Preface

Building a Cleaner, Greener Internet

Goliath and Frank: A Holiday Tale

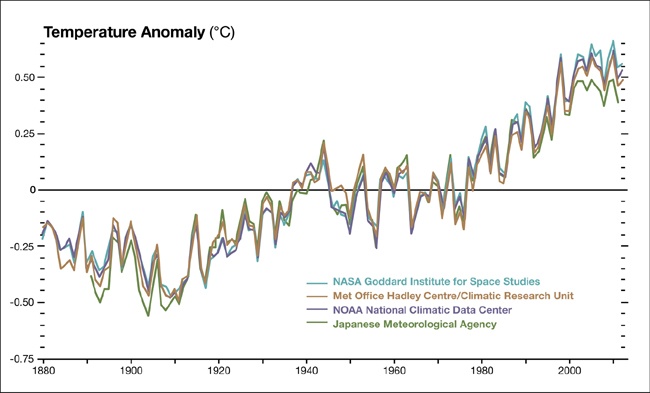

As I write this in upper Michigan during the last days of 2015, the year is poised to take the title of hottest on record,[1] broken from the previous year in 2014. I recently rode my bicycle on snow-free roads, wearing a light jacket just a few miles from what has been named by The Weather Channel as the third snowiest city in the United States.[2]

In fact, many places in the eastern United States reported the warmest Christmas Eve on record, with Fahrenheit temperatures ranging from 20° to 30° higher than average.[3] New York City, Philadelphia, and other eastern seaboard cities reported temperatures in the low to mid-70s. Burlington, Vermont reported its highest December temperature ever at 68°. In total, more than 6,000 temperature records were broken in the United States alone during December 2015.[4]

Shortly thereafter, a single storm systemâaptly named Winter Storm Goliath by The Weather Channel (but called Frank by weather agencies in the United Kingdom and Ireland[5])âencompassed more than half the United States. With it came a string of at least 55 tornadoes over a seven-day period that destroyed numerous homes and killed 20 people,[6] making it the deadliest December for tornadoes in 62 years.[7] Record-breaking blizzards in western Texas and New Mexico brought heavy snowfall and drifting of epic proportions, causing New Mexico to declare a state of emergency. One New Mexico couple was stranded in their car for nearly 20 hours under 12 feet of snow. Texas and New Mexico dairy farmers lost an estimated 30,000 cattle during the storm.[8] Goliath also brought the worst flooding to hit the Mississippi River since the Great Flood of 1993, in some places even surpassing those flood levels.[9] It took well into January for water levels in the mid-South and lower Mississippi valleys to subside. Missouri declared a state of emergency, as well. In addition, Goliath brought snow and hazardous travel conditions throughout the Midwest and Northeast United States, canceling more than 2,800 flights with another 4,800 delayed at airports across the country, leaving hundreds of thousands without power.[10]

Not surprisingly, the storm left a swath of death and destruction in its wake, with at least 52 people killed and an as yet indeterminate amount of damage to property. Although The Weather Channel called it the deadliest storm of 2015,[11] the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) noted that it was just one of ten storms in 2015 that exceeded the $1 billion mark in losses.[12]

The stormâs path then continued into Europe, and its name was changed to Frank as it gained momentum from warmer waters of the Gulf Stream. By the time Frank hit Iceland, it had atmospheric pressure similar to some of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded, putting it into the top five of all Northern Atlantic storms.[13] In Northern England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, high winds, waves, and rain pounded an area already dealing with historic flooding. Over the North Sea, the storm caused an oil barge to break loose and drift out of control in the violent waves, costing one life and forcing BP to evacuate its Valhall oil field.[14]

When Goliath/Frank hit the North Pole, where average December temperatures hover around â15° F to â20° F below zero, the warm air from the Atlantic tropics pushed temperatures as high as 32+° F above zero, a temperature fluctuation of 50+° F higher than normal, something that has been seen only three times since 1948.[15] Let that soak in for a second: the North Pole was above freezing at a time when 100% of its days are bathed in darkness.

Three weeks later, another major storm blanketed the mid-Atlantic and Northeast with up to 42 inches of snow, left 250,000 people without power, closed down New York City and Washington, DC, and left up to 48 people dead.[16] The estimated economic impact of that storm was $850 million.

Think these stories sound like something out of a Hollywood movie like The Day After Tomorrow? Unfortunately, this is not the stuff of fiction. Although some scientists warn of exploiting extreme weather events to promote climate change,[17] the majority agree that as global temperatures rise over time,[18] so does the likelihood of more intense storms, something the world clearly saw with Goliath/Frank.

