Suppose you’ve opened iMovie and clicked the Create a New Project button. At this moment, then, you’re looking at an empty version of the screen shown in Figure 4-5. Connect your camcorder to the FireWire cable and turn it on. This is where the fun begins.

Click the little movie-camera symbol on the iMovie screen, if necessary, to switch into Camera Mode, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Tip

If you turn on your camcorder after iMovie is already running, the program conveniently switches into Camera Mode. (iMovie only does so the first time you power up the camcorder during a work session, however, to avoid annoying people who turn the camcorder on and off repeatedly during the editing process to save battery power.)

The Monitor window becomes big and blue, filled with the words “Camera Connected.” (If you don’t see those words, check the troubleshooting steps in Appendix B.) This is the first of many messages the Monitor window will be showing you. At other times, it may say, “Camera No Tape,""Camera Fast Forward,""Camera Rewinding,” and so on.

Tip

If no camcorder is connected and turned on, iMovie automatically shows you what the Mac is “seeing” through its iSight camera, if any (the iMac and MacBook Pro have one built in, for example). This effect may freak you out if the camcorder isn’t correctly hooked up—suddenly you’re seeing your own face on the screen, even though the camcorder is pointing away from you!

(Once the camcorder is correctly set up, you can switch between it and the built-in camera using the little camcorder icon pop-up menu.)

Figure 4-6. While you’re importing footage, the time code in the upper-left corner of the clip on the Clips pane steadily ticks away to show you that the clip is getting longer. Meanwhile, the Free Space indicator updates itself, second by second, as your hard drive space is eaten up by the incoming footage. The square Stop button does exactly the same thing as clicking the Play button a second time. The Pause button also halts playback, but it freezes the frame instead of going to a blank screen.

Now you can click the Play, Rewind, Fast Forward, and other buttons on the screen to control the camcorder (see Figure 4-6).

You’ll probably find that you have even more precise control by using the mouse to control the camcorder than you would by pressing the actual camcorder buttons. (The Space bar turns the Import button on and off, as described below. Otherwise, though, no keyboard shortcuts control these buttons.)

Tip

If, while the tape is playing, you click and hold your mouse button down on a Rewind or Fast Forward button, playback continues at twice its usual speed.

What you’re doing now, of course, is scanning your tape to find the sections that you’ll want to include in your edited movie.

After reading all the gushing prose about the high quality of digital- video footage, when you first inspect your footage in the Monitor window, you might wonder if you got ripped off. The picture may not look anything like DVD quality.

This video quality is temporary and visible only on the Mac screen. The instant you send your finished movie back to the camcorder, or when you export it as a QuickTime movie or DVD, you get the stunning DV quality that was temporarily hidden on the Mac screen.

Still, you’ll spend much of your moviemaking time watching clips play back, so it’s well worth investigating the different ways iMovie can improve the picture.

Good. If you have a fast Mac, a great way is to choose iMovie → Preferences, click the Playback tab, and then choose " Highest (field blending).” The only reason you’d want to choose one of the lower-quality settings, in fact, is if you experience hiccups during playback, usually in complicated movies on slowish Macs.

Tip

iMovie’s Preferences dialog box contains a slew of useful options. They’re cited so frequently in this book that it’s probably worth memorizing its keyboard shortcut: ⌘-comma.

As a bonus, that keystroke works to open the Preferences dialog box in all of the other iLife programs, too, not to mention Microsoft Word, Keynote, Safari, and others.

Better. An even better solution is to choose iMovie → Preferences, click Playback, and turn on “Play DV project video through to DV camera."You’ve just told iMovie to play the video through your camcorder. In other words, if you’re willing to watch your camcorder’s LCD screen as you work instead of the onscreen Monitor window, what you see is what you shot—all gorgeous, all the time. (You hear the audio only through the camcorder, too.)

Best. The ultimate editing setup, though, is to hook up a TV to your camcorder’s analog outputs. That way, you get to edit your footage not just at full quality, but also at full size. The camcorder, still connected to the Mac via its FireWire cable, passes whatever you’d see in the Monitor window straight through to the TV set, at full digital-video quality. This is exactly the way professionals edit digital video— on TV monitors on their desks.

The only difference is that you paid about $99,000 less for your setup.

When you’re in Camera Mode, an Import button appears just below the Monitor window. When you click this button (or press the Space bar), iMovie imports the footage you’re watching, storing it as digital-video movie files on the Mac’s hard drive. You can ride the Space bar, tapping it to turn the Import button on and off, capturing only the good parts as the playback continues.

