Chapter 4. The Glass Experiment

A Truly Wearable Computer

Google Glass, and what happened with Google Glass, has to be one of the most interesting stories in the history of wearable devices. The device came from a surprisingly long history in terms of functionality. It became a major cultural touchpoint and ultimately taught us a lot about where we are in terms of public acceptance of certain technologies. This entire book is about wearable computers, which are basically any devices strapped to your body that perform computation, but Glass belongs to a group of wearables that are truly wearable computers, a general-purpose computational platform that is designed to be worn on the body.

Glass is particularly interesting when you think about its relationship to computers as a whole. As I mentioned in the beginning of the book, we’re approaching the point at which technologies are small and powerful enough to no longer be restricted to what we now consider their traditional forms. Without significant constraints in terms of the size of the technology, we’re free to create computers that are designed from the ground up with our bodies in mind, and a truly wearable computer might make the most sense as the ideal form factor of computers as a whole.

Early Wearable Computers

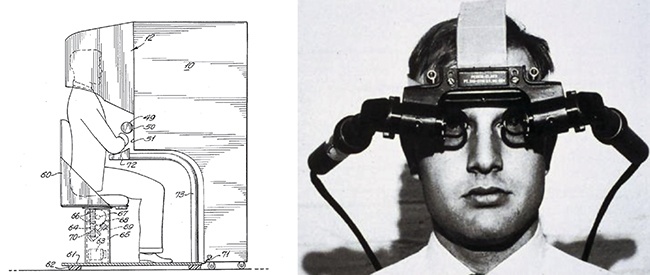

Before computers had an established form factor of terminals with typewriter-style keyboards and big flat monitors, there were a handful of people who built devices that we wouldn’t recognize as computers today. The first of which is Morton Heilig’s Sensorama Simulator (Figure 4-1), which he patented in 1962 and was sort of an early virtual reality system designed for immersive learning.[11] The Sensorama Simulator was one of the first devices specifically designed around our bodies and our senses, including sight, hearing, touch, and even smell. A couple of years later, Ivan Sutherland created an early head-mounted, three-dimensional display nicknamed The Sword of Damocles,[12] which was specifically designed to take advantage of head movement relative to displayed information on the display, creating the illusion of dimensionality of a virtual object.

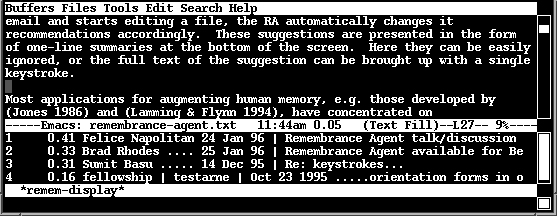

The next big push in the direction of a fully wearable computer came from the MIT Wearable Computing Project in the mid-1990s. The group, colloquially known as The Borgs, focused on developing wearable computers that were meant to be worn constantly.[13] It was here that Thad Starner, who would later become the technical lead for Google Glass, developed the earliest truly wearable computers. In 1993, Starner and fellow Borg Brad Rhodes coded the Remembrance Agent (Figure 4-2), which was a note taking and retrieval program that pulled information from a database of notes from previous conversations.[14] The first reliable wearable computer that Starner built was Lizzy 1, which was a backpack-based system with a Twiddler one-handed keyboard (see Chapter 1) and an early head-mounted display where Remembrance Agent queries would be displayed. Beginning with the Lizzy 1, Starner wore his computers at all times for roughly 20 years, only taking them off to sleep, shower, and when he married (Figure 4-3 shows the Lizzy 2).[15]

The Development of Google Glass

The Google Glass project began in 2010, and according to Google’s chief evangelist, Gopi Kallayil, the first Google Glass prototype took about 90 minutes to construct. He described the process at the Dreamforce conference in 2013 (see also Figure 4-4):[16]

So, it looked like this: a regular laptop computer, like the one you’d carry in your hands, put in a Google backpack that you can buy from the Google store, with wires protruding out of it, mounted on ski goggles, then you can buy off-the-shelf components like still cameras, video cameras, and sticky tape that you get from the supplies cabinet.

