Chapter 4. Advanced SAX

What you’ve seen regarding SAX so far is essentially the simplest way to process and parse XML. And while SAX is indeed named the Simple API for XML, it offers programmers much more than basic parsing and content handling. There is an array of settings that affect parser behavior, as well as several additional handlers for edge-case scenarios; if you need to specify exactly how strings should be interned, or what behavior should occur when a DTD declares a notation, or even differentiate between CDATA sections and regular text sections, SAX provides. In fact, you can even modify and write out XML using SAX (along with a few additional packages); SAX is a full-featured API, and this chapter will give you the lowdown on features that go beyond simple parsing.

Properties and Features

I glossed over validation in the last chapter, and probably left you with

a fair amount of questions. When I cover JAXP in Chapter 7, you’ll see

that you can use either a method (setValidating()) or a set of classes

(javax.xml.validation) to handle

validation; you might expect to call a similar method—setValidation() or something similar—to

initiate validation in SAX. But then, there’s also namespace awareness, dealt with quite a bit in Chapter 2 (and Chapter 3, with respect

to Q names and local names—maybe setNamespaceAwareness()? But what about

schema validation? And setting the location of a schema to validate on,

if the document doesn’t specify one? There’s also low-level behavior,

like telling the parser what to do with entities (parse them? don’t

parse them?), how to handle strings, and a lot more. As you can imagine,

dealing with each of these could cause real API bloat, adding 20 or 30

methods to SAX’s XMLReader class.

And, even worse, each time a new setting was needed (perhaps for the

next type of constraint model supported? How about setRelaxNGSchema()?), the SAX API would have

to add a method or two, and re-release a new version. Clearly, this

isn’t a very effective approach to API design.

Tip

If this isn’t clear to you, check out Head First Design Patterns, by Elisabeth and Eric Freeman (O’Reilly). In particular, read up on Chapter 1 (pages 8 and 9), which details why it’s critical to encapsulate what varies.

To address the ever-changing need to affect parser behavior, without causing constant API change, SAX 2 defines a standard mechanism for setting parser behavior: through the use of properties and features.

Setting Properties and Features

In SAX, a property is a setting that requires passing

in some Object argument for the

parser to use; for instance, certain types of handlers are set by

specifying a URI and supplying the Object that implements that handler’s

interface. A feature is a setting that is either on

(true) or off (false). Several obvious examples come to

mind: namespace awareness and validation, for example.

SAX includes the methods needed for setting properties and

features in the XMLReader interface. This means you have to

change very little of your existing code to request validation, set

the namespace separator, and handle other feature and property

requests. The methods used for setting these properties and features

are outlined in Table

4-1.

For all of these, the ID of a specific property or feature is a URI. The standard set of features and properties is listed in the Appendix 0. Additionally, most parsers define additional, vendor-specific properties that their parser supports. For example, Apache Xerces defines quite a few additional features and properties, listed online at http://xml.apache.org/xerces2-j/features.html and http://xml.apache.org/xerces2-j/properties.html.

The most convenient aspect of these methods is that they allow simple addition and modification of properties and features. Although new or updated features will require a parser implementation to add supporting code, the method by which features and properties are accessed remains standard and simple; only a new URI need be defined. Regardless of the complexity (or obscurity) of new XML-related ideas, this robust set of four methods should be sufficient to allow parsers to implement the new ideas.

Error Handling

Invoking the setFeature()

and setProperty() methods can

result in SAXNotSupportedExceptions and SAXNotRecognizedExceptions.

Tip

Both of these are also in the org.xml.sax package.

The first, SAXNotSupportedException, indicates that the

parser “knows” about the feature or property but doesn’t support it.

This is commonly used when a standard property or feature is not yet

coded in (such as in alpha or beta versions of parsers). So invoking

setFeature("http://xml.org/sax/features/namespaces")

on a parser in development might result in a SAXNotSupportedException. The parser

recognizes the feature (and probably plans to support it at some

point), but doesn’t have the ability to perform the requested

processing.

The second exception, SAXNotRecognizedException, commonly occurs

when your code uses vendor-specific features and properties, and then

you switch out your parser implementations. The new implementation

won’t know anything about the other vendor’s features or properties,

and will throw a SAXNotRecognizedException.

