Chapter 1. Operators Teach Kubernetes New Tricks

An Operator is a way to package, run, and maintain a Kubernetes application. A Kubernetes application is not only deployed on Kubernetes, it is designed to use and to operate in concert with Kubernetes facilities and tools.

An Operator builds on Kubernetes abstractions to automate the entire lifecycle of the software it manages. Because they extend Kubernetes, Operators provide application-specific automation in terms familiar to a large and growing community. For application programmers, Operators make it easier to deploy and run the foundation services on which their apps depend. For infrastructure engineers and vendors, Operators provide a consistent way to distribute software on Kubernetes clusters and reduce support burdens by identifying and correcting application problems before the pager beeps.

Before we begin to describe how Operators do these jobs, let’s define a few Kubernetes terms to provide context and a shared language to describe Operator concepts and components.

How Kubernetes Works

Kubernetes automates the lifecycle of a stateless application, such as a static web server. Without state, any instances of an application are interchangeable. This simple web server retrieves files and sends them on to a visitor’s browser. Because the server is not tracking state or storing input or data of any kind, when one server instance fails, Kubernetes can replace it with another. Kubernetes refers to these instances, each a copy of an application running on the cluster, as replicas.

A Kubernetes cluster is a collection of computers, called nodes. All cluster work runs on one, some, or all of a cluster’s nodes. The basic unit of work, and of replication, is the pod. A pod is a group of one or more Linux containers with common resources like networking, storage, and access to shared memory.

Note

The Kubernetes pod documentation is a good starting point for more information about the pod abstraction.

