, because these elements require further explanation and are covered by “Handle Request Object Errors” [Hack #8].

Within the handleJson()

code (highlighted in the previous code sample), the variable resp refers to the HTTP response text, which

JavaScript interprets as a string.

The interesting stuff occurs in the

Function constructor:

var func = new Function("return "+resp);This code creates a new Function object on the fly and stores the

Function in a variable named

func. JavaScript coders might note

that most functions are predefined and declared in code, or created as

function literals. However, in this case we need to define a function

body dynamically using a string,

and the Function constructor

provides the perfect tool.

Tip

Thanks to this site for guidance on this code usage: http://www.jibbering.com/2002/4/httprequest.html.

Another method for converting JSON strings that’s making its way around the Web goes like this:

var resp = request.responseText;var obj = eval( "(" + resp + ")" );You do not have to use the parentheses characters when using

eval() and an array, as in:

var resp = request.responseText;//resp contains something like "[1,2,3,4]"var arrObject = eval(resp);

The next line creates a function that returns an object literal, representing the server return

value. You then call the function and use the returned object to dynamically display server values

on the web page with DOM programming (all without complex object serialization or a page

refresh!):

var objt = func();

var div = document.getElementById("json");

stylizeDiv(resp,div);

div = document.getElementById("props");

div.innerHTML="<h4>In object form...</h4><h5>Properties</h5>firstname= "+

objt.firstname +"<br />lastname="+

objt.lastname+ "<br />gender="+

objt.gender+ "<br />country="+

objt.country;A variable named objt stores the object literal. The values are pulled from

the object with syntax such as

objt.firstname. Figure 1-10 shows

what the web page looks like after it has received a response.

On the Server Side

A Java servlet handles requests for this hack. For those

interested in the server activity, here is the doPost() method for this code:

protected void doPost(HttpServletRequest httpServletRequest,

HttpServletResponse httpServletResponse) throws

ServletException, IOException {

Map valMap = httpServletRequest.getParameterMap();

StringBuffer body = new StringBuffer("{\\n");

if(valMap != null) {

String val=null;

String key = null;

Map.Entry me = null;

Set entries = valMap.entrySet();

int size = entries.size();

int counter=0;

for(Iterator iter= entries.iterator();iter.hasNext();) {

counter++;

me=(Map.Entry) iter.next();

val= ((String[])me.getValue())[0];

key = (String) me.getKey();

if(counter < size) {

body.append(key).append(":\\"").append(val).append("\\",\\n");

} else {

//remove comma for last entry

body.append(key).append(":\\"").append(val).append("\\"\\n");

}

}

}

body.append("}");

AjaxUtil.sendText(httpServletResponse,body.toString());

}The AjaxUtil class sends the

HTTP response with a Content-Type

of text/plain; charset=UTF-8. Some

web sites have discussed using a Content-Type of application/x-json for JSON, but as of this

writing, developers and standards bodies have not yet settled on a

standard relating to this matter.

The AjaxUtil class also sets

the HTTP response header Cache-Control to no-cache, which tells the browser or user

agent not to cache the responses:

response.setHeader("Cache-Control", "no-cache");

Handle Request Object Errors

Design your Ajax application to detect any server errors and provide a friendly user message.

Much of the oomph behind Ajax technology is that it allows JavaScript to connect with a server program without the user intervening. However, JavaScript developers often have no control over the server component itself (which could be a web service or other software designed outside their organizations). Even if your application involves your organization’s server component, you cannot always be sure that the server is behaving normally or even that your users are online at the moment they trigger your request object. You have to make sure that your application recovers in the event that the backend program is unavailable.

This hack traps errors and displays a meaningful error message, in the event that the Ajax application loses server contact.

Problems, Problems...

This hack addresses the following exceptional events, and recommends ways for the application to recover from them:

The web application or server component you are connecting with is temporarily unavailable.

The server your application is connecting with is down, or its URL has changed unbeknownst to you.

The server component you connect with has one or more bugs, and it crashes during your connection (yeech!).

When you call the

open()method with the request object, your code uses a different host address than the address from which the user downloaded the web page. The request object throws an exception in this case when you try to call itsopen()method.

You can use this hack’s exception-handling code in any application. This hack uses the stock calculation code from “Receive Data as a Number” [Hack #6]. We’ll take a look at the code that initializes the request object and the exception-handling mechanism in a moment, but first, here’s the HTML file that imports the JavaScript code from hack6.js:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/hack6.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>Tally your stocks</title>

</head>

<body>

<h3>Your total Stock Holdings</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200" onsubmit=

"getStockPrice(this.stSymbol.value,this.numShares.value);return false">

<p>Enter stock symbol: <input type="text" name="stSymbol" size="4">

<span id="stPrice"></span></p>

<p>Enter share amount: <input type="text" name="numShares" size="10"></p>

<p><button type="submit">Get Total Value</button></p>

<div id="msgDisplay"></div>

</form>

</body>

</html>When users load this file into their browsers, they see the screen shown in Figure 1-11.

