2. Input to the Common Gateway Interface

2.1 Introduction

When a CGI program is called, the information that is made available to it can be roughly broken into three groups:

- Information about the client, server, and user

- Form data that the user supplied

- Additional pathname information

Most information about the client, server, or user is placed in CGI environment variables. Form data is either incorporated into an environment variable, or is included in the “body” of the request. And extra path information is placed in environment variables.

See a trend here? Obviously, CGI environment variables are crucial to accessing input to a CGI program. In this chapter, we will first look at a number of simple CGI programs under UNIX that display and manipulate input. We will show some examples that use environment variables to perform some useful functions, followed by examples that show how to process HTML form input. Then we will focus our attention on processing this information on different platforms.

2.2 Using Environment Variables

Much of the most crucial information needed by CGI applications is made available via UNIX environment variables. Programs can access this information as they would any environment variable (e.g., via the %ENV associative array in Perl).

This section concentrates on showing examples of some of the more typical uses of environment variables in CGI programs. First, however, Table 2.1 shows a full list of environment variables available for CGI.

Table 2.1: List of CGI Environment Variables

| Environment Variable | Description |

| GATEWAY_INTERFACE | The revision of the Common Gateway Interface that the server uses. |

| SERVER_NAME | The server's hostname or IP address. |

| SERVER_SOFTWARE | The name and version of the server software that is answering the client request. |

| SERVER_PROTOCOL | The name and revision of the information protocol the request came in with. |

| SERVER_PORT | The port number of the host on which the server is running. |

| REQUEST_METHOD | The method with which the information request was issued. |

| PATH_INFO | Extra path information passed to a CGI program. |

| PATH_TRANSLATED | The translated version of the path given by the variable PATH_INFO. |

| SCRIPT_NAME | The virtual path (e.g., /cgi-bin/program.pl) of the script being executed. |

| DOCUMENT_ROOT | The directory from which Web documents are served. |

| QUERY_STRING | The query information passed to the program. It is appended to the URL with a “?”. |

| REMOTE_HOST | The remote hostname of the user making the request. |

| REMOTE_ADDR | The remote IP address of the user making the request. |

| AUTH_TYPE | The authentication method used to validate a user. |

| REMOTE_USER | The authenticated name of the user. |

| REMOTE_IDENT | The user making the request. This variable will only be set if NCSA IdentityCheck flag is enabled, and the client machine supports the RFC 931 identification scheme (ident daemon). |

| CONTENT_TYPE | The MIME type of the query data, such as “text/html”. |

| CONTENT_LENGTH | The length of the data (in bytes or the number of characters) passed to the CGI program through standard input. |

| HTTP_FROM | The email address of the user making the request. Most browsers do not support this variable. |

| HTTP_ACCEPT | A list of the MIME types that the client can accept. |

| HTTP_USER_AGENT | The browser the client is using to issue the request. |

| HTTP_REFERER | The URL of the document that the client points to before accessing the CGI program. |

We'll use examples to demonstrate how these variables are typically used within a CGI program.

About This Server

Let's start with a simple program that displays various information about the server, such as the CGI and HTTP revisions used and the name of the server software.

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Content-type: text/html", "\n\n";

print "<HTML>", "\n";

print "<HEAD><TITLE>About this Server</TITLE></HEAD>", "\n";

print "<BODY><H1>About this Server</H1>", "\n";

print "<HR><PRE>";

print "Server Name: ", $ENV{'SERVER_NAME'}, "<BR>", "\n";

print "Running on Port: ", $ENV{'SERVER_PORT'}, "<BR>", "\n";

print "Server Software: ", $ENV{'SERVER_SOFTWARE'}, "<BR>", "\n";

print "Server Protocol: ", $ENV{'SERVER_PROTOCOL'}, "<BR>", "\n";

print "CGI Revision: ", $ENV{'GATEWAY_INTERFACE'}, "<BR>", "\n";

print "<HR></PRE>", "\n";

print "</BODY></HTML>", "\n";

exit (0);

Let's go through this program step by step. The first line is very important. It instructs the server to use the Perl interpreter located in the /usr/local/bin directory to execute the CGI program. Without this line, the server won't know how to run the program, and will display an error stating that it cannot execute the program.

Once the CGI script is running, the first thing it needs to generate is a valid HTTP header, ending with a blank line. The header generally contains a content type, also known as a MIME type. In this case, the content type of the data that follows is text/html.

After the MIME content type is output, we can go ahead and display output in HTML. We send the information directly to standard output, which is read and processed by the server, and then sent to the client for display. Five environment variables are output, consisting of the server name (the IP name or address of the machine where the server is running), the port the server is running on, the server software, and the HTTP and CGI revisions. In Perl, you can access the environment variables through the %ENV associative array, keyed by name.

