Chapter 4. Leading Others

Leading through service to others is a major tenet of Lean leadership. In this chapter, we’ll explore the complementary relationship between servant leadership and Lean leadership, which means giving yourself over into the service of others. A servant leader fully acknowledges and accepts the responsibility to develop, support, enable, and encourage others on their path to serve and lead. This is a major tenet of Lean leadership philosophy. We’ll also look at the two pillars of The Toyota Way—respect for others and continuous improvement—as well as how you can use the Toyota Business Practices (TBP) problem-solving technique in conjunction with on-the-job development (OJD) to develop aspiring leaders.

Defining Servant Leadership for the 21st Century

Servant leadership is focused on empowering and helping others become the best they can possibly be in all facets of their life, from a professional, social, physical, mental, intellectual, and spiritual perspective. The values of The Toyota Way are all brought to life and supported through the practice of servant leadership:

-

Continuous improvement through the spirit of challenge and a bias toward action by going to the place where work is performed (the gemba) and respecting people by being inclusive

-

Taking responsibility

-

Acting with humility, dignity, honor, and integrity

The Toyota Way and servant leadership are complementary leadership philosophies: Lean leaders are inherently servant leaders, first and foremost.

Lean servant leaders are acutely focused on serving those they lead, as well as the Lean enterprise, instead of acquiring power or taking control. They attempt to continuously improve the people, processes, and technologies that are all around them. That means putting the needs of others before your own by empowering them and helping them to develop and perform at increasingly greater levels of competency and productivity, as well as improving their overall quality of life.

However, being a Lean servant leader doesn’t mean you become an indentured servant. On the contrary, it means your focus is on learning to develop yourself, in addition to enabling those around you, through mentoring, coaching, supporting, and empowerment. Ultimately, what you’re trying to create and foster is a collaborative, supportive, empathetic, engaging, and developmental relationship with those you lead—without implying that you’re subservient to them. After all, your followers must take responsibility for their development and learning processes as well, which sets them on their path to becoming a Lean servant leader.

Origins of Servant Leadership

Servant leadership is not new. The term was coined by Robert K. Greenleaf (a well-known leadership and management consultant active from the 1950s to 1990) and first published in an essay in 1970.1 Greenleaf was inspired by reading Hermann Hesse’s The Journey to the East.2 In Hesse’s story, a band of men on a mythical journey are accompanied by a servant named Leo. Through his incredible presence, Leo becomes the lifeblood of the group. He looks after, entertains, and sustains the men. One day, however, Leo disappears, and the men abandon their journey, because he was such a vital part of it; they no longer believe they can continue on their own. Some years later, the narrator loses his way. As he wanders in the desert without purpose, he’s fortunate enough to be taken in by an Order, only to find that Leo, whom he had first known as a servant, is their leader. He is their guiding spirit, a great and noble leader himself.

To Greenleaf, this story exemplifies that “The great leader is seen as a servant first, and that simple fact is the key to his [or her] greatness.”3 Leo’s inherent desire and ability to serve is what made him a great leader. Leo genuinely enjoyed helping others grow and flourish, both individually and as a team. And in his joy to serve, his leadership abilities sprung forth. In response to the evident servant stature leaders must possess, Greenleaf later went on to say:

Rather, they will freely respond only to individuals who are chosen as leaders because they are proven and trusted as servants. To the extent that this principle prevails in the future, the only truly viable institutions will be those that are predominantly servant-led. I am mindful of the long road ahead before these trends, which I see so clearly, become a major society-shaping force. We are not there yet. But I see encouraging movement on the horizon.4

Characteristics of Servant Leadership

Being a servant leader is defined by how you behave, think, act, and feel. Being of service to others is what motivates you to act. It’s a selfless way of life that’s based on building a vision that your followers can see and buy into to accomplish a mission that serves the greater good of the company, society, and even the world. Servant leadership can be summarized by three main qualities:

- Integrity

- Servant leaders lead with integrity, and their reputation for being morally honest and forthright, as well as for being true to their word, is an all-important and defining trait.

- Continuous interaction

- Servant leaders constantly work with those around them to foster and encourage their development as leaders because they genuinely care about others. Building and sustaining healthy relationships is very important to them, because they possess a strong sense of self-awareness and of the direction they want their lives to go in. Through their actions and behaviors, they lead by example, modeling behaviors they are looking for from their followers.

- Diversity

- Servant leaders cherish the diversity that life brings and value others’ ability to contribute. They recognize that different backgrounds and educational and life experiences provide for a variety of opinions and points of view, adding to the value of their interactions, as well as to the results their teams can accomplish. Diversity is good! It renders more creative solutions.

Servant leaders see their goals clearly and can communicate them well to others through their actions and words, thereby inspiring, motivating, and transforming others to act. A servant leader’s power is informal, gained or generated through influence, inspiration, or expertise in a field or area of knowledge, and achieved through instinctively having a bias toward action when it comes to that vision. As the famous Chinese general Sun Tzu stated in his classic treatise on war, The Art of War (written around 500 BC), “A leader leads by example, not by force.”5 The philosopher Lao-Tzu expressed a similar idea in the Tao Te Ching (fourth century BC): “A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.” That is the mark of a true servant leader.

Why Servant Leaders Are So Important to the Lean Enterprise

Lean servant leaders exist in sharp contrast to managers who possess formal power, which is something bestowed on them through a formal title and/or position within an organization. Managers have the responsibility of setting goals, communicating policies and status, coordinating work both within and among the teams, and providing the resources team members need to get the work done. They are responsible for managing the “work to a specific goal or outcome,” acting as the linchpin that connects the team, senior leadership, and the organization.

The world needs both servant leaders and managers. However, you can be a manager without being a servant leader. In contrast, servant leaders often do not possess any formal positional power, even though they can be influential within an organization and make major contributions to its success. The mark of a servant leader who evolves from a manager is measured by their ability to play both roles, allowing the organization to naturally evolve from a controlling, authoritative system to a consultative, service-oriented one in which everyone participates and contributes to achieving its mission, vision, and value proposition. This is a crucial inflection point for the Lean enterprise as it continues to change and evolve under the watchful eyes of its Lean servant leaders.

Lean servant leadership is one of the most effective leadership styles for modern businesses because it is results-driven and also forms a meaningful bond of trust and respect between leaders and their teams, as the constant cycle of development, feedback, and learning happens over and over again. In their willingness to serve, these leaders naturally play the role of teachers, mentors, and coaches who create a safe space in which problem solving through listening, observing, experimentation, and learning from mistakes is not only acceptable but encouraged. The most highly skilled parts of our 21st-century workforce respond favorably to this type of leadership style.

These workforce members value inclusion, being challenged, and learning above all else. They are not motivated by a paycheck; instead, it is the intrinsic things that inspire and promote creativity and ingenuity. They refuse to be micromanaged through command-and-control leadership styles, seeking autonomy and a purpose to their life’s work. And because of their skills and abilities, if they do not feel supported, empowered, and fulfilled in their current role, throughout their careers they will find it very easy to change employers. It is imperative that 21st century leaders understand this paradigm shift, because this highly skilled part of our workforce will continue to seek out and want to work for leaders who possess Lean servant leadership skills.