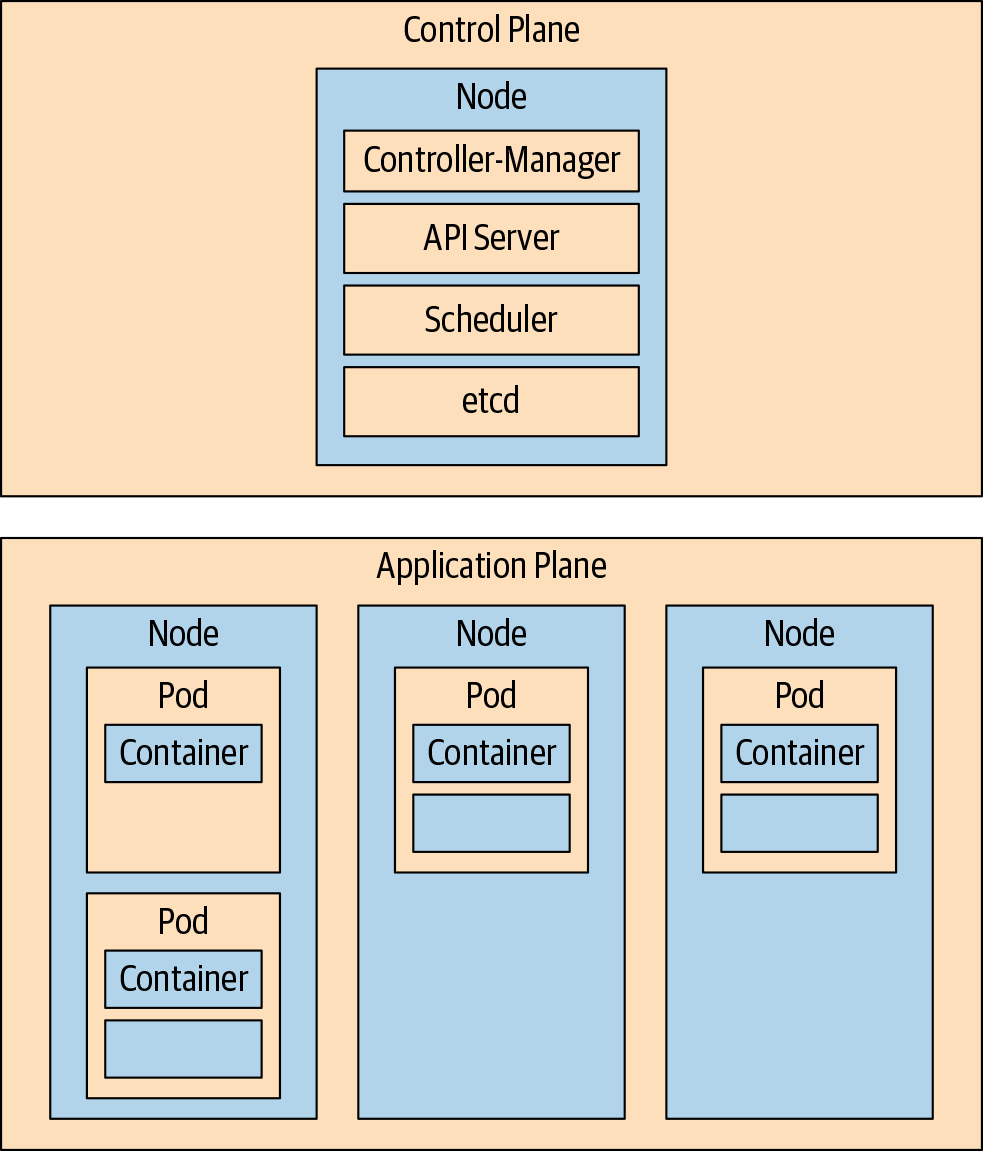

At a high level, a Kubernetes cluster can be divided into two planes. The control plane is, in simple terms, Kubernetes itself. A collection of pods comprises the control plane and implements the Kubernetes application programming interface (API) and cluster orchestration logic.

The application plane, or data plane, is everything else. It is the group of nodes where application pods run. One or more nodes are usually dedicated to running applications, while one or more nodes are often sequestered to run only control plane pods. As with application pods, multiple replicas of control plane components can run on multiple controller nodes to provide redundancy.

The controllers of the control plane implement control loops that repeatedly compare the desired state of the cluster to its actual state. When the two diverge, a controller takes action to make them match. Operators extend this behavior. The schematic in Figure 1-1 shows the major control plane components, with worker nodes running application workloads.

While a strict division between the control and application planes is a convenient mental model and a common way to deploy a Kubernetes cluster to segregate workloads, the control plane components are a collection of pods running on nodes, like any other application. In small clusters, control plane components are often sharing the same node or two with application workloads.

The conceptual model of a cordoned control plane isn’t quite so tidy, either. The kube let agent running on every node is part of the control plane, for example. Likewise, an Operator is a type of controller, usually thought of as a control plane component. Operators can blur this distinct border between planes, however. Treating the control and application planes as isolated domains is a helpful simplifying abstraction, not an absolute truth.

Figure 1-1. Kubernetes control plane and worker nodes

Example: Stateless Web Server

Since you haven’t set up a cluster yet, the examples in this chapter are more like terminal excerpt “screenshots” that show what basic interactions between Kubernetes and an application look like. You are not expected to execute these commands as you are those throughout the rest of the book. In this first example, Kubernetes manages a relatively simple application and no Operators are involved.

Consider a cluster running a single replica of a stateless, static web server:

$ kubectl get pods>

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

staticweb-69ccd6d6c-9mr8l 1/1 Running 0 23s

After declaring there should be three replicas, the cluster’s actual state differs from the desired state, and Kubernetes starts two new instances of the web server to reconcile the two, scaling the web server deployment:

$ kubectl scale deployment staticweb --replicas=3 $ kubectl get pods NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE staticweb-69ccd6d6c-4tdhk 1/1 Running06s staticweb-69ccd6d6c-9mr8l 1/1 Running0100s staticweb-69ccd6d6c-m9qc7 1/1 Running06s

Deleting one of the web server pods triggers work in the control plane to restore the desired state of three replicas. Kubernetes starts a new pod to replace the deleted one. In this excerpt, the replacement pod shows a STATUS of ContainerCreating:

$ kubectl delete pod staticweb-69ccd6d6c-9mr8l $ kubectl get pods NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE staticweb-69ccd6d6c-4tdhk 1/1 Running02m8s staticweb-69ccd6d6c-bk27p 0/1 ContainerCreating014s staticweb-69ccd6d6c-m9qc7 1/1 Running02m8s

This static site’s web server is interchangeable with any other replica, or with a new pod that replaces one of the replicas. It doesn’t store data or maintain state in any way. Kubernetes doesn’t need to make any special arrangements to replace a failed pod, or to scale the application by adding or removing replicas of the server.

Stateful Is Hard

Most applications have state. They also have particulars of startup, component interdependence, and configuration. They often have their own notion of what “cluster” means. They need to reliably store critical and sometimes voluminous data. Those are just three of the dimensions in which real-world applications must maintain state. It would be ideal to manage these applications with uniform mechanisms while automating their complex storage, networking, and cluster connection requirements.

Kubernetes cannot know all about every stateful, complex, clustered application while also remaining general, adaptable, and simple. It aims instead to provide a set of flexible abstractions, covering the basic application concepts of scheduling, replication, and failover automation, while providing a clean extension mechanism for more advanced or application-specific operations. Kubernetes, on its own, does not and should not know the configuration values for, say, a PostgreSQL database cluster, with its arranged memberships and stateful, persistent storage.

Operators Are Software SREs

Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) is a set of patterns and principles for running large systems. Originating at Google, SRE has had a pronounced influence on industry practice. Practitioners must interpret and apply SRE philosophy to particular circumstances, but a key tenet is automating systems administration by writing software to run your software. Teams freed from rote maintenance work have more time to create new features, fix bugs, and generally improve their products.

