Most Google searches help you find text and pictures on pages anywhere on the Web. But two Google services, Groups and Answers, are actually sites hosted by Google, and they primarily help you connect with other people by providing forums for online conversations.

Google Groups lets you participate in or search through the archives of Web-based discussion groups—and if you find the conversations boring, you can even start your own discussion group and invite people all over the world to join you. Google Answers can help you bypass the discussions and find expert research on nearly every subject known to humankind.

Both services have a cyber-community feel, and this chapter reveals how to participate or how to read along without posting a peep yourself.

Back before the Web, when dinosaurs like the Commodore 64 roamed the Earth, the Internet had a cousin called Usenet. Like the Internet, Usenet was a decentralized global network of computers. But unlike the Internet, Usenet was designed solely to carry the traffic of a massive collection of text-based discussions, or newsgroups. The groups were organized by topic, and anyone could jump in at any time (the messages stayed online, like a bulletin board, as opposed to a live chat). Hundreds of thousands of people participated in newsgroups, making Usenet one of the first popular systems for online communication.

More than 20,000 groups are still active today, and about 100,000 have archives, covering everything from Abraham Lincoln to Intel microprocessors to organic chemistry to civic issues in Winnipeg. And most of the messages in Usenet—also called posts, postings, or articles—are saved in perpetuity, making it a rich source of information, and history, too.

Note

Usenet has had a role in the evolution of English: A number of terms that are widely used today, like spam and FAQ, first appeared in newsgroups.

Since 2001, Google has hosted Usenet newsgroups under the name Google Groups (see the box in Section 4.1.1). By the end of 2004, Google had overhauled Groups with a redesigned interface and added tools to let users easily create fresh new discussions. The company also gave the whole enterprise a speed boost; new postings to the boards now pop in about 10 seconds and are indexed within 10 minutes. Google Groups includes thousands of live groups, plus Usenet archives since 1981, totaling a billion messages—and counting.

The biggest advantage is that, as part of Google, the groups and their archives now appear as Web pages with the power of a Google search built right in. So you can look up information by keyword, by date, or by author, and you’re bound to find something juicy every time you dive in. And, of course, you can jump into the fray and post messages for discussion, too.

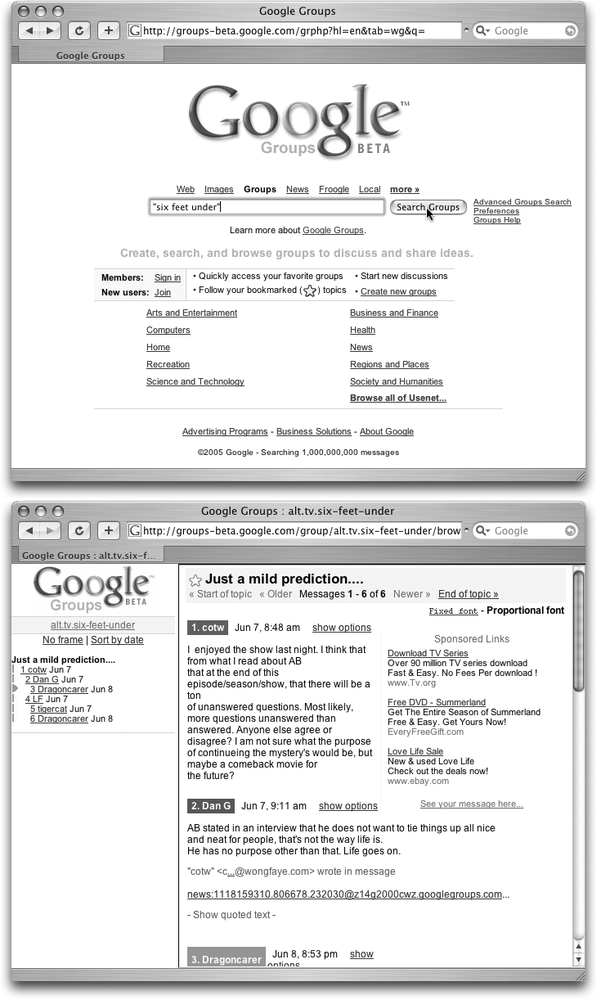

Figure 4-1 shows you the front page of Google Groups (http://groups.google.com/), which is similar to the Google Directory (Section 3.4) in that it lets you either browse by topic or run a keyword search.

Groups are handy for finding arcane bits of knowledge (how to use an old Atari console as a Web server), for connecting with people who share an interest of yours (Renaissance cat paintings), or for talking to an expert who might be able to answer a question (where can you get the best tuna on rye in Dubuque?).

Even better, while a regular Web search doesn’t let you target the date a page was created, a search in Google Groups might yield gold because you can specify results from any day or range of days from May 12, 1981, to the present. Groups are thus a good place to find out what people are thinking about today’s news (Jennifer Aniston: hot or not?) and yesterday’s news (Valerie Bertinelli: hot or not?)

If you need tech support, consider heading over to Groups, where you can search existing messages for help, and post questions and answers. In fact, the archives and regular participants in many groups have become a primary technical support system for lots of software programs. But even if the software you use has more formal help systems, groups can be quicker (nothing beats a successful keyword search), cheaper (free), and more thorough (other people can be surprisingly willing to help you through a difficult problem, and you can get assistance from several people at once). Microsoft alone has nearly 300 Usenet groups in the hierarchy microsoft.public.

Figure 4-1. Top: As part of its new design, the Google Groups home page has replaced the dotty old Usenet system of organization with friendlier categories. The old Usenet system is still around and accessible in the “Browse all of Usenet” link, where you can stroll down Internet memory lane and still find the old chestnuts like alt.tv.dinosaurs.barney. die.die.die. Bottom: A discussion on alt.tv.six-feet-under. Usenet groups like this one are still loud and proud, but there are plenty of newer discussion groups that have sprung up since Google gave Groups a face-lift. Like many Google services, a strip of Sponsored Links (Section 1.4.2.1) adorns the right side of the page.

Tip

You can often find groups that discuss software from defunct companies or outdated programs—a real boon when you can’t figure out how to print in dBaseII.

Newsgroups are also known for providing a sense of community on the Internet. If you like connecting with other people around a common interest, be it vermiculture or vintage porn, you can find a clique in Google Groups—or start your own club (the box in Section 4.1.6 gives some examples of why you might want to). Many Usenet groups have active participants who’ve known each other electronically for years (Section 4.1.1 tells you how to figure out which those are, but in general, the Alt section of Usenet has the most gregarious groups), and you can start new groups, too (http://groups.google.com/googlegroups/help.html#added tells you how to request a new group).

Back in Ye Olde Days of Newsgroupes, the way the messages and responses were displayed looked kind of like a trippy email/Web hybrid, which could be confusing. With New Improved Google Groups, however, user-interface experts obviously had their say in redesigning the service with a cleaner, less cluttered look. You have your choice of an easy-on-the-eyes proportional font (each letter takes up a different amount of space, which helps your brain recognize them) or an old-fashioned fixed font (each letter is the same width) to display the onscreen text. The old-style Usenet look is still available if you opt for “tree” view, but newcomers may prefer the standard, more straightforward design. The next few sections will get you surfing any style of group like a pro.

When Google revamped Groups, it added the power to create your own online discussion groups and invite as many or as few people as you want. Sure, the hearty old Usenet groups are still around (and explained starting in Section 4.1.3), but Google has moved its own version of Groups front and center.

Note

Google is still tinkering with the service and trying new things. So for now, Google Groups is still considered a beta project (that is, there might be some rough edges).

As you saw back in Figure 4-1, the Google Groups main page has a list of ten general categories, with dozens of subtopics contained within:

Arts and Entertainment. Movies, music, television, and entertainers are all in this category, as are arts-related discussions about technology, computers, education, and business.

Business and Finance. Here, you’ll find people talking about investing and financial markets, business and consulting issues, and financial news.

Computers. The geeks shall inherit this category, as everything from artificial intelligence to programming to systems and security are covered in the more than 8,000 different groups here.

Health. Addictions, alternative medicine, diseases, and medicine are here, along with topics like beauty and fitness.

Home. Martha Stewart would like this category, which contains discussions on cooking, gardening, shopping, home improvement, and so on.

News. You’ll find current events, breaking news, and gab on the latest developments in the world right here.

Recreation. Sporty subjects like camping, autos, and outdoor sports are here, along with groups devoted to animals, antiques, astrology, games, travel, and other leisurely pursuits.

Regions and Places. Want to find people talking about Newfoundland? This is the category for you. You’ll also find information on what to do in Marrakech and how to set up a business in Guatemala.

Science and Technology. All those subjects you either loved or hated in school—math, astronomy, biology, chemistry, physics, philosophy—are under discussion here, along with space, weather, agriculture, and other serious topics.

Society and Humanities. Items of cultural interest dominate this group, with areas devoted to education, activism, government, law, languages, religion, and more.

Once you click a category, the next screen presents you with all the topics within the category; keep clicking until you drill down to the group that interests you. You can also search specifically for groups that focus on topics you’re interested in, like ferret care or mandolin playing.

Note

Some Google Groups have restricted membership lists, while others allow anyone to join. The description on each group’s page gives the details.

Most categories include discussions centered on different geographical regions (Dungeons & Dragons in Ireland, for example) and in multiple foreign languages (boating in France—in French), along with the thousands of English-language groups.

The old-school Usenet groups are organized by categories, each of which has subcategories and sub-subcategories (and sometimes sub-sub-subcategories and beyond). Each topic has many discussions (also known as threads) associated with it, and each discussion is made up of one or more posts.

That’s easy enough, but newsgroups have a peculiar naming system. Top-level categories, like those listed on the Google Groups Usenet page (Figure 4-2), are called hierarchies. All newsgroups fit into a hierarchy, as indicated by first part of a group’s name. Subsequent parts of a name consist of subcategories and specific topics, and each part is separated by a period (dot). For example, the Sci (science) hierarchy has a subcategory called Agriculture, which has four separate topics: sci.agriculture.beekeeping, sci.agriculture.fruit, sci.agriculture.poultry, and sci.agriculture.ratites. In the beekeeping topic, a recent thread was called “Swarm prevention by foundation in the brood nest,” and it had ten posts.

Note

Usenet group names always have at least two parts—a hierarchy and a subcategory—and sometimes five or more (for example, alt.collecting.beanie-babies.discussion.moderated).

The Usenet area of Google Groups has more than 950 hierarchies listed, but here are ten of the most common:

Alt. This category’s name stands for “alternative,” but might as well mean “anything goes.” The topics are sometimes very specific (alt.animals.goats.pygmy), and the conversations are often freewheeling.

Biz. This category is supposed to have discussions about business products, services, and reviews. But there aren’t many groups in Biz, and the ones that are there typically aren’t very active. Not to worry: A lot of business topics are covered in other hierarchies.

Comp. Computers: hardware, software, operating systems, theory, and more, all in one place. Geek city.