So what, pray tell, does any of this have to do with becoming a better designer? (That is why you picked up this book, right?)

Connecting the Dots

How do we connect the dots between extreme weather stories and designers building mobile apps? They donât seem related, right? Well, everything we do has some sort of impact. Yes, something as innocuous as designing a web page, buying a coffee, eating dinner, or even breathing produces waste of some sort. Collectively, when applied to the 7.4+ billion people on the planet, that impact really adds up.[19]

One of the many challenges associated with the climate crisis is connecting the dots between extreme weather events like those noted earlier and personal or organizational behavior. When you bone-up on climate science basics and realize the depth of the situation weâre in, it can feel overwhelming and hopeless. One wonders how a single person or small business could possibly have an impact on something as monumental as a melting glacier, rising seas, or years-long drought.

When you compound that with a political and economic climate that can often fuel personal apathy, it is not surprising that many donât feel compelled to act. Here are two examples:

Senator James Inhofe, 2015 chair of the US Senate Committee on Environment and Public Worksâmistaking weather for climate (see the sidebar on page xiii)âthrew a snowball to the sitting Senate President on the Senate floor in an effort to disprove global warming because it was unseasonably cold outside.[20]

An investigation in 2015 unearthed evidence that Exxon (now ExxonMobil) was aware of climate changeâs impact as early as the 1980s but chose to cover it up for more than 40 years.[21]

With stories like these bombarding us every day, it is easy to feel overwhelmed, complacent, and apathetic. Even if you do personally aspire to make a difference, reducing your carbon impact doesnât typically touch the heart in the same way as, say, donating money to cure cancer or volunteering at a homeless shelter might. You have to really like statistics and trust in our collective efforts to make a future difference in order for that to happen. Not everyone is hardwired to think that way.

Fossil fuel companies arenât going to stop selling oil any time soon, but we can make better choices about fuel and transportation that add up. The plummeting price of renewables has already put a noticeable dent in their market share. Companies, universities, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the planet are divesting from fossil fuels, and the tide is shifting.

Plus, individuals do find transformative ways to make a real difference. Climate Ride, a small, virtual nonprofit, is a great example. The organization empowers everyday people to collectively raise millions of dollars and bike tens of thousands of miles to help environmental organizations around the United States. Their multiday hiking and cycling events are transformative experiences for the people who participate, helping Climate Ride build a closely knit community of people banding together to make a difference. Plus, the money raised helps not one or two but more than 150 environmental organizations with key funds that drive change in sustainability, conservation, climate education, and active transportation advocacy efforts.

One Designerâs Impact

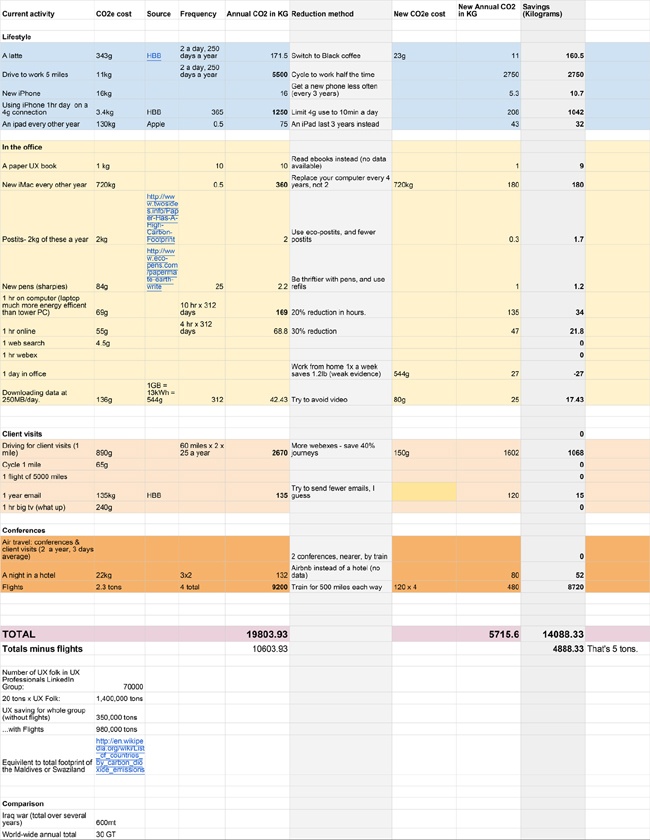

To get a better understanding of an individualâs impact, hereâs an example from someone profiled later in this book. US-based user experience (UX) designer James Christie tracked the annual carbon footprint of common tasks associated with his job in a public spreadsheet: conference travel, client visits, buying a latte, driving to work, Post-it use, book purchases, and even email and webinars attended.[22] Turns out that James produces about 20 tons of CO2e annually just by going to work, as do most Americans (in developing countries, that number is around three tons).