As a result, both the face of leadership and followership must change to meet this new 21st-century workplace dynamic. Thus the focus for you as a Lean servant leader must be on winning the loyalty of these highly skilled workers by inspiring, supporting, and developing them to give them everything they need to create and deliver innovative products/services, as well as to feel fulfilled, motivated, and valued by those they serve. Progressive companies understand this shift to support, encourage, and develop Lean servant leaders.

Becoming a Lean Servant Leader

Some people misinterpret the role when they hear the word “servant,” thinking that servant leaders are pushovers. On the contrary, being a Lean servant leader is about asking the tough questions and challenging those around you to push themselves to achieve success in whatever they undertake. Your role is to help through good times and difficult ones, offering whatever assistance and support you can to get things moving again.

So how do you go about developing the skills that servant leaders need? Here are a few tips to help you get started.

Develop your True North

Before you can become any type of leader, you first must develop an awareness of the purpose for your life and career. By taking the time to define and develop your convictions around what you intend to accomplish, you build your path forward. Self-reflection and asking for feedback from others are two great tools to define and chart your True North. Spending some time writing down all the things you want to accomplish in your life goes a long way toward identifying and defining your life’s purpose. As a Lean leader, you must proactively chart your course before someone else does it for you.

John Goddard (explorer, writer, and founder of the Goddard School) decided at the age of 16 to sit down and write out a lifetime to-do list,6 similar to the concept of today’s bucket list. Throughout his life, he diligently worked to accomplish the things on his list, stating that it gave him purpose and direction, acting as his personal True North. I, too, did the same at about his age, and when I finished it, I folded it up and tucked it away in a scrapbook of pictures and keepsakes from that same year, thinking that would be a good place to keep it safe.

Last year, when I was in the process of packing for a move, the list dropped out of that scrapbook. Immediately, I knew exactly what it was, and for a brief second, I thought to myself, “Do I even want to open it up?” I hadn’t looked at it in a very, very long time, but my curiosity got the best of me. I was amazed (actually, “shocked” would be a better word) that when I tallied up what I had accomplished to date in my lifetime, it amounted to about 75% of what I had written down many decades ago. Keep in mind that thoughts are things and writing crystalizes your thoughts, turning them into action. All of those things have been with me, in the back of my mind, as I’ve progressed through my life. My subconscious mind had taken them in and committed them to memory. And yes, becoming an author was on that list.

So as you work to chart out your True North, ask yourself:

-

Do you know what you want to accomplish?

-

Are you proud of what you have accomplished in your life to date?

-

If someone asked you to state your life’s purpose or value proposition, how would you answer them?

Lean servant leaders help others to discover their True North. Ask those you mentor or coach to spend some time thinking about and writing down their lifetime to-do lists. If they have such a list already, ask them how you can help them accomplish these things. I think you’ll be amazed at the drive and purpose such a list creates in both you and your followers. Checking things off your list can be very motivating and can drive your desire to achieve greater and more complicated things in your life.

Drop the “Lone Ranger” act

As a Lean servant leader, you must give up the notion that you’re the only one that has to have all the answers or solve all the problems. As the old saying goes, “There is no ‘I’ in ‘team’!” The next time you feel compelled to jump on that white horse of yours, stop and ask yourself, “Who should I ask to help me with this problem?” After all, even the Lone Ranger had help. Who are your “go-to” people that care about supporting and developing you as you move through life? Figure that out, and then pull them in, challenging them to find new and more creative ways to solve the problems you face together, as a team.

See the potential in everyone

Lean servant leaders are thoughtful enough to take the time to understand what motivates others. They don’t carelessly jump to conclusions about things, such as why someone is underperforming. Poor performance may not have anything to do with work but may instead be caused by something bleeding over from someone’s personal life. Next time you’re confronted with an employee performance issue, initiate a candid conversation around the issue at hand. Work with the person to find a solution that solves the problem so that once again they can contribute as a valuable member of the team. Lean servant leaders don’t give up on people; they see the potential we all have to achieve great things. They extend the effort to help us to overcome the obstacles on our way to success.

I once knew a woman who was a stellar employee. Over time, however, she began calling in sick a lot, and when she was at work, her mind seemed to be elsewhere. She eventually started spending more and more time away from work. I called her into my office to speak candidly with her about her recent downward performance trend, and in the course of the conversation, she disclosed to me that she was experiencing some serious personal issues. I had not expected that our conversation would take that kind of turn. I asked her what steps she was contemplating, and she said she very much wanted to address and resolve these issues, but she felt she did not have the support network to remove herself from this dysfunctional situation that was severely affecting both her personal and professional life. As we talked through her issues, I gave her the name and number of a friend of mine who could possibly help, leaving it up to her to take the first step.

A month later, her performance had drastically improved, and she told me she had reached out to the resource I had suggested and made some major changes in her life for the better. By simply asking her what was wrong and how I could help, she felt like someone cared, and it gave her the strength to make the necessary changes in her life and stick with the decision to move forward. Over the next six months, her performance continued to improve. Of course, not every employee will have such a drastic reason for performance issues (hopefully). But the takeaway here is that you never know what’s happening with someone until you ask.

Seek out and provide whatever is needed

Figure out what your team needs and then supply the right resources, whether that means adding skill sets or more people, removing impediments, or providing materials, tools, or realistic, constructive feedback to ensure they feel empowered and can be successful.

Get out of your office. Lean servant leaders don’t hide away from their people. They practice genchi genbutsu—the art of going and seeing for yourself what’s going on at the gemba (the place where the work is being performed). That doesn’t mean calling a meeting and herding everyone into a conference room. It means going to where your people are and spending time with them.

Look at problems as opportunities for improvement

Repeat after me: “Problems are good! Problems are good!” You must look at problems as opportunities to practice continuous improvement. Anyone that takes the attitude that there are no problems (also known as waste or muda in Lean) in their work area is kidding themselves. There is always room for improvement and making things better. Thinking that things are perfect ensures a culture of apathy in which problems fester and start to affect the quality of your work, causing people to become frustrated regarding their inability to effectively make positive change. Ignoring problems and thereby allowing them to grow and intensify is the fastest way to lose your best and brightest employees, because they will go in search of more honest and empathic companies and leaders who seek out their creativity and passion for improvement.

As a Lean servant leader, looking for and solving problems with your people should be the activity to which you devote most of your time and energy. Again, practice genchi genbutsu at the gemba, talk to your team, understand the problems they face, and work with them to solve those problems as a team. Then work to continuously improve on the solutions you put in place by challenging them to focus on the removal of muda (waste) at the gemba.

Develop an inquisitive mind in yourself and others

Many times, getting to the root cause of a problem requires digging. Accepting the first answer usually puts the focus on a symptom rather than the actual cause. You must challenge yourself and others to go beyond their normal thinking patterns by asking probing questions. Challenging people and exhibiting vulnerability in the problem-solving process is the way you grow both yourself and your people. Both the teacher and student end up learning something in the process.