Humanities. In theory, this hierarchy covers fine art, literature, philosophy, culture, and other liberal-artsy topics. In practice, nearly all that stuff is discussed much more actively in Alt and Rec. Humanities has a few active groups, however, including humanities.classics, humanities.lit.authors.Shakespeare, and humanities.philosophy.objectivism.

Misc. This category is supposed to cover the miscellaneous—which is odd, because most Usenet hierarchies carry pretty random groups. Notably, Misc contains some employment and for-sale groups, plus misc.kids, misc.health, and misc.immigration.

News. This hierarchy is all information about Usenet. (For current events, see the Talk hierarchy.)

Rec. This hierarchy covers recreation and entertainment, including arts, aviation, food, games, hobbies, humor, knives, music, outdoors, sports, travel, and so on.

Sci. Here you’ll find science of all kinds: aeronautic, cognitive, cryonic, environmental, linguistic, and physical, just to name a few. You’ll also find larger discussions of science, like sci.skeptics.

Soc. Social issues. A few groups here get lots of activity, including soc.geneology, soc.culture (which covers countries, like soc.culture.afghanistan and soc.culture.yugoslavia), soc.history, and soc.religion.

Talk. Current issues, especially those that lend themselves to controversy and debate, go here. Politics and religions are hot. Talk.meow, however, appears defunct.

Tip

Alt is by far the largest hierarchy, with thousands of groups. The rest have only a few hundred—or fewer—groups.

In addition to the ten main hierarchies, Usenet has a slew of more specific hierarchies, covering regions (everywhere from Alabama to York), companies (Microsoft alone has set up hundreds of groups that discuss its products and provide forums for technical support), computer languages and products (Perl, Debian), and organizations (Navy, Yale, you name it). To see them all, pull on your Internet hip waders and click the link on the Google Groups home page for “Browse all of Usenet”.

Note

When you see an asterisk in a group name, you’ve found a group that has multiple subcategories or subgroups. For example, Microsoft.* means that the Microsoft hierarchy has multiple subcategories, Microsoft.public.* means that Microsoft.public has several subgroups, and so on.

The asterisk is a wildcard (Section 1.3), and this is the one place on Google where a wildcard can be attached to other words.

You can find things in Google Groups by searching for words that you type in the Google Groups search box (just like a regular Google search) or by browsing through the categories until you hit a discussion you want to read. If you want to find something specific, or if you want to find out which groups discuss a particular topic, your best bet is to run a keyword search.

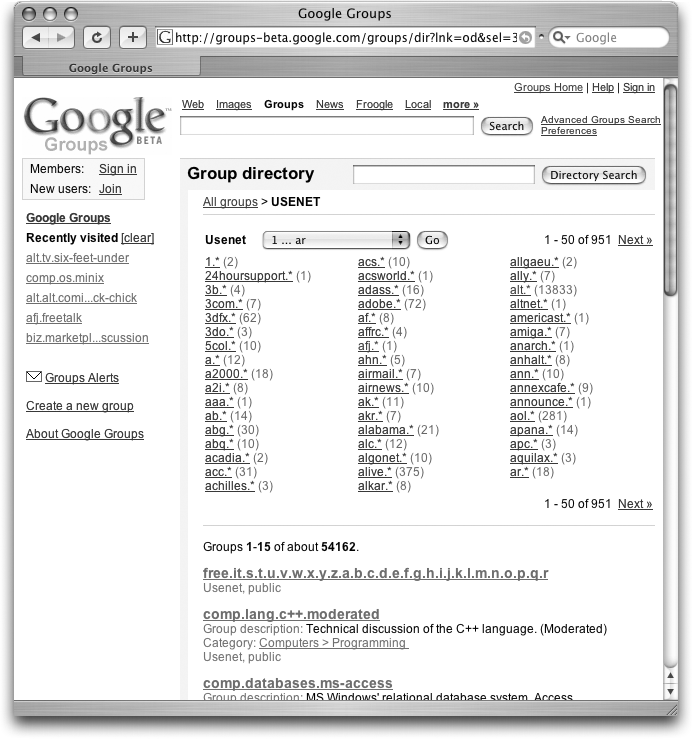

To browse Google Groups, start on the main page and click either a category link or the “Browse complete list of groups” link. Either way, Google takes you to a list of groups, like the one shown at top in Figure 4-3. From there, you can click a subcategory and a sub-subcategory (and so on) until you get to a thread you want to read.

Figure 4-3. Top: When you opt to browse all of Usenet from the Google Groups home page, you can wander through the hierarchies until you find one that suits your fancy. If you’ve clicked on “rec.” on your Usenet travels, you wind up here—a complete, alphabetical listing of groups in the Rec hierarchy. You can see the rest of the list by clicking Next in the bottom-right corner. To dig deeper, click a group name. Middle: Clicking a group name brings you to the subgroup page. In this case, it’s all the subgroups under rec.aviation that explore a topic within aviation. Bottom: Clicking a sub-subgroup name takes you to a page that has nothing but threads (rec.aviation.student).

On any page listing groups, the gray/green bar under some group names tells you how popular that group is. The greener the bar, the more members belong to the group. Usenet groups, all open to the public, typically have huge memberships; unfortunately, some boards have become vast wastelands of spam. If a group name has an asterisk and a number next to it—for example, rec.aviation.* (23)—Google is telling you how many subgroups the group has.

Tip

You can jump around the levels of a hierarchy by using the path at the top of the page next to the search box. The path tells you where you are now (for instance, Group: rec.aviation.student), and each part of the name is a link that takes you to the corresponding subgroup (click “rec.” to jump back to the full listing of Rec groups). If you click the Google Groups logo in the way-upper-left corner of any page, you wind up back on the Google Groups home page.

When you’re finally facing a list of threads (as shown at bottom in Figure 4-3), note that they’re posted in reverse chronological order, with the most recent at the top. In newsgroups, most recent means the thread that has the most recent message in it—not the thread that was started most recently. For example, if a thread started in 1993 but had a new post yesterday, it appears at the top of list—just below a thread that started today.

Like an email message that gets batted back and a forth, a thread retains the same subject title until somebody changes it (at which point it becomes a new thread). Thus, when you see a subject title (“Tejon pass questions”) followed by a number (“13 messages”), you know all those posts are on the same topic.

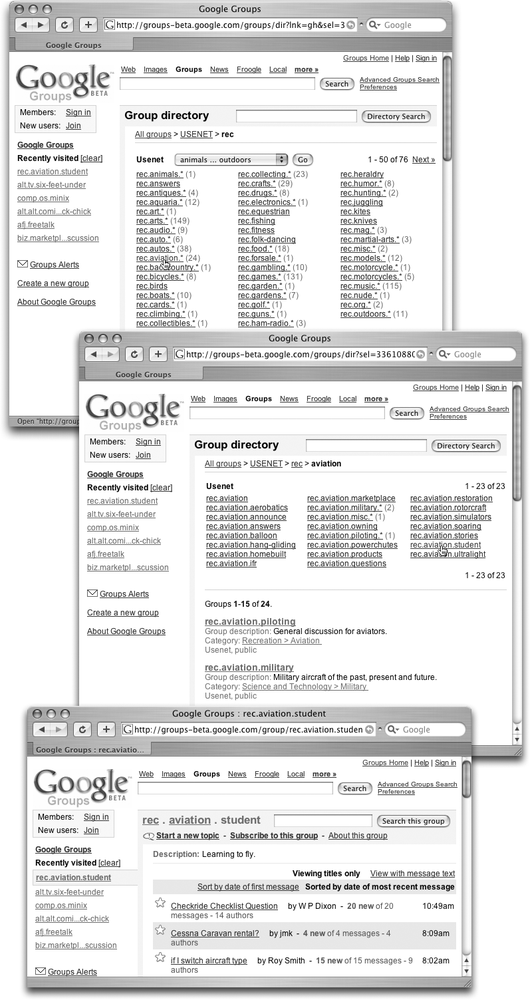

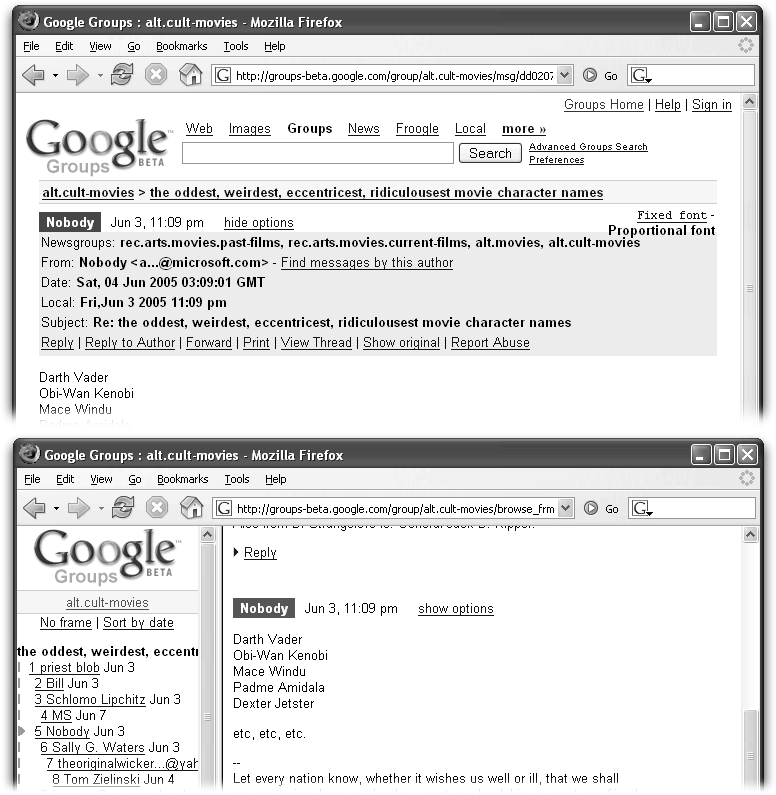

If you click a subject title, Google displays the most recent message in the thread, as shown in Figure 4-4. What’s confusing here is that Google shows the list of threads with the most recent activity at the top, but it shows the list of messages within a thread in the opposite manner: The most recent message is at the bottom of the list.

Although Google takes you directly to the last message—which is handy if you’re actively keeping up with a thread—it’s often more intuitive (and useful) to start reading at the top of a thread, especially if you’re new to a topic. To jump to the top, click the first name in the list on the left or click the “go to top” link on the right side of the page.

Tip

If you’re looking at a short thread, you can often just scroll up the main window to reach the first post.

