The last chapters introduced you to Pages, the faithful transcriber of words, an able assistant for capturing your ideas and juggling them into presentable shape. Like any good assistant, though, Pages does more than just take down your words—it catalogs them, quietly fixes errors, and serves as a dictionary and a thesaurus, all rolled into one.

Pages juggles all of these roles by giving you a set of power tools to buzz through the jobs that support your writing: editing, sharing, and gathering feedback. The program’s Find & Replace feature makes short work of sifting through long documents; the built-in dictionary, thesaurus, and encyclopedia help you catch errors or find the perfect word; Pages’ in-house grammarian offers advice for sharpening your writing; and change tracking eases collaboration by keeping up with the edits and comments of multiple authors.

Together, this pit crew of support services adds up to a mean collection of typo busters, protecting you from careless mistakes while helping you find or solicit the right words to get your ideas across. This chapter explores them all.

Whether you’re completing your 400-page novel or just polishing a three-page letter, you often have to change a word, a phrase, or even a single character that appears repeatedly throughout the text. For example, as newsletter editor for Crazyland Wonderpark, you’ve been asked to write a book: Marketing Your Theme Park: The Missing Manual (congratulations!). As you zoom into your final chapters, your editor asks you to make a few changes:

You use the word “squirrel” far too often throughout the book (seriously—is there really nothing else in that petting zoo?) and it’s insensitive to the sciurophobics of the world. Now you have to change all 273 mentions of the word “squirrel” to something less likely to give sciurophobics palpitations. You opt for “rodent,” a much cuddlier word.

It’s great that the Teeny Tiny Dinosaur Safari features a model of the “Irritator” species of dinosaur, but please make sure Irritator is capitalized whenever it’s mentioned. (This isn’t a widely known species of dinosaur, and without the capitalization it sounds as though you’re saying derogatory things about your own attraction).

Your café menu has some unfortunate auto-corrections. For example, your burgers, soups, and salads are made with fresh cilantro and not fresh cement, right?

Half of your mentions of The World’s Most Haunted Public Toilet are in quotation marks, but you should instead italicize them with the Emphasis style and delete the quotes.

It’s Find & Replace to the rescue! Hunting through hundreds of manuscript pages for these changes would require some serious patience, but Find & Replace saves you the trouble, sifting through your document and making changes in the blink of an eye.

Pages’ Find & Replace feature is really two commands rolled into one: Find and Find & Replace. Sometimes you just need to find a word or phrase in your document. For example, you might want to find the pages where you use the phrase “everyone loves an irritator.” Here’s how to do that:

To open the Find & Replace window, choose Edit→Find→Find, press ⌘-F, or click the View button in the toolbar and then select Show Find & Replace.

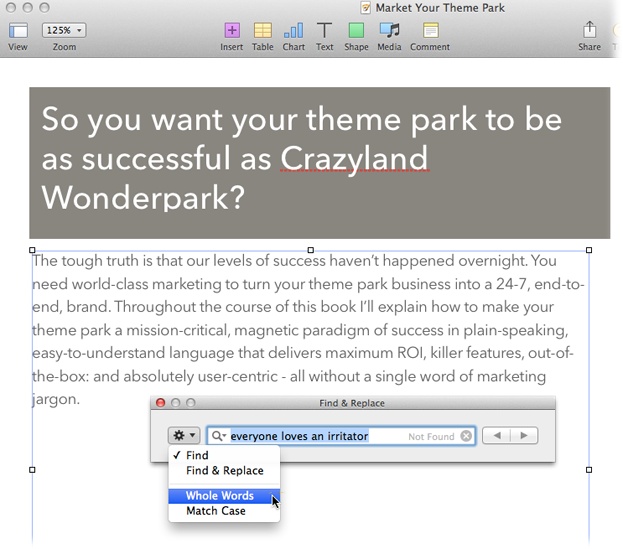

The Find & Replace window appears, as shown in Figure 4-1.

Enter the word or phrase you’re looking for in the Find field: everyone loves an irritator.

As you type, Pages highlights the first instance of the word or phrase that it finds and, at the right end of the Find field, displays a message that indicates how many instances it found (“8 found,” for example). Click the window’s gear icon and make sure Match Case is turned off (in other words, make sure it doesn’t have a checkmark next to it), because you want to find both capitalized and lowercase occurrences of this unfortunate phrase. In some cases, you’ll also want to turn on the Whole Words setting to prevent the search from turning up words that include merely part of your search term.

Click the window’s right-arrow button (or press Return), and Pages jumps to the next instance of your search term(s).

The right-arrow button tells Pages to search forward from your current selection. You can search backward from your present location by clicking the left-arrow button or by pressing Shift-Return.

Figure 4-1. To toggle the Match Case and Whole Words settings on and off, click the gear icon to display the menu shown here. When either of these options is turned on, it has a checkmark next to it, like the Find command here. If you can’t see the found word highlighted in your document, it could be hidden behind the Find & Replace window. To prevent this inconvenience, drag the Find & Replace window to one side before starting your search.

Work your way through your whole document by clicking the right-arrow button repeatedly (or pressing Return) to leap from result to result. If you want to make things more difficult for yourself, you can move backward and forward through your matches by clicking Edit→Find→Find Next/Find Previous.