After the initial proof of concept, they swapped out the laptop for an Android phone that they taped to the side of a pair of safety glasses. This was the Pack prototype, and it was completed in December 2010 and weighed 3,330 grams.

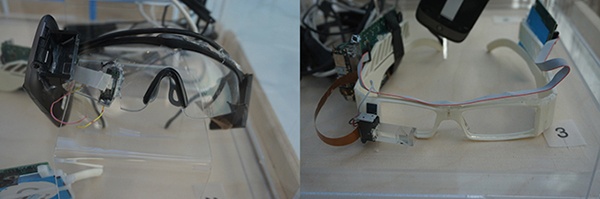

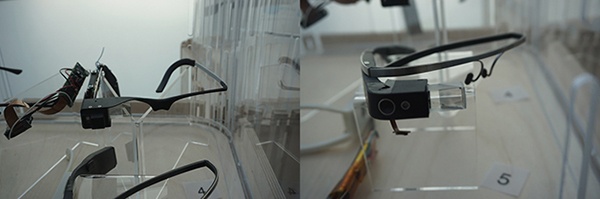

After the Pack prototype, the group focused on making the prototypes lighter and more compact so that they could be worn completely on the head. The first prototype that didn’t require a backpack was the Ant prototype in March of 2011 (Figure 4-5), which weighed 167 grams.[17] Next was the Bat prototype (not pictured), which got rid of the phone case and weighed 115 grams. The Cat prototype, built in May 2011, is the first prototype to use the optics design that would later be in the production version of the Glass. This version weighed 153 grams. The Ant, Bat, and Cat prototypes all were built by repurposing Nexus One phones.[18]

The Lennon prototype (Figure 4-6), completed in April 2011, was a minimalist version of the Glass and was built in parallel with the Ant, Cat, and Dog prototypes. Lennon was built to determine how light the device could be and still be useful. Two Dog prototypes, Dog Metal and Dog Plastic, were built in June 2011 and were the first prototypes in the animal series of prototypes that used higher-end computer boards instead of repurposed phones.

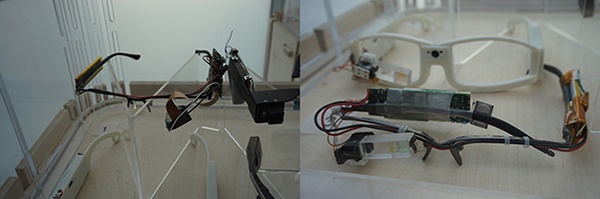

The Emu prototype (Figure 4-7), weighing in at 68 grams, was built in September 2011 and was the first prototype that featured an enclosure. It also was the first prototype that used bone conduction for audio. The Fly prototype was built in October of 2011, less than 11 months after the project began. It was the first fully functional prototype that resembled the more rounded final design.

With the Gnu (December 2011), Hog (February 2012), Ibex (May 2012), and Koala (October 2012) prototypes, the group refined the designs and began user testing. The Hog was the first prototype that was able to be worn publicly, since the project was announced in April.

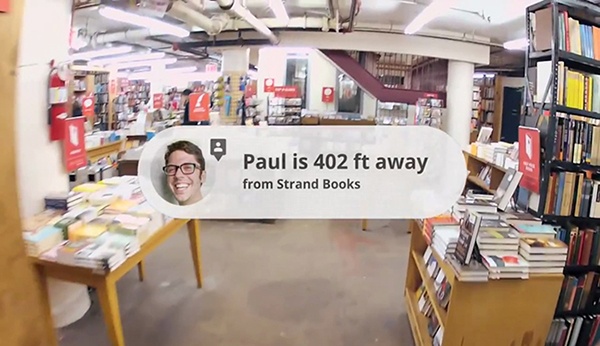

One Day

On April 4, 2012, Google uploaded a video to YouTube called “Project Glass: One Day...”[19] The video didn’t show what the device looked like; rather, it was a concept video that showed what a day might be like with augmented reality (see Figure 4-9). Some of the use cases that were demonstrated were text messaging via voice with the protagonist keeping both hands on his sandwich, a geolocated notification that there was a train delay, and a prompt to take a different route (with turn-by-turn directions). The man even goes into a book store and asks Glass where the music section is located, and it shows him! The end of the video shows the protagonist serenading a young woman with a ukulele via video chat while he shows her his view of a sunset.