Build a tolerance for failure

Your attitude toward mistakes and how you handle failure is also a determinant as to whether or not you are a true Lean servant leader. Mistakes must be looked at as just one more way we now know something doesn’t work. Mistakes aren’t life-ending events. Mistakes and failings offer valuable experiences that we can learn from and incorporate back into the process. If you’re not taking risks, you’re not learning and moving forward. Remember, the goal is to break the problem down into small, manageable chunks. And if you fail in one attempt to solve a problem, it doesn’t mean the end of the world as you know it. It just means you haven’t found the solution to the problem and must try again until a viable solution is found. For instance, did you know that Thomas Edison made one thousand unsuccessful attempts at inventing the light bulb? One thousand attempts! Failing was not part of his plan, and when a reporter asked him, “How did it feel to fail one thousand times?” Edison replied, “I didn’t fail one thousand times. The light bulb was an invention with one thousand steps.”7

Encourage independent thinking

Identify the gap or problem that needs to be solved and make sure your team has the resources to solve it, and then stand back and let them have at it. Just because they might not solve the problem the way you would doesn’t mean their solution is wrong. If they get stuck, be available to help. Ask them challenging questions about the direction they’ve taken to solve the problem, but encourage them to think independently.

During problem solving, encourage the importance of building consensus for the possible solution among all the stakeholders involved, before the solution is implemented. Building consensus uncovers additional ideas that might offer better solutions to the problem or identify possible unconsidered risks. Consensus ensures the people who must implement the solution thoroughly understand the effects it may have on their work. In this way, everyone feels like they’ve been given the opportunity to voice and address any concerns they might have about the most viable solution, validating that it’s the most optimal solution at the time.

Leave your ego and pride at the door

This one might be the hardest to accomplish, because successful leaders are generally full of self-confidence, willpower, and determination. However, as I’ve said before, being a Lean leader is not about you! It’s about helping those you serve to develop their self-confidence, willpower, and determination to succeed.

You must share, not hoard, your power to set your people up for success. You can’t intentionally let them fail so that you can ride in and save them. That type of behavior is self-serving and only boosts your ego. However, if what you are trying to build is an army of Lean servant leaders who lead by example, with respect, integrity, honesty, and dignity, and who live to serve and develop others, then you must leave your own ego and pride at the door. Instead, take pride in developing and supporting others as you and they both evolve to higher and higher levels of Lean servant leadership.

Respecting Others on the Road to Continuous Improvement

For those who aspire to practice Lean servant leadership, it all starts with the two pillars of The Toyota Way, which are (1) a profound respect for people and (2) a commitment to continuous improvement, known as kaizen.

Giving Context to Respecting Others

The easiest way to understand why respect is so important is to think about a time when you felt disrespected. Whether it was expressed through a person’s words or behavior, I bet the message came through loud and clear. How did that make you feel? How did you react? Probably with anger or disbelief for having been treated in this manner. It probably left you asking, “So what did I do to them to deserve this type of treatment?”

More times than not, the answer is “Nothing!” When people behave disrespectfully toward you, the underlying reason usually says more about them than it does about you. Disrespect often comes from an apathetic mind, which usually develops when people feel like no one cares for or respects them—so they treat others in this manner. Unfortunately, feeling that you’ve been disrespected enables disrespectful behavior, and you can either consciously or unconsciously return that disrespect to them, which can become a vicious circle in any relationship.

However, remember the old adage “You get what you give!” Being mindful and mature about your reactions and remaining respectful, acting with honor and humility, will get you much further than throwing attitude and returning the disrespect. When I run across someone like this, my first instinct is to be as respectful to them as I possibly can, because as a Lean leader you must model the behavior you’re looking for, as hard as that might be. When you treat people in the manner you want to be treated, it introduces a whole new dynamic to your interactions with them.

I’ve also found that smiling and being vulnerable helps as well. I smile and give an opening statement that asks for the person’s help; this goes a long way toward getting a conversation started off on the right foot. It takes the other person out of their head and current situation to focus on you and the situation at hand. Most people are more than willing to help others. As humans, we are inherently wired that way; it’s part of our nature to respond to vulnerability in a protective manner, instead of immediately putting up walls that cause miscommunication and mistrust. So the next time you are in a situation like this, give this technique a try. You might be amazed at the response you get.

Thinking with a Kaizen Mind

Contrary to popular Western beliefs and practices, kaizen is not an event or something you do occasionally. It’s a way of life and a philosophy that is practiced every day, at all levels, throughout the entire Lean enterprise. Its goal is the continuous improvement and optimization of not only the parts (such as individuals, teams, processes, services, and technology) but the entire system. It’s acutely focused on the removal of needless waste (muda) through the implementation of small, continuous improvements, aimed toward increasing productivity, quality, safety, and customer and employee satisfaction; improving delivery times; and lowering costs.

To develop a kaizen mind means you realize the importance of eliminating waste by committing to continuous, long-term improvement in the form of proactive, measured change. Yes, there is that word again: change! Kaizen is about spotting the necessary changes that need to be made to keep you, your followers, and the organization moving forward. Change is handled better when it’s acknowledged and dealt with in small, incremental steps, which is what kaizen is all about. Unfortunately, most change efforts fail due to the change being initiated and implemented as a massive, last-ditch effort to correct something that should have been addressed incrementally over time. If kaizen is happening, there’s no need for large-scale, disruptive change. Lean servant leaders realize that change is inevitable, and they don’t blindly ignore it. The need for continuous change must always live in the forefront of your conscious mind.

Kaizen is driven by a respect for people from both your customers’ and employees’ perspective, because it’s all about making the lives of those that buy or produce your products better and more rewarding. That means reducing the waste that’s all around you, from an emotional, mental, and physical perspective. When everyone in your organization is constantly seeking out waste and systematically removing it, then you’ve developed a kaizen culture in which continuous improvement becomes a way of life.

Acknowledging Your Responsibility to Develop Others

As a Lean servant leader, you have two main goals. First, you’re responsible for developing yourself and other potential leaders from both a job performance and a skill-set perspective, helping them to hone their leadership abilities. Second, you must continuously identify opportunities that enable yourself and others to stretch and grow by challenging the status quo and never accepting or becoming complacent in your quest for perfection. It’s just as important to vertically develop your skills and abilities within your area of expertise as it is to horizontally develop them across the organization, pushing yourself to be able to perform continuous improvement both within and outside of your comfort zone or area of expertise. In doing so, you put yourself in situations that remove you from the role of an expert, forcing you to learn to develop and draw upon your leadership skills, such as motivating people, inspiring by building your vision, influencing through consensus building, team development, listening, and coaching, to name a few. When you’re no longer the “expert,” you have no choice but to lead through your soft skills.