On its own, the Find tool is a nifty way to zip straight to specific portions of your document. But things really get interesting when you mix in Replace. The Find & Replace feature can save you so much time and hassle that a better name might be Search & Rescue—it lets you motor through edits, telling Pages to automatically change matching words to something else. You can review each of these changes before applying them, or you can just take the leap and tell Pages to go ahead and change all matches across the board.

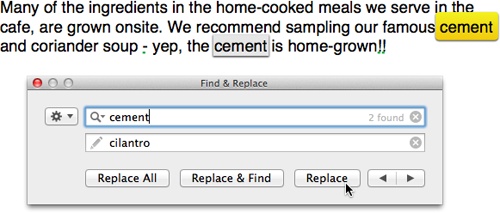

Some changes require a yes-or-no decision from you. For example, you might want to review every occurrence of the words “cement” and “cilantro” to make sure you’re using the right word in the right context. When you do find a mistake, you can either tell Pages to correct it or leave it untouched. Here’s how:

Call up the Find & Replace window by choosing Edit→Find→Find, pressing ⌘-F, or clicking the View button in the toolbar and selecting Show Find & Replace.

If the window contains only one text field (the Find field), you need to add a second text field (the Replace field) by clicking the gear icon and then selecting Find & Replace. Figure 4-2 shows this two-text-field setup in action.

Enter the word you’re looking for in the Find field: for example, cement.

In the Replace field, enter the word that you may want to use instead: cilantro.

Click the right-arrow button (or press Return), and Pages jumps to the next occurrence of “cement” in your document.

Tasty herb or unlikely-to-be-tasty building material? After examining the word in context, click the right-arrow button to leave it as is and jump to the next occurrence, or click Replace & Find to replace “cement” with “cilantro” and then move to the next occurrence. (This has the same effect as clicking the Replace button and then the right-arrow button.)

Figure 4-2. If you’re certain about the terms you’ve set up for your Find & Replace, click Replace All and Pages makes the change everywhere in your document and tells you how many occurrences it found. Click Replace to replace only the currently highlighted word, or click Replace & Find to replace the current word and move on to the next occurrence so you can evaluate it.

Some circumstances don’t require you to review every change. When you know that you definitely want to replace all instances of a word or phrase, the Replace All button is the answer. To capitalize every lowercase instance of “irritator” in your document, for example, type irritator in the Find field and Irritator in the Replace field, and then click Replace All. Pages instantly fixes all the irritators within your document, without asking for your opinion on each occurrence.

When working with Replace All, it’s particularly important to be clear about what you’re replacing. When you want to change only a specific word, click the Find & Replace window’s gear icon and click Whole Words. This tells Pages not to confuse the word you’re searching for with parts of other words. That way, when you want to change Sue to Betty, the words issue and Suez don’t turn into isBetty and Bettyz.

Pages’ Find & Replace feature doesn’t limit you to “normal” words and characters—you can just as easily search for spaces, tabs, line breaks, and a range of other invisible characters (for more on “invisibles,” see Keeping Lines and Paragraphs Together). Say that you want to sweep out extra spaces from your document, replacing two or more spaces with a single space. No problem: Type two spaces in the Find field, type one space in the Replace field, and then click Replace All. Pages replaces all your double spaces with single spaces. But what if, in a space bar-addled frenzy, you typed three or more spaces? Just click Replace All again to replace those extra spaces. Continue clicking Replace All until the indicator at the right end of the Find field reads “0 found.”

One of the most appreciated features of the modern word processor is its ability to corect embarassing misspellings. Pages can’t save you from choosing the wrong word—it still can’t tell a “heroine” from “heroin,” or “there” from “their” from “they’re”—but it can at least let you know when you’ve misspelled “correct” or “embarrassing.”

Make a spell check the last stop before you consider any document finished. Even if you’re a spelling bee champ, typos eventually befall anyone who puts fingers to keyboard. To catch these gaffes, Pages makes use of OS X’s systemwide spell checker—tapping into the same dictionary used by other Apple programs like Mail, Keynote, Numbers, TextEdit, and iPhoto.

Unless you tell it otherwise, Pages quietly watches as you type. If you misspell a word, Pages tries to help you out in a couple of different ways.

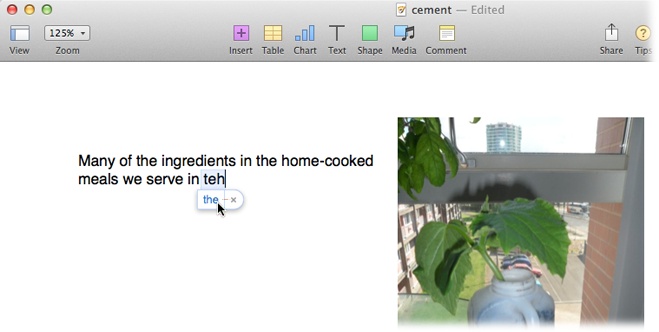

When you first install Pages, the program’s Correct Spelling Automatically feature is turned on. So if you type a word that Pages doesn’t recognize, the program displays the word it thinks you were trying to spell in a little pop-up like the one in Figure 4-3 (unless Pages has absolutely no idea what word you’re trying to spell!) For example, if you type “erally,” Pages might suggest “really.” If you press the space bar on your keyboard, Pages assumes you’re OK with its correction and updates your misspelling to what it suggested. If you disagree with the replacement, click the x in the pop-up window to keep your entry as it is, and then you can hit the space bar and continue on your way. (If Pages changes the spelling of a word, it indicates this by underlining the corrected word in blue—but only until you type the next word. So if you aren’t careful, Pages may make changes that you don’t notice.)