A typical output of this program might look like this:

<HTML> <HEAD><TITLE>About this Server</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY><H1>About this Server</H1> <HR><PRE> Server Name: bu.edu Running on Port: 80 Server Software: NCSA/1.4.2 Server Protocol: HTTP/1.0 CGI Revision: CGI/1.1 <HR></PRE> </BODY></HTML>

Check the Client Browser

Now, let's look at a slightly more complicated example. One of the more useful items that the server passes to the CGI program is the client (or browser) name. We can put this information to good use by checking the browser type, and then displaying either a text or graphic document.

Different Web browsers support different HTML tags and different types of information. If your CGI program generates an inline image, you need to be sensitive that some browsers support <IMG> extensions that others don't, some browsers support JPEG images as well as GIF images, and some browsers (notably, Lynx and the old www client) don't support images at all. Using the HTTP_USER_AGENT environment variable, you can determine which browser is being used, and with that information you can fine-tune your CGI program to generate output that is optimized for that browser.

Let's build a short program that delivers a different document depending on whether the browser supports graphics. First, identify the browsers that you know don't support graphics. Then get the name of the browser from the HTTP_USER_AGENT variable:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

$nongraphic_browsers = 'Lynx|CERN-LineMode';

$client_browser = $ENV{'HTTP_USER_AGENT'};

The variable $nongraphic_browsers contains a list of the browsers that don't support graphics. Each browser is separated by the “|” character, which represents alternation in the regular expression we use later in the program. In this instance, there are only two browsers listed, Lynx and www. (“CERN-LineMode” is the string the www browser uses to identify itself.)

The HTTP_USER_AGENT environment variable contains the name of the browser. All environment variables that start with HTTP represent information that is sent by the client. The server adds the prefix and sends this data with the other information to the CGI program.

Now identify the files that you intend to return depending on whether the browser supports graphics:

$graphic_document = "full_graphics.html"; $text_document = "text_only.html";

The variables $graphic_document and $text_document contain the names of the two documents that we will use.

The next thing to do is simply to check if the browser name is included in the list of non-graphic browsers.

if ($client_browser =~ /$nongraphic_browsers/) {

$html_document = $text_document;

} else {

$html_document = $graphic_document;

}

The conditional checks whether the client browser is one that we know does not support graphics. If it is, the variable $html_document will contain the name of the text-only version of the HTML file. Otherwise, it will contain the name of the version of the HTML document that contains graphics.

Finally, print the partial header and open the file. (We need to get the document root from the DOCUMENT_ROOT variable and prepend it to the filename, so the Perl program can locate the document in the file system.)

print "Content-type: text/html", "\n\n";

$document_root = $ENV{'DOCUMENT_ROOT'};

$html_document = join ("/", $document_root, $html_document);

if (open (HTML, "<" . $html_document)) {

while (<HTML>) {

print;

}

close (HTML);

} else {

print "Oops! There is a problem with the configuration on this system!", "\n";

print "Please inform the Webmaster of the problem. Thanks!", "\n";

}

exit (0);

If the filename stored in $html_document can be opened for reading (as specified by the “<” character), the while loop iterates through the file and displays it. The open command creates a handle, HTML, which is then used to access the file. During the while loop, as Perl reads a line from the HTML file handle, it places that line in its default variable $_. The print statement without any arguments displays the value stored in $_. After the entire file is displayed, it is closed. If the file cannot be opened, an error message is output.

Restricting Access for Specified Domains

Suppose you have a set of HTML documents: one for users in your IP domain (e.g., bu.edu), and another one for users outside of your domain. Why would anyone want to do this, you may ask? Say you have a document containing internal company phone numbers, meeting schedules, and other company information. You certainly don't want everyone on the Internet to see this document. So you need to set up some type of security to keep your documents away from prying eyes.

You can configure most servers to restrict access to your documents according to what domain the user connects from. For example, under the NCSA server, you can list the domains which you want to allow or deny access to certain directories by editing the access.conf configuration file. However, you can also control domain-based access in a CGI script. The advantage of using a CGI script is that you don't have to turn away other domains, just send them different documents. Let's look at a CGI program that performs pseudo authentication:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl $host_address = 'bu\.edu'; $ip_address = '128\.197';

These two variables hold the IP domain name and address that are considered local. In other words, users in this domain can access the internal information. The period is “escaped” in both of these variables (by placing a “\” before the character), because the variables will be interpolated in a regular expression later in this program. The “.” character has a special significance in a regular expression; it is used to match any character other than a newline.