So should James stop going to work? Of course not. Could he explore more environmentally friendly ways to accomplish the same things in his day-to-day work life, such as telecommuting or riding his bike? Absolutely.

Knowing and understanding your individual impact is a great first step toward making changes that collectively add up. James also included a reduction column in his spreadsheet so that he can compare current behaviors with potentially more sustainable alternatives.

This also doesnât mean you should live in a yurt without power either. Your lifestyle choices are just that: choices that you should personally feel comfortable with. This book doesnât intend to shame you out of sharing cat videos; rather, itâs meant to help you make more educated decisions about online conduct. It is through our collective actions that we can make a difference. Or not. Itâs up to us.

Click Clean

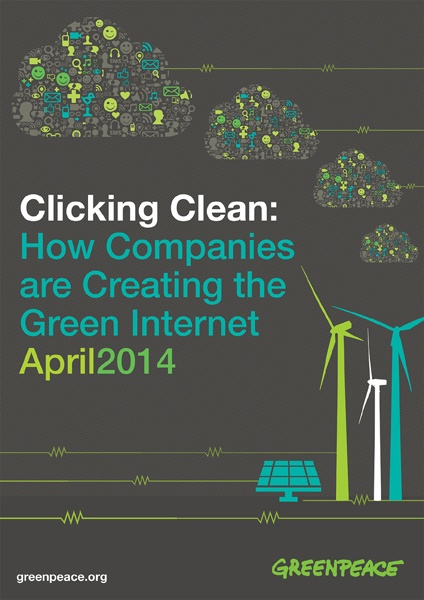

Greenpeace USA produces an annual report called Clicking Cleanâfocused squarely on the Internet and information and communications technologies (ICT)âthat details examples of the impact our personal choices have on the environment and world energy consumption.

One of the stats in the 2014 report noted:

If the Internet were a country, it would be 6th largest user of electricity behind China, the US, Japan, India, and Russia.

Thatâs a lot of electricity. And the data is from 2011. Think about how much the Internet has grown since then. When we consider this, one can see that our tweets, Facebook updates, blog posts, websites, and so on, are pumping large amounts of CO2e into the atmosphere.

Then thereâs Tweetfarts. Based on their research, a single tweetâabout 200 bytes worth of dataâgenerates about as much CO2e as a human fart. As of this writing, Twitter uses only 10% renewable energy to power its servers, according to Greenpeaceâs Click Clean Scorecard app. With 500 million daily tweets in 2012, Twitter alone generated 10 metric tons of CO2e every day. Tweetfarts uses humor to put this impact into perspective. If you look at the Internet at large, including video, voice, and other cloud-based services, that number jumps to 830 millions tons of CO2e annually.[24]

Although the majority of emissions come from data centers, a portion of the CO2e released by the Internet happens on the frontend, too. A Harvard study estimated that content-heavy news sites can release more greenhouse gases than their printed counterparts if their pages are left open for extended periods of time.[25] And who hasnât left their browser tabs open in the background while they work?

Streaming video services like Netflix or Hulu play a big role, too. Imagine how many people stream the new season of House of Cards or Orange Is the New Black when they come out. In the first quarter of 2015 alone, Netflix users watched a collective 10 billion hours of streaming media.[26] Netflix and YouTube accounted for over half of peak Internet traffic in North America as of 2013.[27]

Given how quickly the Internet is growing, weâre looking at a billion tons of annual CO2e emissions in the very near future.

But Isnât Virtualization a Good Thing?

For many, the most promising answers to solving the climate crisis lie in technology, be that clean tech or through the process of converting resource-intensive physical products to more lightweight online services. American entrepreneur, investor, and software engineer Marc Andreessen famously said in a 2011 Wall Street Journal article that âsoftware is eating the worldâ and noted that âwe are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.â[28]

The ability to deliver software on a global scale has led to a digital/information economy that the United Nations estimates is in excess of $15 trillion for business-to-business (B2B) and another $1.2 trillion for business-to-consumer (B2C) with both expanding rapidly (the latter faster than the former). And that is just ecommerce. The UNâs 2015 Information Economy Report doesnât take into account the amount of money saved by companies as they convert resource-heavy physical products to online services through the process of transmaterialization (a term weâll cover in Chapter 5).[29]

In the Q4 2015 edition of Digitalist magazine, authors Kai Goerlich, Michael Goldberg, and Will Ritzrau researched six industriesâutilities, transportation and logistics, manufacturing, retail and consumer products, agriculture and food production, and construction.[30] Based on a study by the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) and Accenture, the authors estimated that these six industries could collectively cut 7.6 gigatons of emissions by using technology to digitize business processes and data to drive decisions about resource use.[31] Thatâs a huge reduction! But it doesnât necessarily solve the problem. All those digitized business processes require hosting in data centers. They all are accessed by users with tablets, laptops, and smartphones. All these things run on electricity.