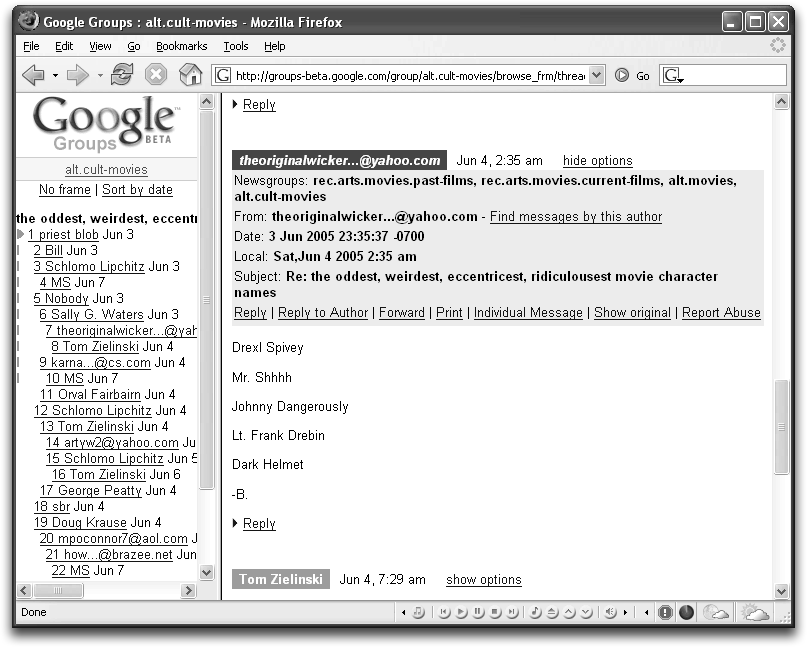

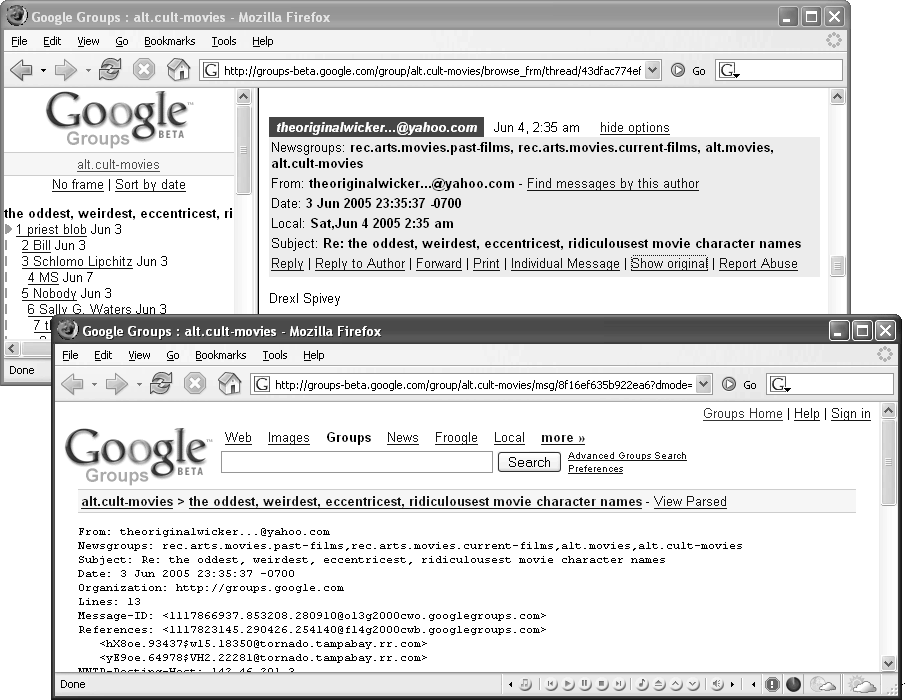

Each individual message has a few moving parts, as shown in Figure 4-5.

Because a newsgroup thread can contain a few subthreads, and because you can find and read messages individually (and therefore out of context), people posting to threads commonly include a snippet of the message they’re responding to. Quoted text appears in a different color and sometimes under a “Show quoted text” link that serves to tuck up the text so you can read down the threads faster.

Figure 4-4. The main window displays the actual messages in this thread. The pane on the left shows who posted a message and when; click a name, and you jump to that post. (If you don’t see the left pane, scroll up and click “No Frames”). The orange arrow indicates which message you’re currently looking at in the main window, and the orange lines above or below it tell you which posts appear if you scroll up or down the main window.

Figure 4-5. Top: If you click the “show options” link next to the colored block showing the author’s nickname, you’ll get choices to act on the message. In the gray header at the top of each message, you can find the name and email address of whoever posted the message (to see a list of all the messages that person has posted to Google Groups, click the name). You also get the subject title, a link back to the list of threads for that newsgroup, and the date and time the person posted the message. Bottom: Click the “Show original” link, and Google takes you to a page showing just this post—handy primarily if you want the post’s Message ID (Section 4.1.4.4), as this is the only place to find it.

Tip

If you find the left pane distracting, click “No frame.” You can always get it back by clicking “View as tree.” (just below the thread name).

If you have the left pane open, you can supposedly use the Back link like the Back button on your browser. But Google can lose track of your progress, so it’s usually better to stick with the familiar Back button.

That’s it for the ins and outs of browsing Google Groups—but because the system has a lot of odd corners, it can take a while to get comfortable clicking around. After a session or two, though, you’ll be zipping through messages like a pro.

Of course, a lot of the time, browsing can’t help you pinpoint a piece of information. For those times when you need to zero in on a query, you can run a search that looks for your keywords in all Google Groups, or you can search within a single hierarchy or any subcategory.

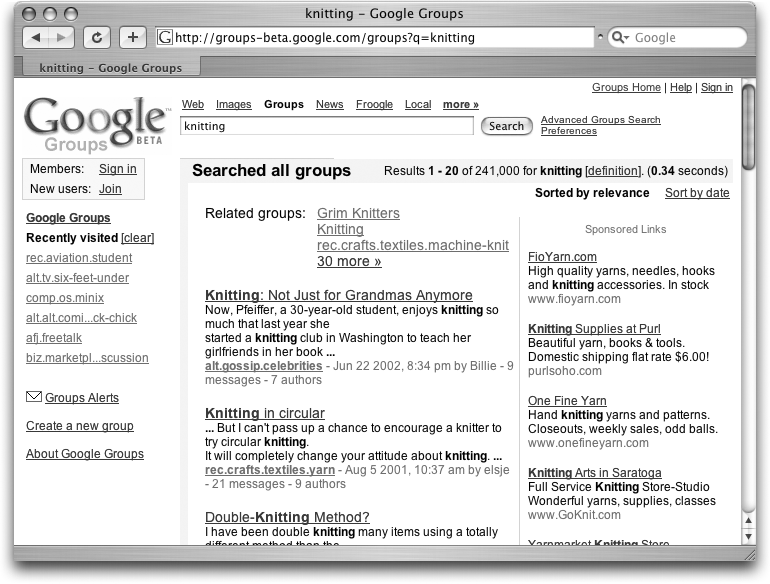

To search the whole newsgroups enchilada, simply type your query into the search box on the main groups page. As Figure 4-6 shows, a Google Groups results page looks a lot like a regular Google listing, with your results along the left and a few ads (Sponsored Links) along the right.

Figure 4-6. At the top of your listing are links for “Related groups,” which are newsgroups that Google thinks have something to do with your keywords. Click a link to jump to that group. Below that, Google shows you snippets from posts that contain your keywords. Each result is headed up by the title of that discussion (which is like the subject header in an email message), followed by the snippet, and then a line with a link to the group that contains the message, the date that message was posted, the user name of the person who posted it, and the option to view the whole thread that contains that post. If you click the title, Google takes you directly to that individual message.

Tip

Google Groups ignores stop words (Section 1.2.2) even when you put them in quotes. Thus, it reads "The Shining" the same as The Shining—which, since Google ignores “the,” is the same as Shining. If you want Google Groups to include a common word, you have to put a plus sign (+) before it, like this: +The Shining (remember, no space between the plus sign and the search term).

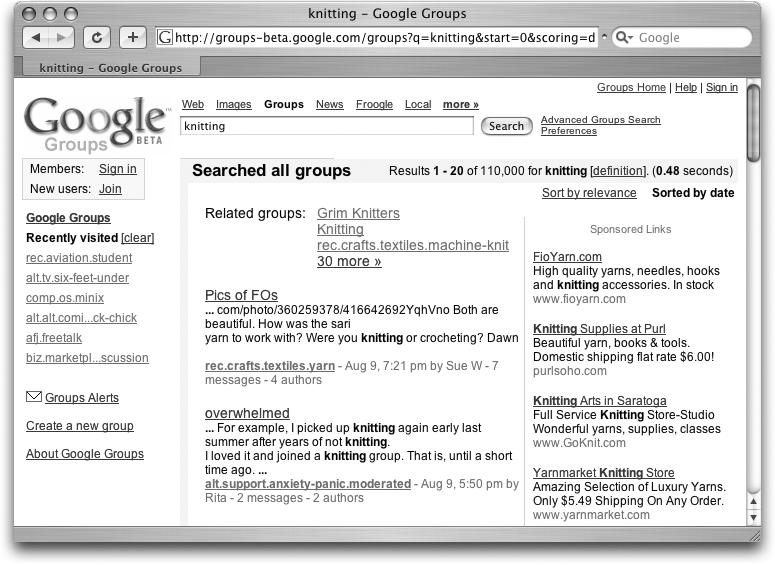

Unlike regular Google results, you can sort Google Groups results by date. That’s because when somebody posts a message to a newsgroup, the system automatically date-stamps it (the Web has no equivalent method for dating regular pages). Google normally shows groups results listed by relevance—just like regular results. But in many cases, sorting by date—which puts the most recent post at the top, followed by the most recent post before that, and so on—gives you much more useful listings.

For example, if you’re searching for a person or event that’s been in the news lately, sorting by date—which you can do by clicking the link in the upper-right corner—gives you the freshest messages first. Figure 4-7 shows you how big the difference can be.

Figure 4-7. These messages are more recent than those in Figure 4-6, which Google sorted by its own estimate of relevance. Sorting by date also gives you new related groups at the top of the listings. To return to the relevance sorting, just click “Sort by relevance.”

When you’ve found a snippet that intrigues you and you want to read the whole message, click the subject title to jump to a page that holds just the message with your search terms highlighted (Figure 4-8, top). If you click “show options” and then View Thread, Google takes you to a page that looks like the one at bottom in Figure 4-8.

Figure 4-8. Top: This view shows you the message alone. If you click View Thread just above the message body (click “show options” next to the poster’s name if you don’t see it), Google opens the left pane, showing who posted messages and when; the orange arrow shows you where your message fits on the thread. Bottom: If you want to see the rest of the messages in the thread, click “See this message in context” at the bottom of the screen (not shown here).

If you’re looking at an article in a thread that has no other posts, Google doesn’t give you the option to view the complete thread, because you’re already looking at it.

Note

When you look at a message on its own, the link in the upper-right corner (“show options” → “Show original”) shows you the message with no formatting, which is handy if you want to cut and paste it into an email or other document. The original format also lets you see the header with the routing information, which is handy if you’re a geek.

A weird quirk of newsgroup results is that Google shows you up to only four links in the Related Groups listings at the top of the page. A lot of the time, you can tell that you’re not getting the whole picture—which is a drag if you’re trying to find the groups that cover your topic. For example, if you search for information on Condoleezza Rice, it’s pretty unlikely that the group with the most to say about Condi—in one such search—is alt.fan.art-bell (Art Bell is a talk show host). Where are the Republican or Democrat groups? Why don’t you see talk.politics?