Fortunately, you’re not stuck with this feature if you think it’s more trouble than it’s worth (and you may very well think that—there are whole websites dedicated to embarrassing typos caused by auto-correct features like this). To turn it off, click Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Correct Spelling Automatically, which removes the checkmark next to this option.

Figure 4-3. This screenshot shows everyone’s favorite typo: “teh” instead of “the.” To ignore Pages’ suggested correction, click the x in the pop-up window. To admit that Pages is right and you’re in the wrong, either click the correctly spelled word in the pop-up window or press the space bar on your keyboard—both methods give you “the.”

If you turn off Correct Spelling Automatically (or if you leave it on but you type a word that Pages doesn’t know and doesn’t have a suggestion for), the program flags words it doesn’t recognize with a red dashed underline and provides fast access to spelling suggestions—if you want them. This Check Spelling While Typing feature is turned on by default, but you can toggle it on and off by choosing Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Check Spelling While Typing.

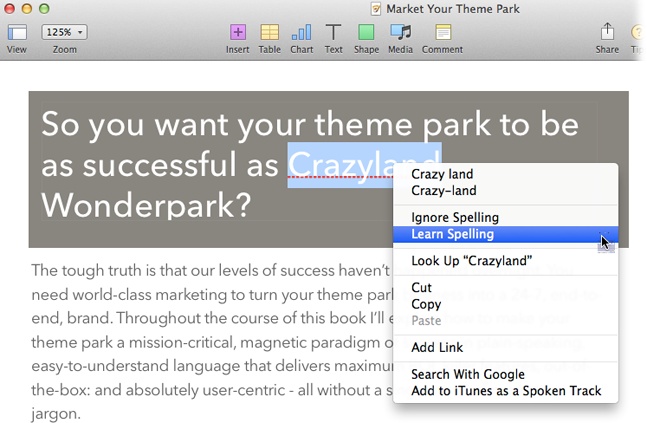

When Pages adds a red underline to a suspicious spelling, Control-click the word. A shortcut menu appears, topped with the spell checker’s guesses at correct spellings (Figure 4-4). Click the word you’re after, and Pages makes the correction.

Note

If you want Pages to check your grammar, too, head to Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Check Grammar with Spelling. From then on, when you see a word marked with a green underline, it means Pages is questioning your grammar.

Figure 4-4. The easiest way to correct misspellings is to Control-click the underlined words to see this shortcut menu. Pages’ best guesses at the correct spelling are at the top of the menu. Click the spelling you want in the list, and Pages makes the substitution in your document. If the flagged word is actually correctly spelled—a name, for example—choose Learn Spelling to add that word to the dictionary.

Just because Pages flags a word doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s misspelled—only that the spell checker doesn’t recognize it. This is common, for example, with names, addresses, or specialized technical lingo not included in your Mac’s dictionary. (This also happens with foreign words, but that’s a special case—more on that in a moment.) You can teach the spell checker a new word by Control-clicking a red-underlined word and choosing Learn Spelling from the shortcut menu. Pages adds the word to your Mac’s dictionary so that it stops getting flagged—not only by Pages but also by every other program that uses the Mac operating system’s spell checker.

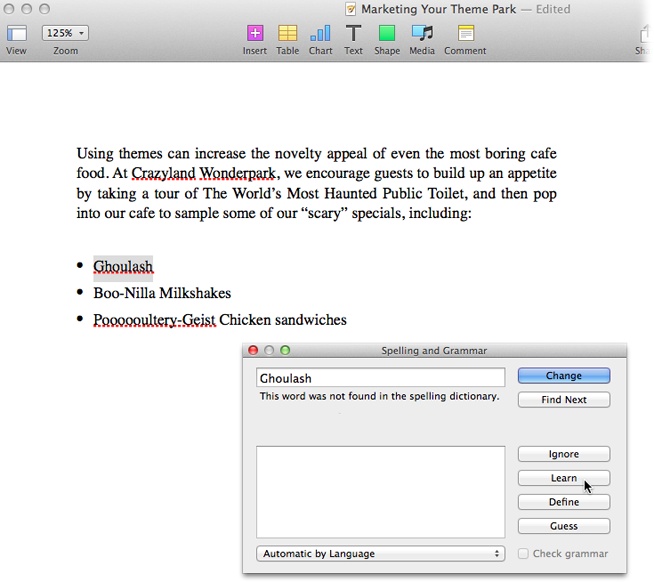

Another choice in the shortcut menu is Ignore Spelling. Choose this setting when you don’t want the highlighted word flagged in the current document, but you don’t want to add it to the dictionary either. For example, say your chapter titled “Marketing Your Theme Park Cafe” makes several mentions of Ghoulash, Boo-Nilla milkshakes, and Poooooultery-Geist Chicken sandwiches, in honor of the World’s Most Haunted Public Toilet attraction. If you choose Ignore Spelling when Pages first stumbles across one of these frightening foodstuffs, Pages will stay quiet about these words—as well as their lowercase variations—for the remainder of the document. In new documents, however, it will continue to catch these words as misspellings.

