Our society has a polarized, contradictory view of how the mind works—either we think we’re careful, rational people, or we’re just emotional wrecks that are lucky to get through the day alive. Sometimes we even hold both views at the same time—we consider ourselves to be rational, but those in opposing political parties or in different departments at work are blinded by their emotions.[9]

Well, the truth is that both are absolutely true—and they are true at the same time, in every single one of us. That fact is essential to understanding how to design products that change behavior.

We have two modes of thinking in the brain—one is deliberative and the other is intuitive. Psychologists have a well-developed understanding of how they work, called dual process theory.[10] Our intuitive mode (or “emotional” mode; it’s also called “System 1”), is blazingly fast and automatic, but we’re generally not conscious of its inner workings. It uses our past experiences and a set of simple rules of thumb to almost immediately give us an intuitive evaluation of a situation—an evaluation we feel through our emotions and through sensations around our bodies like a “gut feeling” ([ref41]). It’s generally quite effective in familiar situations, where our past experiences are relevant, and does less well in unfamiliar situations.

Our deliberative mode (aka our “conscious” mode or “System 2”) is slow, focused, self-aware and what most of us consider “thinking.” We can rationally analyze our way through unfamiliar simulations, and handle complex problems with System 2. Unfortunately, System 2 is woefully limited in how much information it can handle at a time (we struggle holding more than seven numbers in short-term memory at once! [[ref132]]), and thus relies on System 1 for much of the real work of thinking. These two systems can work independently of each other, in parallel, and can disagree with one another—like when we’re troubled by the sense that, despite our careful thinking, “something is just wrong” with a decision we’ve taken.[11]

The distinction between deliberative and intuitive thinking is just one of the many findings that researchers have discovered about how the mind works. In fact, there are literally hundreds of such lessons, many of which describe quirky mechanisms that lead us to behave in unexpected ways.[12] Each one describes a piece of how the mind works, and often, how that piece can push individuals toward one action or another. To give you an idea of their breadth, here are just some of the mechanisms that start with the letter “A”:[13]

- Ambiguity effect

We’re intuitively uncomfortable with actions in which the potential effects have unknown probabilities. This makes us avoid otherwise preferred options when uncertainty is added ([ref57]).

- Anchoring

We automatically use an initial reference point (anchor) as basis for estimates, even if the estimate is wrong. For example, the initial listing prices for houses, even if completely invalid, strongly affect how much buyers (and real estate agents) think the house is worth ([ref143])!

- Attentional bias

We pay attention to particular cues in our environment based on our internal state. For example, people who are addicted to a drug are extra sensitive to cues related to their addiction. They effectively see things that relate to the drug more often than everyone else, whether they want to or not ([ref63]).

- Availability cascade

Incorrect (and correct) ideas can become increasingly believed and widespread because of (a) repetition by well-meaning people who don’t want to appear wrong, and (b) manipulation from interested parties. [ref112] cite the example of the Love Canal toxic waste scare in New York—which, from expert accounts, was vastly overblown and was later discredited.

- Availability heuristic

We estimate the likelihood of events based on how easy they are to remember. For example, people incorrectly believe that the names of famous people to be more common than normal names ([ref176]).

Various authors provide lists of mechanisms, and ways that those mechanisms can affect our behavior.[14] What’s lacking are good guidelines on how to use these scattered bits and pieces of research in actual products.

Ironically, one of the phenomena that researchers have studied is choice overload ([ref94]; [ref159]). In short, we are drawn to big lists like these, but once we actually try to use them and pick out the “best” or the “most useful” one, we are paralyzed and unable to choose! This occurs with everything from 401(k) plans ([ref95]) to buying jam at a supermarket ([ref96]). We’re just not good at handling choices among lots of complex options. We need fewer options, or a better way to organize them that doesn’t overwhelm us.

This book provides one way to organize the research literature, focusing on the most important lessons for practical product development. The distinction between System 1 and System 2 is a good place to start, so let’s build on that.

At least, we’re not choosing consciously. Most of our daily behavior is governed by our intuitive mode. We’re acting on habit (learned patterns of behavior), on gut instinct (blazingly fast evaluations of a situation based on our past experiences), or on simple rules of thumb (cognitive shortcuts or heuristics built into our mental machinery).[15] Researchers estimate that roughly half of our daily lives are spent executing habits and other intuitive behaviors, and not consciously thinking about what we’re doing (see [ref185]; [ref44]). Our conscious minds usually only become engaged when we’re in a novel situation, or when we intentionally direct our attention to a task.[16]

Unfortunately, our conscious minds believe that they are in charge all the time, even when they aren’t. [ref86] and [ref89] build on the Buddha’s metaphor of a rider and an elephant to explain this idea: the elephant is our immensely powerful but uncritical, intuitive self. The rider is our conscious self, trying to direct the elephant where to go. The rider thinks it’s always in charge, but it’s the elephant doing the work; if the elephant disagrees with the rider, the elephant usually wins.