A good trick here is to search within the hierarchies and second-level categories in your results. For example, searching for Condoleezza Rice in Alt or Soc—or, better yet, in alt.fan, alt.politics, soc.culture, and so forth—gives you good results (including additional related groups).

You can limit your search to a particular hierarchy, group, or subgroup in a few ways:

Using syntax. Remember Google’s special operators from Chapter 2? A few of them work here. You also have a new one at your disposal—group—which you can use to specify any area of Google Groups. Use it like this (with no space on either side of the colon):

condoleezza rice group:alt.*

or:

condoleezza rice group:soc.culture.*

or:

condoleezza rice group:talk.politics.misc

In the first two examples, the asterisk tells Google to look in any subgroup, subsubgroup, and so on, within that hierarchy or subcategory. In the last example, the query tells Google to look only in the group talk.politics.misc, since there’s no asterisk.

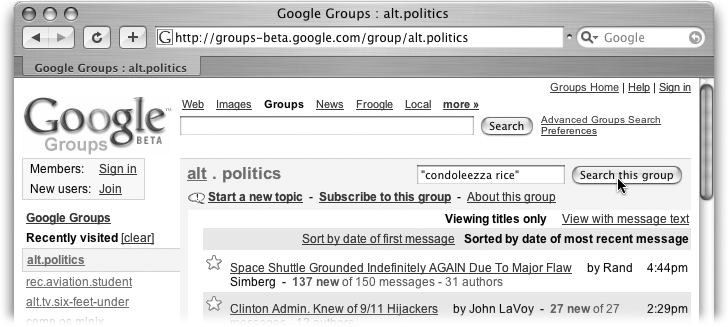

Using a category-specific search box. As explained in the earlier section on browsing Google Groups, you can navigate to a page for each category and subcategory. For example, if you’re on the Google Groups home page and you click “alt.”, you wind up on a page listing all the Alt groups. Similarly, if you click through to alt.politics, you get a listing of all those subgroups. If you click a link, as shown in Figure 4-9, the search box changes to look only within this group.

Using the Advanced Groups Search form. Just like the Advanced Search for a regular Google query, Google Groups has its own Advanced Search page. See the next section for a full rundown.

Warning

Occasionally, group names are misspelled. There is, for example, a group called alt.poltics.* You might land in a misspelled group without realizing it and miss valuable discussions in the properly spelled group (alt.politics.socialism.democratic is more active than alt.poltics.socialism.democratic).

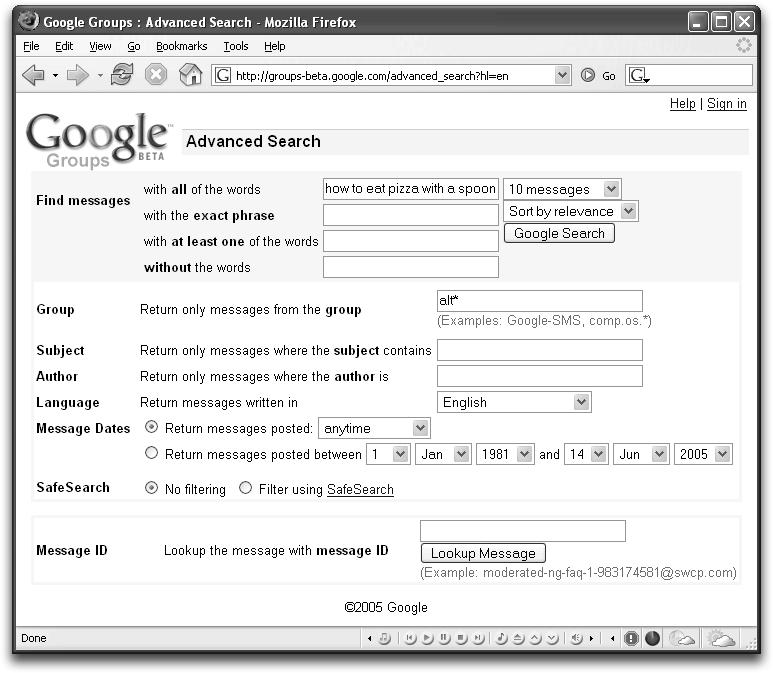

Almost every Google Groups page has a link that takes you to the Advanced Groups Search form (shown in Figure 4-10), which lets you narrow down your search in a number of useful ways, including by date (or date range), by language of the post, and by author. This form is particularly handy for mixing and matching elements—like looking for messages by one author in a single hierarchy before May 1, 2003.

Figure 4-10. When you jump to the Advanced Groups Search from a page of results, Google transfers your original search settings to the form. Thus, if you searched for how to eat pizza with a spoon in group alt.*, and you click from your results directly to the Advanced Search page, the form comes up with “how to eat pizza with a spoon” in the “with all of the words” slot, and “alt.*” in the Newsgroup slot. Here’s your opportunity to clear any settings you don’t want, and to add new ones.

By now, you’re probably familiar with the first four options, all of which let you choose the way Google treats your search terms (for a refresher, see Section 2.2). To the right of the top search box, a pop-up menu lets you decide how many results appear on a page. Below that, you can choose to sort by relevance or sort by date (either way, you can re-sort your listings from the results page).

In the next section, you can choose:

Newsgroup. This slot is just like the group operator described above. Use it to limit your search to a particular hierarchy, subcategory, or group.

Subject. The subject refers to the title of a thread. Use this when you want to restrict your search to one discussion or when you want to find a discussion on a particular topic.

Author. Every post has a “From” line (like email) that lists a name and email address. If you want to find all the messages posted by somebody you know, or somebody whose articles you admire, this is the field to use. Type a name, an email address, or part of either:

Curiousgeorge

or:

George

or:

george@whitehouse.gov

Bear in mind that posters often use nicknames and fake email addresses, both to protect their privacy and to prevent spammers from adding them to mailing lists. You can, of course, still search by author, but you can’t always find out a poster’s real identity or how to reach the person directly.

Language. The place to tell Google what language you want the messages in your results to be in. This option doesn’t translate messages; it just specifies which, if any, languages to restrict your search to.

Message Dates. Here’s where newsgroups really shine. The first menu lets you search for messages posted anytime, within the past 24 hours, the past week, month, three months, six months, or year. This is a quick way to find the freshest posts. But if you want to search for messages posted on a particular day, or a within a range of days (anytime from May 12, 1981, until today), you can use the second set of menus to get really specific. This awesome feature is lacking on most of the Web, making newsgroups the ideal place to find ideas and comments from a specific time period.

SafeSearch. Although it’s usually smart to keep SafeSearch turned off (Section 2.1.2), it can be handy for filtering out the waves of sexually explicit spam that plague a lot of newsgroups. Use it with caution, and keep in mind that it doesn’t block other potentially objectionable posts.

Message ID. When somebody posts a message, the system automatically assigns it a unique Message ID. Most of the time, you can ignore this field. But if somebody tells you the ID for a particular post—which happens occasionally with historic articles—you can zoom in on that single message.

For example, Linus Torvalds, the inventor of the Linux operating system, first announced his creation on Usenet in 1991. The message is legendary, and you can find it by searching for the Message ID 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. (Figure 4-5 tells you how to find any other post’s Message ID.)

Posting messages on Google Groups is a snap. The first time you do it, Google asks you to register with a user name and email address; after that, you’re free to shout out to the world. In fact, Google Groups reach people all over the planet, and a lot of those people believe in following Usenet etiquette—a set of posting guidelines that help keep electronic conversation flowing smoothly. People who violate the rules are not looked upon with kindness—even newsgroup neophytes (known as newbies). That doesn’t mean fresh faces aren’t encouraged; they are, and you should feel free to post up a storm. But before you dive in, familiarize yourself with the newsgroups’ style of exchange by reading a bunch of threads and checking Google’s dos and don’ts of posting messages (http://groups.google.com/googlegroups/posting_style.html). Google also has a Posting FAQ that’s worth three minutes of your time: http://groups.google.com/googlegroups/posting_faq.html.

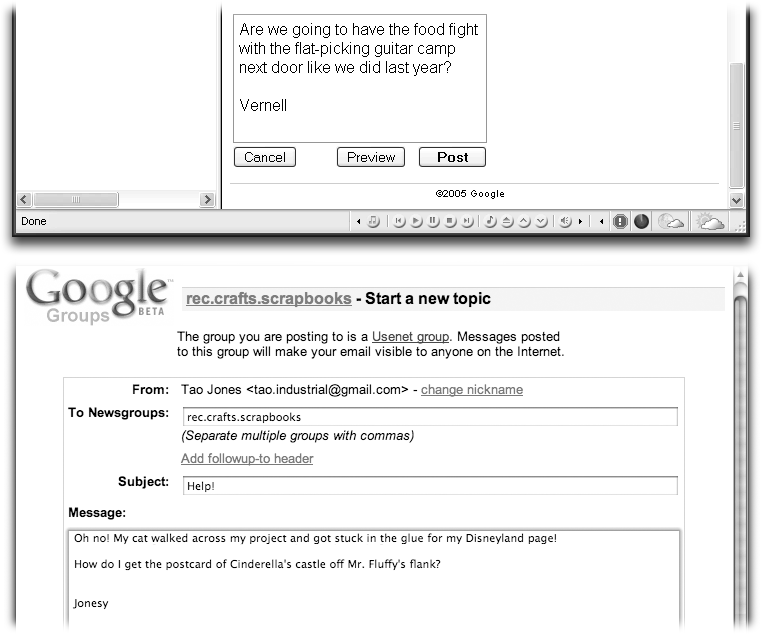

If you want to reply to an existing message, find the bottom of that message and click Reply (the link disappears if the message is more than a month old). A box unfolds on the page so you can type your response to the message. Click Preview to see what your polished prose will look like on screen, and then click Post to share your views with the world—or at least, the folks in this newsgroup.

Tip

You can follow up on a message that’s more than a month old—and thus has lost its Reply link. Simply post a new message in that group and use the same subject line as the thread you want to add to. Google appends it to the existing discussion under that name.

Many groups required you to “join” up by clicking a button on the page to add your name to the roster before you can post, so don’t be shy. When you join a Google-created group (as opposed to a Usenet group), you have the option of participating via email if you don’t want to check in on the Web. As you join different groups, a list of your subscriptions appears when you go to the Google Groups home page and log in.

If you want to start a new thread, navigate to the main page of the group you want to post in, and click “Start a new topic.” In either case, Google opens a page, shown in Figure 4-11, that lets you specify or change the header, write out your message, and preview or post it directly. If you reply to an existing message, Google copies that message into the “Your message” box; you can delete any of that text as you see fit.

Figure 4-11. Top: If you’ve used any HTML code in your message to, say, bold some text or add color, the “Preview” button lets you see what it will look like when you post it live. Bottom: When you click the “Start a new topic” link on a group’s main page, you have a clean slate and a clear shot to get your very own thread spinning.