During this process, you’ll notice a number of changes to your iMovie environment (Figure 4-6):

The Import button lights up in blue.

As soon as you click Import, what looks like a slide appears in the first square of the Clips pane, as shown in Figure 4-5. That’s a clip—a single piece of footage, a building block of an iMovie movie. Its icon is a picture of the first frame.

Superimposed on the clip, in its upper-left corner, is the length of the clip expressed as " minutes:seconds:frames.” You can see this little timer ticking upward as the clip grows longer. For example, if it says 1:23:10, then the clip is 1 minute, 23 seconds, and 10 frames long.

Getting used to this kind of frame counter takes some practice for two reasons. First, computers start counting from 0, not from 1, so the very first frame of a clip is called 00:00. Second, remember that there are 30 frames per second (in NTSC digital video; 25 in PAL digital video). So the far-right number in the time code (the frame counter) counts up to 29 before flipping over to 00 again—not to 59 or 99, which might feel more familiar. In other words, iMovie counts like this: 00:28…00:29…1:00…1:01.

Tip

Standard DV camcorders record life by capturing 30 frames per second. (All right, 29.97 frames per second; see the box in Section 12.4.1.3.)

That, for your trivia pleasure, is the standard frame rate for North American television. Real movies, on the other hand—that is, footage shot on film—roll by at only 24 frames per second. The European PAL format runs at 25 frames per second.

iMovie is a Mac OS X–only program. As a result, you gain a huge perk: Your Mac doesn’t have to devote every atom of its energy to capturing video. While the importing is going on, you’re free to open other programs, surf the Web, crunch some numbers, organize your pictures in iPhoto, or whatever you like.

The Mac continues to give processor priority to capturing video, so your other programs may act a little drugged. But this impressive multitasking feat still means that you can get meaningful work or reading done while you’re dumping your footage into iMovie in the background.

If you click Import (or press the Space bar) a second time, the tape continues to roll, but iMovie stops gulping down footage to your hard drive. Your camcorder continues to play. You’ve just captured your first clip(s).

If you let the tape continue to roll, you’ll notice a handy iMovie feature at work. Each time a new scene begins, a new clip icon appears in the Clips pane. The Clips pane scrolls as much as necessary to hold the imported clips.

What iMovie is actually doing is studying the date and time stamp that DV camcorders record into every frame of video. When iMovie detects a break in time, it assumes that you stopped recording, if only for a moment, and therefore that the next piece of footage should be considered a new shot. It turns each new shot into a new clip.

This behavior lets you just roll the camera, unattended, as iMovie automatically downloads the footage, turning each scene into a clip while you sit there leafing through a magazine. Then later, at your leisure, you can survey the footage you’ve caught and set about the business of cutting out the deadwood.

In general, this feature doesn’t work if you haven’t set your camcorder’s clock. Automatic scene detection also doesn’t work if you’re playing from a non-DV tape using one of the techniques described in Section 4.14.

Tip

If you prefer, you can ask iMovie to dump incoming clips into the Clip Viewer at the bottom of the screen instead of the Clips pane. You might want to do that when, for example, you filmed your shots roughly in sequence. That way, you’ll have to do much less dragging to the Clip Viewer when it comes time to edit.

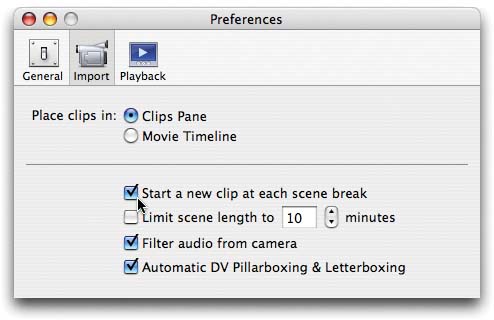

To bring this about, choose iMovie → Preferences and click Import. Where you see “Place clips in,” click Movie Timeline. Click OK. Now when you begin importing clips, iMovie stacks them end to end in the Timeline instead of on the Clips pane.

If you would prefer to have manual control over when each clip begins and ends, iMovie is happy to comply. Choose iMovie → Preferences, click Import, and proceed as shown in Figure 4-7.

Once you’ve turned off the automatic clip-creation feature, iMovie logs clips only when you click Import (or press Space) once at the beginning of the clip, and again at the end of the clip.