There are fascinating studies of people whose left and right brains have been surgically separated and can’t (physically) talk to one another. The left side makes up convincing but completely fabricated stories about what the right side is doing ([ref77]). That’s the rider standing on top of an out-of-control elephant crying out that everything is under control![17] Or, more precisely, crying out that every action that the elephant takes is absolutely what the rider wanted him to do—and the rider actually believes it.

Even though we’re not necessarily choosing what we do, we’re always thinking—even when we’re watching TV or daydreaming. The point is that what we’re doing is sometimes quite different. We might be walking to the office, but we’re actually thinking about all of the stuff we need to do when we get there. The rider is deeply engaged in preparing for the future tasks, and the elephant is doing the work of walking. In order for behavior change to occur, we need to work with both the rider and elephant ([ref89]).

In each part of this section, I include some basic Lessons for Behavioral Products. These are top-level comments, and they are only the beginning—the next few chapters build upon these lessons to think strategically about behavior change, and undertake the design process itself.

Lessons for Behavioral Products

If you design a product to appeal to someone’s conscious, rational decision-making process, you might educate the rational mind, but not actually affect behavior (because it is often intuitive or automatic). Be very clear about the type of behavior you are trying to encourage—a conscious choice or an intuitive response.

We are constantly learning, and our experiences teach us whether something is worthwhile or not—that’s a key part of how we decide what to do at each moment of our lives. Our deliberative mind can carefully analyze experiences and find complex relationships. However, to a large extent, our intuitive responses are grounded in simple associations between things that we’ve experienced in the past. Like an association between a certain subtle perfume and romance, or between a stormy sky and impending rain.[18]

We build these associations constantly in everyday life, and they guide our actions. We learn, for example, that greasy pizzas are strongly associated with tasting good and satisfying hunger—and rice cakes are not. When we’re hungry and confronted with a pizza, our behavior (eating quickly and with great gusto) isn’t a conscious deliberation about the merits of pizza as a nutritional source. Instead, it’s based on the fact that we’ve eaten it before, and we have a positive association for it. The origins of those associations are often invisible once formed (you “just like” pizza), but something in our past experience actually formed them.

Importantly, our intuitive mind learns, and responds, even without our conscious awareness. Participants in a famous study were given four biased decks of cards—some that would win them money, and some that would cause them to lose. When they started the game, they didn’t know that the decks were biased. As they played the game, though, people’s bodies started showing signs of physical “stress” when their conscious minds were about to use a money-losing deck. The stress was an automatic response that occurred because the intuitive mind realized something was wrong—long before the conscious mind realized anything was amiss ([ref16]).[19]

And, once formed, these associations have a life of their own. Our intuitive minds sometimes use them well beyond their original context—we apply them to “similar” situations and experiences even if they aren’t really justified. For example, when someone sees something new, like a new product, he will rapidly and automatically judge it based on the associations he’s built up for similar things. He may have no idea why he reacted the way we did; the answer is buried in his web of learned associations.

Lessons for Behavioral Products

The first time that users try out your application, they immediately judge it based on their prior experiences and associations. You don’t have time to convince them logically; the judgment is made in an instant. Instead, you must proactively gain insight into their prior associations to avoid land mines and find positive hooks that help people change their own behavior. That’s one role of user research.

We use the term “habit” loosely in everyday speech to mean all sorts of things, but a concrete way to think about them is this: a habit is a repeated behavior that’s triggered by cues in our environment. It’s automatic—the action occurs outside of conscious control, and we may not even be aware of it happening.[20] Habits save our minds work; we effectively outsource control over our behavior to cues in the environment ([ref184]). That keeps our conscious minds free for other, more important things, where conscious thought really is required.

Habits arise in one of two ways ([ref184]).[21] First, we can build habits through simple repetition: whenever you see X (a cue), you do Y (a routine). Over time, your brain builds a strong association between the cue and the routine, and doesn’t need to think about what to do when the cue occurs—it just acts. For example, whenever you wake up in the morning (cue), you get out of bed at the same spot (routine). Rarely do you find yourself lying in bed, awake, agonizing over which exact part of the bed you should exit by. That’s how habits work—they are so common, and so deeply ingrained in our lives, that we rarely even notice them.