You should always explicitly catch these exceptions so you can

report them, rather than treating them as just another generic

SAXException. Otherwise, you end up

losing valuable information about what happened in your code. This

means you may have to write a bit of extra code, but thus is the price

for good exception handling; here’s a slightly updated version of the

buildTree() method (detailed

originally in Chapter

3) that handles these problems gracefully:

public void buildTree(DefaultTreeModel treeModel,

DefaultMutableTreeNode base, String xmlURI)

throws IOException, SAXException {

String featureURI = "";

XMLReader reader = null;

try {

// Create instances needed for parsing

reader = XMLReaderFactory.createXMLReader();

JTreeHandler jTreeHandler =

new JTreeHandler(treeModel, base);

// Register content handler

reader.setContentHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Register error handler

reader.setErrorHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Turn on validation

featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/validation";

reader.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Turn on schema validation, as well

featureURI = "http://apache.org/xml/features/validation/schema";

reader.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Parse

InputSource inputSource = new InputSource(xmlURI);

reader.parse(inputSource);

} catch (SAXNotRecognizedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not recognize the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

} catch (SAXNotSupportedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not support the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

}

}Resolving Entities

You’ve already seen how to interact with content in the

XML document you’re parsing (using ContentHandler), and how to deal with error

conditions (ErrorHandler). Both of

these are concerned specifically with the data in an XML document. What

I haven’t talked about is the process by which the parser goes outside

of the document and gets data. For example, consider a simple entity

reference in an XML document:

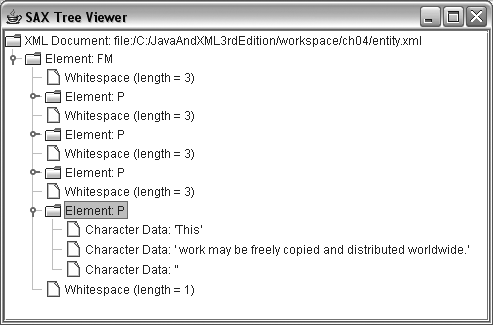

<FM> <P>Text placed in the public domain by Moby Lexical Tools, 1992.</P> <P>SGML markup by Jon Bosak, 1992-1994.</P> <P>XML version by Jon Bosak, 1996-1998.</P> <P>&usage-terms;</P> </FM>

Your schema then indicates to the parser how to resolve that entity:

<!ENTITY usage-terms

SYSTEM "http://www.newInstance.com/entities/usage-terms.xml">At parse time, the usage-terms

entity reference will be expanded (in this case, to “This work may be

freely copied and distributed worldwide.”, as seen in Figure 4-1).

However, there are several cases where you might not want this “default” behavior:

You don’t have network access, so you want the entity to resolve to a local copy of the referenced document (perhaps a version you’ve downloaded yourself).

You want to substitute your own content for the content specified in the schema.

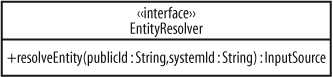

You can short-circuit normal entity resolution using org.xml.sax.EntityResolver. This interface does

exactly what it says: resolves entities. More important, it allows you

to get involved in the entity resolution process. The interface defines

only a single method, as shown in Figure 4-2.

To insert your own logic into the resolution process, create an

implementation of this interface, and register it with your XMLReader instance through setEntityResolver(). Once that’s done, every

time the reader comes across an entity reference, it passes the public

ID and system ID for that entity to the

resolveEntity() method of your EntityResolver implementation.

Typically, the XML reader resolves the entity through the

specified public or system ID. If you want to accept this default

behavior in your own EntityResolver

implementation, just return null from

your version of resolveEntity(). In

fact, you should always make sure that whatever code you add to your

resolveEntity() implementation, it

returns null in the default case. In

other words, start with an implementation class that looks like Example 4-1.

package javaxml3;

import java.io.IOException;

import org.xml.sax.EntityResolver;

import org.xml.sax.InputSource;

import org.xml.sax.SAXException;

public class SimpleEntityResolver implements EntityResolver {

public InputSource resolveEntity(String publicID, String systemID)

throws IOException, SAXException {

// In the default case, return null

return null;

}

}Of course, things are more interesting when you

don’t return null. If you return an InputSource from this method, that InputSource is used in resolution of the

entity reference, rather than the public or system ID specified in your

schema. In other words, you can specify your own data instead of letting

the reader handle resolution on its own. As an example, create a

usage-terms.xml file on your local machine:

Any use of this file could result in your <i>imminent</i> destruction. Consider yourself warned!