Also, a crucial responsibility of a Lean servant leader is to ensure that your “students” take responsibility for their self-development. However, as a leader, you remain accountable for their results. I know that sounds a little one-sided, but if you aspire to lead others, you must take full responsibility for developing your people as well. After all, you probably received assistance at some point in your career from someone who helped you to develop your abilities to lead. However, it’s unrealistic to think you will be able to devote major chunks of your time to everyone. So you must choose wisely and take the time to identify and then develop those individuals who show the most potential to effectively lead and work as a team. Here are some tips on how to accomplish that:

-

Closely observe those who follow you, making mental notes concerning who shows the potential for leadership versus those who don’t have any aspirations or interest in leading at all (which is okay as well). However, don’t make the mistake of thinking they don’t want to be developed. Different people have different career goals. Some may aspire to become an expert in their field, showing absolutely no interest in becoming a leader. You must recognize there are many ways to help someone develop, such as by freely sharing your expertise, which is good for both the individual and the company.

-

For your direct reports, set aside regular time to work on and discuss their development. You need to ensure they are on track and are getting what they need to continue their development. I suggest you also set aside four to six hours a month to mentor and coach those whom you don’t directly manage or lead. Allot time on a first-come, first-serve basis. I find mentoring and coaching others to be personally rewarding, and I’ve had many mentors, coaches, and teachers throughout my career, even though I wasn’t in a position to help them at that time. I am a firm believer in the “pay it forward” process of helping others.

-

Set clear expectations for those you lead so that both you and your students can measure progress and be accountable for their self-development. One of the things I do is to give my students a challenge they must complete before our next formal touchpoint. With my formal relationships, I expect the students to come prepared to discuss how they have attempted to solve the challenge given to them. With my informal relationships, I leave it up to the students to schedule the next meeting, after they’ve attempted to solve the challenge given to them. In this manner, I can easily ascertain who is willing to put the actual time and effort into their development so that we’re both using our time as wisely as possible. Also, using this technique puts the responsibility of self-development squarely on the shoulders of the students, who can take it as fast or slow as their schedule and time constraints permit.

-

Know that you’re going to be held accountable by your followers. This is a radical departure from the way many companies operate today. Ultimately, if a company is failing, who else should be held accountable for that end result other than the leadership team? However, more and more it seems that Western leaders have perfected the art of becoming “Teflon”—that is, not being accountable or taking responsibility for a lack of results. Everything just slides right off them. Followers must hold their leaders accountable, ensuring that Teflon leaders are not acceptable in a Lean culture. Leaders must share responsibility and accountability with their followers, as well as with other leaders, to ensure that the company continues to grow and evolve.

Learning to Serve While Developing Others

Becoming a Lean leader means being in a continuous loop that places you in the role of student, as well as teacher, over and over again throughout your career. And being a Lean servant leader requires developing a kaizen mindset so that you can help others in their development as well. This two-step process can be achieved with the help of the following Lean techniques:

- Toyota Business Practices (TBP)

- The most powerful tool for developing a kaizen mind is a problem-solving technique known as the Toyota Business Practices, or TBP. It’s based on the Plan/Do/Check/Act (PDCA) cycle, which has evolved over the years and was modified by the Japanese for their production purposes. Its focus is on helping you develop and hone your problem-solving capabilities through a systematic and repeatable continuous improvement process.

- On-the-job development (OJD)

- Once you’ve mastered TBP at the individual and team leader levels, you’re ready to move to the second step, which is assisting others in the development of their leadership skills, using another Lean technique known as on-the-job development, or OJD. OJD puts you in the role of sensei (coach or mentor) by working to develop potential leaders as they move through their TBP experiences. In this second step, your goal as sensei is to help others develop their abilities to both serve and lead.

However, before you move on to OJD, you need to understand another underlying tenet of the TBP, which is the PDCA cycle.

Kaizen and the PDCA Cycle

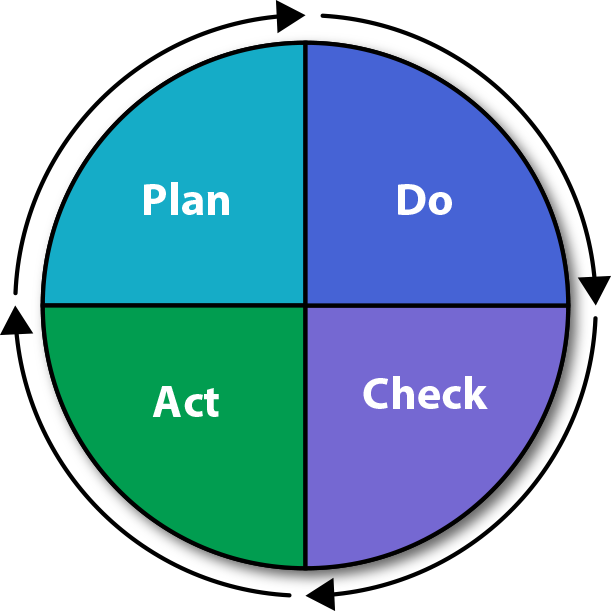

The PDCA cycle (shown in Figure 4-1) can be used to solve just about any problem or issue a leader, team, or company encounters. PDCA follows the scientific method8 that dates as far back as Galileo and is the standardized process scientists have used for centuries to uncover the best possible solution to a problem. The process itself is quite simple. First, you build the hypothesis, stating both the true and false or “null” states. Then you identify all the possible conclusions or outcomes. Next, you conduct experiments or studies to test the hypothesis, observing the results along the way. You continue to test over and over again, incorporating your learnings back into the hypothesis until it’s proven to be either true or false.

The PDCA cycle consists of the following four steps:

Step 1. Plan: Define a problem and hypothesize possible causes and solutions.

Step 2. Do: Implement the solutions.

Step 3. Check: Evaluate the results.

Step 4. Act: Return to step 1 if the results are unsatisfactory, or standardize the solution if the results are satisfactory.9

Figure 4-1. The PDCA circle

The Evolution of PDCA and TBP

In 1985, Dr. Kaoru Ishikawa, the father of the Total Quality Control (TQC) movement and author of the book What Is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way (Prentice Hall), extended the Japanese PDCA cycle to include additional planning steps, adding goals and targets and developing methods for reaching those goals in the Plan steps10 so that the organization can identify, solve, and standardize what has been learned. Dr. Ishikawa’s PDCA cycle consists of the following six steps:

Step 1. Plan: Determine goals and targets.

Step 2. Plan: Determine methods of reaching goals.

Step 3. Do: Engage in education and training.

Step 4. Do: Implement work.

Step 5. Check: Check the effects of implementation.

Step 6. Act: Take appropriate action.