Sometimes, there is also a third element, in addition to a cue and routine: a reward, something good that happens at the end of the routine. The reward pulls us forward—it gives us a reason to repeat the behavior. It might be something inherently pleasant, like good food, or the completion of a goal we’ve set for ourselves, like putting away all of the dishes ([ref146]). For example, whenever you walk by the café and smell coffee (cue), you walk into the shop, buy a double mocha espresso with cream (routine), and feel chocolate-caffeine goodness (reward). We sometimes notice the big habits—like getting coffee—but other, less obvious habits with rewards (checking our email and receiving the random reward of getting an interesting message) may not be noticed.

Once the habit forms, the reward itself doesn’t directly drive our behavior; the habit is automatic and outside of conscious control. However, the mind can “remember” previous rewards in subtle ways; intuitively wanting (or “craving”) them.[22] In fact, the mind can continue wanting a reward that it will never receive again, and may not even enjoy when it does happen ([ref18])![23] I’ve encountered that strange situation myself—long after I formed the habit of eating certain potato chips, I still habitually eat them even though I don’t enjoy them and they actually make me sick. This isn’t to say that rewards aren’t important after the habit forms—they can push us to consciously repeat the habitual action and can make them even more resistant to change.

The same characteristics that make habits hard to root out can be immensely useful. Thinking of it another way, once “good” habits are formed, they provide the most resilient and sustainable way to maintain a new behavior. Charles Duhigg, in The Power of Habit (Random House, 2012), gives a great example. In the early 1900s, advertising man Claude C. Hopkins moved American society from being one in which very few people brushed their teeth to a majority brushing their teeth in the span of only 10 years. He did it by helping Americans form the habit of brushing:[24]

He taught people a cue—feeling for tooth film, the somewhat slimy, off-white stuff that naturally coats our teeth (apparently, it’s actually harmless in itself).

When people felt tooth film, the response was a routine—brushing their teeth (using Pepsodent, in this case).

The reward was a minty tingle in their mouths—something they felt immediately after brushing their teeth.

Over time, the habit (feel film, brush teeth) formed, strengthened by the reward at the end. And, so did a craving—wanting to feel the cool tingling sensation that Pepsodent caused in their mouths that people associated with having clean, beautiful teeth (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. Pepsodent advertisement from 1950, highlighting the cue for the habit of brushing teeth: tooth film (courtesy of Vintage-Adventures.com)

Stepping back from Duhigg’s example, let’s look again at the three pieces of a reward-driven habit.

The cue is something that tells us to act now. The cue is a clear and unambiguous signal in the environment (like the smell of coffee) or in the person’s body (like hunger). BJ Fogg and Jason Hreha categorize the two ways that they work on behavior into “cue behaviors” and “cycle behaviors” ([ref71]): based on whether the cue is something else that happens and tells you it’s time to act (brushing teeth after eating breakfast) or the cue occurs on a schedule, like at a specific time of day (preparing to go home at 5 p.m. on a weekday).

The routine can be something simple (hear phone ring, answer it) or complex (smell coffee, turn, enter Starbucks, buy coffee, drink it), as long as the scenario in which the behavior occurs is consistent. Where conscious thought is not required (i.e., consistency allows repetition of a previous action without making new decisions), the behavior can be turned into a habit.

The reward can occur every time—like drinking our favorite brand of coffee—or on a more complex “reward schedule.” A reward schedule is the frequency and variability with which a reward occurs each time the behavior occurs. For example, when we pull the arm of (or press the button on) a slot machine, we are randomly rewarded: sometimes we win, sometimes we don’t. Our brains love random rewards. In terms of timing, rewards that occur immediately after the routine are best—they help strengthen the association between cue and routine.

Researchers are actively studying exactly how rewards function, but one of the likely scenarios goes like this: when these three elements are combined, over time, the cue becomes associated with the reward.[25] When we see the cue, we anticipate the reward, and it tempts us to act out the routine to get it. [ref58] has a great phrase for this process: the desire engine. The process takes time, however—varying by person and situation from a few weeks to many months ([ref114]). And again, the desire for the reward can continue long after the reward no longer exists ([ref18]).

Lessons for Behavioral Products

We’re hardwired to build habits—they save our minds work. It’s difficult to overcome existing habits, but we can intentionally create new habits or change existing ones. Once formed, they are resilient. To build them: identify a specific, unambiguous cue, a stable routine, and, ideally, a reward that occurs immediately after the person takes action.