Tip

When browsing the Google Groups you belong to, you can tag certain threads that interest you with little yellow stars so they stand out from the other kinds of text filling the screen. There’s also a “Show my Starred topics” link on the left side of the page that lets you cut right to the conversational chase.

Gmail (Chapter 11) is another Google service that lets you see stars. There, you can use the five-point beacons to highlight your favorite mail message topics as well.

In a nod to privacy (and lack thereof on the Internet these days), Google Groups slaps a mask over your email address so the spambots slithering around the Web can’t harvest it for nefarious purposes. Your address doesn’t get the mask, however, if you post to a Usenet group (which are hosted on servers around the world, including some used by spammers themselves), or if you participate in a group by email instead of using the Web interface. Snagging an email address just to use for posting (say, a Gmail address, which you can read about in Section 11.1) can help separate your Group mail from your other correspondence.

Once you click “Post message” it takes about 10 seconds for it to appear in Google Groups, compared to the hours it could take for the poor thing to show up before Google revamped the service. If you have a sudden change of heart and you want to remove your message, the Posting FAQ tells you how to do it (http://groups.google.com/googlegroups/posting_faq.html).

Before Google gave Groups a makeover, you could post to existing newsgroups, many of which were unwieldy or full of spam and trolls (those aggravating message-board members who like to pick fights in public forums) or not exactly the topic you were looking for. Nowadays, though, you can create your very own group on any topic you can think of. You can make it wide open for anybody in the world to join, or restrict the membership to just you and your pals.

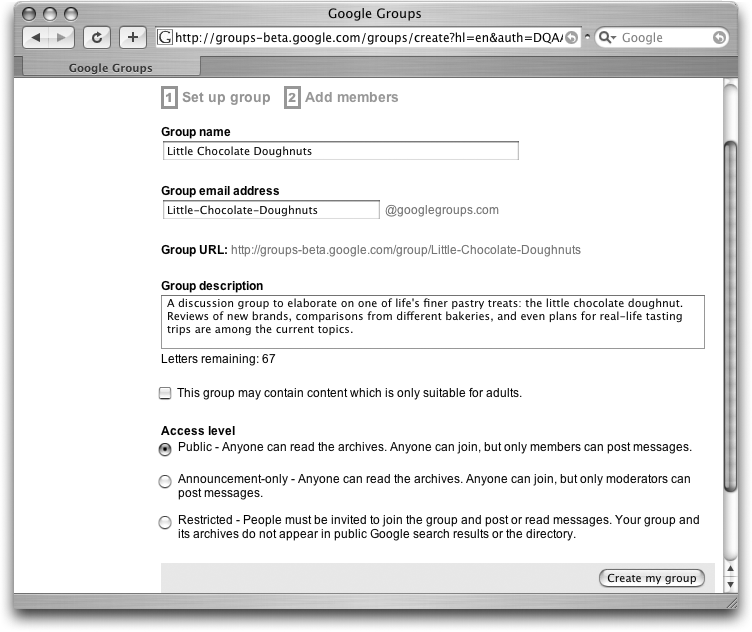

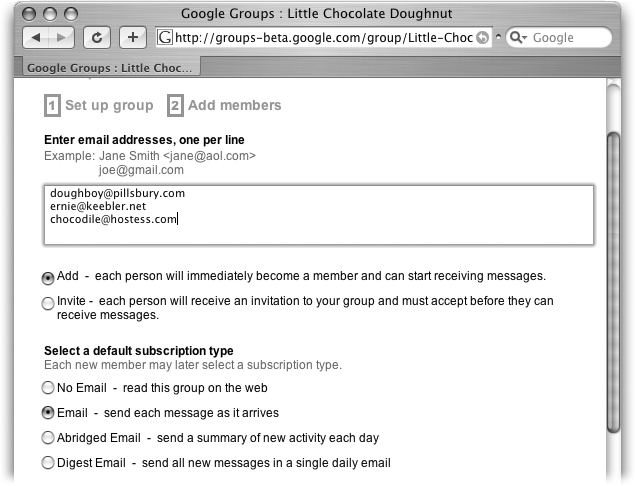

Creating your own group is as easy as clicking the “Create new groups” link on the main Google Groups page. It’s a simple two-screen process:

Give your group a name.

As shown in Figure 4-12, you need to give your group a name so people can find it. The page automatically fills in a similar email address on the next line that your members can use to post messages. Based on the name, Google also generates a URL for the group’s Web page, and you have the chance to type in a short description of what your group’s all about. If you plan to discuss topics off-limits to children, turn on the checkbox below the group description so your page will display an adult-content warning.

In the last section, you can set the access level for your group: Public (open to everyone to join and post), Announcement-only (anyone can join and read, but only the creator can post messages), and Restricted (invite-only to join and read, plus your group’s archived posts don’t appear in Google search results). Click the “Create my group” button to continue.

Add some people to your group.

Here, as shown in Figure 4-13, you can add the email addresses of friends and colleagues you’d like to join your online social circle. After you add their email addresses, you can decide how they can join (immediate membership from the get-go or a membership requiring a response to your initial invitation email) and in what form their messages initially appear (just on the Web site or by various email delivery methods). Add a welcome message, and you’re done!

Figure 4-12. Starting a group means giving it a name and an address so people can find it. You need to decide how people can join and participate as well.

Figure 4-13. Once you create your group, fill out the guest list of email addresses for those joining you and set a delivery option for the messages that get posted to your group.

Google sends a long email to your account with information about your group and links for articles on managing your new group. Google Groups has an elaborate Help section covering all the ins and outs of group ownership and management at groups-beta.google.com/support.

Google Answers may be the most underused corner of the entire site. But that doesn’t mean you have to miss out on this incredibly useful tool. If you’ve tried searching for something and all you’ve got to show for your work is eye fatigue, or if you simply don’t have time to seek out a piece of information, Google Answers (http://answers.google.com) may be your knight in electronic armor. The service lets you ask questions that real, actual people answer—for a fee. The people are research experts, and you set the fee, based on how much you’re willing to pay— anywhere from $2 to $200—plus a 50-cent listing charge. If you’re not satisfied with your answer, you can apply for a refund.

Without a doubt, the service sounds a little weird. Why pay strangers to look up things you could probably find yourself, gratis? Of course, you can use the service as a super-fancy search feature. But it’s better to think of it like hiring a research assistant, or having access to more than 500 friends with expertise in a range of topics. The people who work for Google Answers aren’t simply good at using Google’s Advanced Search form to find obscure Web sites and references. They’re seasoned researchers who can answer complex questions methodically, thoroughly, and clearly. There’s no better proof than their existing answers, which you can browse through or search from the Google Answers home page.

Note

Questions and answers appear publicly (though everyone who posts or answers a question gets a Google Answers screen name, so the system keeps people’s actual names private). Whether you have any interest in using the service or not, the answers are fun to peruse.

For example, a first-time writer working on a musical that he wanted to get produced recently asked: “What are the best theaters around the Seattle area to contact about developing the musical and putting it onstage? Any venues that are particularly friendly to newbies who are enthusiastic though inexperienced? At a minimum, what do you need to shop a musical around?” He offered $20 for the answer.

An hour and a half later, a Google Answers researcher posted a well-written 1,400-word reply (that’s about three single-spaced pages in Word) answering each part of the question with specific details, examples, and advice. The researcher also listed, as many do, the sources of the information—in this case, “personal knowledge and experience,” plus The Dramatists Sourcebook and some phone directories. (To see the question and answer, search Google Answers for Question ID: 327256.) A week later, another researcher chimed in—for free—with two additional suggestions.

That’s not necessarily the kind of information you could find in one and a half hours on your own—or by asking around among your friends. Nor are you limited to asking questions about musicals. Recent queries have included:

“How is the value of a bond determined? What is the value of 1-year, $1,000 par value bond with a ten percent annual coupon if its required rate of return is 10%?” (Question ID: 330297.)

“Is it true that the real Goth followers sleep in coffins?” (Question ID: 324406.)

“Is membership in private clubs [such as golf or yacht clubs] generally declining or increasing?” (Question ID: 323385.)

“My 24-year-old gorgeous [daughter] could use a date to go with her to the Masters golf tournament in two weeks. She wants to meet a film or sports personality. There are several hundred people that would probably be golf nuts who would love to go. How do I contact such a person? Time is factor here. PS. A list of sports agents would be best.” (Question ID: 323706.)

“I have been diagnosed and am being treated with ‘Procrit’ for Sideroblastic Anemia. I have been told that this disease is a ‘Precursor’ possibly for Leukemia. Is there any validity to this statement?” (Question ID: 329758.)

“Can I curse police? According to the First Amendment we have the right to free speech but where is the line drawn when police are involved?” (Question ID: 330406.)

Tip

To read a bunch of questions that researchers particularly enjoyed answering, see Question ID: 204301.

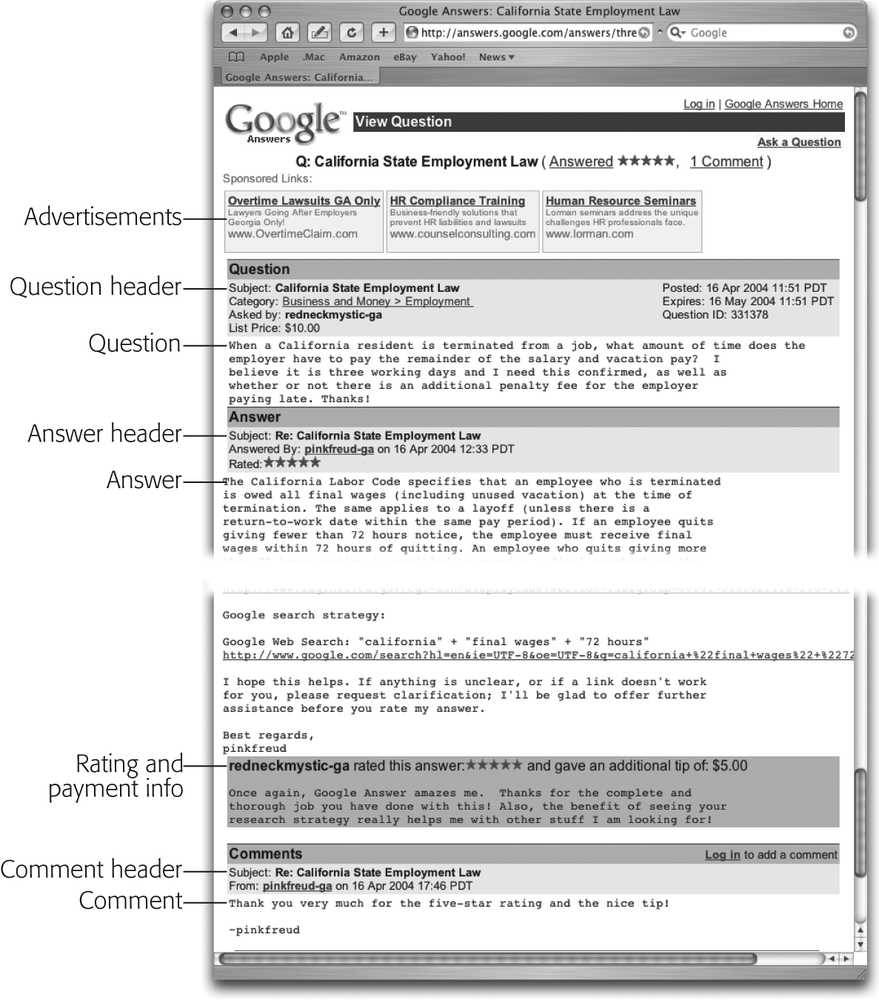

Figure 4-14 shows what a question and answer look like.