$remote_address = $ENV{'REMOTE_ADDR'};

$remote_host = $ENV{'REMOTE_HOST'};

The environment variable REMOTE_ADDR returns the IP numerical address for the remote user, while REMOTE_HOST contains the IP alphanumeric name for the remote user. There are times when REMOTE_HOST will not return the name, but only the address (if the DNS server does not have an entry for the domain). In such a case, you can use the following snippet of code to convert an IP address to its corresponding name:

@subnet_numbers = split (/\./, $remote_address);

$packed_address = pack ("C4", @subnet_numbers);

($remote_host) = gethostbyaddr ($packed_address, 2);

Don't worry about this code yet. We will discuss functions like these in Chapter 9, Gateways, Databases, and Search/Index Utilities. Now, let's continue with the rest of this program.

$local_users = "internal_info.html";

$outside_users = "general.html";

if (($remote_host =~ /\.$host_address$/) && ($remote_address =~ /^$ip_address/)) {

$html_document = $local_users;

} else {

$html_document = $outside_users;

}

The remote host is examined to see if it ends with the domain name, as specified by the $host_address variable, and the remote address is checked to make sure it starts with the domain address stored in $ip_address. Depending on the outcome of the conditional, the $html_document variable is set accordingly.

print "Content-type: text/html", "\n\n";

$document_root = $ENV{'DOCUMENT_ROOT'};

$html_document = join ("/", $document_root, $html_document);

if (open (HTML, "<" . $html_document)) {

while (<HTML>) {

print;

}

close (HTML);

} else {

print "Oops! There is a problem with the configuration on this system!", "\n";

print "Please inform the Webmaster of the problem. Thanks!", "\n";

}

exit (0);

The specified document is opened and the information stored within it is displayed.

User Authentication and Identification

In addition to domain-based security, most HTTP servers also support a more complicated method of security, known as user authentication. When configured for user authentication, specified files or directories are set up to allow access only by certain users. A user attempting to open the URLs associated with these files is prompted for a name and password.

The user name and password (which, incidentally, need have no relation to the user's real user name and password on any system) is checked by the server, and if legitimate, the user is allowed access. In addition to allowing the user access to the protected file, the server also maintains the user's name and passes it to any subsequent CGI programs that are called. The server passes the user name in the REMOTE_USER environment variable.

A CGI script can therefore use server authentication information to identify users.[1] This isn't what user authentication was meant for, but if the information is available, it can come in mighty handy. Here is a snippet of code that illustrates what you can do with the REMOTE_USER environment variable:

$remote_user = $ENV{'REMOTE_USER'};

if ($remote_user eq "jack") {

print "Welcome Jack, how is Jack Manufacturing doing these days?", "\n";

} elsif ($remote_user eq "bob") {

print "Hey Bob, how's the wife doing? I heard she was sick.", "\n";

}

.

.

.

Server authentication does not provide complete security: Since the user name and password are sent unencrypted over the network, it's possible for a “snoop” to look at this data. For that reason, it's a bad idea to use your real login name and password for server authentication.

Where Did You Come From?

Companies who provide services on the Web often want to know from what server (or document) the remote users came. For example, say you visit the server located at http://www.cgi.edu, and then from there you go to http://www.flowers.com/. A CGI program on www.flowers.com can actually determine that you were previously at www.cgi.edu.

How is this useful? For advertising, of course. If a company determines that 90% of all users that visit them come from a certain server, then they can perhaps work something out financially with the webmaster at that server to provide advertising. Also, if your site moves or the content at your site changes dramatically, you can help avoid frustration among your visitors by informing the webmasters at the sites referring to yours to change their links. Here is a simple program that displays this “referral” information:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

$remote_address = $ENV{'REMOTE_ADDR'};

$referral_address = $ENV{'HTTP_REFERER'};

print "Hello user from $remote_address!", "\n";

print "The last site you visited was: $referral_address. Am I genius or what?", "\n";

exit (0);

The environment variable HTTP_REFERER, which is passed to the server by the client, contains the last site the user visited before accessing the current server.

Now for the caveats. There are three important things you need to remember before using the HTTP_REFERER variable:

- First, not all browsers set this variable.

- Second, if a user accesses your server first, right at startup, this variable will not be set.

- Third, if someone accesses your site via a bookmark or just by typing in the URL, the referring document is meaningless. So if you are keeping some sort of count to determine where users are coming from, it won't be totally accurate.

2.3 Accessing Form Input

Finally, let's get to form input. We mentioned forms briefly in Chapter 1, The Common Gateway Interface, and we'll cover them in more detail in Chapter 4, Forms and CGI. But here, we just want to introduce you to the basic concepts behind forms.