How our intuitive minds react to a situation isn’t predetermined—it isn’t even predetermined how a single person will react, given full knowledge of prior experience, personality, and other traits. The particular mindset we’re in at the moment of action matters immensely.

We have multiple frames of reference, or mindsets,[26] for interpreting and responding to the world, which shape how we act. You can think of these mindsets as facets of our selves, which are built up in different contexts. We often have distinct mindsets for when we’re at work, when we’re home with our family, and when we’re joking with friends. In each of these contexts, we have different behavioral routines as well. For example, we’d respond differently to someone making fun of us in each of these different contexts. We’d also respond very differently to someone asking us to exercise more in each of these contexts.

We always have an active mindset, shaping our choices. That mindset is usually appropriate to the situation we’re in, helping us make sense of environment. However, our mindsets aren’t as fixed and clear cut as we might think—they can be accidentally (or even intentionally) activated based on small cues in our environment. These cues “prime” us to act in a way that is appropriate for that frame of reference. The following is a famous study about what happens when we’re primed to think about stereotypes.

Researchers divided a set of Asian American women into three groups, each of whom were asked a set of questions about their lives, and then subsequently took a math test. The group that received questions relating to race later answered 54% of the math questions correctly; the group that received questions relating to gender later answered only 42% correctly, and those with generic questions were in between, with 49% correct ([ref163]).

In the United States, the common stereotype of women is of bad performance in math, and the common stereotype of Asian Americans is of good performance. Merely being prompted to think about these stereotypes led participants to respond accordingly.[27]

Another example I love comes from a related body of research, on how we build up internal stories or “self-concepts” (also known as self-narratives) about who we are. These self-concepts guide our future behavior: when we’re not sure what to do, we implicitly ask ourselves, “Is this something that fits with whom I am?” They help us interpret the world by focusing our attention and making sense of ambiguous information. We also have multiple self-concepts that become active based on cues in our environment. This particular study changed how students saw themselves:

Randomly selected students who were given a positive interpretation of their early problems in college came to see themselves as capable and performed better on tests than their randomly selected fellows ([ref188]).

With respect to behavior change, you can think of activating or “priming” a particular mindset as a way to change behavior in the short term, and building a supporting self-concept as a way to change it in the long term.

Lessons for Behavioral Products

It is especially important to understand the mindset that individuals are in, as it shapes how they respond to your application. These different facets of self can be selectively activated, and shape our behavior in different contexts. Similarly, if a product can change how a person sees herself (i.e., her self-concept), it can have profound impacts on long-term behavior.

Our minds avoid work whenever possible. Habits and other intuitive reactions are some of the ways of avoiding conscious work. Another way that our minds avoid work, even when we’re consciously thinking something through, is by using rules of thumb or “heuristics.” Heuristics are shortcuts that save our minds effort; they work well in most situations, but occasionally lead us astray ([ref137]; [ref101]).

For example, we employ a “scarcity heuristic”: things that are difficult to obtain are often seen as more valuable than things that aren’t. It’s a very good rule of thumb to go by: platinum is rare and valuable. Dirt isn’t. But sometimes it causes us to make bad decisions, and can be intentionally manipulated. When retailers mark something as “limited time only” or “only five left!” often it’s just a ruse to make us think the item is more valuable. The scarcity heuristic, and indeed most mental heuristics, are examples of a simple shortcut that our minds take: instead of solving the problem at hand, we find an easier problem to solve.[28]

When our mind is confronted with hard problems it can’t immediately solve, it often substitutes a different, easier problem, solves that, and acts like it was the original one! There are a slew of humorous examples in the research literature; one of my favorites is the following:

A group of randomly selected German students were asked first whether they were generally happy, then asked how many dates they had had in the last month. There was no relationship (pun intended) between the two answers.

Another group of randomly selected German students were asked the exact same questions, in reverse order. Suddenly, they judged how happy they were based on the number of dates they’d had!

Remembering how happy you’ve generally been is tough. When you’ve just been asked how many dates you’ve had, it’s easy for the mind to subtly substitute that answer for the harder question (Strack et al. 1998).[29]

Another less humorous example occurs in our everyday life—in how we judge people based on how they look. Holding other things the same—like competency—we vote for politicians according to how attractive the candidates are, their gender, and their race ([ref144]). Our intuitive minds have a hard time processing the complex set of positions and competencies of candidates. So, we use a shortcut: does the person look like us? Are they attractive? Unfortunately, this phenomenon has been well documented in corporate job interviews and salaries as well. Physical beauty does pay (e.g., [ref87]).