The video is accompanied by a post by the “Project Glass” account on Google+ stating, “We think technology should work for you—to be there when you need it and get out of your way when you don’t. A group of us from Google[x] started Project Glass to build this kind of technology, one that helps you explore and share your world, putting you back in the moment.”[20] This is when the internet pretty much exploded. It was all over every blog and news site; it was all anyone talked about.

At the 2012 Google I/O conference, Google cofounder Sergey Brin demonstrated Glass for the first time by having a team of skydivers jump out of a plane above the venue wearing Glass and broadcasting the video feeds live (Figure 4-10). He then announced the first sale of the devices: the US-based developers who were present at the conference could preorder the device for $1,500, and they’d get the devices early 2013. For the rest of 2012, Glass was front and center in the tech news cycle. It was named by Time Magazine as one of the best inventions of the year and even popped up on the runway during New York Fashion Week. Glass was everywhere.

The first Glass Explorer editions shipped in April 2013, almost exactly a year after the initial announcement, and were finally out in the world. They didn’t have a great deal of functionality yet, but they could do certain things like record video, take pictures, get notifications, and display turn-by-turn directions. People were using Glass in new and interesting ways: surgeons were using it to record and broadcast surgeries; citizen journalists livestreamed protests in Istanbul; and athletes trained with them. Even though the devices were interesting and potentially useful, they were largely overshadowed by public criticism around privacy concerns and tech elitism.

Public Backlash

The public backlash against Glass began before the devices were even in the public’s hands. In March, 2013, a month before the product was released, West Virginia signed a bill to ban them while driving,[21] and the first public place to ban their use, the 5 Point Cafe in Seattle, put up signs warning people not to wear the device.[22] This was followed by many other establishments. March 2013 is also when the group Stop The Cyborgs formed to combat Glass and other technologies, distributing signs and stickers stating, “Google Glass is banned on these premises” (Figure 4-11). Most of the concerns were, of course, around privacy—people don’t want to be filmed by other people in public. Another early point of concern was the potential use of facial recognition applications. This eventually prompted Google to publish an update saying that no facial recognition applications would be approved without having strong privacy protections.[23]

The backlash against Glass came to a head in February, 2014 at Molitov’s, a dive bar in San Francisco’s Haight-Asbury District. Tech writer Sarah Slocum was wearing her Glass like normal. When she first arrived at the bar, people were asking her about it and everything seemed fine; just normal people being curious. A few minutes later, though, things began to become more hostile. First, it was a woman turning to her, flipping her off, and yelling “F Google,” this was followed shortly afterward by that same woman yelling, “Get out of here, b!@ch.” That’s when things turned violent. People started trying to rip the glasses off Slocum’s face and throwing bar rags at her. One woman told her, “You’re killing the city,” and finally pulled the device off her face. Slocum eventually got it back, but when she chased the person out of the bar, someone else stole her purse and her cell phone.[24] Over the next few months, there was an attack in the Mission District in San Francisco which involved a woman with a mohawk running up to a writer wearing the device, screaming “Glass,” and ripping them off the man’s face before smashing them on the ground.[25] One other report describes someone in LA’s Venice Beach being robbed of his Glass by someone using a taser.[26]

So how did Glass become such a hated device? You can certainly put some of the blame on privacy concerns; that definitely had a lot to do with it. There’s also “The Walkman Effect,” a concept inspired by the Sony Walkman in the 1980s, by which people can be isolated in public spaces by technology. German psychologist Rainer Schönhammer observed:[27]

This seems to interrupt a form of contact between “normal” people in a shared situation, even if there is no explicit communication at all. People with earphones seem to violate an unwritten law of interpersonal reciprocity: the certainty of common sensual presence in shared situations.