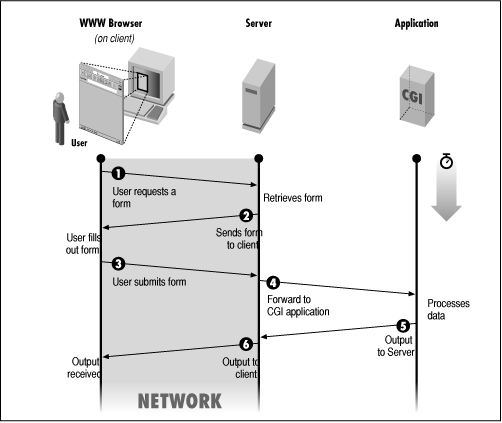

As we described in Chapter 1, forms provide a way to get input from users and supply it to a CGI program, as shown in Figure 2.1. The Web browser allows the user to select or type in information, and then sends it to the server when the Submit button is pressed. In this chapter, we'll talk a little about how the CGI program accesses the form input.

Figure 2.1: Form interaction with CGI

Query Strings

One way to send form data to a CGI program is by appending the form information to the URL, after a question mark. You may have seen URLs like the following:

http://some.machine/cgi-bin/name.pl?fortune

Up to the question mark (?), the URL should look familiar. It is merely a CGI script being called, by the name name.pl.

What's new here is the part after the “?”. The information after the “?” character is known as a query string. When the server is passed a URL with a query string, it calls the CGI program identified in the first part of the URL (before the “?”) and then stores the part after the “?” in the environment variable QUERY_STRING. The following is a CGI program called name.pl that uses query information to execute one of three possible UNIX commands.

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

$query_string = $ENV{'QUERY_STRING'};

if ($query_string eq "fortune") {

print `/usr/local/bin/fortune`;

} elsif ($query_string eq "finger") {

print `/usr/ucb/finger`;

} else {

print `/usr/local/bin/date`;

}

exit (0);

You can execute this script as either:

http://some.machine/cgi-bin/name.pl?fortune http://some.machine/cgi-bin/name.pl?finger

or

http://some.machine/cgi-bin/name.pl

and you will get different output. The CGI program executes the appropriate system command (using backtics) and the results are sent to standard output. In Perl, you can use backtics to capture the output from a system command.

NOTE:

You should always be very careful when executing any type of system commands in CGI applications, because of possible security problems. You should never do something like this:

print `$query_string`;

NOTE:

The danger is that a diabolical user can enter a dangerous system command, such as:

rm -fr /

NOTE:

which can delete everything on your system.

Nor should you expose any system data, such as a list of system processes, to the outside world.

A Simple Form

Although the previous example will work, the following example is a more realistic illustration of how forms work with CGI. Instead of supplying the information directly as part of the URL, we'll use a form to solicit it from the user.

(Don't worry about the HTML tags needed to create the form; they are covered in detail in Chapter 4, Forms and CGI.)

<HTML> <HEAD><TITLE>Simple Form!</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY> <H1>Simple Form!</H1> <HR> <FORM ACTION="/cgi-bin/unix.pl" METHOD="GET"> Command: <INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="command" SIZE=40> <P> <INPUT TYPE="submit" VALUE="Submit Form!"> <INPUT TYPE="reset" VALUE="Clear Form"> </FORM> <HR> </BODY> </HTML>

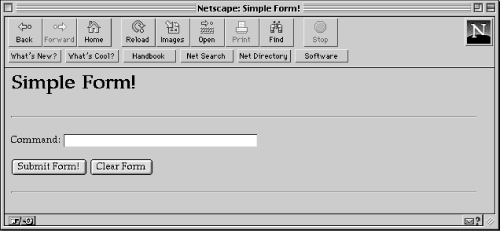

Since this is HTML, the appearance of the form depends on what browser is being used. Figure 2.2 shows what the form looks like in Netscape.

Figure 2.2: Simple form in Netscape

This form consists of one text field titled “Command:” and two buttons. The Submit Form! button is used to send the information in the form to the CGI program specified by the ACTION attribute. The Clear Form button clears the information in the field.

The METHOD=GET attribute to the <FORM> tag in part determines how the data is passed to the server. We'll talk more about different methods soon, but for now, we'll use the default method, GET. Now, assuming that the user enters “fortune” into the text field, when the Submit Form! button is pressed the browser sends the following request to the server:

GET /cgi-bin/unix.pl?command=fortune HTTP/1.0 . . (header information) .