Note

Your Ignore Spelling commands last until you close the document. When you reopen the file later, Pages once again flags your previously ignored words as unrecognized.

Once you’ve chosen the correct spelling, Learn Spelling, or Ignore Spelling from the shortcut menu, Pages removes the red underline.

Whoops! You accidentally told the spell checker to learn the word “Boo-Nilla,” and now none of your programs spot this as a misspelling. No problem: Control-click the word and choose Unlearn Spelling from the shortcut menu. Ah, the red underline is back. Pages and all the other programs that use the OS X spell checker immediately start flagging the word as a misspelling again. (This maneuver works only for words that you’ve added yourself—OS X doesn’t let you remove words from its standard dictionary.)

If red underlines are derailing your creative train of thought, you can turn them off. Choose Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Check Spelling While Typing to remove the checkmark in front of that menu item. The red lines vanish and you can turn your attention back to your masterpiece. When you’re ready to accept the spell checker’s help again, you can ask it to take you through all the unknown words in your document one by one.

To get started, place your insertion point where you’d like to begin spell checking—at the beginning of the document, for example—and then press ⌘-; (semicolon) or choose Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Check Document Now to tell Pages to point out the first word it doesn’t recognize. Control-click the word to choose an alternative or to tell Pages to learn or ignore the word. Press ⌘-; again to move onto the next misspelled word.

If all this Control-clicking is wearing you down, you can call on the Spelling and Grammar window to guide you through your document, showing you each unrecognized word and its suggested replacements simultaneously. Open this window by putting your insertion point where you’d like to start spell checking, and then choosing Edit→Spelling and Grammar→Show Spelling and Grammar. The Spelling and Grammar window shows you the first misspelled word and suggests fixes, as shown in Figure 4-5.

Pages offers its recommendations with a list of suggested spellings. If you see the correct word, double-click it (or click once to select it and then click Change)—Pages replaces it in the document and moves on to the next misspelling. The Ignore button skips this word for the rest of the document; the Learn button adds it to the dictionary. If you just want to skip over the word and move on to the next misspelling, click Find Next (or press ⌘-;).

Figure 4-5. The Spelling and Grammar window lets you click your way through the misspelled words Pages has flagged, see its guesses, correct misspellings, teach the dictionary new words, and ignore certain words. Click Define to launch the dictionary and learn more about the currently selected word. Pages highlights each unrecognized word in the document as you do this, so you can see the word’s context.

If none of the alternative spellings that Pages displays is correct, or if the program doesn’t provide any suggestions, you can type the correct spelling yourself in the field at the top of the Spelling and Grammar window, and then click Change. You can also tell Pages to check your document for questionable grammar by turning on the Check Grammar checkbox at the bottom of the window.

Your Mac knows lots of languages and has a dictionary for each of them. Normally, the spell checker uses the dictionary that matches your system-wide language setting. (If you change that setting in ![]() →System Preferences→“Language and Region,” you also change the language for your menus and dialog boxes.)

→System Preferences→“Language and Region,” you also change the language for your menus and dialog boxes.)

But say that you write multilingual documents, or perhaps you’re known to sprinkle your prose with languages of the world to demonstrate your cosmopolitan credentials. When Pages spell checks your document, it doesn’t find those foreign-language words in your standard dictionary and incorrectly marks them as misspelled.

You can sidestep this international crisis by temporarily switching the spell checker to a new language. You can do this by clicking the “Automatic by Language” drop-down menu in the Spelling and Grammar window and choosing from the long list of languages. Once you’ve safely navigated the foreign waters of your document, you can switch the spell checker back to your native tongue.

As helpful as the spell checker might be, you can’t rely exclusively on it to catch every mistake. For example, if you type “lightening” when you mean “lightning,” or “metal” when you mean “mettle,” Pages won’t spot the error, since these words are all in the dictionary and spelled correctly. Only you (or another reader) can spot correctly spelled but misused words. But we all might be forgiven the occasional lapse when we forget which version of a word is correct for the context: Do I use “affect” or “effect” here? “Your” or “you’re”? “Compliment” or “complement”? Fortunately, Pages offers a set of tools to help you answer those questions and also find lots more info about a word or phrase.