Though social isolation has been a negative talking point since newspapers were invented, Glass was a lot more high profile than most devices and had a lot of social hurdles to get over.

Glassholes

Aside from privacy concerns and the groups that freak out every time something new happens, the third part of the controversy are the A holes that bought the device, or, as they became known, the Glassholes. The overt hatred of Glass users was caused by a perfect storm of technology hype, exclusivity, and income inequality. Google decided to roll out the Explorer program very slowly, initially to a small group at the I/O conference, and then through a contest, personal invites from the original explorers, and eventually to the general public. But even then, you had to have an extra $1,500 lying around to get one. The problem was that Glass was all over the news as a crazy new technology, everyone wanted to try it, but very few people could.

Unfortunately, most of the people who did have the credentials and means to get their hands on it were young, wealthy, white male tech workers in San Francisco and New York, a demographic that is not particularly known for their social skills or tact. Early Glass explorers caused a lot of problems by refusing to take off the device when asked, inappropriately filming people, and being rude to people asking them about it. It got so bad that in February 2014, Google published a list of dos and don’ts for using Glass, directly addressing user behavior and instructing people to not “be creepy or rude (aka a ‘Glasshole’)” and to “Respect others’ privacy, and if they have questions about Glass, don’t get snappy.”[28]

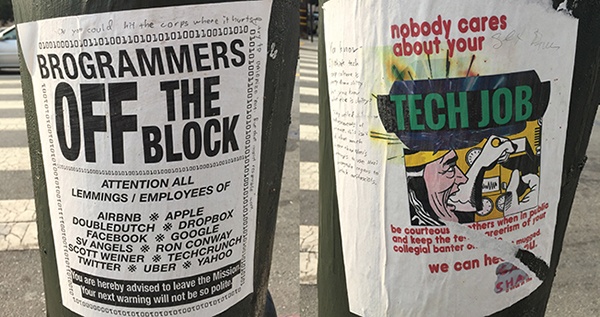

Nobody wants you filming them all the time, and I get that, but there were bigger issues at play than etiquette. Though the violence in San Francisco involved people using Glass, the attacks weren’t about the device itself, they were about the growing frustration with the tech industry and gentrification (see Figure 4-12), a problem that existed well before and after the Glass. The attackers didn’t yell, “Stop recording me.” They yelled, “F Google.” The Mission attack was right after an anti-Google protest in the neighborhood; the device was merely a symbol. Even though the attacks were more about San Francisco’s wealth inequality problems than the device, the attacks were even more negative press for the device.

Not a Failure

On January 15, 2015, Google announced the end of the Explorer program and stopped making the devices available to the public. So, was Glass a failure? Yes and no. The device was absolutely not a failure, it’s a great piece of technology that is very useful (as we’ll see in Chapter 5) and had a lot of very smart people behind it. What we have to remember here is that Glass was never a commercially released product; it was a beta version, plain and simple. Where Glass did fail was how the company handled the launch and publicity of the Explorer program.

One of the only people from Google[x] to talk publicly about this failure was Astro Teller at the closing keynote of South by Southwest Interactive in 2015, two months after Google shut everything down. “We allowed and sometimes even encouraged too much attention for the program,” Teller admitted “Instead of people seeing the Explorer devices as learning devices, Glass began to be talked about as if it were a fully baked consumer product.” He went on to say “we learned a lot from the very loud public conversations about Glass and will put those learnings to use in the future. I can say that having experimented out in the open was painful at points, but it was still the right thing to do.”[29]

Pulling This All Together

Google’s Glass Experiment was a well-meaning attempt to build a truly wearable, multifunctional computer platform, and the company created an incredible device that was derailed by the greater social context of the technology industry and poor management of the public image of the device. This type of platform has been a dream of the wearable device community for a very long time and will definitely not go away. Though we might not be wearing Google Glass devices any time in the near future, there are certainly technologies that are coming online that will expand upon the general concept and will certainly achieve the goal of a truly wearable computer. We discuss these in Chapter 5.