The server executes the script called unix.pl in the cgi-bin directory, and places the string “command=fortune” into the QUERY_STRING environment variable. Think of this as assigning the variable “command” (specified by the NAME attribute to the <INPUT> tag) with the string supplied by the user, “fortune”.

command=fortune

Let's go through the simple unix.pl CGI program that handles this form:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

$query_string = $ENV{'QUERY_STRING'};

($field_name, $command) = split (/=/, $query_string);

After printing the content type (text/plain in this case, since the UNIX programs are unlikely to produce HTML output) and getting the query string from the %ENV array, we use the split function to separate the query string on the “=” character into two parts, with the first part before the equal sign in $field_name, and the second part in $command. In this case, $field_name will contain “command” and $command will contain “fortune.” Now, we're ready to execute the UNIX command:

if ($command eq "fortune") {

print `/usr/local/bin/fortune`;

} elsif ($command eq "finger") {

print `/usr/ucb/finger`;

} else {

print `/usr/local/bin/date`;

}

exit (0);

Since we used the GET method, all the form data is included in the URL. So we can directly access this program without the form, by using the following URL:

http://some.machine/cgi-bin/unix.pl?command=fortune

It will work exactly as if you had filled out the form and submitted it.

The GET and POST Methods

In the previous example, we used the GET method to process the form. However, there is another method we can use, called POST. Using the POST method, the server sends the data as an input stream to the program. That is, if in the previous example the <FORM> tag had read:

<FORM ACTION="unix.pl" METHOD="POST">

the following request would be sent to the server:

POST /cgi-bin/unix.pl HTTP/1.0 . . (header information) . Content-length: 15 command=fortune

The version of unix.pl that handles the form with POST data follows. First, since the server passes information to this program as an input stream, it sets the environment variable CONTENT_LENGTH to the size of the data in number of bytes (or characters). We can use this to read exactly that much data from standard input.

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

$size_of_form_information = $ENV{'CONTENT_LENGTH'};

Second, we read the number of bytes, specified by $size_of_form_information, from standard input into the variable $form_info.

read (STDIN, $form_info, $size_of_form_information);

Now we can split the $form_info variable into a $field_name and $command, as we did in the GET version of this example. As with the GET version, $field_name will contain “command,” and $command will contain “fortune” (or whatever the user typed in the text field). The rest of the example remains unchanged:

($field_name, $command) = split (/=/, $form_info);

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

if ($command eq "fortune") {

print `/usr/local/bin/fortune`;

} elsif ($command eq "finger") {

print `/usr/ucb/finger`;

} else {

print `/usr/local/bin/date`;

}

exit (0);

Since it's the form that determines whether the GET or POST method is used, the CGI programmer can't control which method the program will be called by. So scripts are often written to support both methods. The following example will work with both methods:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

$request_method = $ENV{'REQUEST_METHOD'};

if ($request_method eq "GET") {

$form_info = $ENV{'QUERY_STRING'};

} else {

$size_of_form_information = $ENV{'CONTENT_LENGTH'};

read (STDIN, $form_info, $size_of_form_information);

}

($field_name, $command) = split (/=/, $form_info);

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

if ($command eq "fortune") {

print `/usr/local/bin/fortune`;

} elsif ($command eq "finger") {

print `/usr/ucb/finger`;

} else {

print `/usr/local/bin/date`;

}

exit (0);

The environment variable REQUEST_METHOD contains the request method used by the form. In this example, the only new thing we did was check the request method and then assign the $form_info variable as needed.

Encoded Data

So far, we've shown an example for retrieving very simple form information. However, form information can get complicated. Since under the GET method the form information is sent as part of the URL, there can't be any spaces or other special characters that are not allowed in URLs. Therefore, some special encoding is used. We'll talk more about this in Chapter 4, Forms and CGI, but for now we'll show a very simple example. First the HTML needed to create a form:

<HTML> <HEAD><TITLE>When's your birthday?</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY> <H1>When's your birthday?</H1> <HR> <FORM ACTION="/cgi-bin/birthday.pl" METHOD="POST"> Birthday (in the form of mm/dd/yy): <INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="birthday" SIZE=40> <P> <INPUT TYPE="submit" VALUE="Submit Form!"> <INPUT TYPE="reset" VALUE="Clear Form"> </FORM> <HR> </BODY> </HTML>

When the user submits the form, the client issues the following request to the server (assuming the user entered 11/05/73):

POST /cgi-bin/birthday.pl HTTP/1.0 . . (information) . Content-length: 21 birthday=11%2F05%2F73

In the encoded form, certain characters, such as spaces and other character symbols, are replaced by their hexadecimal equivalents. In this example, our program needs to “decode” this data, by converting the “%2F” to “/”.

Here is the CGI program-birthday.pl-that handles this form:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

$size_of_form_information = $ENV{'CONTENT_LENGTH'};

read (STDIN, $form_info, $size_of_form_information);

The following complicated-looking regular expression is used to “decode” the data (see Chapter 4, Forms and CGI for a comprehensive explanation of how this works).