Lessons for Behavioral Products

When you ask users questions, they may not answer the question you think. In many cases, they’ll answer a simple quick version of your question. This undermines some of the answers we get from surveys (especially), and it reminds us that we should not take responses too seriously when we ask people whether they will commit to changing their own behavior. Also, if you have a sense of the simple shortcuts people are using, you can target those shortcuts directly. In the preceding example, if you have pictures of people in your app to make it feel more human, ensure the people are attractive and look similar to the users.

One of the most important and common ways that our minds save work is by looking at what other people are doing. If we don’t know what to do, for example, we:

Judge the value of a product or action by whether other people seem to like it—it’s called social proof. That’s why TV shows use canned laughter—we know it’s fake, but it still makes us laugh more ([ref28]).[30]

Judge the value of a product or action by whether “experts” recommend it—even without knowing if they were paid to recommend it! That’s why we hear “9 out of 10 experts recommend” so darned often; it actually works ([ref174]).

Judge whether we should take an action based on whether we perceive the action is common in our social group—via the many flavors of social conformity ([ref33]).[31]

There are multiple processes going on underneath these socially determined behaviors and judgments, and their impacts are widespread. Peer influence, for example, has been studied in countless domains, from voting ([ref78]) to diet and obesity ([ref32]). But at a high level, the lesson is the same—if you want to guess what people will do, look at what others around them are already doing. Usually, we follow what we believe others we trust or others like us are doing. Sometimes we try to explicitly avoid what they are doing. But either way, we’re reacting to our perception of what others around us are doing.

A frequent, if somewhat depressing, topic for researchers is just how limited our minds really are. Yes, there are numerous lines of research on the mind’s many constraints. Not only do we avoid work, we really don’t have the mental horsepower to tackle certain difficult problems head-on, due to the following limitations:

- Memory

George Miller famously studied how limited our immediate memory is—we can generally hold seven (plus or minus two) numbers or other chunks of information in our heads at one time ([ref132]).

- Attention

Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons’s studies showed how limited our attention is: how we can literally fail to notice a big gorilla in the middle of our visual field. They had people watch a basketball game, and count the number of times the ball was passed in a certain way. During the game, the gorilla guy walked right into the middle of the game, beat his chest, and walked on (see [ref27] for a summary). Half of the participants in the study (and many subsequent ones) failed to notice such “obvious” things because they were looking for something else.

- Willpower and mental energy

Roy Baumeister has shown, in gory detail, how our willpower is fundamentally limited, and varies from moment to moment in startling ways ([ref180]; [ref14]). Our ability to concentrate, perform well on mentally challenging tasks, and to resist temptation are all linked to how “tired” our brains are—how much work we’ve recently been asked to do, and how recently we’ve eaten or rested. Researchers have found, for example, that the proportion of inmates granted parole by Israeli judges varies roughly from 65% down to 0% based on how long judges had been working since a break ([ref42]). Our ideal of an impartial judicial system is sadly at odds with our basic human frailties.

When we’re tired, and our willpower is drained, we increasingly rely on our intuitive processing. We tend to go with the status quo (hence the Israeli judges not granting parole). Each choice we make, and especially each temptation we resist, temporarily tires us. For product design, there’s a special lesson—not only do we need to consider how much willpower people have coming into our apps, but we need to think about how our products, and the choices and temptations they present, sap our users of willpower. It’s not all bad news, however—willpower is a skill that people can build up, and something that our products can invest in ([ref14]).[32]

- Decision making

Another line of research shows the limitations of our decision-making processes, at least compared with strategies that would find us the “optimal” answer. When we pick a movie from Netflix or Amazon Instant Video to watch, we don’t read the reviews for every single movie in their catalogs, nor could we. We don’t have the mental power to handle all of that information, nor the time. We “satisfice” ([ref164]), or are satisfied with the first movie that looks sufficiently interesting to watch.[33] Instead of optimizing, we go with the first option we find that is good enough.

Lessons for Behavioral Products

Your users have busy lives and limited mental resources to devote to your product. You can’t assume they have a lot of available attention, willpower, or memory. Build your interfaces to respect our limitations as people, and try to take into account the other demands on the user’s brain.

Whole bodies of research in psychology and behavioral economics are devoted to the lesson that simple, seemingly trivial stuff affects behavior. It affects behavior for some of the reasons previously mentioned—because something in the environment activates a different facet of our selves, or because our minds are trying to avoid work and take the easy option. But there are six other really blazingly obvious things that are worth drawing out, because we too often forget them when developing software:

- Easier really is better

The easier something is to do (i.e., the less mental and physical effort required from the perspective of the user), the more likely the user is to do it. Psychologists study these as “channel factors,” behavioral economists talk about using “nudges” to overcome the small frictions blocking action, and BJ Fogg argues strongly for simplicity—but the lesson is the same. We like to have some challenge in our lives, but we still (usually) take the easy route, all else being equal.