An Operator is like an automated Site Reliability Engineer for its application. It encodes in software the skills of an expert administrator. An Operator can manage a cluster of database servers, for example. It knows the details of configuring and managing its application, and it can install a database cluster of a declared software version and number of members. An Operator continues to monitor its application as it runs, and can back up data, recover from failures, and upgrade the application over time, automatically. Cluster users employ kubectl and other standard tools to work with Operators and the applications they manage, because Operators extend Kubernetes.

How Operators Work

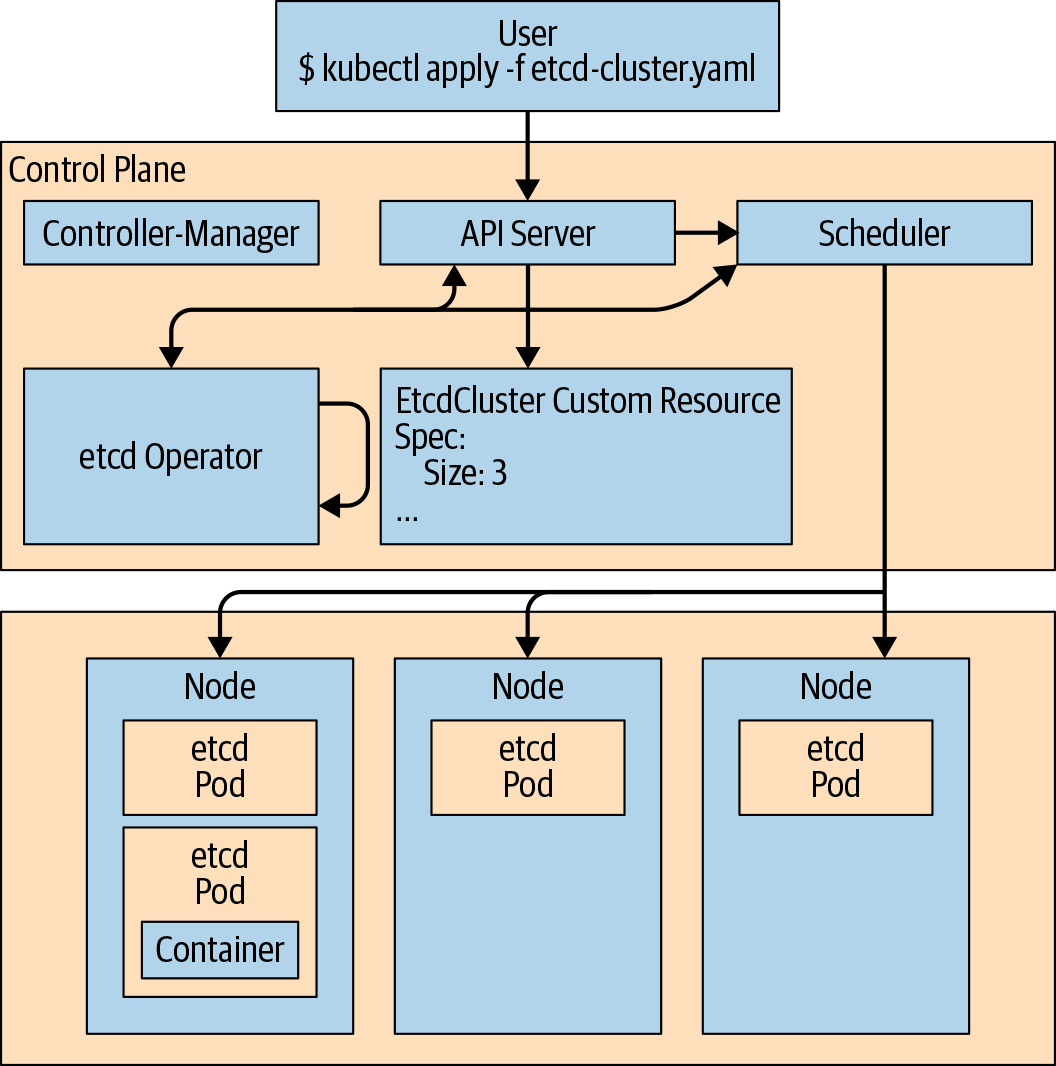

Operators work by extending the Kubernetes control plane and API. In its simplest form, an Operator adds an endpoint to the Kubernetes API, called a custom resource (CR), along with a control plane component that monitors and maintains resources of the new type. This Operator can then take action based on the resource’s state. This is illustrated in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. Operators are custom controllers watching a custom resource

Kubernetes CRs

CRs are the API extension mechanism in Kubernetes. A custom resource definition (CRD) defines a CR; it’s analogous to a schema for the CR data. Unlike members of the official API, a given CRD doesn’t exist on every Kubernetes cluster. CRDs extend the API of the particular cluster where they are defined. CRs provide endpoints for reading and writing structured data. A cluster user can interact with CRs with kubectl or another Kubernetes client, just like any other API resource.