Meanwhile, as politicians grapple with posturing and horse trading over who is responsible for what when it comes to climate change, companies large and small are working on a wide range of options like carbon capture, biofuels, power storage, hydrogen fuel cells, cheaper renewables, and so on. At the same time, scientists focus on more speculative technologies, like cold fusion, all in the name of maintaining steady economic growth while also cutting carbon emissions. As journalist Eduardo Porter notes in The New York Times, âWe might be able to pull it off. But it will take an overhaul of the way we use energy, and a huge investment in the development and deployment of new energy technologies.â[32]

It is inspiring when large tech companies such as Google and Facebook choose to power their data centers by renewables, but what about the rest of us? Tech companies have taken the lead on this front, but they are not the only ones responsible for the Internetâs impact on energy. For example, according to research by online marketing platform Agency Spotter, there are about 560,000 agencies worldwide, 120,000 of which are in the United States.[33] This includes design firms, advertising companies, marketing and PR agencies, software developers, and so on. People at these agencies make decisions every day about how to design, build, and host hundreds of millions of web pages. In conducting interviews for this book, I found that very few of the agencies or freelancers I spoke to consider sustainability or renewable energy when making decisions about their work.

Often, instead of focusing on efficiency and clean power, agencies create slow, unreliable digital products and choose cheap hosts like GoDaddy (13 million customers) or HostGator (9 million customers) to house their pages. Similar to other industries, like fast food or fast fashion, buying products and services from these providers is an unhealthy decision that supports a broken system. The lack of transparency in the web hostingâonly industry also makes it very easy to greenwash. If all these agencies had easy, affordable access to reliable green hosting services, there is an opportunity to mitigate far more emissions than the 7.6 gigatons mentioned earlier.

Every single one of these technology-based solutionsâwhether business facing or consumer facing, whether created by agencies, startups, or scientistsâwill have users who need to access information quickly and efficiently. They will run on servers that require redundancy of data and electricity 24/7/365. These tools should be built with the same attention to our planetâs future as the solutions they intend to provide. Pixels require electricity. Thankfully, we have seen unprecedented adoption of renewables by tech companies, but we still have a very long way to go. Creating a more sustainable future for the digital economy is the problem this book addresses.

Renewables versus efficiency

President Obamaâs Climate Action Plan is well known for its ambitious endeavors to avoid six billion metric tons of carbon through the year 2030, the most high-profile action of which is to enforce emissions caps on power plants, which, if all goes according to plan, will cut power-sector emissions by 32%.[35]

A far lesser-known but arguably more ambitious component of the Presidentâs plan is an energy efficiency effort known as âappliance and equipment standards.â It is on track to slash three billion tons of emissions by 2030 through new standards in energy efficiency for American products. Shortly after being sworn into office, the president spoke of a ârevolution in energy efficiencyâ and even went so far as to declare energy efficiency âsexy.â Since then, as many as 39 new standards were set by the Department of Energy (DOE) for everything from refrigerators and clothes dryers to pool heaters, air conditioners, and lightbulbsâbut no digital products or services.

With efficiency being a key component of the Climate Action Plan and the DOE upping the pace of creating new standards, US power demand has flattened out after decades of growth, âaverting the need for new plants while saving consumers billions of dollars,â according to a Politico piece by Michael Grunwald.[36] These new standards are part of a larger set of efficiency initiatives that extend to fuel efficiency for heavy trucks and automobiles, and extensive efforts to green the government, including the Pentagon, resulting in the lowest federal energy use in 40 years.

Efficiency and usability should sit alongside renewables as key strategies when building more sustainable digital products and services. Sure, at a time when many websites are the digital equivalent of Humvees, itâs a high aspiration, but the stakes are pretty high too.