- Familiar really is better

We’re just more comfortable with things we’ve seen before and actions that we’ve taken before. Again, there are lots of reasons—because of the “mere exposure effect” (we like stuff we’ve seen before—[ref189]; [ref21]), or because we’ve built up skill and a sense of self-efficacy (a belief in our ability to successfully tackle the task)—but the lesson is the same. We take the familiar route, all else being equal.

- Beauty really is better

We’re more comfortable with things (including products) that are easy on the eyes, shall we say. In part, it’s because of the “halo effect” ([ref138])—if we really like one aspect of something, we tend to like it overall. In part, it’s because our minds fundamentally mix the ease of viewing, the ease of remembering, and the ease of using something with the value we ascribe to it ([ref160]).[34] Either way, we like stuff that looks good. Not avant garde and incomprehensible, but good.

- Rewarding experiences really do make us want to come back

Our routines are often built around the expectation of a reward we’ve received in the past. Our intuitive responses, based on prior experiences, guide us to avoid things that are like previous bad experiences and toward things like previous good experiences. And, when we think consciously, we clearly weigh the costs and benefits of action. Either way, conscious or not, we like rewarding experiences (i.e., you must have a good product that provides value to the user).

- We really don’t want to fail

We avoid activity that we think we’ll be unsuccessful at. If we think we’ll fail, we foresee two problems—we won’t get the reward for completing the action, and we’ll feel stupid (or be judged harshly by our peers, fail to meet our commitments, etc.). So, another obvious point that bears repeating: don’t make people fail (frequently), or even make them expect that they’ll fail. A challenging experience can be good, but failure is bad.

- We do urgent things first

If your toddler is about to touch a hot stove, and the college savings account you’ve set up for him is underfunded, which one will you act on first? Urgency matters. It’s so obvious that we often forget about it when we build our products—we assume that people have nothing else going on in their lives.

There are always exceptions, and that’s why we test out products in the field to see what is working and what isn’t. But these are six useful rules of thumb.

Lessons for Behavioral Products

Don’t forget the basics. Yes, there’s a huge amount of research literature. The previous sections highlight nonobvious lessons from that literature. But there’s no point if you have a product that is needlessly hard to use, foreign, ugly, painful, lacking urgency, and makes users feel like failures. We all know this, and yes, there’s research to back it up, too.

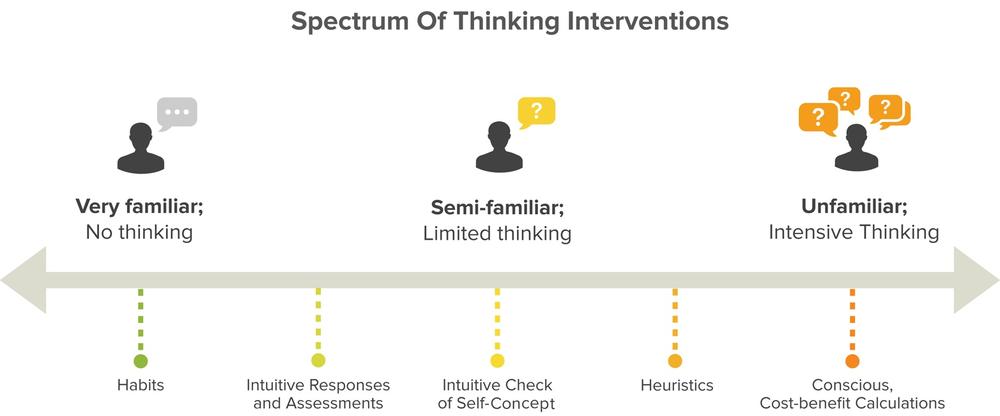

We’ve talked about a range of ways by which the mind decides what to do next—from habits and intuitive responses to heuristics and conscious choices. Table 1-1 lists where each of these decision-making processes often occurs.