[11] Morton L Heilig, Sensorama Simulator, US Patent US 3050870 A, filed January 10, 1961, and issued August 28, 1962.

[12] Ivan E Sutherland, “A Head-mounted Three Dimensional Display,” Proceedings of the December 9–11, 1968, Fall Joint Computer Conference, Part I on - AFIPS ‘68 (Fall, Part I), December 1968, 757–764. doi:10.1145/1476589.1476686.

[13] Steve Mann, “Smart Clothes: The MIT Wearable Computing Web Page,” last modified December 18, 1995. (http://www.wearcam.org/computing.html).

[14] Bradley J Rhodes and Thad Starner, “Remembrance Agent: A continuously running automated information retrieval system,” The Proceedings of The First International Conference on The Practical Application Of Intelligent Agents and Multi Agent Technology, 1996, 487–495 (http://alumni.media.mit.edu/~rhodes/Papers/remembrance.html).

[15] Alex Spiegel, and Lulu Miller, “Computer Or Human? + Thad,” Invisibilia, NPR, February 12, 2015 (http://www.npr.org/2015/02/13/385793862/computer-or-human-thad).

[16] Mark Billinghurst and Hayes Raffle, “The Glass Class: Designing Wearable Interfaces,” course taught at the CHI 2014 conference, Toronto, May 1, 2014.

[17] Clint Zeagler, Thad Starner, Tavenner Hall, and Maria Wong Sala, On You: A Story of Wearable Computing, Exhibit at the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA, June 30–Sept. 20, 2015.

[18] Clint Zeagler, Thad Starner, Tavenner Hall, and Maria Wong Sala, Meeting The Challenge: The Path Towards a Consumer Wearable Computer (Georgia Institute of Technology 2015).

[19] “Project Glass: One Day...” Google, Published on YouTube April 04, 2012 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9c6W4CCU9M4).

[20] “We think technology should work for you—to be there when you need it and get out of your way when you don’t,” Google Glass Blog, April 4, 2012 (https://plus.google.com/+GoogleGlass/posts/aKymsANgWBD).

[21] West Virginia. Legislature. House of Representatives. Committee on Roads and Transportation then the Judiciary. A BILL to amend and reenact §17C-14-15 of the Code of West Virginia, 1931, as amended, relating to traffic safety; specifically, establishing the offense of operating a motor vehicle using a wearable computer with a head-mounted display. H.B. 3057. 2013 Reg. Sess. (March 22, 2013).

[22] “Google Glasses BANNED,” The 5-Point Café, March 11, 2013 (http://the5pointcafe.com/google-glasses-banned).

[23] “Glass and Facial Recognition,” Google Glass Blog, May 31, 2013 (https://plus.google.com/u/0/+GoogleGlass/posts/fAe5vo4ZEcE).

[24] Sarah Slocum, “Google Glass Assault and Robbery at Molotov’s Bar, Haight St. February 22, 2014 (warning: profanity),” I Love Social Media:, March 21, 2014 (http://ilovesocialmediainc.blogspot.com/2014/03/google-glass-assault-and-robbery-at.html).

[25] Adario Strange, “Another Google Glass Wearer Attacked in San Francisco,” Mashable, April 13, 2014 (http://mashable.com/2014/04/13/google-glass-wearer-attacked/#IUBoJNXakPqX).

[26] Kia Makarechi, “Google Glass Wearer Robbed at Taser Point,” Vanity Fair, April 16, 2014 (http://www.vanityfair.com/news/tech/2014/04/google-glass-wearer-robbed-at-taser-point).

[27] Rainer Schönhammer, “The Walkman and the Primary World of the Senses,” Phenomenology + Pedagogy 7 (1989): 127–144.

[28] “Glass Explorers,” Glass Press, February 15, 2014 (https://sites.google.com/site/glasscomms/glass-explorers).

[29] Astro Teller, “Moonshots and Reality,” Speech, South By Southwest, Austin, March 17, 2015 (https://youtu.be/3e0c0rL00bg).

Get Designing for Wearables now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.