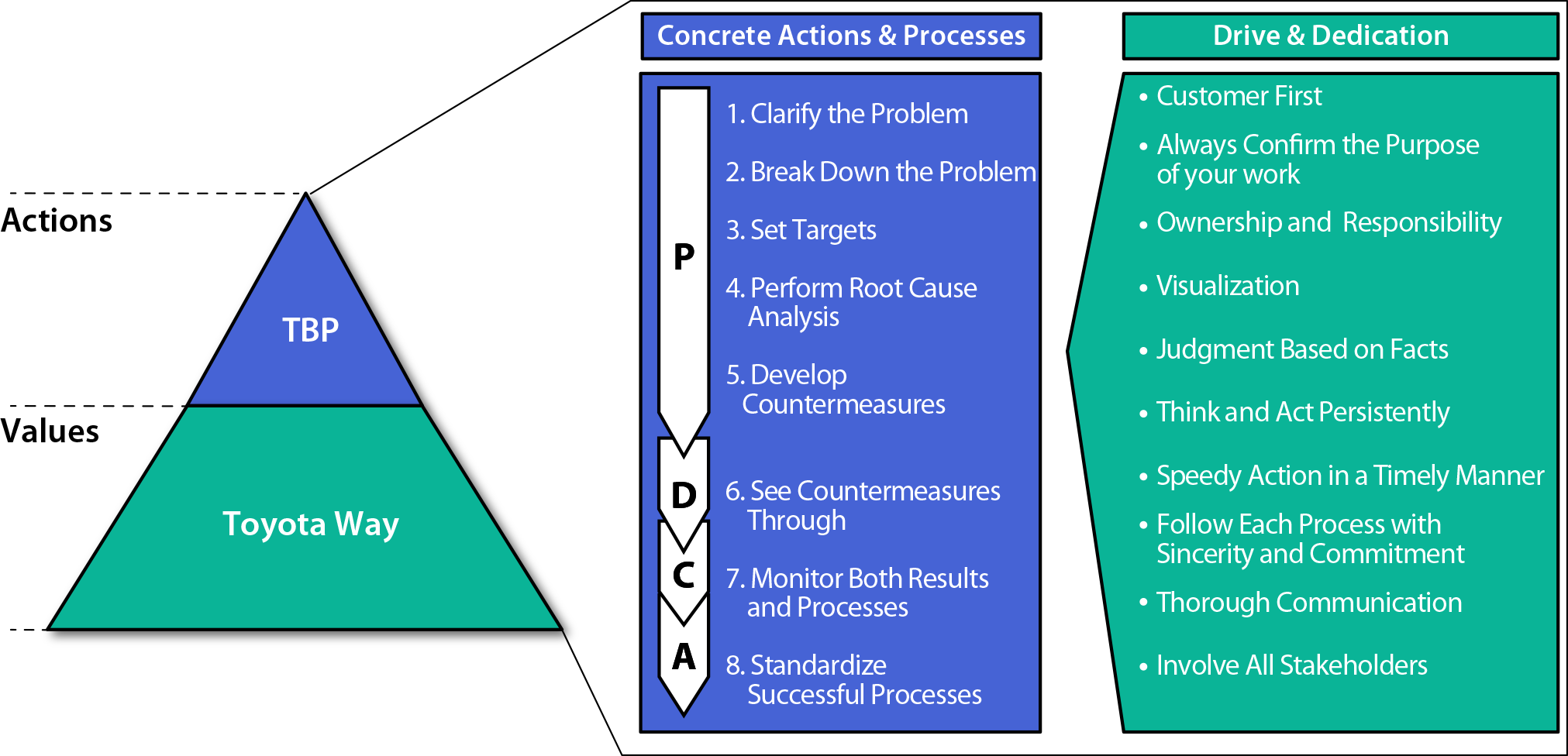

Toyota leaders then extended Ishikawa’s PDCA cycle to include two additional steps: in Step 1: Plan, they added “clarify the problem,” and in Step 2 they added “break down the problem,” to shift the emphasis to the customer, ensuring the problem is worth working on to gain consensus. They also deleted step 3 and added step 4: “perform root cause analysis,” ensuring the root cause of the problem being solved is well understood. This revised PDCA cycle became known as the Toyota Business Practices (TBP) method and has been implemented throughout Toyota as their overall problem-solving method. Figure 4-2 depicts the eight steps of the modern PDCA cycle, as implemented at Toyota, as well as the corresponding Toyota values that come alive through the implementation of the steps. For Toyota, TBP is not just a problem-solving method; it’s a way of bringing to life their values, expressed within the Toyota Way, through concerted and intentional effort.

Figure 4-2. Toyota Business Practices (TBP) and Toyota values (source: Toyota Motor Corporation)

Learning to Serve through TBP

You must first learn to serve your team through performing transformative kaizen projects and using the TBP problem-solving technique. Its focus is on the further development of both your leadership skills and your kaizen mind and Modern Lean capabilities. TBP is a consistent method that can be applied over and over again to develop leaders, both individually (by tackling a problem on your own) and in a team setting (where you either lead or follow under the watchful eye of your sensei or coach).

If you’re new to TBP and a coach cannot be found within your organization, consultants can act as coaches to teach you the techniques of TBP. However, in the long run, you and your team must own the solutions you create through TBP. It’s up to you to continuously improve the solution, which is how real and lasting change occurs and is sustained over time.

Keep in mind that your sensei is not there to supply answers. On the contrary, they are there to challenge and stretch you and/or the team. The sensei uses observation, questioning, and probing to ensure mastery of each step before you can move to the next one. TBP is also a means by which leaders can develop both vertically (within their areas of expertise) and horizontally (across the enterprise), because you don’t necessarily need to be an expert to contribute to the problem-solving process. For example, if you’re an expert in the field of human resources, you may well be able to contribute to a problem-solving effort in engineering with the kaizen team.

Now that you have an understanding of some of the core principles underlying the practice of leading and developing others through Lean servant leadership, let’s take a look at some of these principles in action.

Case Study: The Eight Steps of TBP in Action

The New Horizons car dealership in Portsmouth, North Carolina, was in trouble. The latest service ticket processing errors report from the customer service department of their automotive manufacturing supplier showed that the error ratio had hit an all-time high of 75%—5% higher than the previous month—and the company’s net promoter score had dropped to –20. To make matters worse, the owner, Jim Collins, had just received an email from the manufacturer stating that if New Horizons didn’t get the situation under control, they would take serious corrective measures.

Jim showed the report to his manager, Jannie. However, she was not an expert on running a service department this large. So Jim decided to call in Jannie’s long-time colleague, Nancy Peterson, whom Jannie had actually recommended to help them with the issues in the service department.

Upon arriving at the dealership the next day, Nancy immediately saw there was no one at the receptionist’s desk. Service agents and technicians were milling around, ignoring her—not a single person showed any indication of ending their conversation to help what very well could have been a customer waiting on the service department floor.

As she continued to stand there unassisted, as if she was invisible, she glanced through the service bay windows to see four men standing around the service bay desk. There wasn’t a single car in the bay, which struck her as odd because it was Monday morning, and the service departments she had managed in the past were usually packed with customers dropping off their cars. It was usually one of the busiest days of the week for a service department.

Nancy brought these concerns to Jim and Jannie when she finally sat down with them. Over the next couple of days, she spent a lot of time at the gemba within the service department. She observed the employees performing work in the service agent area, service bay, and garage. She listened to the receptionist take service request intake calls and watched the service agents’ interactions with customers, as well as with each other as they went about their daily duties. Nancy also dealt with a lot of irate customers both in person and over the phone. Most of them were upset over unauthorized service items that had mysteriously appeared on their service tickets, while others were upset about the work they had requested that wasn’t performed at all.