Now you can indicate that this file should be used via resolveEntity():

private static final String USAGE_TERMS_ID =

"http://www.newInstance.com/entities/usage-terms.xml";

private static final String USAGE_TERMS_LOCAL_URI =

"/your/path/to/usage-terms.xml";

public InputSource resolveEntity(String publicID, String systemID)

throws IOException, SAXException {

if (systemID.equals(USAGE_TERMS_ID)) {

return new InputSource(USAGE_TERMS_LOCAL_URI);

}

// In the default case, return null

return null;

}Tip

Be sure to change the USAGE_TERMS_LOCAL_URI to match your own

filesystem path.

You can see that instead of allowing resolution to the online

resource, an InputSource that

provides access to the local version of

copyright.xml is returned. If you recompile your

source file and run the tree viewer, you can visually verify that this

local copy is used.

You register this resolver on your

XMLReader via the setEntityResolver() method, as shown here

(using the SAXTreeViewer example

again):

// Register content handler reader.setContentHandler(jTreeHandler); // Register error handler reader.setErrorHandler(jTreeHandler); // Register entity resolver reader.setEntityResolver(new SimpleEntityResolver()); // Turn on validation featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/validation"; reader.setFeature(featureURI, true); // Turn on schema validation, as well featureURI = "http://apache.org/xml/features/validation/schema"; reader.setFeature(featureURI, true);

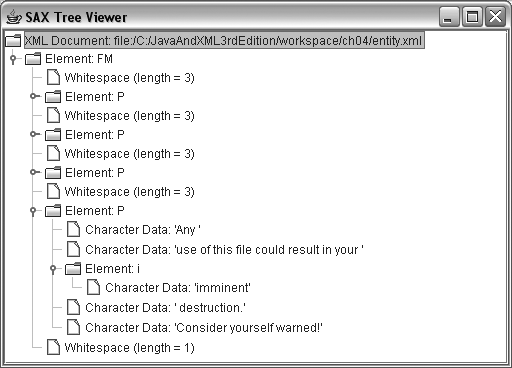

Figure 4-3

shows the usage-terms entity

reference expanded, using the local file, rather than the URI specified

in the schema.

In real-world applications, resolveEntity() tends to become a lengthy

laundry list of if/then/else

blocks, each one handling a specific system or public ID. And this brings up an important point: try to

avoid this method becoming a kitchen sink for IDs. If you no longer need

a specific resolution to occur, remove the if clause for it. Additionally, try to use

different EntityResolver implementations for different

applications, rather than creating one generic implementation for all

your applications. Doing this avoids code bloat, and more important,

speeds up entity resolution. If you have to wait for your reader to run

through 50 String.equals()

comparisons, you can really bog down an application. Be sure to put

references accessed often at the top of the if/else

stack, as well, so they are encountered first and result in quicker

entity resolution.

Finally, I want to make one more recommendation concerning your

EntityResolver implementations. You’ll notice

that I defined my implementation in a separate class file, while the

ErrorHandler, ContentHandler, and (as you’ll see in “Notations and

Unparsed Entities”) DTDHandler

implementations were in the same source file as parsing occurred in.

That wasn’t an accident! You’ll find that the way you deal with content,

errors, and DTDs is fairly static. You write your program, and that’s

it. When you make changes, you’re performing a larger code rewrite, so

recompiling your core parsing program is a given. However, you’ll make

many changes to the way you want your application to resolve entities.

Depending on the machine you’re on, the type of client you’re deploying

to, and what (and where) documents are available, you’ll often use

several different versions of an EntityResolver implementation. To allow for

rapid changes to this implementation without causing editing or

recompilation of your core parsing code, I use a separate source file

for EntityResolver implementations; I

suggest you do the same. And with that, you should know all that you

need to know about resolving entities in your applications using

SAX.