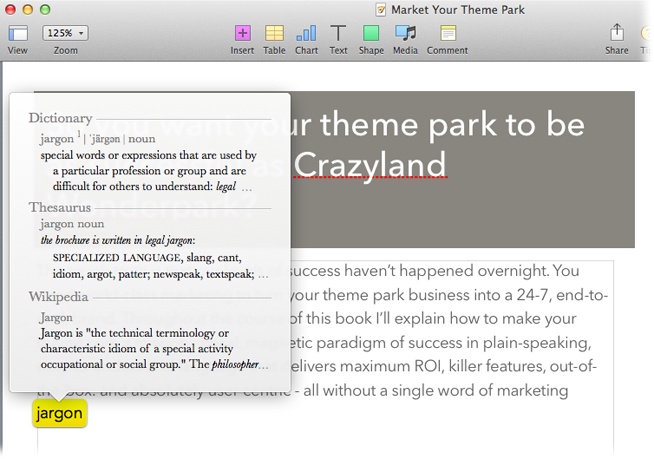

Your Mac comes with a full dictionary, complete with definitions, pronunciation, and usage notes—the whole shebang. You can look up a word directly from your Pages document by Control-clicking it and choosing “Look Up [word]” from the shortcut menu. Doing so opens a window showing you the dictionary definition, the related thesaurus entry, and the Wikipedia definition (discussed in more detail in the next section), as shown in Figure 4-6. Click any of these entries to expand it; for example, click the word “Dictionary” to see the full dictionary entry.

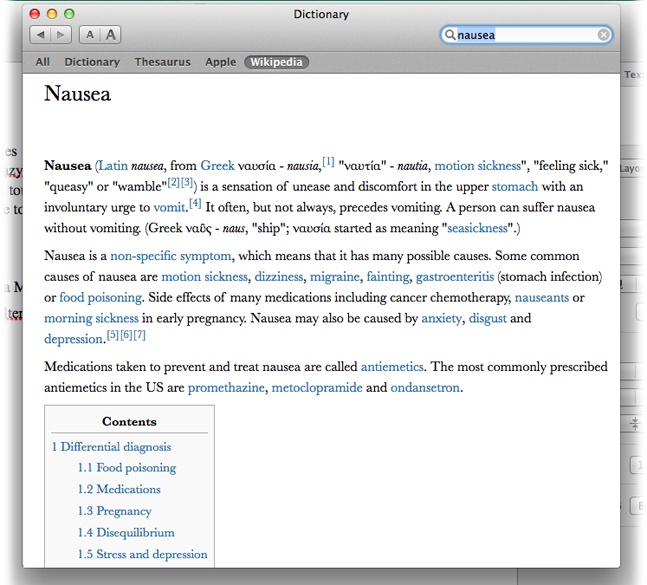

Say that the simple definition of “nausea” just doesn’t cut it, and imagine that you need all the facts, figures, and finer details to prove that Crazyland Wonderpark isn’t responsible for a recent visitor’s sudden bout of sickness. In such situations, Pages gives you a few easy ways to find detailed information from the Web about any topic.

When it comes to the dictionary/thesaurus/Wikipedia window, the Wikipedia section is particularly interesting. When you’re connected to the Internet, click this section’s heading to expand it and call up the encyclopedia entry for your word or phrase from Wikipedia, the Web’s free encyclopedia (as shown in Figure 4-7).

Figure 4-6. Control-click any word to read up on its meaning in the dictionary, look up synonyms and antonyms in the thesaurus, or read more background information on it by clicking the word “Wikipedia.”

Figure 4-7. The Dictionary window features a Wikipedia tab, which lets you read the Wikipedia encyclopedia entry for any word or phrase. Just keep in mind that Wikipedia is written by volunteers, so it’s always wise to check at least one other source to make sure Wikipedia’s info is correct.

Pages offers a similar shortcut for performing a Google search: Control-click the word in question, and then select Search With Google. Pages opens Safari and takes you straight to the Google search results for the word you Control-clicked.

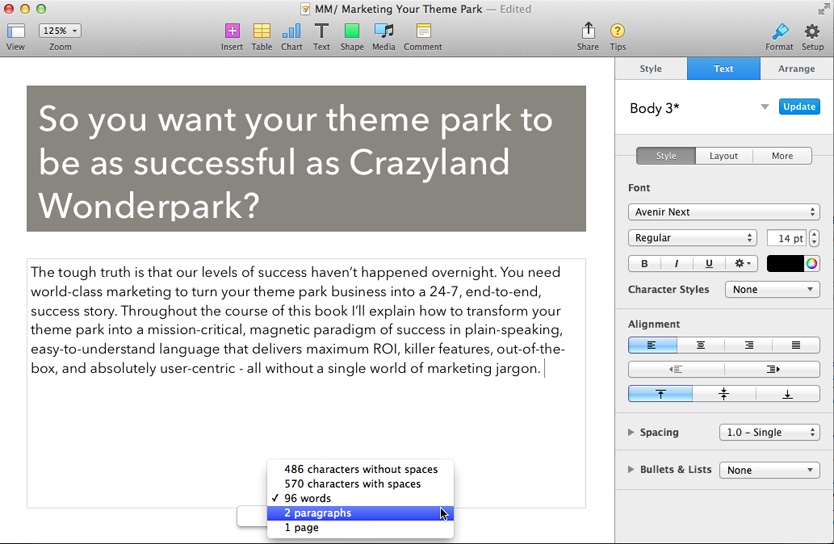

Whether you have a word-count goal (you’re writing a 5,000-word essay for a class, say) or simply a Rain Man–like fascination with numbers, Pages lets you keep track of the number of characters (with and without spaces), words, pages, and paragraphs in your documents. To see these statistics, click the View button in the toolbar and select Show Word Count. This adds a little Word Count box near the bottom of your document that updates as you add and remove words.