Figure 4-14. An answered question starts with a header supplying summary information about the post, including when it appeared (in Pacific Time) and its ID number (right side). Below that is the answer header, telling you who answered the question and when (in this case, about 45 minutes after somebody posted the question). The actual answer includes explanations, links to related resources, and, toward the bottom, the researcher’s search strategy. The lavender bar below that shows you how the asker rated the answer (five stars is best), whether he paid a tip (tips are optional, but outstanding answers often provoke generosity), and usually a note of thanks. At the bottom of the page are comments, which anyone can post and which sometimes include additional information.

And that’s just the tip of the inquiry iceberg. Since Google Answers began in April 2002, people have posed more than 300,000 questions on the site. Researchers pick the questions they want to answer, so not all questions draw a response. But of the questions that researchers do answer—more than half—most reply within a day, and many respond within a couple of hours.

Note

The questions that aren’t answered tend to be underpriced (say, $2.00 for a complete discussion, with citations, of the nature vs. nurture debate), inappropriate for the service (see the box in Section 4.2.2), or unclear (“What’s the best way to teach math?”).

Google Answers is a versatile service, letting you pose questions in categories like Arts and Entertainment, Business and Money, Family and Home, Health, and Science. While you can find similar categories in Google Groups, the information you can get on Google Answers is likely to be more relevant and of higher quality. (It’s also going to cost you, of course.) The service tends to be particularly useful for a few kinds of help:

Timely answers. You may be able to find an answer yourself. But if your afternoon includes attending your son’s soccer game, taking the dog to get her nails trimmed, negotiating the lease on your company’s office, and designing a new space shuttle, you might want to get somebody else to look into the best shape for wings. Many questions are answered within a few hours.

Research assistance. You remember seeing a Web site with tasty sauerkraut recipes, but you can’t find it anywhere. Google Answers can help you track it down.

Tip

Most researchers tell you how they found your answer (for example, the search terms they used), which can help you hone your own search skills by showing you how the experts seek information. In addition, if you were looking for something that required more than a Google query or two, most answers include links to the sites where they found your info, helping you learn where you can look for obscure stuff.

Embarrassing questions. Although you have to register for the service and create a screen name, your true identity is hidden—making Google Answers the perfect place to ask your question about octopus sex.

Market research. The service is a good place to get in-depth information on industries, products, and business processes.

Computer support. If you’re looking for help with a defunct product, or you were stymied by Microsoft’s Web site and don’t want to sit on hold for two hours waiting to speak with a tech support agent, you may be able to get a faster—and possibly cheaper—answer here.

Numbers and facts. You can get good value asking for statistics that are hard to find. Questions of fact about science, history, and notable people are also good candidates.

Background information on legal, financial, or medical issues. Google Answers does not give definitive advice in these areas, but researchers can steer you toward relevant resources and information.

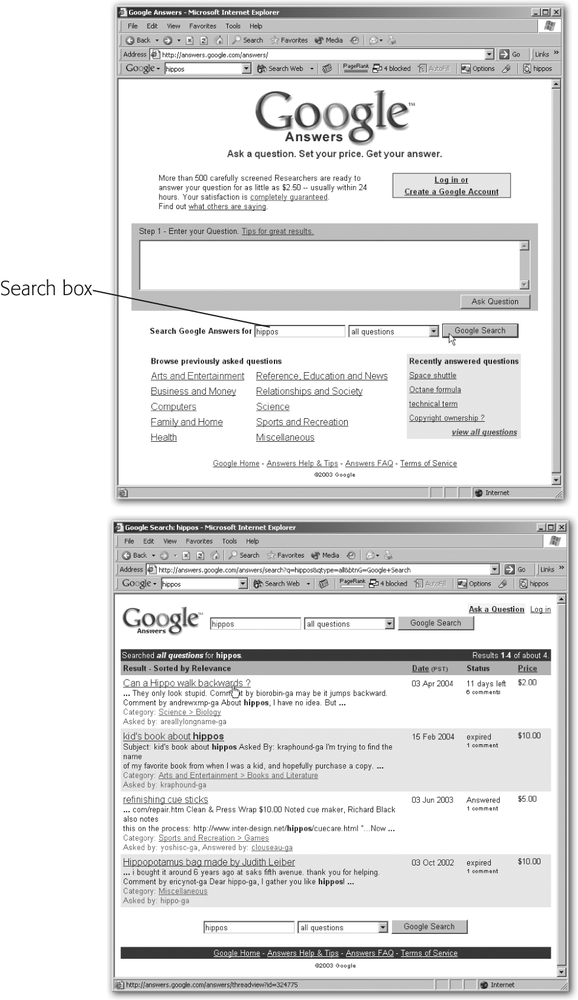

Wondering if hippos walk backwards? You’re not the first (Question ID: 324775). People have asked questions of every kind, so it’s worth looking around Google Answers to see if your problem already has a posted solution. It’s also a good idea to search the existing questions to get a sense of the going rate for your kind of question and to learn how to write an effective question (see Section 4.2.3 for more about question technique).

You can either run a keyword search or browse by category. (You don’t need a Google Answers account to search the site.)

You can run a keyword search from the box on the main Google Answers page (Figure 4-15), or you can browse by subject (explained in the next section) and then search within a category only.

Figure 4-15. Top: To run a keyword search, type your terms into the blank search box (not the question box, which is the big rectangle with the lavender outline). Use the menu to the right of the box to choose whether you want to search unanswered questions, answered questions, or both. Then press Enter or click Google Search to get a list of entries with your search terms. Bottom: Each result is a separate question. The first line of an entry is the subject (click it to jump to that whole question and answer), followed by a snippet from the question. Below that is the question’s category, then the screen name of the person who posed the question and the person who answered it, if there is one. On the right, you can see when the question was posed, whether anyone answered or commented on it, and how much the questioner was willing to pay for an answer.

Tip

When you want to find out whether anyone has ever asked for something specific, the tricky part is figuring out what they would have asked for. For example, if you’re looking for an elementary school classmate, you might benefit from what researchers told somebody looking for a tenth grade sweetheart. Try search terms that will get you a broad range of responses. Rather than searching for “how to find third grade friend,” try “people search.” If you get too many replies, you can always narrow down your results.

The keyword search is handy when you want to zero in on all the questions relating to, say, hippos. Because you can search by unanswered questions, it’s also a good way to learn the kinds of queries and prices that don’t draw any researchers. Conversely, searching answered questions gives you not only juicy hippo info, but a sense of how to phrase a question in order to get a useful answer and how much to pay for answers.

Google automatically sorts your results by relevance, or how closely each result matches your search terms. You can, however, sort by date or by price, either of which can be handy if you wind up with a long list of results and you want info from a particular time period or to compare prices. In the upper-right corner of your results listing, click the link for Date or Price. After you do, Google displays a little arrow next to the link, telling you whether your list is sorted in ascending or descending order. Click it again to sort in the other direction.

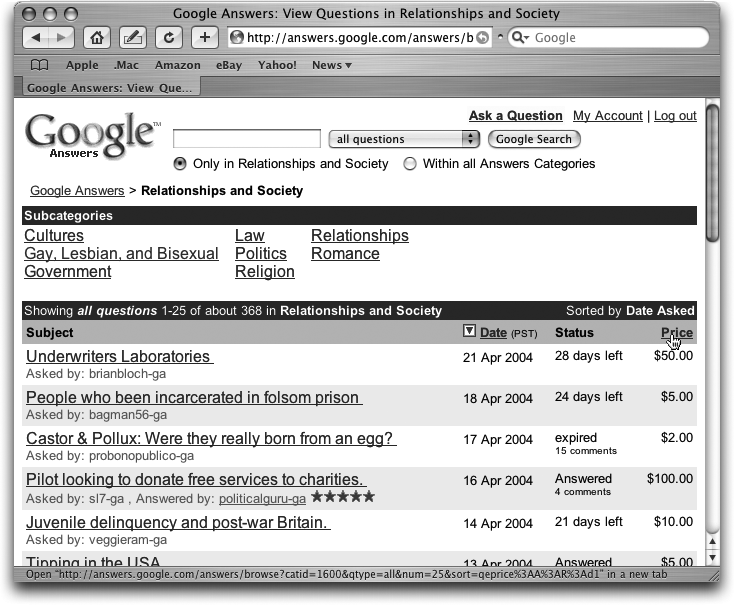

The other way you can find things on Google Answers is by browsing the categories, just the way you would sift through the Google Directory (Section 3.4). Start on the Google Answers main page and click a category to get a list of subcategories and results (Figure 4-16).

Figure 4-16. When you click the “Relationships and Society” link, Google shows you this page. At the top is a search box that lets you limit a keyword search to this category. Below that is a path showing you the page you’ve navigated to, followed by links for subcategories, and then a list of questions in the current category, sorted by date (most recent first). You can sort by oldest first—or by price—by clicking the links in the upper-right corner of the list. The bottom of the page has a link to take you to the next 25 results.

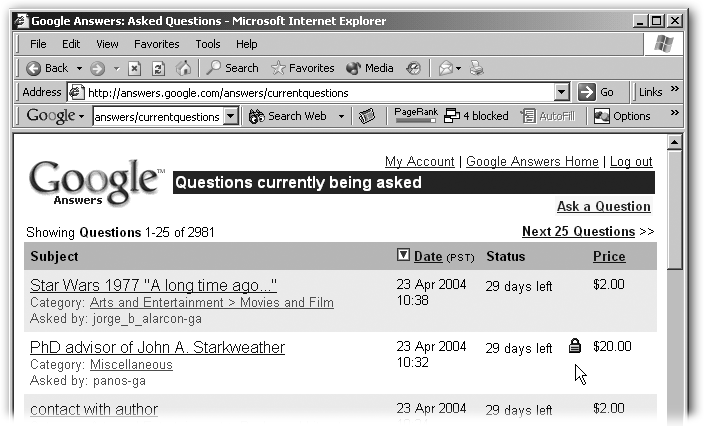

If you want to see the kinds of questions that are hot right now, you can browse all the questions asked in the last month. On the main Google Answers page, the box in the lower-right corner, “Recently answered questions,” has the four most recently answered questions and then a link to “view all questions.” If you click that link, Google takes you to page of results called “Questions currently being asked,” as shown in Figure 4-17.

In order to post a question, you need a free Google Account, which you already have if you’ve signed up to post messages in Google Groups (Section 4.1), or if you have a Gmail account (Section 11.1).