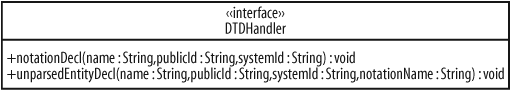

Notations and Unparsed Entities

After a rather extensive look at EntityResolver, I’m going to cruise through

DTDHandler (also in org.xml.sax). In almost nine years of

extensive SAX and XML programming, I’ve used this interface only once—in

writing JDOM (covered in Chapter 9)—and even

then, it was a rather obscure case. Still, if you work with unparsed

entities often, are into parser internals, or just want to get into

every nook and cranny of the SAX API, then you need to know about

DTDHandler. The interface is shown in

all its simplicity in Figure 4-4.

The DTDHandler interface allows

you to receive notification when a reader encounters an unparsed entity

or notation declaration. Of course, both of these events occur in

DTDs, not XML documents, which is why this is called DTDHandler. The two methods listed in Figure 4-4 do exactly

what you would expect. The first reports a notation declaration,

including its name, public ID, and system ID. Remember the NOTATION structure in DTDs? (Flip back to

Chapter 2 if

you’re unclear.)

<!NOTATION jpeg SYSTEM "images/jpeg">

The second method provides information about an unparsed entity declaration, which looks as follows:

<!ENTITY stars_logo SYSTEM "http://www.nhl.com/img/team/dal38.gif"

NDATA jpeg>In both cases, you can take action at these occurrences if you

create an implementation of DTDHandler and register it with your reader

through the XMLReader’s setDTDHandler() method. This is generally

useful when writing low-level applications that must either reproduce

XML content (such as an XML editor), or when you want to build up some

Java representation of a DTD’s constraints (such as in a data binding

implementation). In most other situations, it isn’t something you will

need very often.

The DefaultHandler Class

Because SAX is interface-driven, you have to do a lot

of tedious work to get started with an XML-based application. For

example, when you write your ContentHandler implementation, you have to

implement each and every method of that interface, even if you aren’t

inserting behavior into each callback. If you need an ErrorHandler, you add three more method

implementations; using DTDHandler?

That’s a few more. A lot of times, though, you’re writing lots of

no-operation methods, as you only need to interact with a couple of key

callbacks.

Fortunately, org.xml.sax.helpers.DefaultHandler can be a

real boon in these situations. This class doesn’t define any behavior of

its own; however, it does implement ContentHandler, ErrorHandler,

EntityResolver, and DTDHandler, and provides empty implementations

of each method of each interface. So you can have a single class (call

it, for example, MyHandlerClass) that

extends DefaultHandler. You then only

override the callback methods you’re concerned with. You might implement

startElement(), characters(), endElement(), and fatalError(), for example. In any

combination of implemented methods, though, you’ll save tons of lines of

code for methods you don’t need to provide action for, and make your

code a lot clearer too. Then, the argument to setErrorHandler(), setContentHandler(), and setDTDHandler() would be the same instance

of this MyHandlerClass.

Tip

You can pass a DefaultHandler

instance to setEntityResolver()

as well, although (as I’ve already said) I discourage mixing EntityResolver implementations in with these

other handlers.

Extension Interfaces

SAX provides several extension interfaces. These are interfaces that SAX parsers are not

required to support; you’ll find these interfaces in org.xml.sax.ext. In some cases, you’ll have to

download these directly from the SAX web site (http://www.saxproject.org),

although most parsers will include these in the parser download.

Warning

Because parsers aren’t required to support these handlers, never write code that absolutely depends on them, unless you’re sure you won’t be changing parser. If you can provide enhanced features, but fallback to standard SAX, you’re in a much better position.

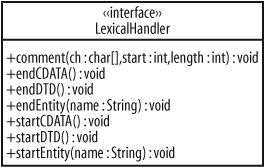

LexicalHandler

The first of these handlers is probably the most useful:

org.xml.sax.ext.LexicalHandler. This handler

provides methods that can receive notification of several lexical

events in an XML document, such as comments, entity declarations, DTD declarations, and CDATA sections. In ContentHandler, these lexical events are

essentially ignored, and you just get the data and declarations

without notification of when or how they were provided.

This is not really a general-use handler, as most applications

don’t need to know if text was in a CDATA section or not. However, if you are

working with an XML editor, serializer, or other component that must

know the exact format of the input document—and not just its

contents—then the LexicalHandler

can really help you out.