Table 1-1. The various tools the mind uses to choose the right action

MECHANISM | WHERE IT’S MOST LIKELY TO BE USED |

|---|---|

Habits | Familiar cues trigger a learned routine |

Other intuitive responses | Familiar and semi-familiar situations, with a reaction based on prior experiences |

Active mindset or self-concept | Ambiguous situations with a few possible interpretations |

Heuristics | Situations where conscious attention is required, but the choice can be implicitly simplified |

Focused, conscious calculation | Unfamiliar situations where a conscious choice is required or very important decisions we direct our attention toward |

As you look down this list, they are ordered in terms of how familiar the situation is in our daily lives, and how much thought is required. That’s not accidental; the mind wants to avoid work, and so it likes to use the process that requires the least thought. Unfamiliar situations (like, for most people, math puzzles) require a lot of conscious thought. Walking to your car doesn’t.

But that’s doesn’t mean that we always use habits in familiar situations, or we only use our conscious minds in unfamiliar ones. Our conscious minds can and do take control of our behavior, and focus very strongly on behaviors that otherwise would be habitual. For example, I can think very carefully about how I sit in front of the computer, to improve my posture; that’s something I normally don’t think about because it’s so familiar. That takes effort, however. Remember that our conscious attention and capacity is sorely limited. We only bring in the big guns (conscious, cost-benefit calculations) when we have a good reason to do so: when something unusual catches our attention, when we really care about the outcome and try to improve our performance, and so on.

You can think about the range of decision-making processes in terms of the default, lowest energy way that our minds would respond, if we didn’t intentionally do something different. Those defaults occur on a spectrum from where very little thinking is required to where intensive thinking is needed (Figure 1-2).

Here are some simple examples, using a person who is thinking about going on a diet and doesn’t have much past experience with diets:

- Eating potato chips out of a bag

Very familiar. Very little thought. Habit.

- Picking out what to get at your favorite buffet bar

Familiar. Little thought. Intuitive response or assessment.

- Signing up for dieting workshops at the office

Semi-familiar. Some thought. Self-concept guides choice.

- Judging whether a cheeseburger will violate your diet’s calorie limit for the day

Unfamiliar. Thought required, but with easy ways to simplify.[35] Heuristic.

- Making a weekly meal plan for the family based on the individual calorie and nutrient counts of hundreds of foods

Unfamiliar. Lots of attention and thought. Conscious, cost-benefit calculations.

As behavior change practitioners, it’s a whole lot easier to help people take actions that are near the potato chip side of the spectrum, rather than the meal plan side. But it’s much harder for people to stop actions on the potato chip side than on the meal plan side. The next two chapters dig deeper into the research to show how you can use the mind’s decision-making process in each case, to help users change their behavior.

That was a lot to take in, I know. Here is a quick snapshot of the most important lessons about how the mind works:

Most of the time, we’re not consciously deciding what to do next.

We often act based on habits. They can be created, but are hard to defeat.

We often make intuitive, immediate decisions based on our past experiences.

When consciously thinking, we often avoid hard work. We “wing it” with rough guesses based on similar, but simpler, problems.

We look to other people, especially peers and experts, for what we should do.

The obvious stuff really matters: making things easy, familiar, rewarding, beautiful, urgent, and feasible.

[9] That’s the “third-person effect” in communications research ([ref43]). See http://www.spring.org.uk/2010/08/persuasion-the-third-person-effect.php for a recent write-up.

[10] There is actually a family of theories, so dual process theories would be more accurate, but cumbersome. Dual process theories give a useful abstraction—a simplified but generally accurate way of thinking about—the vast complexity of our underlying brain processes.

[11] There are great books about dual process theory and the workings of these two parts of our mind. Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011) and Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink (Back Bay Books, 2005) are two excellent places to start; I’ve included a list of resources on how the mind works (including dual process theory) in Appendix B for those who are curious.

[12] For example, biases and heuristics in our decision-making process—the role of these mental slants and shortcuts is discussed further in this chapter.

[13] This particular list of “A” words comes from Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_biases_in_judgment_and_decision_making. Their partial list of biases in judgment and decision making has 166 different mechanisms! Wikipedia obviously isn’t authoritative, but it gives you an idea of the problem. The descriptions, examples, and citations are my own.

[14] Dan Lockton’s Design with Intent Toolkit organizes 101 design patterns for behavior change ([ref119]). In Yes!, Noah Goldstein lists 50 mechanisms for persuasion ([ref83]). The Marketing Science Institute lists 42 mechanisms that marketers use ([ref2]). Eric Fernandez presents 104 in “A Visual Study Guide to Cognitive Biases” (2010). And there are many more.

[15] The boundaries between “habit” and other processes (“intuition,” etc.) are somewhat blurry; but these terms help draw out the differences among types of System 1 responses. See [ref184] for the distinction between habits and other automated System 1 behaviors; see [ref101] for a general discussion of System 1 behaviors.