It quickly became clear to Nancy that she needed to discuss the whole service ticket issue with Jim. A lot of New Horizons’ issues were originating from how the service agents initiated service requests, and Nancy wanted to learn more about the dealership’s business practices. In a conversation with Jim, she asked him whether it was the policy of the dealership to add unauthorized repair and/or maintenance items to a service ticket, without informing the customer.

Jim was aghast and said of course that was not the policy—he was taken aback when Nancy reported that very thing was happening a lot. This type of behavior was not only unethical but also illegal. At that point, Jim and Nancy realized they needed to perform a complete overhaul of the Service Ticket Intake process. Nancy suggested using TBP to help get the department back on track; she proposed assembling a small kaizen team of staff members for three to four hours a day over the next couple of weeks to work with her to solve this problem. Since she had worked with Jannie before and knew she understood TBP, Nancy wanted her to lead the team.

Jim then confided to Nancy that the auto manufacturer had put him on probation; if he didn’t make some real headway on this problem over the next six months, they were going to revoke his dealership license. Nancy offered to have him join the team. However, Jim declined, admitting that he knew very little about the service department. Selling cars was his area of expertise and what he was very good at. He also wanted to avoid the appearance that the team was on a witch hunt with the staff, which Nancy understood and respected.

That night, before she left for the evening, Nancy sent out an email to Jannie, Rick, and Randy asking them to meet her in the break room tomorrow at 8:00 a.m. The first two were service agents, while Randy was a service technician. She explained in her email that they were going to embark on a problem-solving exercise around the service ticket error rate in an effort to identify and correct any problems they uncovered, and Jannie would act as team lead. She also added that their involvement was completely voluntary, and if they chose not to participate, there would be no repercussions.

Finally, she composed an email for Jim to send out to the entire staff, explaining the reason that Nancy and her team would be asking for their assistance over the next several weeks to figure out the root cause and begin to work on bringing the error rate down. Nancy viewed this as a very important step in the process. Communication is key to ensuring everyone understands what’s going on so that they can help with the problem-solving activities. Lean methods are based on the belief that the people closest to the work are best suited to solve the problems and improve upon the process. That means they must be the ones that identify and then solve the issue to ensure the actions taken are sustained and maintained over time.

The next morning, Nancy was at the dealership bright and early. She was excited to embark on this journey and to help Jim get the dealership’s problems solved. And, whether Jim realized it or not, they were all about to embark on a Lean journey that would set the dealership on a perpetual course of continuous improvement.