To see this guy in action, you first need to add an import statement for org.xml.sax.ext.LexicalHandler to your

SAXTreeViewer.java source file. Once that’s done,

you can add LexicalHandler to the

implements clause in the nonpublic

class JTreeContentHandler in that

source file:

class JTreeHandler implements ContentHandler, ErrorHandler, LexicalHandler {To get started, look at the first lexical event that might

happen in processing an XML document: the start and end of a

DTD reference or declaration. That triggers the startDTD() and endDTD() callbacks (I’ve coded up versions

appropriate for SAXTreeViewer

here):

public void startDTD(String name, String publicID,

String systemID)

throws SAXException {

DefaultMutableTreeNode dtdReference =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("DTD for '" + name + "'");

if (publicID != null) {

DefaultMutableTreeNode publicIDNode =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("Public ID: '" + publicID + "'");

dtdReference.add(publicIDNode);

}

if (systemID != null) {

DefaultMutableTreeNode systemIDNode =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("System ID: '" + systemID + "'");

dtdReference.add(systemIDNode);

}

current.add(dtdReference);

}

public void endDTD( ) throws SAXException {

// No action needed here

}This adds a visual cue when a DTD is encountered, and notes the

system ID and public ID of the DTD. Continuing on, there is a pair of

similar methods for entity references, startEntity() and endEntity(). These are triggered before

and after processing entity references. You can add a visual cue for

this event as well:

public void startEntity(String name) throws SAXException {

DefaultMutableTreeNode entity =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("Entity: '" + name + "'");

current.add(entity);

current = entity;

}

public void endEntity(String name) throws SAXException {

// Walk back up the tree

current = (DefaultMutableTreeNode)current.getParent( );

}This ensures that the content of, for example, the usage-terms entity reference is included

within an “Entity” tree node. Simple enough.

Next are two events for CDATA sections:

public void startCDATA( ) throws SAXException {

DefaultMutableTreeNode cdata =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("CDATA Section");

current.add(cdata);

current = cdata;

}

public void endCDATA( ) throws SAXException {

// Walk back up the tree

current = (DefaultMutableTreeNode)current.getParent( );

}This is old hat by now; the title element’s content now appears

as the child of a CDATA node. And

with that, only one method is left, which receives comment notification:

public void comment(char[] ch, int start, int length)

throws SAXException {

String comment = new String(ch, start, length);

DefaultMutableTreeNode commentNode =

new DefaultMutableTreeNode("Comment: '" + comment + "'");

current.add(commentNode);

}This method behaves just like the characters() and ignorableWhitespace() methods. Keep in

mind that only the text of the comment is reported to this method, not

the surrounding <!-- and --> delimiters.

Finally, register this handler with your XMLReader. Since the reader isn’t required to

support LexicalHandler, you can’t

just call setLexicalHandler();

instead, use setProperty():

// Register lexical handler

reader.setProperty("http://xml.org/sax/properties/lexical-handler",

jTreeHandler);With these changes in place, you can compile the example program and run it. You should get output similar to that shown in Figure 4-5.

Tip

Be sure you actually have some of these lexical events in your document before trying this out. I’ve added an entity reference and comment in the as_you-with_entity.xml file, included in the downloadable examples for this book (see http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/9780596101497).

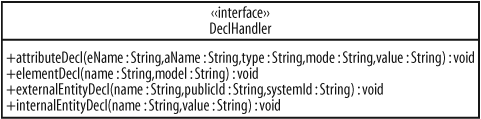

DeclHandler

A lesser used interface, DeclHandler is another of the extended SAX

interfaces. This interface defines methods that receive notification

of specific events within a DTD, such as element and attribute declarations. This is another item

only good for very specific cases; again, XML editors and components

that must know the exact lexical structure of documents and their DTDs

come to mind. I’m not going to show you an example of using the

DeclHandler; at this point you know

more than you’ll probably ever need to about handling callback

methods. Instead, I’ll just give you a look at the interface, shown in

Figure

4-6.

The DeclHandler interface is

fairly self-explanatory. The first two methods handle the <!ELEMENT> and <!ATTLIST> constructs. The third,

externalEntityDecl(), reports entity declarations (through <!ENTITY>) that refer to external

resources. The final method, internalEntityDecl(), reports entities

defined inline. That’s all there is to it.