How Operators Are Made

Kubernetes compares a set of resources to reality; that is, the running state of the cluster. It takes actions to make reality match the desired state described by those resources. Operators extend that pattern to specific applications on specific clusters. An Operator is a custom Kubernetes controller watching a CR type and taking application-specific actions to make reality match the spec in that resource.

Making an Operator means creating a CRD and providing a program that runs in a loop watching CRs of that kind. What the Operator does in response to changes in the CR is specific to the application the Operator manages. The actions an Operator performs can include almost anything: scaling a complex app, application version upgrades, or even managing kernel modules for nodes in a computational cluster with specialized hardware.

Example: The etcd Operator

etcd is a distributed key-value store. In other words, it’s a kind of lightweight database cluster. An etcd cluster usually requires a knowledgeable administrator to manage it. An etcd administrator must know how to:

-

Join a new node to an etcd cluster, including configuring its endpoints, making connections to persistent storage, and making existing members aware of it.

-

Back up the etcd cluster data and configuration.

-

Upgrade the etcd cluster to new etcd versions.

The etcd Operator knows how to perform those tasks. An Operator knows about its application’s internal state, and takes regular action to align that state with the desired state expressed in the specification of one or more custom resources.

As in the previous example, the shell excerpts that follow are illustrative, and you won’t be able to execute them without prior setup. You’ll do that setup and run an Operator in Chapter 2.

The Case of the Missing Member

Since the etcd Operator understands etcd’s state, it can recover from an etcd cluster member’s failure in the same way Kubernetes replaced the deleted stateless web server pod in our earlier example. Assume there is a three-member etcd cluster managed by the etcd Operator. The Operator itself and the etcd cluster members run as pods:

$ kubectl get pods NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE etcd-operator-6f44498865-lv7b9 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-cpnwr62qgl 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-fff78tmpxr 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-lrlk7xwb2k 1/1 Running01h

Deleting an etcd pod triggers a reconciliation, and the etcd Operator knows how to recover to the desired state of three replicas—something Kubernetes can’t do alone. But unlike with the blank-slate restart of a stateless web server, the Operator has to arrange the new etcd pod’s cluster membership, configuring it for the existing endpoints and establishing it with the remaining etcd members:

$ kubectl delete pod example-etcd-cluster-cpnwr62qgl $ kubectl get pods NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE etcd-operator-6f44498865-lv7b9 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-fff78tmpxr 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-lrlk7xwb2k 1/1 Running01h example-etcd-cluster-r6cb8g2qqw 0/1 PodInitializing04s

The etcd API remains available to clients as the Operator repairs the etcd cluster. In Chapter 2, you’ll deploy the etcd Operator and put it through its paces while using the etcd API to read and write data. For now, it’s worth remembering that adding a member to a running etcd cluster isn’t as simple as just running a new etcd pod, and the etcd Operator hides that complexity and automatically heals the etcd cluster.

Who Are Operators For?

The Operator pattern arose in response to infrastructure engineers and developers wanting to extend Kubernetes to provide features specific to their sites and software. Operators make it easier for cluster administrators to enable, and developers to use, foundation software pieces like databases and storage systems with less management overhead. If the “killernewdb” database server that’s perfect for your application’s backend has an Operator to manage it, you can deploy killernewdb without needing to become an expert killernewdb DBA.

Application developers build Operators to manage the applications they are delivering, simplifying the deployment and management experience on their customers’ Kubernetes clusters. Infrastructure engineers create Operators to control deployed services and systems.

Operator Adoption

A wide variety of developers and companies have adopted the Operator pattern, and there are already many Operators available that make it easier to use key services as components of your applications. CrunchyData has developed an Operator that manages PostgreSQL database clusters. There are popular Operators for MongoDB and Redis. Rook manages Ceph storage on Kubernetes clusters, while other Operators provide on-cluster management of external storage services like Amazon S3.

Moreover, Kubernetes-based distributions like Red Hat’s OpenShift use Operators to build features atop a Kubernetes core, keeping the OpenShift web console available and up to date, for example. On the user side, OpenShift has added mechanisms for point-and-click Operator installation and use in the web console, and for Operator developers to hook into the OperatorHub.io, discussed in Chapter 8 and Chapter 10.

Let’s Get Going!

Operators need a Kubernetes cluster to run on. In the next chapter we’ll show you a few different ways to get access to a cluster, whether it’s a local virtual Kubernetes on your laptop, a complete installation on some number of nodes, or an external service. Once you have admin access to a Kubernetes cluster, you will deploy the etcd Operator and see how it manages an etcd cluster on your behalf.

Get Kubernetes Operators now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.