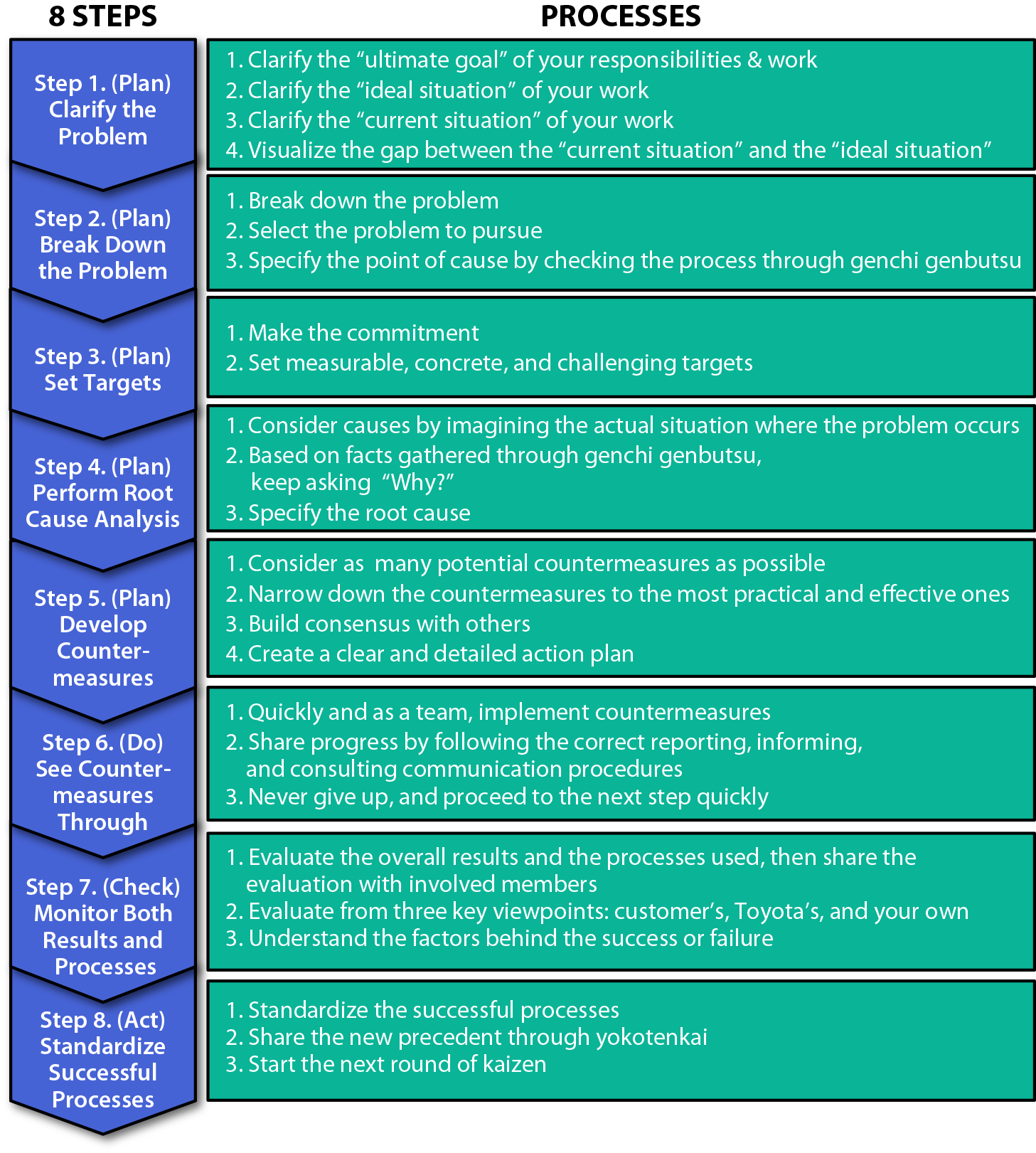

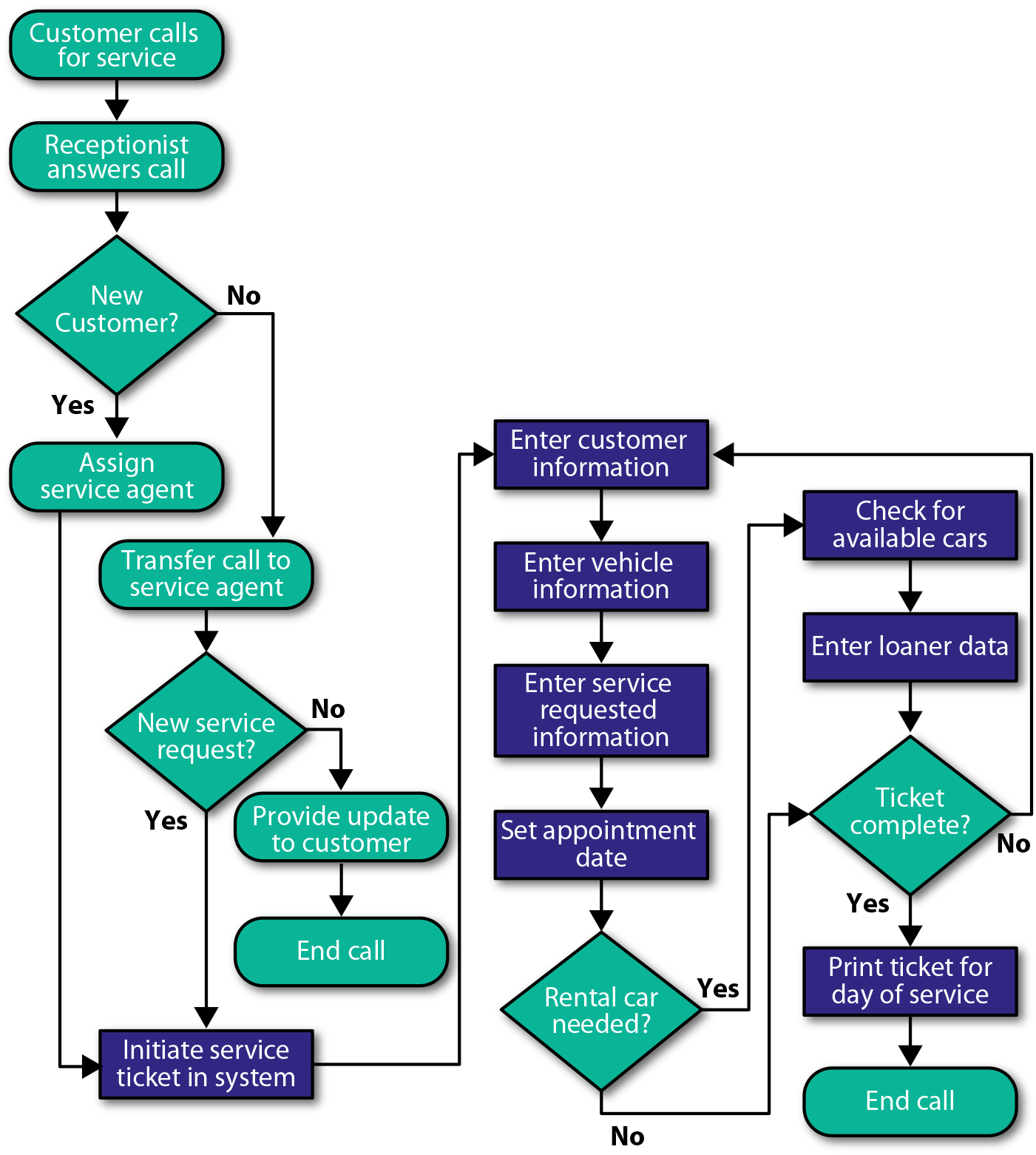

When she arrived in the break room, Rick, Randy, and Jannie were waiting for her, as well as a fourth person—Donna. Donna handled New Horizons’ loaner car program, and Jannie thought she’d be a great addition to the team. Nancy agreed, and they dug right into the discussion. Nancy started by providing an overview of the eight steps of the TBP problem-solving method, depicted in Figure 4-3. Her plan was to use a just-in-time method to give the team more in-depth coaching as they approached each step in the process. For now, a simple overview was enough.

Figure 4-3. The eight steps of the Toyota Business Practices problem-solving method (source: Toyota Motor Corporation)

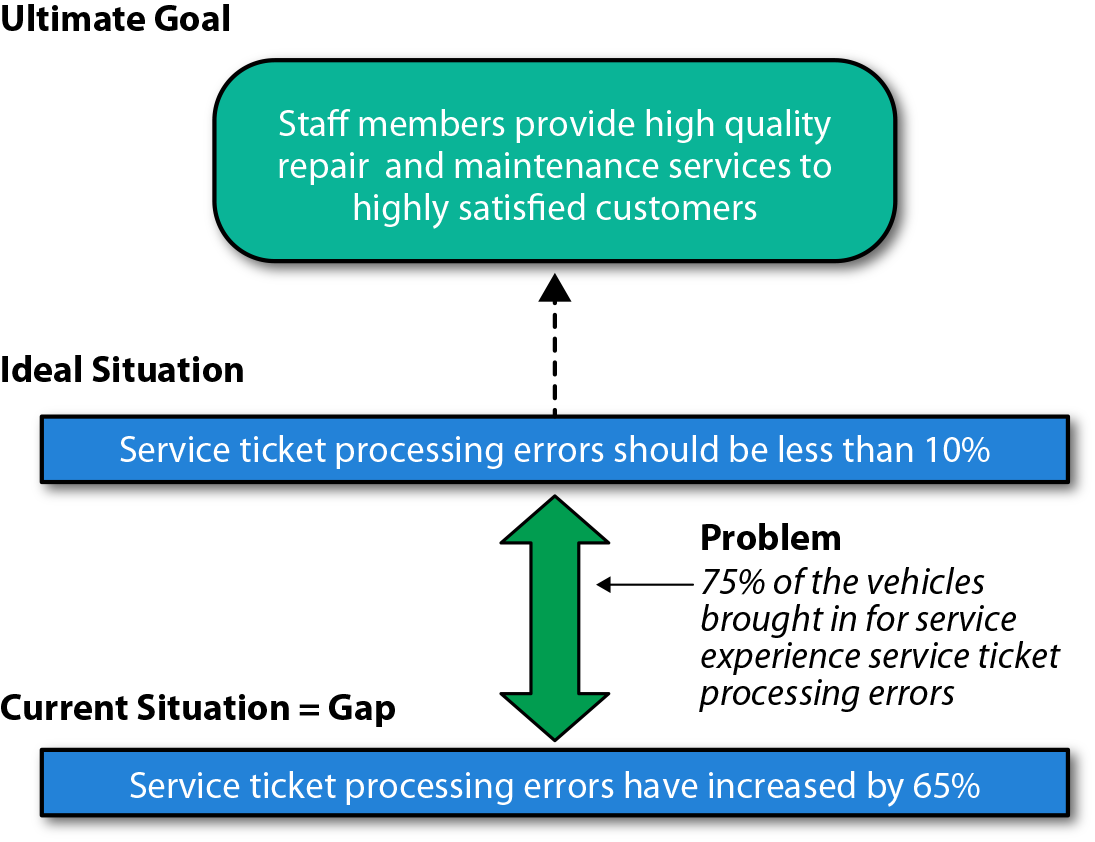

Step 1: Clarify the Problem (Plan)

Nancy explained that the team must start this process with the end state in mind by thinking about the “art of the possible.” As the team began to discuss the issues, they came to the realization that they were close enough to the work being performed to understand that there was a problem with how the department handled service tickets. Nancy referenced the 75% error processing rate, which represented a 65% increase over the last year. The auto manufacturer supplying the dealership with vehicles had set an acceptable error rate of 10%, and they tracked this statistic over time, because customer satisfaction was a priority. Nancy stressed that this error rate needed to become a metric the dealership tracked and paid attention to as well, because it was a measure of how the dealership provides value to its customers. “I don’t know if you’ve noticed,” she said, “but this dealership isn’t exactly brimming with business in the service department.”