$form_info =~ s/%([\dA-Fa-f][\dA-Fa-f])/pack ("C", hex ($1))/eg;

In the case of this example, it will turn “%2F” into “/”. The rest of the program should be easy to follow:

($field_name, $birthday) = split (/=/, $form_info); print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n"; print "Hey, your birthday is on: $birthday. That's what you told me, right?", "\n"; exit (0);

2.4 Extra Path Information

Besides passing query information to a CGI script, you can also pass additional data, known as extra path information, as part of the URL. The extra path information depends on the server knowing where the name of the program ends, and understanding that anything following the program name is “extra.” Here is how you would call a script with extra path information:

http://some.machine/cgi-bin/display.pl/cgi/cgi_doc.txt

Since the server knows that display.pl is the name of the program, the string “/cgi/cgi_doc.txt” is stored in the environment variable PATH_INFO. Meanwhile, the variable PATH_TRANSLATED is also set, which maps the information stored in PATH_INFO to the document root directory (e.g., /usr/local/etc/httpd/public/cgi/cgi-doc.txt).

Here is a CGI script--display.pl--that can be used to display text files located in the document root hierarchy:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

$plaintext_file = $ENV{'PATH_TRANSLATED'};

print "Content-type: text/plain", "\n\n";

if ($plaintext_file =~ /\.\./) {

print "Sorry! You have entered invalid characters in the filename.", "\n";

print "Please check your specification and try again.", "\n";

} else {

if (open (FILE, "<" . $plaintext_file)) {

while (<FILE>) {

print;

}

close (FILE);

} else {

print "Sorry! The file you specified cannot be read!", "\n";

}

}

exit (0);

In this example, we perform a simple security check. We make sure that the user didn't pass path information containing “..”. This is so that the user cannot access files located outside of the document root directory.

Instead of using the PATH_TRANSLATED environment variable, you can use a combination of PATH_INFO and DOCUMENT_ROOT, which contains the physical path to the document root directory. The variable PATH_TRANSLATED is equal to the following statement:

$path_translated = join ("/", $ENV{'DOCUMENT_ROOT'}, $ENV{'PATH_INFO'};

However, the DOCUMENT_ROOT variable is not set by all servers, and so it is much safer and easier to use PATH_TRANSLATED.

2.5 Other Languages Under UNIX

You now know the basics of how to handle and manipulate the CGI input in Perl. If you haven't guessed by now, this book concentrates primarily on examples in Perl, since Perl is relatively easy to follow, runs on all three major platforms, and also happens to be the most popular language for CGI. However, CGI programs can be written in many other languages, so before we continue, let's see how we can accomplish similar things in some other languages, such as C/C++, the C Shell, and Tcl.

C/C++

Here is a CGI program written in C (but that will also compile under C++) that parses the HTTP_USER_AGENT environment variable and outputs a message, depending on the type of browser:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void main (void)

{

char *http_user_agent;

printf ("Content-type: text/plain\n\n");

http_user_agent = getenv ("HTTP_USER_AGENT");

if (http_user_agent == NULL) {

printf ("Oops! Your browser failed to set the HTTP_USER_AGENT ");

printf ("environment variable!\n");

} else if (!strncmp (http_user_agent, "Mosaic", 6)) {

printf ("I guess you are sticking with the original, huh?\n");

} else if (!strncmp (http_user_agent, "Mozilla", 7)) {

printf ("Well, you are not alone. A majority of the people are ");

printf ("using Netscape Navigator!\n");

} else if (!strncmp (http_user_agent, "Lynx", 4)) {

printf ("Lynx is great, but go get yourself a graphic browser!\n");

} else {

printf ("I see you are using the %s browser.\n", http_user_agent);

printf ("I don't think it's as famous as Netscape, Mosaic or Lynx!\n");

}

exit (0);

}

The getenv function returns the value of the environment variable, which we store in the http_user_agent variable (it's actually a pointer to a string, but don't worry about this terminology). Then, we compare the value in this variable to some of the common browser names with the strncmp function. This function searches the http_user_agent variable for the specified substring up to a certain position within the entire string.

You might wonder why we're performing a partial search. The reason is that generally, the value returned by the HTTP_USER_AGENT environment variable looks something like this:

Lynx/2.4 libwww/2.14

In this case, we need to search only the first four characters for the string “Lynx” in order to determine that the browser being used is Lynx. If there is a match, the strncmp function returns a value of zero, and we display the appropriate message.

C Shell

The C Shell has some serious limitations and therefore is not recommended for any type of CGI applications. In fact, UNIX guru Tom Christiansen has written a FAQ titled “Csh Programming Considered Harmful” detailing the C Shell's problems. Here is a small excerpt from the document:

The csh is seductive because the conditionals are more C-like, so the path of least resistance is chosen and a csh script is written. Sadly, this is a lost cause, and the programmer seldom even realizes it, even when they find that many simple things they wish to do range from cumbersome to impossible in the csh.