The code we are interested in can trap exceptions involving

unavailable applications, backend servers that are down, backend

server bugs, and erroneous URLs. The

handleResponse() function is the event

handler for managing the server response, as in request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse.

The following code uses a nested try/catch/finally statement to deal with

invalid numbers handled by the application, as discussed in “Receive Data as a Number” [Hack

#6].

function handleResponse(){

var statusMsg="";

try{

if(request.readyState == 4){

if(request.status == 200){

/* Check if the return value is actually a number.

If so, multiply by the number

of shares and display the result */

var stockPrice = request.responseText;

try{

if(isNaN(stockPrice)) { throw new Error(

"The returned price is an invalid number.");}

if(isNaN(numberOfShares)) { throw new Error(

"The share amount is an invalid number.");}

var info = "Total stock value: $"+

calcTotal(stockPrice);

displayMsg(document.

getElementById("msgDisplay"),info,"black");

document.getElementById("stPrice").style.fontSize="0.

9em";

document.getElementById("stPrice").innerHTML ="price: "+

stockPrice;

} catch (err) {

displayMsg(document.getElementById("msgDisplay"),

"An error occurred: "+

err.message,"red");

}

} else {

//request.status is 503 if the application isn't available;

//500 if the application has a bug

alert(

"A problem occurred with communicating between the "

"XMLHttpRequest object and the server program. "+

"Please try again very soon");

}

}//end outer if

} catch (err) {

alert("It does not appear that the server "+

"is available for this application. Please "+

"try again very soon. \\nError: "+err.message);

}

}Now, let’s take a look at how this code handles the different types of exceptions previously enumerated.

Floored Server

A try block traps any exceptions thrown within

its curly braces ( {}). If the code throws an exception, this

mechanism executes the code within the associated catch block. The inner try block, which is designed to manage

exceptions thrown in the event of invalid numeric values, is explained

in “Receive Data as a Number”

[Hack #6].

So, what happens if the server host is completely down, even

though the URL your application uses is otherwise correct? In this

case, the code’s attempt to access the request.status property throws an exception

because the request object never receives the expected response header

from the server and the status

property is not associated with any data.

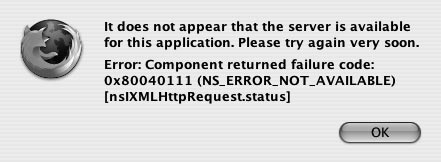

As a result, the code displays the alert window defined in the outer catch block. Figure 1-12 depicts

what the alert window looks like

after this type of error.

The code displays a user message, as well as the more techie error message associated with the exception. You can leave out that part of the message if you desire; it is mainly useful for debugging purposes.

Tip

The err variable in the

code is a reference to the JavaScript Error object. The message property of this object (as in

err.message) is the actual error

message, a string generated by

the JavaScript engine.

If you do not include this try/catch/finally mechanism, the user sees

just an alert window containing the

indecipherable error message generated by JavaScript. After dismissing

this window (or leaving the computer in frustration), the user has no

way of knowing what state the application is in.

Backend Application Out to Lunch

Sometimes the application server or host is running

okay, but the server component you want to connect with is out of

service. In this case, the value of the

request.status property is 503 (“Service

Unavailable”). Because the status

property holds a value other than 200, this hack’s code executes the

expression contained within the else statement block:

} else {

//request.status is 503 if the application isn't available;

// 500 if the application has a bug

alert(

"A problem occurred with communicating between the "

"XMLHttpRequest object and the server program. "+

"Please try again very soon");

}In other words, the user sees an alert window explaining the application’s

status. This alert also appears if

the server component has a bug and crashes. This event typically (such

as with the Tomcat servlet container) results in a 500 response status

code (“Internal Server Error”), so response.status evaluates to 500 instead of 200 (“Okay”). In addition, any 404 response

codes involving a static or dynamic component that the server cannot

find at the URL you provided are captured with this try statement.

Tip

The try/catch/finally

statement is available only with JavaScript engines of JS Version

1.4 or later. The optional finally statement block follows the

catch block. The code enclosed by

finally{...} executes regardless

of whether or not an exception is thrown.

Whoops, Wrong URL

What if the URL that your Ajax application uses in the

request.open() method is wrong or

has changed? In this case, the

request.open() call throws the

exception, so this is where you have to position your try/catch/finally statement. The code at the

top of the next example constructs a request object [Hack #1]. The following

function definition, initReq(),

catches the exception just described:

function httpRequest(reqType,url,asynch){

//Mozilla-based browsers

if(window.XMLHttpRequest){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else if (window.ActiveXObject){

request=new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

if (! request){

request=new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

}

}

//the request could still be null if neither ActiveXObject

//initialization succeeded

if(request){

initReq(reqType,url,asynch);

} else {

alert("Your browser does not permit the use of all "+

"of this application's features!");

}

}

/* Initialize a request object that is already constructed */

function initReq(reqType,url,bool){

try{

/* Specify the function that will handle the HTTP response */

request.onreadystatechange=handleResponse;

request.open(reqType,url,bool);

request.send(null);

} catch (err) {

alert(

"The application cannot contact the server at the moment."+

" Please try again in a few seconds.");

}

}Another variation of this error is when the URL you use with the

request.open() method includes a

different host than the host from which the user downloaded the web

page. For example, say the user downloads the web page from

http://www.myorg.com/app, but the URL you use for

open() is

http://www.yourorg.com. This type of error is

also caught by the code’s try/catch/finally statement.