Consider this: on July 8, 2015, technical difficulties grounded all mainland United Airlines flights, took down the New York Stock Exchange for a day, forced China to suspend trading for 45% of its stock market, and The Wall Street Journal went offline, as well. Although some folks told us not to panic,[37] others very clearly stated that we should worry and that the reason we should worry was simple: software sucks.[38]

âItâs hard to explain to regular people how much technology barely works, how much the infrastructure of our lives is held together by the IT equivalent of baling wire,â says Quinn Norton in a Medium post titled âEverything Is Broken.â[39] To create a more sustainable Internet, we also need to build more forward-thinking and efficient solutions. The sections of this book on UX, content strategy, and performance optimization are driven by efficiency.

Taking all this into consideration, when it comes to our own actions and creating more sustainable digital products and services, we need to ask two important questions:

How can we power our work with renewable energy?

How can we make our products and servicesâand the user experiences they offerâas efficient as possible?

As we shall see in this bookâs pages, those two questions can quickly become complicated. But they also offer tremendous opportunity.

Awareness and the consumer problem

If they consider it at all (and most donât), many people think the Internet is a green medium: after all, it replaces paper, why wouldnât it be green? However, although saving paper makes environmental sense, it might surprise many that sending an email, running a Google search, or tweeting are all actions that have an environmental impact. Plus, there is misinformation everywhere: âDiscussion boards like Quora are full of âexpertsâ laughing at the impact of the Web on sustainability,â says author and professor Pete Markiewicz. âConsumers get false information on the topic by techno-utopians.â

Although the impact of a single tweet is small, when you multiply it by the number of people on this planet who send, search, and post each dayâover half the worldâs population, by some calculations with a total of 7.6 billion expected by 2020âthat impact becomes much, much larger.[40] Unfortunately, many people havenât considered the negative effect the energy used to power the Internet has on our planet.

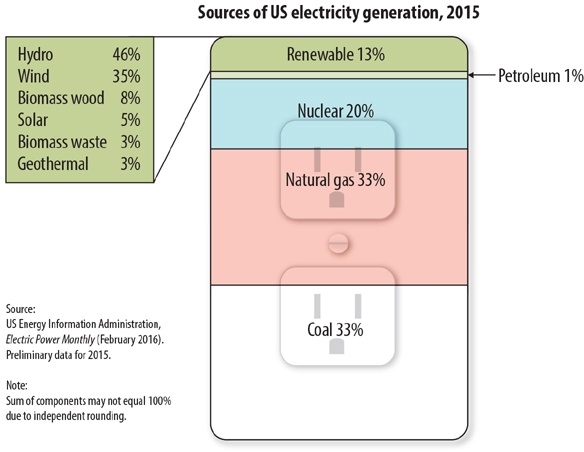

Every photo you share, every page you browse, every movie you stream on Netflix, essentially everything you do on a computer, mobile phone, smart TV, or other device connected to the Internet requires electricity to host, serve, stream, display, and interact with. And though things are improving, the majority of that electricity still comes from nonrenewable resources like coal or natural gas. In fact, in the United States alone, only 13% of our power comes from renewable resources, according to the US Energy Information Administration.[41]

Raising awareness is also another important component of moving toward a more sustainable Internet. People need to know this is a thing.

B the Change: Why I Wrote This Book

Many of the companies featured in this book are certified B Corps. These companies, which number in the thousands, are part of a global movement to redefine success in business, using the power of business to solve social and environmental problems. They range from consumer product brands such as Patagonia, Fetzer Wines, New Belgium Brewing, Ben & Jerryâs, and Method cleaning products to B2B companies like Rubicon Global, Arabella Advisors, Community Wealth Partners, and Cascade Engineering. Data-heavy digital companies like Etsy, Hootsuite, and Kickstarter are part of this community, as well.

In my experience, B Corps, specifically the segment of the B Corp community that focuses on digital products and servicesâmarketing firms, web agencies, and software companiesâare blazing the trail toward a more sustainable Internet. Companies like DOJO4, Open Concept Consulting, Etsy, Manoverboard, Canvas Host, Green House Data, Exygy, and others have implemented practices within their companies or otherwise pushed the idea of more sustainable digital products and services forward. Some have partnered with nonprofits like Green America or Greenpeace to promote clean cloud advocacy campaigns. DOJO4, for instance, has worked with Greenpeace to enhance its Click Clean Scorecard Chrome extension (http://www.clickclean.org)âwhich helps users better understand which of their favorite websites are powered by renewable energy.

Each B Corp solves social and environmental problems in their own unique way. Certified B Corps undergo a rigorous assessment process that helps them gauge performance around accountability, transparency, social mission, and environmental impact. B Corps make profit, but they align that profit with purpose to serve all stakeholders, not just shareholders. This rigorous assessmentâknown as the B Impact Assessment (http://www.bimpactassessment.net)âhelps a company look carefully at each component of its business and ascertain whether all stakeholder needs are being met, such as the following:

Are employees paid a living wage?