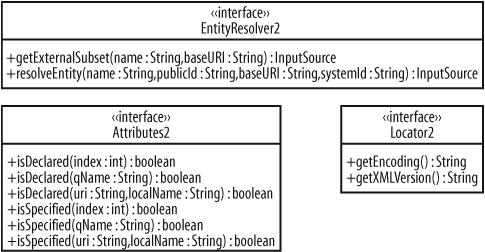

Attributes2, Locator2, and EntityResolver2

SAX provides three other interesting interfaces

in org.xml.sax.ext: Attributes2, Locator2 , and EntityResolver2. These all extend their

respective core interfaces from org.xml.sax (Attributes, Locator, and EntityResolver), and class diagrams are

shown for all three in Figure 4-7.

These interfaces provide additional information for use in

parsing, ranging from whether an attribute was specified in a DTD to

the encoding of an XML document (pulled from the XML declaration). You

can find out if your parser supports and uses these extensions via

the getFeature()

method:

// Check for Attributes2 usage featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/use-attributes2"; jTreeHandler.setUsingAttributes2(reader.getFeature(featureURI)); // Check for Locator2 usage featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/use-locator2"; jTreeHandler.setUsingLocator2(reader.getFeature(featureURI));

Tip

These and all other SAX-standard feature and property URIs are detailed in the Appendix.

Unfortunately, most parsers don’t support these extensions, so any sort of detailed coverage of them is infeasible. I could show you how they behave under lesser-used parsers that support them, but that’s hardly helpful when you move to more mainstream parsers like Apache Xerces. If you are interested in these extensions, check out the SAX Javadoc at http://www.saxproject.org/apidoc/org/xml/sax/ext/package-summary.html, and hope that by the next revision of this book, these will be more commonly supported (and then I’ll spend some time on them!).

Tip

For those who want the fullest in SAX features, you should check out AElfred2 and the GNU JAXP project, online at http://www.gnu.org/software/classpathx/jaxp. I prefer to use Xerces for production work, but your mileage may vary.

Filters and Writers

At this point, I want to diverge from the beaten path. There are a lot of additional features in SAX that can really turn you into a power developer, and take you beyond the confines of “standard” SAX. In this section, I’ll introduce you to two of these: SAX filters and writers. Using classes both in the standard SAX distribution and available separately from the SAX web site (http://www.saxproject.org), you can add some fairly advanced behavior to your SAX applications. This will also get you in the mindset of using SAX as a pipeline of events, rather than a single layer of processing.

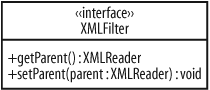

XMLFilters

First on the list is the org.xml.sax.XMLFilter class that comes in

the basic SAX download, and should be included with any parser

distribution supporting SAX 2. This class extends the XMLReader interface, and adds two new

methods to that class, as shown in Figure 4-8.

It might not seem like there is much to say here; what’s the big

deal, right? Well, by allowing a hierarchy of XMLReaders through this filtering mechanism,

you can build up a processing chain, or

pipeline, of events. To understand what I

mean by a pipeline, you first need to understand the normal flow of a SAX parse:

Events in an XML document are passed to the SAX reader.

The SAX reader and registered handlers pass events and data to an application.

What developers started realizing, though, is that it is simple to insert one or more additional links into this chain:

Events in an XML document are passed to the SAX reader.

The SAX reader performs some processing and passes information to another SAX reader.

Repeat until all SAX processing is done.

Finally, the SAX reader and registered handlers pass events and data to an application.

It’s the middle two steps that create a pipeline, where one

reader that performed specific processing passes its information on to

another reader, repeatedly, instead of having to lump all code into

one reader. When this pipeline is set up with multiple readers,

modular and efficient programming results. And that’s what the

XMLFilter class allows for: chaining of

XMLReader implementations through filtering.

Enhancing this even further is the class org.xml.sax.helpers.XMLFilterImpl, which

provides a simple implementation of XMLFilter. It is the convergence of an

XMLFilter and the DefaultHandler class: the XMLFilterImpl class implements XMLFilter, ContentHandler, ErrorHandler, EntityResolver, and DTDHandler, providing pass-through versions

of each method of each handler. In other words, it sets up a pipeline

for all SAX events, allowing your code to override any methods that

need to insert processing into the pipeline.