However, for completeness sake, here is a simple shell script that is identical to the first unix.pl Perl program discussed earlier:

#!/bin/csh

echo "Content-type: text/plain"

echo ""

if ($?QUERY_STRING) then

set command = `echo $QUERY_STRING | awk 'BEGIN {FS = "="} { print $2 }'`

if ($command == "fortune") then

/usr/local/bin/fortune

else if ($command == "finger") then

/usr/ucb/finger

else

/usr/local/bin/date

endif

else

/usr/local/bin/date

endif

The C Shell does not have any inherent functions or operators to manipulate string information. So we have no choice but to use another UNIX utility, such as awk, to split the query string and return the data on the right side of the equal sign. Depending on the input from the user, one of several UNIX utilities is called to output some information.

You may notice that the variable QUERY_STRING is exposed to the shell. Generally, this is very dangerous because users can embed shell metacharacters. However, in this case, the variable substitution is done after the “ command is parsed into separate commands. If things happened in the reverse order, we could potentially have a major headache!

Tcl

The following Tcl program uses an environment variable that we haven't yet discussed up to this point. The HTTP_ACCEPT variable contains a list of all of the MIME content types that a browser can accept and handle. A typical value returned by this variable might look like this:

application/postscript, image/gif, image/jpeg, text/plain, text/html

You can use this information to return different types of data from your CGI document to the client. The program below parses this accept list and outputs each MIME type on a different line:

#!/usr/local/bin/tclsh

puts "Content-type: text/plain\n"

set http_accept $env(HTTP_ACCEPT)

set browser $env(HTTP_USER_AGENT)

puts "Here is a list of the MIME types that the client, which"

puts "happens to be $browser, can accept:\n"

set mime_types [split $http_accept ,]

foreach type $mime_types {

puts "- $type"

}

exit 0

As in Perl, the split command splits a string on a specified delimiter, placing all of the resulting substrings in an array. In this case, the mime_types array contains each MIME type from the accept list. Once that's done, the foreach loop iterates through the array, displaying each element.

2.6 Other Languages Under Microsoft Windows

On Microsoft Windows, your mileage varies according to which Web server you use. The freely available 16-bit server for Windows 3.1, Bob Denny's winhttpd, supports a CGI interface for Perl programs, but it also supports a Windows CGI interface that allows you to write CGI programs in languages like Visual Basic, Delphi, and Visual C++.

Under Windows NT and Windows 95, available servers are WebSite by O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. (developed by Denny as a 32-bit commercial product), NetSite by Netscape, Purveyor by Process Software, and the Internet Server Solution from Microsoft (not yet released as of this writing, but imminent and not easily ignored). There is also another freely available server ( EMWACS), although it is not considered as robust as the commercial products.

All platforms support CGI development in Perl. In addition, WebSite, Netscape, and Microsoft all include Windows CGI interfaces. However, the CGI implementations are all slightly different.

Visual Basic

Visual Basic is perfect for developing CGI applications because it supports numerous features for accessing data in the Windows environment. This includes OLE, DDE, Sockets, and ODBC. ODBC, or Open Database Connectivity, allows you to access a variety of relational and non-relational databases. The actual implementation of the Windows CGI interface determines how CGI variables are read from a Visual Basic program. This simple example uses the WebSite 1.0 server, which depends on a CGI.BAS module that sets up some global variables representing the CGI variables.

Sub CGI_Main ()

Send ("Content-type: text/plain")

Send ("")

Send ("Server Name")

Send ("")

Send ("The server name is: " & CGI_ServerName)

End Sub

The module function Main in CGI.BAS calls the user-written CGI_Main function when executing the CGI program. The CGI_ServerName variable contains the name of the server. As we said, your mileage will vary according to which Windows-based server you use.

Perl for Windows NT

As I mentioned earlier, Perl has been ported to Windows NT as well as to many other platforms, including DOS and Windows 3.1. This makes CGI programming much easier on these platforms, because we have access to the powerful pattern-matching abilities and to various extensions to such utilities as databases and graphics packages.

2.7 Other Languages on Macintosh Servers

The two commonly used HTTP servers for the Macintosh are WebSTAR and MacHTTP, both of which are nearly identical in their functionality. These servers use AppleEvents to communicate with external applications, such as CGI programs. The language of choice for CGI programming on the Macintosh is AppleScript.