[16] I’m indebted to Neale Martin for highlighting the situations in which the conscious mind does become active. See his book Habit (2005) for a great summary of the literature on when intuitive and deliberative processes are at play.

[17] This isn’t to say that the rider is equivalent to the left side of the brain and the elephant to the right side. Our deliberative and intuitive thinking isn’t neatly divided in that way. Instead, this is just one of the many examples of how rationalizations occur when our deliberative mind is asked to explain what happens outside of its awareness and control. Many thanks to Sebastian Deterding for catching that unintended (and wrong!) implication of the passsage.

[18] I’m indebted to Sebastian Deterding for helping clarify and hone this section (among many other sections, but this one in particular).

[19] The game is known as the Iowa Gambling Task and has been used in dozens of studies of cognition and emotion.

[20] See [ref12] for a discussion of the four core characteristics of automatic behaviors, such as habits: uncontrollable, unintentional, unaware, and cognitively efficient (doesn’t require cognitive effort).

[21] There’s a nice summary and video here: http://newsinhealth.nih.gov/issue/jan2012/feature1, http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18560_162-57423321/hooked-why-bad-habits-are-hard-to-break/

[22] There’s an active debate in the field about how exactly the notion of a reward affects a person after the habit is formed. See [ref184] for a discussion.

[23] See [ref18] on the difference between “wanting” and “liking.” The difference between wanting and liking is a possible explanation for why certain drugs instill strong craving in addicts although taking them long stopped being pleasurable.

[24] Duhigg’s story also is an example of the complex ethics of behavior change. Hopkins accomplished something immensely beneficial for Americans and American society. He also was wildly successful in selling a commercial product in which demand was partially built on a fabricated “problem” (the fake problem of tooth film, which is harmless, rather than tooth decay, which is not).

[25] This is one form of “motivated cueing,” in which there is a diffuse motivation applied to the context that cues the habit ([ref184]). There is active debate in the field on how, exactly, motivation affects habits that have already formed.

[26] I’m using the term “frames of reference” to encompass the range of processes that show we have multiple potential reactions to the same stimulus, depending on our current context and what is top of mind. Schemas, priming, framing, and self-narratives all affect our choice set and salient associations and thoughts. Each process has distinct characteristics and research literatures. Priming, for example, is usually relevant for short-term changes in behavior, and self-narratives are (more) relevant for longer-term changes in behavior. But the lesson for product designers is the same—our moment-to-moment selves, and thus the actions we decide to take, are subject to cues in our environment.

[27] There is considerable recent debate in psychology over the presence and interpretation of priming effects ([ref22]), centering on another famous study by [ref12] with college students primed to think about ageing before walking down a hallway (those primed to think about ageing walked more slowly). More recent research by [ref53] argues that priming didn’t influence the participants—but rather the expectations and subtle cues from the researchers themselves, who knew what the students had been primed with.

Here, I am not trying to wade into the debate over priming, but rather making the more general point that there are a variety of mechanisms by which our intuitive minds shape our behavior in response to selective activation (and interpretation) of our memories and internal concepts.

[28] In fact, many of the hundreds of biases and heuristics that are discussed in the literature are redundant—special cases of general rules that our mind follows. See [ref161] for one way to organize and make sense of the literature on heuristics.

[30] See Cialdini’s Influence (HarperBusiness, 2001) for an overview of social proof.

[31] [ref33]’s work provides a good practical overview. See [ref34] for a framework to understand various social conformity pressures.

[32] See Roy F. Baumeister and John Tierney’s book Willpower (Penguin Books, 2011) for a good general-public summary of the research into willpower, and Kathleen D. Vohs and Baumeister’s Handbook of Self-Regulation (The Guilford Press, 2011) for the underlying academic research.

[33] In this case, one could argue that limiting the search of movies is an optimal strategy from a global decision making perspective. True, and economists and game theorists subsequently have made that argument. But Simon’s core finding holds—we don’t try to find the optimal solution to problems.

[34] That is, the natural “clustering” of positive and negative perceptions. See [ref101] for a discussion of this clustering. [ref6] also gives some great examples of the importance of good visual design on behavior.

[35] One such commonly used heuristic is the volume of the food—yes, how big it is. Barbara Rolls, head of the Penn State Human Ingestive Behavior Lab, developed a diet that leverages this heuristic to help people lose weight (see [ref154] and http://nutrition.psu.edu/foodlab/barbara-rolls). [ref181] has a humorous, readily accessible (“digestible”?), description of this research.

Get Designing for Behavior Change now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.