Once you start editing your videos, you’ll discover that iMovie is a very, very forgiving program. You can chop out part of a clip today—and then return next week or even next year and change your mind. iMovie will happily restore the missing footage.

That trick works because iMovie never really deletes any video when you shorten a clip. On your hard drive, the entire clip is still lying there, ready to be restored to your project.

As a result, iMovie projects can take up many times more disk space than you’d expect. For example, a one-minute video ought to take up about 200 megabytes of hard drive space. But if it’s composed of several different edited clips, that project could wind up occupying five times as much space on your hard drive, or even more.

You can read more about this habit in Section 5.3. But for now, note that iMovie 6 introduces a new feature that’s designed to counteract the program’s insatiable diskspace appetite—one you should know about before you start to import video.

Turns out that if you delete an entire clip (rather than just a piece of it), iMovie does indeed remove it completely from the project. That’s why there’s a new item in iMovie → Preferences, on the Import tab (Figure 4-7), called " Limit scene length to __ minutes.” If you set that number to, for example, 3, then iMovie will impose a clip break every three minutes. Having more subdivisions of your video means more opportunities to delete entire chunks.

For example, suppose you filmed the last 15 minutes of a soccer game, eating up 3.25 gigabytes of disk space. No matter how much you chop and edit that clip to create a 90-second “game highlights” video, the project will always occupy 3.25 gigabytes on your disk.

If you’d told iMovie to break up the clip every two minutes, though, you’ll wind up with eight different clips. (They still play seamlessly, with no visible hiccup between them.) You might find that there’s no usable footage at all in sections 2, 3, and 7—so you can delete those six minutes entirely, recovering that much disk space.

For best results, don’t attempt to use the footage- importing process as a crude means of micro-editing the footage on the fly. True, the ever-diminishing digits in the Free Space indicator may put you under pressure to limit the amount of footage you import. And it’s OK to ride the Import button so that you block out the obviously unusable sections. But resist the temptation to do finer editing this way. You’ll want to trim your clips with iMovie’s accurate snipping tools later.

This doesn’t mean that you must transfer everything from your camcorder (although many people do, just for the convenience). But when you come to a scene you want to bring into iMovie, capture 3 to 5 seconds of footage before and after the interesting part. Later, when you’re editing, that extra leading and trailing video (called trim handles by the pros) will give you the flexibility to choose exactly the right moment for the scene to begin and end. Furthermore, as you’ll find out in Chapter 6, you need extra footage at the beginnings and ends of your clips if you want to use crossfades or similar transitions between them.

iMovie veterans are used to a clip-length limit of 9 minutes, 28 seconds, and 17 frames (which is 2 gigabytes of hard drive space). But in iMovie HD, a clip can occupy up to 13 gigabytes of disk space. You can import an entire 60-minute DV tape’s worth of footage as a single icon on your Clips pane, if you like. (That would require, of course, that you’ve turned off automatic and timed scene breaks as described earlier, or that you ran your camcorder nonstop for a full hour.)

As noted earlier, the Free Space display (Figure 4-6) updates itself as you capture your clips. It keeps track of how much space your hard drive has left—the one onto which you saved your project.

This readout includes a color-keyed early warning system that lets you prepare for that awkward moment when your hard drive’s full. At that moment, you won’t be able to capture any more video. Look at the color of the text just beside the Trash (where it says, for example, “1.83 GB available”):

If the words are black, you’re in good shape. Your hard drive has over 400 MB of free space—room for at least 90 seconds of additional footage.

If the text becomes yellow, your hard drive has between 200 and 400 MB of free space left. In about 90 more seconds of capturing, you’ll be completely out of space.

When the words turn red, the situation is dire. Your hard drive has less than 200 MB of free space left. About one minute of capturing remains.

When the Free Space indicator shows that you’ve got less than 50 MB of free space left, iMovie stops importing and refuses to capture any more video. At this point, you must make more free space on your hard drive, either by emptying your Project Trash or by throwing away some non-iMovie files from your hard drive. (You don’t have to quit iMovie while you houseclean; just hide it by pressing ⌘-H.)

iMovie is also happy to capture video straight from a camcorder that doesn’t contain a tape. In other words, you can use your camcorder as though it were an iSight, sending whatever it “sees” directly into iMovie, live.

All you have to do is set its selector to Camera instead of VCR and take the tape out of the camcorder. Connect the camcorder to the Mac via FireWire, turn the camcorder on, and voilà: live, tapeless video capture.

Get iMovie 6 & iDVD: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.