The Word Count box is also your ticket to checking the paragraph, page, and character count. Put your cursor over the Word Count box, and then click the little arrows that appear. Pages opens a drop-down list that contains these stats (see Figure 4-8).

Figure 4-8. When you first click the toolbar’s View button and choose Show Word Count, Pages displays your document’s word count in this box. If you’d rather see paragraph, page, or character count with spaces, or character count without spaces, instead, simply click the appropriate items in this list. (If you change your mind, you can always reopen this list and choose another item.) To close the Word Count box, click the View button again and select Hide Word Count.

If you want to see the statistics for a specific passage of your document, select the text you want to tally. The Word Count box updates to show you how many words, characters, pages, and paragraphs you’ve selected. To return to the figures for the entire document, just click anywhere outside the highlighted text to deselect it.

Pages offers one final automatic safety net to save you from fat-finger foibles on the keyboard. Most of the time, auto-correct chugs along quite happily on its own, but there are a couple of tweaks you can make to get even more out of it. To tweak the auto-correct’s settings, go to Edit→Substitutions→Show Substitutions. This opens the Substitutions window, where you can turn on, turn off, or update the following options:

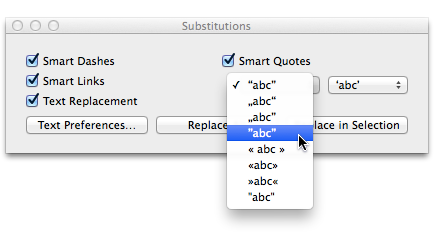

Smart Quotes. Smart quotes (also known as curly quotes) are usually “” and ‘’, but did you know there’s a whole world of exotic quotation marks out there? When this checkbox is turned on, you can use the two drop-down menus shown in Figure 4-9 to specify exactly what Pages should make double and single quotation marks look like.

Figure 4-9. Tell Pages to automatically convert double and single quotation marks (“ and ‘, respectively) to smart quotes by turning on the Smart Quotes checkbox. Set a style for the double quotation marks using the Substitution window’s first drop-down menu (the one that’s open in this screenshot), and set a style for single quotation marks using the second drop-down menu.

Smart Dashes. When this checkbox is turned on, Pages converts double dashes (--) to em dashes (—).

Smart Links. With this setting turned on, Pages turns all email and web addresses into hyperlinks (see Hyperlinks).

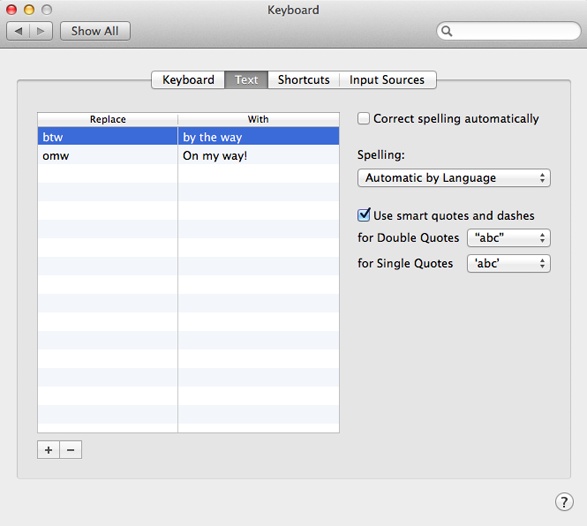

Text Replacement. This option lets you create your own rules for substituting one set of text for another. It’s particularly handy for inserting frequently used symbols such as © or ™ without having to memorize their keyboard shortcuts or resorting to the Characters window. Once you’ve turned on this checkbox, click the Text Preferences button to display a table of replacements (Figure 4-10). In this window, the Replace column lists text that Pages will automatically substitute for the corresponding text in the With column. Create your own replacement rules by clicking the + button in the lower-left corner of the window. To remove a rule, select it in the table and then click the – button. To disable all rules, close this window and return to the main Substitutes window, and then turn off the Text Replacements checkbox.

Figure 4-10. To create a new rule, click the + button in this window’s bottom left. Then, in the Replace column, type the text that you want Pages to replace, and in the With column type the replacement text. In this example, whenever you type “omw”, Pages will step in and replace it with “On my way!”

As you’ve seen, Pages provides a whole arsenal of tools to help you spot, prevent, and correct errors in your documents. In the end, though, these automated services can go only so far. No matter how cleverly programmed, a bucket-of-bolts wordbot is no substitute for the critical eye and creative mind of a living, breathing human editor. That’s especially true when you move beyond mechanical considerations of spelling or typos and into more writerly concerns of style and substance. Even there, though, Pages can be helpful: When you’re ready to solicit feedback from others, Pages plays traffic cop to keep the editing process flowing smoothly, monitoring every change made to your document.

Note

You may be able to use iCloud to share a Pages document that has change tracking turned on (see Modifying a Chart’s Data for more on iCloud) but change tracking stops working as soon as you share your document via iCloud. However, you can share a copy of a document that has change tracking turned on; see Emailing Your Document for details.