Does the company recycle?

Is profit-sharing offered?

Does the company employ a significant percentage of minorities or people from communities with less opportunity for personal advancement?

Is there gender equity in the company?

Are community volunteer programs available?

How much does the company give to charity?

Does the company measure its energy use?

Does the company invest in renewables?

Does the company have a board of directors or advisory committee to help guide it through difficult business decisions?

There are hundreds of questions like the preceding ones in this assessment. Broken down into five categoriesâEnvironment, Workers, Customers, Community, and Governanceâthese questions guide companies down a path to building a better business that does well while also doing good.

Many questions in the Environment category focus on a companyâs supply chain:

Where does the company get its supplies?

Can waste be removed from the process of procuring, using, and disposing of supplies?

Do vendors also make appropriate social or environmentally responsible decisions?

It was in working through the answers to many of these questions that my own thinking around how we can build a more sustainable Internet evolved.

B Mighty

My company, Mightybytes, a digital agency started in 1998 and located in Chicago, has been a certified B Corp since 2011. Becoming a B Corp is one of the best business decisions Iâve made and has provided our team with a clear roadmap for building a better, more conscientious company. Because many of the questions in the B Impact Assessment are related to supply chainâsomething I knew very little about in 2011âtaking it got me thinking about what sort of environmental impact a primarily all-digital company that designs websites and creates software solutions might have. Weâre not manufacturing physical products. We donât source materials like fabric or plastics from offshore suppliers. At best, outside of our core employee team, the rare office supplies purchase, and occasional freelancers, we donât have a lot of suppliers. So our supply chain, I thought: green.

Except that everything we build requires electricity to run.

When the power goes out, what we build disappears. The servers that host the products and services we create require electricity 24/7/365. Some of these sites get a lot of traffic, which leads to electricity use in data transmission and on the frontend user side, as well. Suddenly, we realized that our little company was a bigger part of the problem than we originally thought. So, as we completed the B Impact Assessment for the first time in 2011, I began thinking about ways in which we could minimize the impact of the digital products and services we build. How could we make websites, apps, and digital marketing campaigns more energy-efficient and user-friendly?

As business, and the virtualization of business processes, is a primary force driving Internet growth, it is important for a book covering this topic to feature companies that will invest in a more sustainable future while exploring the value digital products and services can bring to their organizations. I have found B Corps to be these companies. Many of the ideas and concepts within this book were either tested on or run by fellow members of the B Corp community before implementing them as practices within our own company. They have provided valuable support and wise insights throughout the life cycle of this book.

B Corps, of course, are not the only game in town. Conscious companies and sustainable brands that pay attention to the triple bottom lineâpeople, planet, prosperityâare cropping up all over the world to redefine success in business. There are also many nonprofits working toward more sustainable technology solutions. BSRâs Center for Technology and Sustainability, The Green Grid, and specific campaigns within organizations like Greenpeace or Green America are good examples. Most of these efforts, however, focus specifically on data centers and pay little to no attention to design or frontend use.

The rigorous assessment used by B Corps provides, in my opinion, the clearest measurable roadmap for building and growing a socially and environmentally conscious business, which is directly related to the mission of this book. The data tells the story. Plus, when it comes to focusing on issues of sustainable design and UX, I have found that these companies are far ahead of comparable businesses that pay attention only to profit. That is why I have included so many of them in this book.

Who Should Read This Book

This book is primarily written for those who design, build, and manage digital products and services. Whether you are a product manager, a site owner, a UX designer, a frontend developer, a content strategist, or a unicorn who does all the above, you will hopefully find something useful within these pages.

As it covers an area often neglected in sustainability assessments, sustainability or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) professionals should find some useful ideas within these pages, as well. Several pros have offered their expertise throughout each chapter on topics not typically covered in standard sustainability assessments.

Here are some willful intentions for this book:

Inspire readers to think about and be more aware of web sustainability alongside bigger sustainability issues.

Encourage web design and development teams to connect efficiency, reliability, usability, and sustainability so that they can make better choices in their work.

Help sustainability and CSR professionals better understand Internet sustainability so that it can be folded into their existing work.

Provide readers with the knowledge necessary not only to be inspiring design leaders but also environmental advocates, as well.

Finally, to inspire people who create and build the Internet to power it with renewable energy.

How This Book Is Organized

Book chapters begin and end with learning objectives. At the beginning of each chapter, expectations are set for what you will learn in that chapter. At the end, next step tasks are offered to translate concept into action.