If you don’t have an account yet, go to the Google Answers home page and click “Log in or Create a Google Account,” then click “Sign up now” and fill in your email address and a password. Google sends you an email with a link to verify your account.

When you click that link, Google takes you to a Web page saying you’re verified. That page lets you click another link to an account page, where you can create a nickname that will appear onscreen whenever you post a question or comment in Google Answers (Google adds the tag “-ga” to every nickname). This page also asks whether you want to receive email from Google when somebody has answered or commented on a question you’ve posed. (If you choose not to get email, you have to keep an eye on your question to see if there’s been any action.) Finally, the account page asks you to read the terms of service and agree to them. Click “Create My Google Answers Account” to finish the process. (Google automatically logs you in.)

If you already have an account, you can log in either before you create a question or during the process. Here’s how to get questioning:

Come up with a good question.

This step may seem obvious, but a lot of questions go unanswered because the writer posed a confusing question or one inappropriate for the service (see the box in Section 4.2.2). Google gives tips on asking good questions, along with examples, at http://answers.google.com/answers/help.html.

In general, the more specific your question, the more likely you are to receive a satisfying answer—or any answer at all. For example, if you ask, “How do I get to Carnegie Hall?” the researchers have no way of knowing whether you’re looking for travel directions, career advice, or ticket information. Similarly, “Who’s the ninth U.S. Supreme Court judge?” doesn’t reveal whether you want to know the ninth justice ever, or whether you want to find out who the most recently confirmed justice was.

Tip

One of the best ways to be specific in your question is to explain what you’re not looking for. For example, “I’m staying at a hotel in New York, on the corner of Canal and West Broadway, and I want to walk to Carnegie Hall tonight. How do I get there? No subway, bus, or cab directions, please.”

You can also help researchers understand your question by explaining why you want a piece of information. If you’re looking for the going rate on rental castles in Spain, let them know if it’s for your honeymoon in July or because you’re thinking of renting out your own castle in Transylvania. The more detail you give, the more focused and relevant your answer will be.

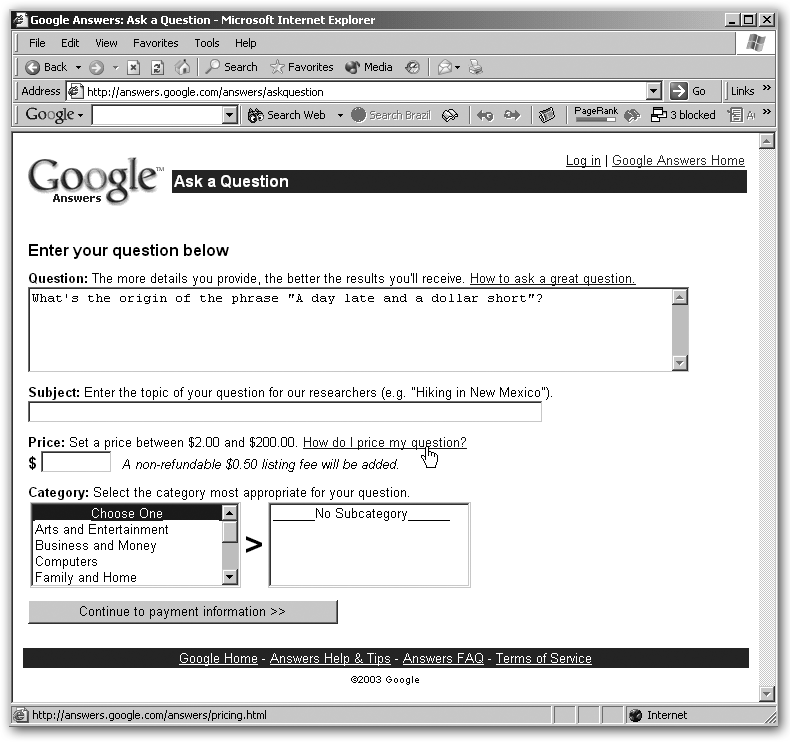

In the big box on the Google Answers home page, type your question, and then click Ask Question to jump to the page in Figure 4-18. Or, from any Google Answers page, click the link near the top, “Ask a Question” to get to the same page, and fill in your question there.

It doesn’t matter where you start, though; Google still takes you to the page shown in Figure 4-18.

Fill in the subject.

The subject is like the subject line on an email: It should give your reader a sense of what to expect.

Set a price.

Your price should be based on the amount of time and effort it will take somebody to answer your question, and the amount of detail you need. Google gives very good guidelines at http://answers.google.com/answers/pricing.html. You can—and should—surf around Google Answers to find out what people have paid for answers similar to the one you seek.

Choose a category.

If the appropriate category is not immediately clear, you can research existing questions to find the right one—or go for Miscellaneous. Most categories have subcategories, but you can leave that blank (choose No Subcategory).

Click “Continue to payment information.”

If you haven’t already created an account or logged in, Google asks you to do so now. Once you’re in, Google takes you to a page where you fill in your credit card and billing info.

The bottom of the screen shows you what your question will look like once it’s posted, so take a gander, and if you don’t like what you see, click “Go back and edit question.”

When you’re ready, click “Pay listing fee and post question.”

Note

At this point, Google charges you only the listing fee (50 cents). When and if somebody answers your question, Google charges the answer fee, too. (Google tallies your charges and sends them to your credit card every 30 days, or every time your total fees reach $25, whichever comes first.)

That’s it. You can lounge around and wait for somebody to answer your question, or you can post a new one. If nobody is trying to answer your question at the moment, you can tinker with it or cancel it, as discussed in the next section.

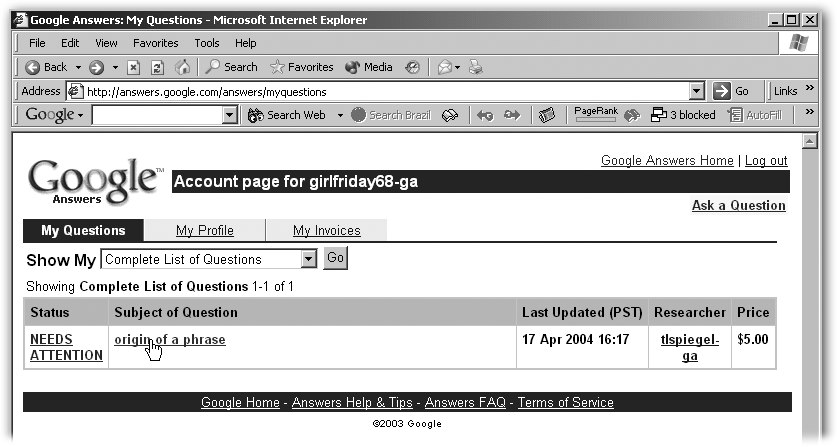

After you’ve posted your question, Google gives the chance to jump to your account page (Figure 4-19), which you can also reach by clicking the My Account link at the top of any Google Answers page. My Account has three tabs: My Questions, My Profile, and My Invoices.

Figure 4-19. The menu above the list of questions lets you filter for answered questions, unanswered questions, and cancelled or expired questions—a nice way to home in on a question if you have dozens listed.

My Questions is the important one right now, giving you a list of all the questions you’ve posted. There are three possible statuses for a question: open (not yet answered or expired), needs your attention (explained in Section 4.2.5.2), and closed (answered satisfactorily, canceled, or expired). From the list, click any subject to jump to the View Question page, which shows the details of that post.

Hopefully, the question you just posted is clear and your price is intriguing enough to provoke a researcher to lock it. If somebody has locked a question, she’s currently trying to answer it, and other researchers can’t touch it. You can tell when your question is locked because padlock icons appear all over the View Question page and Google posts a big note at the top: “You cannot modify or comment on this question right now. It is currently being answered.”

Note

Just because somebody has locked your question doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily get an answer; they may try and then give up. But researchers can’t lock a question for more than four hours, so your query won’t get sucked into a black hole.

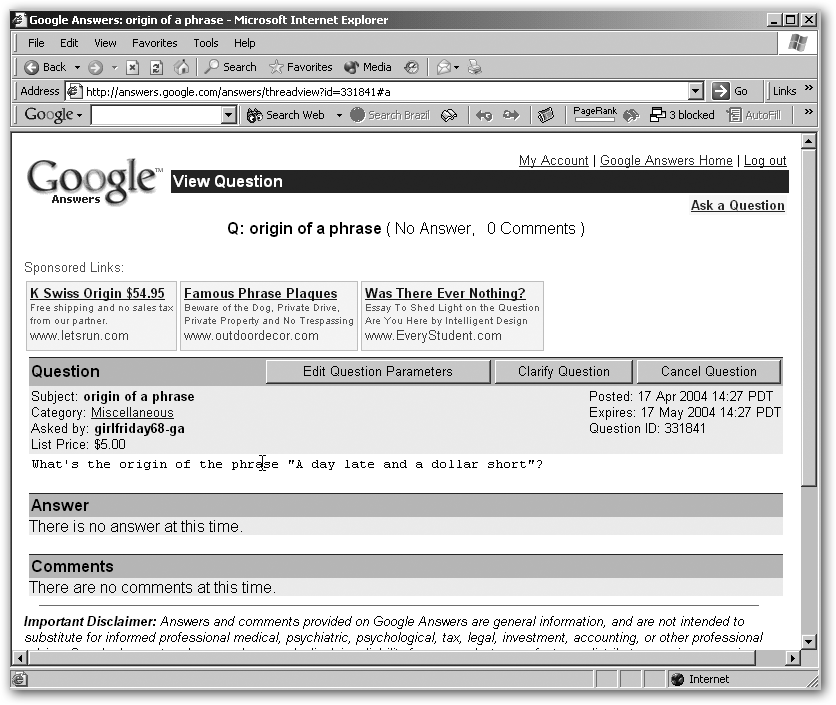

If somebody has locked your question, you can’t do much but wait to see whether they post an answer. But if a question is open and unlocked, you can make a few changes to it from the View Question page. Figure 4-20 explains.

Note

Quite possibly, a researcher will lock your question and try to answer it before you even have a chance to take any of these actions. That’s just one more reason to phrase your question carefully from the start.

Figure 4-20. Google doesn’t let you edit the text of your original message, but you can use the Clarify Question button to jump to a form where you can add specific details or follow-up questions to your post. Similarly, use the Edit Question Parameters button to change the category in which you’ve listed a question or the price you’re willing to pay. (Either of these factors can help you draw an answer if researchers seem to be ignoring you.) The Cancel Question button lets you close a question without paying the answer fee (Google still charges you the listing fee, however).

Your question can be resolved in any of a few ways.

In Googletopia, a researcher locks your question and answers it immediately and thoroughly. You’re happy with the answer, and all that’s left is to rate and perhaps tip the researcher—which Google prompts you to do.