With change tracking, Pages quietly catalogs every edit made to your document, letting you review all additions, deletions, and replacements before accepting revisions into the final draft. While this can be handy even when you’re working on text all by your lonesome, it becomes invaluable when you’re collaborating with an editor, co-writing a document with others, or being critiqued by your boss. Change tracking builds a paper trail of a document’s edit history so that you and others can see exactly who changed what and when.

Note

Pages’ change tracking works seamlessly with Microsoft Word. So when you export a Pages document to Word format (Exporting to Microsoft Word)—or use Pages to open a Word document (Importing Files from Another Program)—Pages preserves the edit history. Word users can review your changes and vice versa.

To turn on change tracking, choose Edit→Track Changes. Pages reveals the review toolbar (shown in Figure 4-11) just below the regular toolbar, where you can scroll through comments and changes, and accept and reject changes. Pages calls attention to each change by adding a change bar, a vertical bar in the left margin next to each edit. (The line is color-coded to match the author who made that change.)

Figure 4-11. When you turn on change tracking, Pages displays the review toolbar and starts taking note of every edit. To add a comment, click the “+ Comment” button (see page 103 for details); to highlight a section of text, select it and then click Highlight. You can also use the Accept and Reject buttons to accept or discard the change where your insertion point currently is.

The number of changes waiting to be accepted or rejected is shown on the left end of the review toolbar. To review these changes, click the arrow buttons to move from one change to the next. When you’re looking at a change, a pop-up appears with more information about that change, and Pages highlights the relevant area in your document.

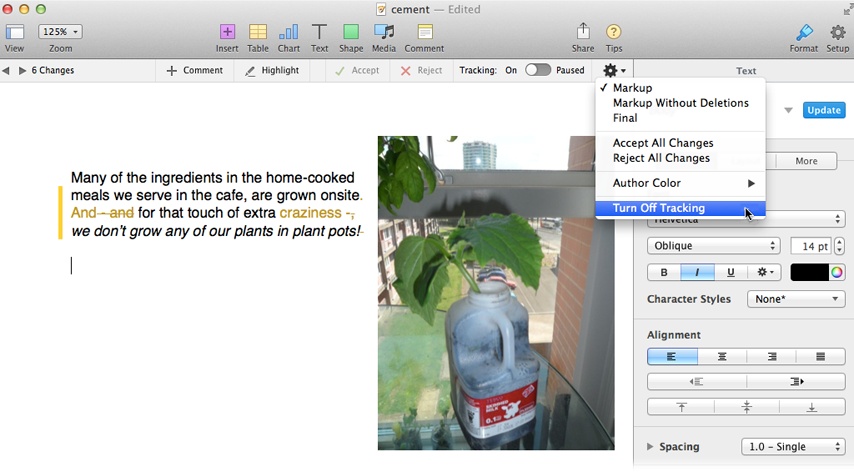

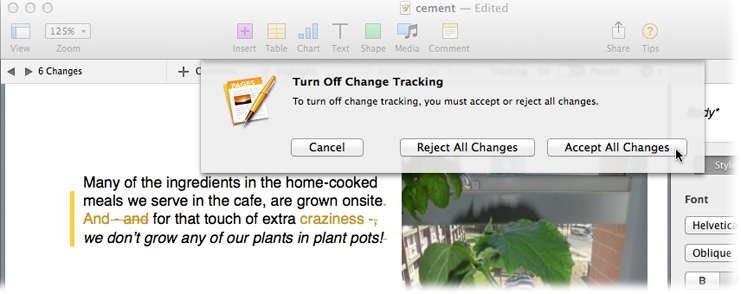

To turn off change tracking completely, click the gear icon, and then choose Turn Off Tracking. But be careful: When you turn off change tracking, you not only stop tracking future changes, you also lose the current change history. Pages pauses to ask if you really want to do this and, if so, lets you decide what to do with the current batch of changes, as shown in Figure 4-12.

Figure 4-12. When you turn off change tracking, Pages asks what it should do with the current set of changes. Clicking Accept All Changes keeps the current version as is. Clicking Reject All Changes throws out the edits and reverts to the original text. (Of course, if you click the wrong button, you can always choose Edit→Undo to turn change tracking back on and fix your mistake.)

A gentler way to shut down change tracking is to put it on pause. This temporarily puts the tracking on hold while maintaining the current edit history; Pages doesn’t track any changes that you make in paused mode. To pause change tracking, click the Tracking slider in the review toolbar to set it to Paused. To resume, click the slider to set it to the On position.

With change tracking on, you can step through every edit and decide whether you want to accept or reject each one. When you accept an edit, it becomes a permanent part of the text. When you reject an edit, Pages peels it back, reverting to the original, unedited text. In both cases, Pages removes the change from the edit history. Think of accepting or rejecting changes like checking off items on your editorial to-do list: Once you review a change and make your decision, Pages considers the edit closed and removes it from sight.

Use any of these methods to accept a change:

Cycle through the changes using the arrow buttons at the left end of the review toolbar. When you’re looking at a change’s pop-up, click the Accept icon.

Place the insertion point inside the edited text, and then click the Accept button in the review toolbar or the pop-up that appears.

Click the review toolbar’s gear icon, and then click Accept All Changes (this command does exactly what it says: accepts all changes).