Chapter 1 defines sustainability and frames the conversation with statistics and research on the overall environmental impact of the Internet.

Chapter 2 outlines a framework for designing more sustainable digital products and services.

Chapter 3 through Chapter 6 dive deeper into each category of the aforementioned framework: design and UX, content, performance optimization, and green ingredients, including green hosting.

Chapter 7 includes research on devising meaningful ways to measure the environmental impact of digital work.

Chapter 8 posits what a more sustainable future Internet might be.

Sidebars, interviews, and callouts throughout each chapter highlight specific topics, definitions, or complementary content.

Letâs Go!

Thank you for choosing this book. It has been a labor of love several years in the making. Now that I have told the backstory and set the stage, I hope you enjoy what follows.

[1] Jonah Bromwich, âA Fitting End for the Hottest Year on Recordâ, New York Times, December 23, 2015. (http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/24/science/climate-change-record-warm-year.html?_r=1)

[2] Michael H. Babcock, âHancock Named â3rd Snowiest Cityââ, The Daily Mining Gazette, December 20, 2010. (http://www.mininggazette.com/page/content.detail/id/518181/Hancock-named--3rd-snowiest-city-.html?nav=5006)

[3] Brett Rathbun, âWarm Christmas Eve Shatters Records Across Eastern USâ, AccuWeather.com, December 26, 2015. (http://www.accuweather.com/en/weather-news/warmth-record-high-temperatures-northeast-southeast-christmas-2015/54388777)

[4] Chris Dolce, â6 Incredible Facts About Decemberâs Warmthâ, The Weather Channel, December 22, 2015. (http://www.weather.com/news/weather/news/weird-facts-december-2015-warmth)

[5] Wikipedia, â2015â16 UK and Ireland Windstorm Seasonâ. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015%E2%80%9316_UK_and_Ireland_windstorm_season)

[6] The Weather Channel, âTornadoes and Flooding Rain Hit the South, Midwest Christmas Week 2015â, December 28, 2015. (http://www.weather.com/storms/tornado/news/storms-tornadoes-christmas-week-december-21-28-2015)

[7] The Weather Channel, âTornadoes: Deadliest December in 62 Yearsâ, December 28, 2015. (http://www.weather.com/news/weather/video/tornadoesdeadliest-december-in-62-years)

[8] Ada Carr, âDairy Cow Death Toll to Surpass 30,000 in Texas, New Mexico Due to Winter Storm Goliathâ, The Weather Channel, January 1, 2016. (http://www.weather.com/news/news/dairy-cows-winter-storm-goliath-texas-new-mexico)

[9] Jon Erdman, âHistoric Winter Flood Along Mississippi River Sets Record in Cape Girardeauâ, The Weather Channel, January 6, 2016. (http://www.weather.com/news/news/mississippi-river-flooding-december-2015)

[10] The Associated Press, âLatest: More Than 2,800 Flights Canceled Amid Winter Stormâ, December 29, 2015. (http://bigstory.ap.org/article/19191dfd426042d5979cafa87e188a40/latest-weather-forces-i-40-closure-new-mexico-texas)

[11] Andrew MacFarlane, âGoliath: The Deadliest U.S. Storm System of 2015â, The Weather Channel, December 31, 2015. (http://www.weather.com/news/news/goliath-deadliest-storm-of-2015)

[12] National Centers for Environmental Information, âBillion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Table of Eventsâ. (http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events)

[13] Andrew Freedman, âHistoric Storm Set to Slam Iceland, Northern UK with Hurricane-Force Windsâ, Mashable, December 28, 2015. (http://mashable.com/2015/12/28/freak-atlantic-storm-uk-frank/#4CbtAB7_haqJ)

[14] Don Melvin, âOne Killed, Oil Rigs Evacuated, Barge Drifts Loose in Violent North Seaâ, CNN, December 31, 2015. (http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/31/europe/bp-evacuation-north-sea-oil-field)

[15] See meteorologist Bob Hensonâs December 28, 2015 tweet. (https://twitter.com/bhensonweather/status/681685436264132608)

[16] Sean Breslin, âWinter Storm Jonas: At Least 48 Dead; Roof Collapses Reported; D.C. Remains Shut Downâ, The Weather Channel, January 26, 2016. (https://weather.com/storms/winter/news/winter-storm-jonas-impacts-news)

[17] John Michael Wallace, âConfronting the Exploitation of Extreme Weather Events in Global Warming Reportingâ, The Washington Post, February 28, 2014. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2014/02/28/confronting-the-exploitation-of-extreme-weather-events-in-global-warming-reporting)