Again, it’s best to see these in action. Example 4-2 is a working, ready-to-use filter. You’re past the basics, so I’m going to move through this rapidly.

package javaxml3;

import org.xml.sax.Attributes;

import org.xml.sax.SAXException;

import org.xml.sax.XMLReader;

import org.xml.sax.helpers.XMLFilterImpl;

public class NamespaceFilter extends XMLFilterImpl {

/** The old URI, to replace */

private String oldURI;

/** The new URI, to replace the old URI with */

private String newURI;

public NamespaceFilter(XMLReader reader,

String oldURI, String newURI) {

super(reader);

this.oldURI = oldURI;

this.newURI = newURI;

}

public void startPrefixMapping(String prefix, String uri)

throws SAXException {

// Change URI, if needed

if (uri.equals(oldURI)) {

super.startPrefixMapping(prefix, newURI);

} else {

super.startPrefixMapping(prefix, uri);

}

}

public void startElement(String uri, String localName,

String qName, Attributes attributes)

throws SAXException {

// Change URI, if needed

if (uri.equals(oldURI)) {

super.startElement(newURI, localName, qName, attributes);

} else {

super.startElement(uri, localName, qName, attributes);

}

}

public void endElement(String uri, String localName, String qName)

throws SAXException {

// Change URI, if needed

if (uri.equals(oldURI)) {

super.endElement(newURI, localName, qName);

} else {

super.endElement(uri, localName, qName);

}

}

}Start out by extending XMLFilterImpl, so you don’t have to worry

about any events that you don’t want to deal with (like DefaultHandler, you’ll get no-op methods

“for free”); the XMLFilterImpl

class takes care of them by passing on all events unchanged unless a

method is overridden. All that’s left, in this example, is to change a

namespace URI from an old one, to a new one.

Tip

If this example seems trivial, don’t underestimate its

usefulness. Many times in the last several years, the URI of a

namespace for a specification (such as XML Schema or XSLT) has

changed. Rather than having to hand-edit all of my XML documents or

write code for XML that I receive, this NamespaceFilter takes care of the problem

for me.

Passing an XMLReader instance

to the constructor sets that reader as its parent, so the parent

reader receives any events passed on from the filter (which is all

events, by virtue of the XMLFilterImpl class, unless the NamespaceFilter class overrides that

behavior). By supplying two URIs—the URI to be replaced, and the URI

to replace that old one with—your filter is ready to use. The three

overridden methods handle any needed interchanging of that URI. Once

you have a filter like this in place, you supply a reader to it, and

then operate upon the filter, not the

reader. For example, suppose that the SAXTreeViewer application is used to display

XML versions of O’Reilly books, and the O’Reilly namespace URI for

these books is universally being changed from http://www.oreilly.com to http://safari.oreilly.com. In that case, you

could use the filter like this:

public void buildTree(DefaultTreeModel treeModel,

DefaultMutableTreeNode base, String xmlURI)

throws IOException, SAXException {

String featureURI = "";

XMLReader reader = null;

try {

// Create instances needed for parsing

reader = XMLReaderFactory.createXMLReader();

JTreeHandler jTreeHandler =

new JTreeHandler(treeModel, base);

NamespaceFilter filter = new NamespaceFilter(reader,

"http://www.oreilly.com",

"http://safari.oreilly.com");

// Register content handler

filter.setContentHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Register error handler

filter.setErrorHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Register entity resolver

filter.setEntityResolver(new SimpleEntityResolver());

// Register lexical handler

filter.setProperty("http://xml.org/sax/properties/lexical-handler",

jTreeHandler);

// Turn on validation

featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/validation";

filter.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Turn on schema validation, as well

featureURI = "http://apache.org/xml/features/validation/schema";

filter.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Parse

InputSource inputSource = new InputSource(xmlURI);

filter.parse(inputSource);

} catch (SAXNotRecognizedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not recognize the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

} catch (SAXNotSupportedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not support the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

}

}Of course, you can chain these filters together as well, and use them as standard libraries. When I’m dealing with older XML documents, I often create several of these with old XSL and XML Schema URIs and put them in place so I don’t have to worry about incorrect URIs:

XMLReader reader = XMLReaderFactory.createXMLReader(vendorParserClass);

NamespaceFilter xslFilter = new NamespaceFilter(reader,

"http://www.w3.org/TR/XSL",

"http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform");

NamespaceFilter xsdFilter = new NamespaceFilter(xslFilter,

"http://www.w3.org/TR/XMLSchema",

"http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema");Here, I’m building a longer pipeline to ensure that no old namespace URIs sneak by and cause my applications any trouble.