Pages likewise gives you three ways to reject changes:

If you prefer to accept or reject changes from just a portion of the document, then select the text you’re interested in and then click the Accept or Reject in the review toolbar.

As handy as change tracking can be, all this markup sometimes makes your document too busy to let you focus on your work. When your text is thick with edits, it becomes heavy with dense patches of multicolored text, a forest of lines, a crowded review toolbar, and a confusing hash of strikethrough text. If you find yourself squinting just to follow the plot, you can tell Pages to make some cosmetic adjustments.

The review toolbar’s gear drop-down menu (shown in Figure 4-11) offers three options for dialing Pages’ markup detail up or down:

Markup. Pages displays deleted text with the strikethrough style, and new text is bolded. Both new text and deletions are color-coded by author. To change the color Pages uses, open the gear menu in the review toolbar and choose a new hue from the Author Color submenu.

Markup Without Deletions. Pages hides deletions and displays only new text. However, Pages still displays change bars to the left of lines where text was deleted.

Final. Pages displays text without markup. The result is that you see your document as it would look if you accepted all changes. You may be wondering how this is change tracking at all, but Pages actually continues to track the changes behind the scenes, so if you want to switch to Markup or Markup Without Deletions at a later date, you can.

If seeing your own text edits in a sickly yellow is getting you down, you can choose a new author color. In the review toolbar’s gear drop-down menu, choose Author Color and pick a new hue. Alas, you can’t choose colors for other authors, so you can’t impose your creative vision on others, but at least you have control over your own personal style.

While you’re busy overhauling your personal branding, you can also change your author handle. Unless you tell it otherwise, Pages labels your changes with your name from Address Book, but you can use any name you like. Go to Pages→Preferences, click the General button, and then enter your preferred moniker in the Author field.

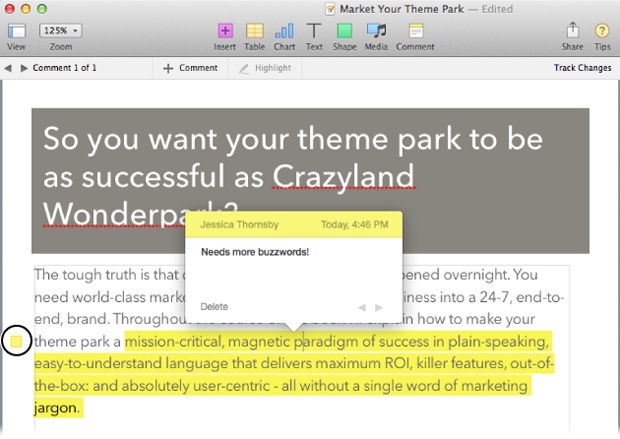

Besides keeping a record of changes, Pages’ change-tracking feature also lets you and other editors leave comments about the text. Comments are notes that don’t appear in the actual body of the text, but Pages lets you know these comments exist by highlighting the related text and adding a tally in the upper-left corner of the reviews toolbar (for example, “4 Changes & Comments”). To open a comment, put your cursor over the highlighted text. Like change pop-ups, comments are tethered to a particular text selection, making them a useful way to ask questions, offer suggestions, or leave yourself a reminder about a particular passage. They’re like Post-It notes that you slap on the document—temporary messages fixed to your text while also remaining separate from it. Comments have a colored band that matches your author color, so you can easily see who’s saying what.

To add a comment, select the text you want to annotate, and then click the “+ Comment” button in the review toolbar. Pages displays a comment pop-up and adds a colored square in the margin to the left of the original text (see Figure 4-13). Type your comment in the pop-up, which grows and shrinks to fit your text, and then click outside the pop-up when you’re done. To edit a comment, click its colored square (or click the text it’s attached to) to display it, and then click inside its pop-up and type away (you can edit other editors’ comments as well as your own). To delete a comment, click the Delete button in the comment’s pop-up, or delete the annotated text from your document.

Figure 4-13. Comments let you add notes and annotations to your text, a useful way to leave yourself research notes and reminders, or to gather suggestions as you pass a document around to a group for feedback. Every comment is anchored to a specific passage of text, which Pages highlights (as shown here). Pages also adds a colored square to the left of this text (circled).

You can hide all comments by choosing View→Comments and Changes→Hide Comments. To coax your document’s comments back into the open, go to View→Comments and Changes→Show Comments.

Although comments look similar to change pop-ups, they’re not technically part of change tracking. So you can leave comments when change tracking is turned off, and when you accept or reject all changes, your comments remain intact.

Before you email your business proposal to the client, it’s probably best to clear out the comments making fun of the ridiculous shirt he wore to the meeting last Thursday. Ditto for the change tracking that shows that you arbitrarily doubled your fee five minutes before sending the proposal. You get the idea: After you’ve gathered and reviewed all the edits and finally rounded the corner into final-draft territory, turn off change tracking by going to Edit→Turn Off Tracking, and then remove all those incriminating comments by going to Edit→“Remove Highlights and Comments.”

Now your scrubbed and typo-free document is ready to be shared with the world. But before you do that…wouldn’t your masterpiece look better with a table of contents, some numbered page footers, or perhaps a multicolumn layout? That’s the stuff of document formatting, which just happens to be the subject of the next chapter.

Get iWork: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.