[18] Union of Concerned Scientists, âIs Global Warming Linked to Severe Weather?â. (http://www.ucsusa.org/global_warming/science_and_impacts/impacts/global-warming-rain-snow-tornadoes.html#.VogKaxqAOko)

[19] Worldometers, âCurrent World Populationâ. (http://www.worldometers.info/world-population)

[20] Wikipedia, âJim Inhofeâ. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Inhofe)

[21] Suzanne Goldenberg, âExxon Knew of Climate Change in 1981, Email Says â But It Funded Deniers for 27 More Yearsâ, The Guardian, July 8, 2015. (http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jul/08/exxon-climate-change-1981-climate-denier-funding)

[22] See âWork and UX Activities Measured in CO2eâ. (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0ApAANR80NbMVdEMxOXNiS1dDZkNjemlmOGdRMVg5VVE&usp=sharing)

[23] Emma Foehringer Merchant, âThe Porter Ranch Methane Leak Was the Worst in US Historyâ, Wired, February 25, 2016. (Source: http://www.wired.com/2016/02/porter-ranch-methane-leak-worst-us-history)

[24] American Chemical Society, âToward Reducing the Greenhouse Gas Emissions of the Internet and Telecommunicationsâ, ScienceDaily, January 2, 2013. (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/01/130102140452.htm)

[25] Pete Markiewicz, âSave the Planet Through Sustainable Web Designâ, Creative Bloq, August 17, 2012. (http://www.creativebloq.com/inspiration/save-planet-through-sustainable-web-design-8126147)

[26] Julia Greenberg, âNetflix Says Streaming Is Greener Than Reading (or Breathing)â, Wired, May 28, 2015. (http://www.wired.com/2015/05/netflix-says-streaming-greener-reading-breathing)

[27] Joan E. Solsman, âNetflix, YouTube Gobble Up Half of Internet Trafficâ, CNET, November 11, 2013. (http://www.cnet.com/news/netflix-youtube-gobble-up-half-of-internet-traffic)

[28] Marc Andreessen, âWhy Software Is Eating the Worldâ, Wall Street Journal, August 20, 2011. (http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111903480904576512250915629460)

[29] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, âInformation Economy Report 2015â. (http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ier2015overview_en.pdf)

[30] Kai Goerlich, Michael Goldberg, and Will Ritzrau, âIs Digital Business the Answer to the Climate Crisis?â, Digitalist, November 18, 2015. (http://www.digitalistmag.com/resource-optimization/2015/11/18/is-digital-business-the-answer-to-the-climate-crisis-2-03765081)

[31] Global e-Sustainability Initiative, âGeSI SMARTer2030â. (http://smarter2030.gesi.org)

[32] Eduardo Porter, âBlueprints for Taming the Climate Crisisâ, New York Times, July 8, 2014. (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/09/business/blueprints-for-taming-the-climate-crisis.html)

[33] Quora, âHow Many Web Agencies Are There in the World in 2014?â. (https://www.quora.com/How-many-web-agencies-are-there-in-the-world-in-2014)

[34] Greenwashing Index, âAbout Greenwashingâ. (http://greenwashingindex.com/about-greenwashing)

[35] WhiteHouse.gov, âPresident Obamaâs Climate Action Planâ, June 2015. (https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cap_progress_report_final_w_cover.pdf)

[36] Michael Grunwald, âThe Nation He Builtâ, Politico, January/February 2016. (http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/01/obama-biggest-achievements-213487?o=3)

[37] Felix Salmon, âYou Donât Need to Panic About the New York Stock Exchange, or Anything Elseâ, Fusion, July 8, 2015. (http://fusion.net/story/163160/you-dont-need-to-panic-about-the-new-york-stock-exchange-or-anything-else)

[38] Zeynep Tufekci, âWhy the Great Glitch of July 8th Should Scare Youâ, The Medium, July 8, 2015. (https://medium.com/message/why-the-great-glitch-of-july-8th-should-scare-you-b791002fff03#.dslmkmns2)

[39] Quinn Norton, âEverything Is Brokenâ, The Medium, May 20, 2014. (https://medium.com/message/everything-is-broken-81e5f33a24e1#.2362w8uqo)

[40] Broadband Commission for Digital Development, âThe State of Broadband 2014: Broadband for Allâ, September 2014. (http://www.broadbandcommission.org/Documents/reports/bb-annualreport2014.pdf)

[41] US Energy Information Administration, âHow Much US Electricity Is Generated from Renewable Energy?â. (http://www.eia.gov/energy_in_brief/article/renewable_electricity.cfm)

Get Designing for Sustainability now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.