Tip

You can also optionally abort or cancel the request in the

catch block with request.abort(). For more information,

see “Set a Time Limit for the

HTTP Request” [Hack #70] and its discussion of setting a

timeout for the request and aborting it in the event that the

request is not completed within a certain period.

Dig into the HTTP Response

Display the values of various HTTP response headers in addition to or in lieu of a typical server return value.

An HTTP response header is descriptive information,

laid out by the HTTP 1.1 protocol, that web servers send requestors

along with the actual web page or data. If you have already coded with

the XMLHttpRequest object (discussed

at the beginning of this chapter), you know that the request.status property equates to an HTTP

response status code sent from the server. This is an important value to

check before your page does anything cool with the HTTP response.

Tip

Status values can include 200

(the request went through okay), 404 (the requested file or URL path was not

found), or 500 (internal server

error).

However, you might want to see some of the other response headers

associated with the request, such as the type of web server software

associated with the response (the Server response header) or the content type of

the response (the Content-Type

header). This hack requests the user to enter a URL in a text field.

When the user tabs out of or clicks outside of the text field, the

browser displays various HTTP response headers. As usual with Ajax, this

happens without a page refresh.

Tip

This request object method returns only a subset of the

available response headers, including Content-Type, Date, Server, and Content-Length.

Here is the HTML page code:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/hack7.js"></script>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>view response headers</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/parkerriver/css/hacks.css" />

</head>

<body onload="document.forms[0].url.value=urlFragment">

<h3>Find out the HTTP response headers when you "GET" a Web page</h3>

<form action="javascript:void%200">

<p>Enter a URL:

<input type="text" name="url" size="20" onblur="getAllHeaders(this.value)">

<span class="message">::press tab when finished editing the

field::</span></p>

<div id="msgDisplay"></div>

</form>

</body>

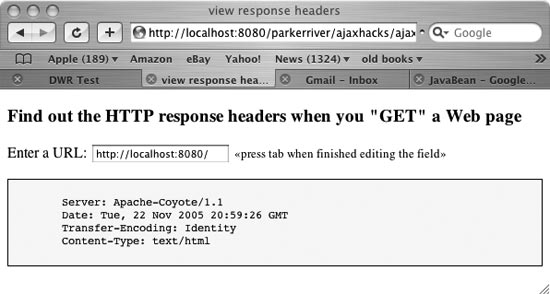

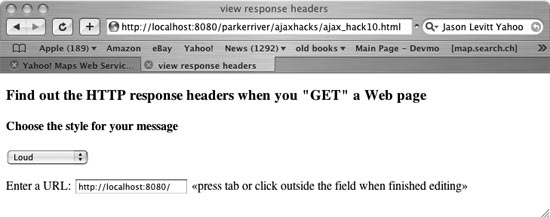

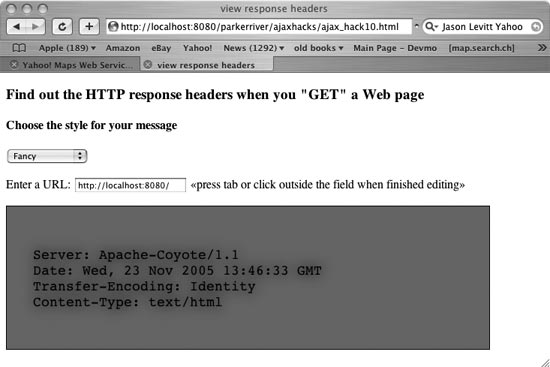

</html>Figure 1-13 shows the page in the Safari browser.

The application prefills the text field with a partial URL (e.g., http:// localhost:8080/) for the user to complete, because the request object cannot send a request to a different host from the host that uploaded the web page to the user. In other words, the partially completed URL provides a hint to the user that the application can only send a request to that specified host.

When the user completes the URL and then presses the Tab key or

clicks outside the text field, the text field’s onblur event handler is triggered. The event

handler is defined as a function named

getAllHeaders(), which passes the URL the user

has entered to the request object. The request object then sends a

request to the URL and returns the available response headers to the web

page.

The following code is from the

hack7.js file that the page imports. After

showing this code, I explain the parts that deal with displaying the

server’s response headers. “Detect

Browser Compatibility with the Request Object” [Hack #1] explains

how to initialize and open an HTTP connection with the request object,

otherwise known as XMLHttpRequest.

“Handle Request Object Errors”