Warning

Be careful not to build too long a pipeline; each new link in the chain adds some processing time. All the same, this is a great way to build reusable components for SAX.

XMLWriter

Now that you understand how filters work in SAX, I want to

introduce you to a specific filter,

XMLWriter. This class, as well its subclass,

DataWriter, can be downloaded from

David Megginson’s site at http://www.megginson.com/Software.

Tip

David Megginson shepherded SAX through its early days and has

now returned to the fold. David is a SAX guru, and even though he no

longer actively works on XMLWriter (or DataWriter), he has created some

incredibly useful classes, and still hosts them on his personal web

site.

XMLWriter extends XMLFilterImpl, and

DataWriter extends XMLWriter. Both of these filter classes are

used to output XML, which may seem a bit at odds with what you’ve

learned so far about SAX. However, it’s not that unusual; you could

easily insert statements into a startElement() or characters() callback that fires up a

java.io.Writer and outputs to it.

In fact, that’s awfully close to what XMLWriter and DataWriter do.

I’m not going to spend a lot of time on this class, because it’s

not really the way you want to be outputting XML in the general sense;

it’s much better to use DOM, JDOM, or another XML API if you want

mutability. However, the XMLWriter

class offers a valuable way to inspect what’s going on in a SAX

pipeline. By inserting it between other filters and

readers in your pipeline, it can be used to output a snapshot of your

data.

For example, in the case where you’re changing namespace URIs, it might be that you want to actually

store the XML document with the new namespace URI (be it a modified

O’Reilly URI, an updated XSL URI, or whatever other use-case you come

up with). This is a piece of cake with the XMLWriter class. Since you’ve already got

SAXTreeViewer using the NamespaceFilter, I’ll use that as an

example. First, add import

statements for java.io.Writer (for output), and the com.megginson.sax.XMLWriter class. Once

that’s in place, you’ll need to insert an instance of XMLWriter between the NamespaceFilter and the XMLReader instances; this means output will

occur after namespaces have been changed but before the visual events

occur:

public void buildTree(DefaultTreeModel treeModel,

DefaultMutableTreeNode base, String xmlURI)

throws IOException, SAXException {

String featureURI = "";

XMLReader reader = null;

try {

// Create instances needed for parsing

reader = XMLReaderFactory.createXMLReader();

JTreeHandler jTreeHandler =

new JTreeHandler(treeModel, base);

XMLWriter writer = new XMLWriter(reader, new FileWriter("snapshot.xml"));

NamespaceFilter filter = new NamespaceFilter(writer,

"http://www.oreilly.com",

"http://safari.oreilly.com");

// Register content handler

filter.setContentHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Register error handler

filter.setErrorHandler(jTreeHandler);

// Register entity resolver

filter.setEntityResolver(new SimpleEntityResolver());

// Register lexical handler

filter.setProperty("http://xml.org/sax/properties/lexical-handler",

jTreeHandler);

// Turn on validation

featureURI = "http://xml.org/sax/features/validation";

filter.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Turn on schema validation, as well

featureURI = "http://apache.org/xml/features/validation/schema";

filter.setFeature(featureURI, true);

// Parse

InputSource inputSource = new InputSource(xmlURI);

filter.parse(inputSource);

} catch (SAXNotRecognizedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not recognize the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

} catch (SAXNotSupportedException e) {

System.err.println("The parser class " + reader.getClass().getName() +

" does not support the feature URI '" + featureURI + "'");

System.exit(-1);

}

}Tip

Be sure you set the parent of the NamespaceFilter instance to be the

XMLWriter, not the XMLReader. Otherwise, no output will

actually occur.

Once you’ve got these changes compiled in, run the example. You

should get a snapshot.xml file created in the

directory from which you’re running the example. Both XMLWriter and DataWriter offer a lot more in terms of

methods to output XML, both in full and in part, and you should check

out the Javadoc included with the downloaded package.

Get Java and XML, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.