AppleScript

Though AppleScript does not have very intuitive functions for pattern matching, there exist several CGI extensions, called osax (Open Scripting Architecture eXtended), that make CGI programming very easy. Here is a simple example of an AppleScript CGI:

set crlf to (ASCII character 13) & (ASCII character 10)

set http_header to "HTTP/1.0 200 OK" & crlf & -

"Server: WebSTAR/1.0 ID/ACGI" & crlf & -

"MIME-Version: 1.0" & crlf & "Content-type: text/html" & crlf & crlf

on `event WWWsdoc' path_args -

given `class kfor':http_search_args, `class post':post_args, `class meth':method,

`class addr':client_address, `class user':username, `class pass':password, `class frmu':from_user, `class svnm':server_name, `class svpt':server_port,

`class scnm':script_name, `class ctyp':content_type, `class refr':referer,

`class Agnt':user_agent, `class Kact':action, `class Kapt':action_path,

`class Kcip':client_ip, `class Kfrq':full_request

set virtual_document to http_header & -

"<H1>Server Software</H1><BR><HR>" & crlf -

"The server that is responding to your request is: " & server_name & crlf -

"<BR>" & crlf

return virtual_document

end `event WWW sdoc'

Although the mechanics of this code might look different from those of previous examples, this AppleScript program functions in exactly the same way. First, the HTTP header that we intend to output is stored in the http_header variable. Both MacHTTP and WebSTAR servers require CGI programs to output a complete header. Second, the on construct sets up a handler for the “sdoc” AppleEvent, which consists of all the “environment” information and form data. This event is sent to the CGI program by the server when the client issues a request. Finally, the header and other data are returned for display on the client.

MacPerl

Yes, Perl has also been ported to the Macintosh! This will allow you to develop your CGI applications in much the same way as you would under the UNIX operating system. However, you need to obtain the MacHTTP CGI Script Extension. This extension allows you to use the associative array %ENV to access the various environment variables in MacPerl.

2.8 Examining Environment Variables

What would the chapter be without a program that displays some of the commonly used environment variables? Here it is:

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

%list = ('SERVER_SOFTWARE', 'The server software is: ',

'SERVER_NAME', 'The server hostname, DNS alias, or IP address is: ',

'GATEWAY_INTERFACE', 'The CGI specification revision is: ',

'SERVER_PROTOCOL', 'The name and revision of info protocol is: ',

'SERVER_PORT', 'The port number for the server is: ',

'REQUEST_METHOD', 'The info request method is: ',

'PATH_INFO', 'The extra path info is: ',

'PATH_TRANSLATED', 'The translated PATH_INFO is: ',

'DOCUMENT_ROOT', 'The server document root directory is: ',

'SCRIPT_NAME', 'The script name is: ',

'QUERY_STRING', 'The query string is (FORM GET): ',

'REMOTE_HOST', 'The hostname making the request is: ',

'REMOTE_ADDR', 'The IP address of the remote host is: ',

'AUTH_TYPE', 'The authentication method is: ',

'REMOTE_USER', 'The authenticated user is: ',

'REMOTE_IDENT', 'The remote user is (RFC 931): ',

'CONTENT_TYPE', 'The content type of the data is (POST, PUT): ',

'CONTENT_LENGTH', 'The length of the content is: ',

'HTTP_ACCEPT', 'The MIME types that the client will accept are: ',

'HTTP_USER_AGENT', 'The browser of the client is: ',

'HTTP_REFERER', 'The URL of the referer is: ');

print "Content-type: text/html","\n\n";

print "<HTML>", "\n";

print "<HEAD><TITLE>List of Environment Variables</TITLE></HEAD>", "\n";

print "<BODY>", "\n";

print "<H1>", "CGI Environment Variables", "</H1>", "<HR>", "\n";

while ( ($env_var, $info) = each %list ) {

print $info, "<B>", $ENV{$env_var}, "</B>", "<BR>","\n";

}

print "<HR>", "\n";

print "</BODY>", "</HTML>", "\n";

exit (0);

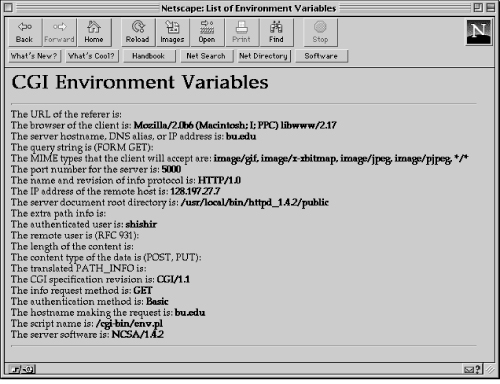

The associative array contains each environment variable and its description. The while loop iterates through the array one variable at a time with the each command. Figure 2.3 shows what the output will look in a browser window.

Figure 2.3: Output of example program

[1] The HTTP_FROM environment variable also carries information that can be used to identify a user-generally, the user's email address. However, this variable depends on the browser to make it available, and few browsers do, so HTTP_FROM is of limited use.

Get CGI Programming on the World Wide Web now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.