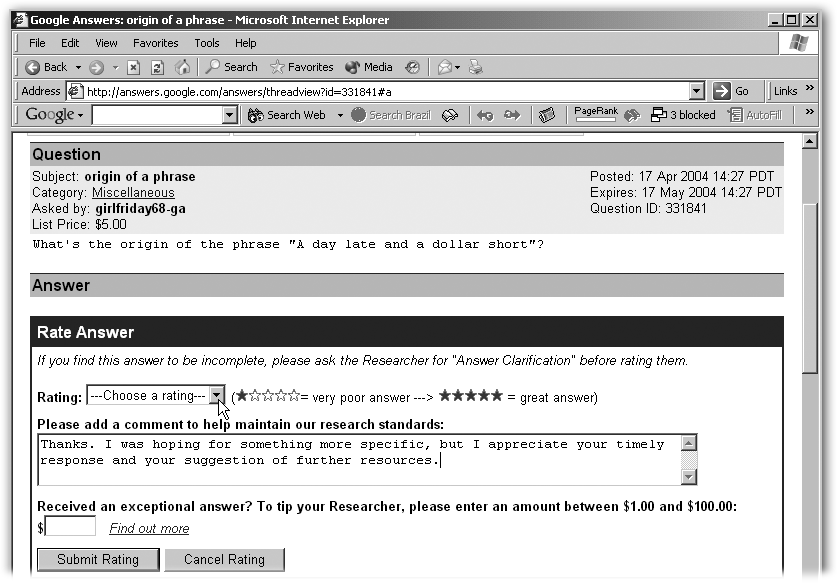

When a researcher posts an answer to your question, Google changes the status (on your My Questions page) from “open” to “needs attention.” Click the subject to reach the View Question page, where Google gives you two buttons: Request Answer Clarification, and Rate Answer. If you need no additional information from the researcher, click Rate Answer to jump to the form shown in Figure 4-21.

Figure 4-21. Use the menu on this page to choose a rating (up to five stars), and then type in a brief note about the quality of the answer. If you thought the answer was outstanding, you can tip the researcher, too. When you’re done, click Submit Rating.

After you’ve submitted the rating, Google changes the question’s status from “needs attention” to “closed.”

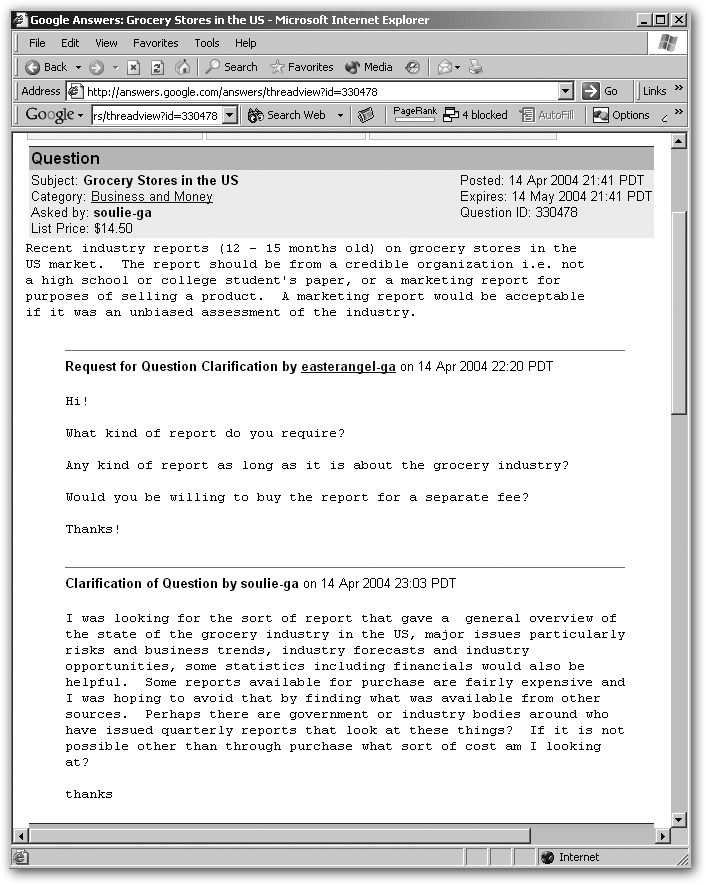

If a researcher doesn’t understand all or part of your question, he can post a Request for Question Clarification, which asks you to jump in with more info, or he can communicate with you by adding a comment (Section 4.2.5.6). Either way, it’s up to you to respond to keep things moving—although other people can post comments at any time.

If you’ve got a Request for Question Clarification, the status of your question (on your My Questions page) changes from “open” to “needs attention.” Click the subject to jump to the View Question page, where Google shows you the full request for more information. You also get a button that takes you to a page to type in and submit your clarification. Google adds both the request and your response to the public posting of your question (Figure 4-22).

Figure 4-22. You and the researcher may go back and forth a few times until you understand each other.

Once the researcher has posted an official answer, it’s time to rate and possibly tip him, as described in the box in Section 4.2.6.

Note

Because Google doesn’t charge your account until an official answer appears, a researcher who’s found something but isn’t sure whether it meets your needs may show what she’s got so far by posting it in a Request for Question Clarification or in a comment, asking if you approve. If you do, she can then post the information as an answer, which triggers the fee.

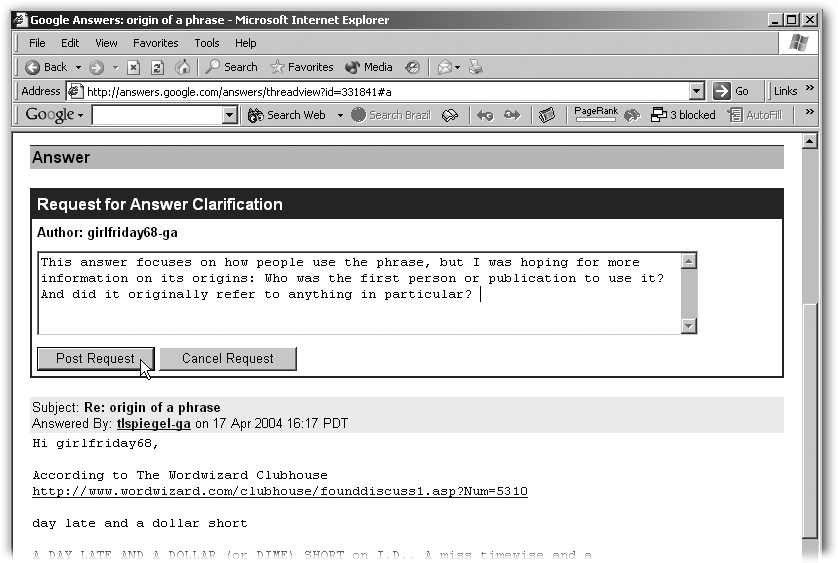

If a researcher posts an answer but it doesn’t satisfy you, you should ask for more information before you rate the answer. Chances are, by explaining where he went wrong, you’ll help the researcher figure out what you want.

To ask for further information, go to View Question page (choose My Account → My Questions, and then click the subject of the question). Then click Request Answer Clarification to jump to the form shown in Figure 4-23.

If you’ve had a few exchanges with the researcher, and you’re getting nowhere, you have a few choices. You can accept the answer and give the researcher a moderate or low rating. You can repost your question, which allows another researcher to try to answer it. When you repost (which you can only do once per question), Google credits you for the original answer fee, and it doesn’t charge a second listing fee. Finally, you can request a refund and cancel the question. If you choose this option—which you can do only within 30 days after the answer has been posted— Google requires you to give a reason, which it then posts publicly with your question.

Requests for reposts and refunds are serious business on Google Answers, and you should consider these options only after you’ve tried hard to resolve things with the researcher. The form for reposts and refunds is the same, and you can find it at http://answers.google.com/answers/refundrequest.

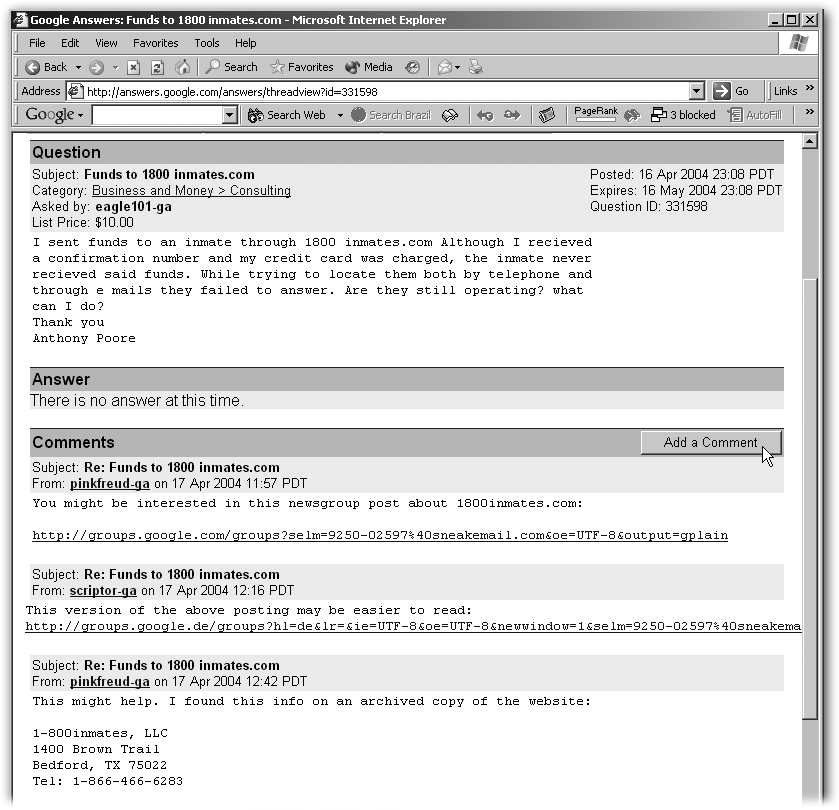

Surprisingly often on Google Answers, the researchers or other civilians post comments that can answer your question. (Anyone with a Google Answers account, including you, can post a comment to any question.) If your question can have many answers, or if the answer is likely to be an opinion, you might draw a handful—or an avalanche—of comments. Researchers can also use comments to partially answer a question (Figure 4-24) or to point you to previous posts that answer your question.

Figure 4-24. If the comments answer your question before a researcher has posted an official answer, you can cancel your question from the View Question page. (Google still charges you the 50-cent listing fee, but it doesn’t charge you for the comments.) Once you close a question, it remains in the listings, but nobody can answer it. (If you want your question removed for some reason, send a request, along with the Question ID, to answers-editors@google.com.)

If everybody seems to be ignoring your question, or you’ve noticed that a few researchers have locked it but nobody’s answering it, you might consider raising the fee, changing the category in which you’ve listed it so that different people might see it, or starting over with a simpler question.

Google lets you tweak your Answers account settings. To do so, click My Account from any Google Answers page, and then choose one of these tabs:

My Profile lets you change your email, password, nickname, and billing info.

My Invoices shows you what Google will charge your credit card, based on the status of your current questions. For example, if you have two open questions and one recently answered $15 question, Google shows the three listing fees at $.50 each, the answer at $15, and your total debits as $16.50.

Get Google: The Missing Manual, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.