“Wow, we suck,” Randy chimed in. “That’s awful!”

“Yes, that is why Jim has brought Nancy in,” Jannie added, “She’s dealt with other dealerships that have had similar problems. I know, because I’ve worked with her before and have seen this process work. I’m 120% behind this effort, because we need to get much better for our customers, the dealership, and of course for ourselves as well. This situation is really unacceptable!”

“Thanks Jannie, I appreciate your vote of confidence, and of course your support,” Nancy responded with a big smile. “So let’s get back to clarifying the problem.” Nancy kept the team on task and returned to clarifying the problem. She asked, “If you were to look out into the future, what would be the ideal state?” She reminded them that by starting with their ultimate goal and ideal situation, they could remove themselves from what was familiar and get away from preconceived notions concerning how they thought things ought to work. This is “the art of the possible”—envisioning the process functioning in an unencumbered, perfect future state. The gap between this state and the current reality was what the team needed to work on and solve for.

The team spent the next hour or so discussing the problem, the current and ideal situations, and the ultimate goal, identifying and diagramming them in Figure 4-4.

Figure 4-4. Step 1: Clarify the problem (Plan)

Step 2: Break Down the Problem (Plan)

After completing step 1, Nancy prepared the team for step 2, arguably the most difficult of the eight steps: breaking down the larger problem into multiple smaller, more specific problems that are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive so that they can be tackled individually in small steps.

Nancy asked the group to form two subteams for this step: Jannie with Randy and Rick with Donna. Each subteam picked a service agent to sit with for the rest of the morning to observe how the Service Request Intake process worked. They would discuss their observations the following day.

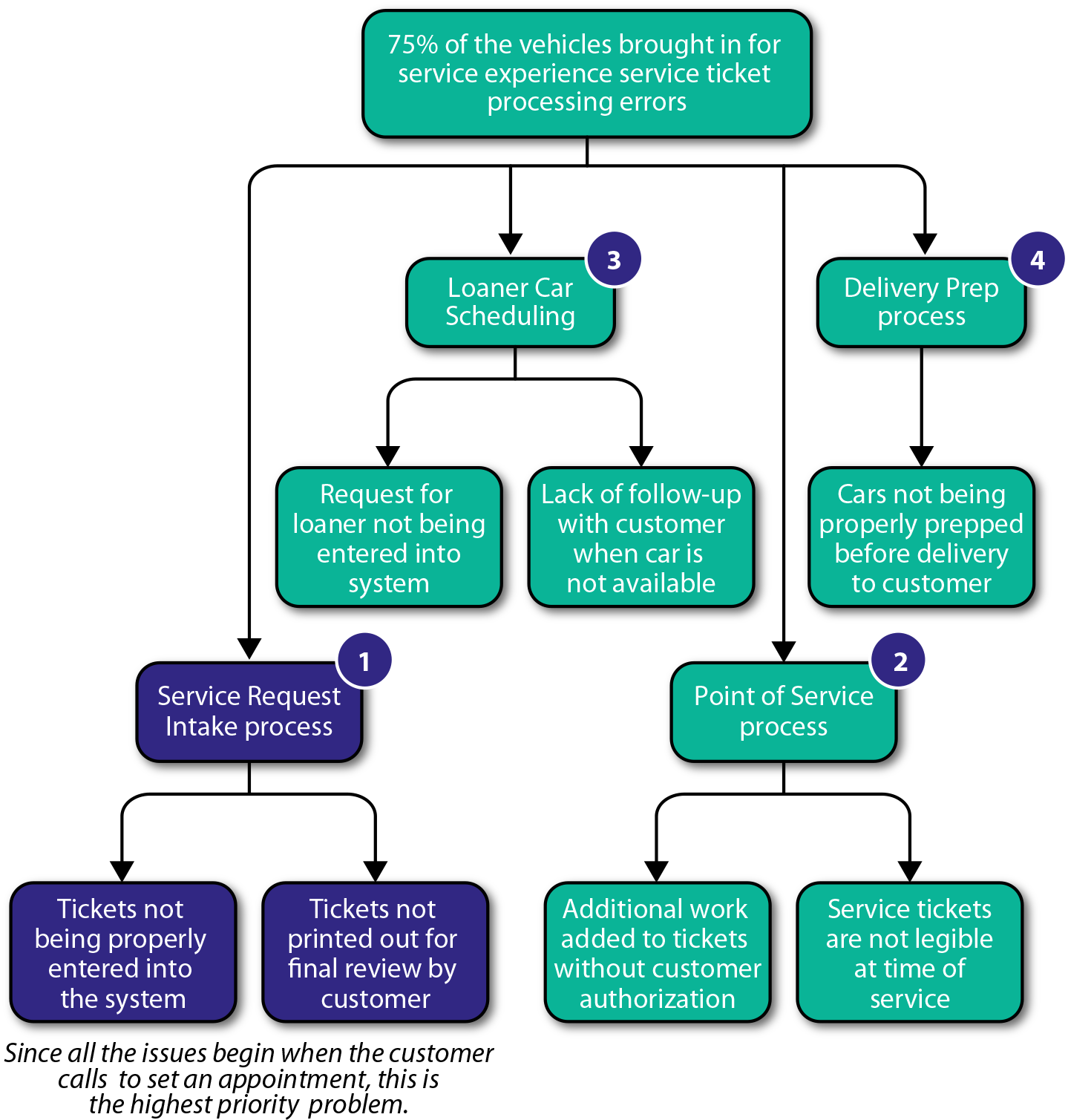

The next day, the team was eager to talk about what they’d learned—in fact, to Nancy’s surprise and delight, they reported they had stayed after work the previous night and worked on breaking down the problem. Jannie had even worked up a graphic (Figure 4-5) on a large whiteboard in the break room to illustrate the insights they had gained from spending time at the gemba.

Jannie reported that the team rotated through the agents every hour during the day, allowing them to gain insights from everyone. Breaking the main problem down, the team identified four subproblems; they then prioritized the subproblems, talking through each one’s level of urgency, importance, and potential for expansion, by asking the following questions:

-

Does it need to be solved now?

-

What would be the consequences of forgoing work on it?

-

What is its overall contribution to improving the situation?

-

What will happen if we continue to ignore it?

The team’s analysis verified that the Service Request Intake process was the biggest issue, since all the problems seemed to originate from there and were compounded downstream from that area. Randy noted he thought the Point of Service process was second, because a lot of tickets were not entered into the system, and half the time, the staff could not read the service agent’s handwriting. Getting service agents to come back to the garage to clarify a ticket was like pulling teeth. Donna noted that the loaner department experienced similar issues with scheduling. New Horizons needed better communication and coordination between the areas within the service department to ensure they were working as a team.

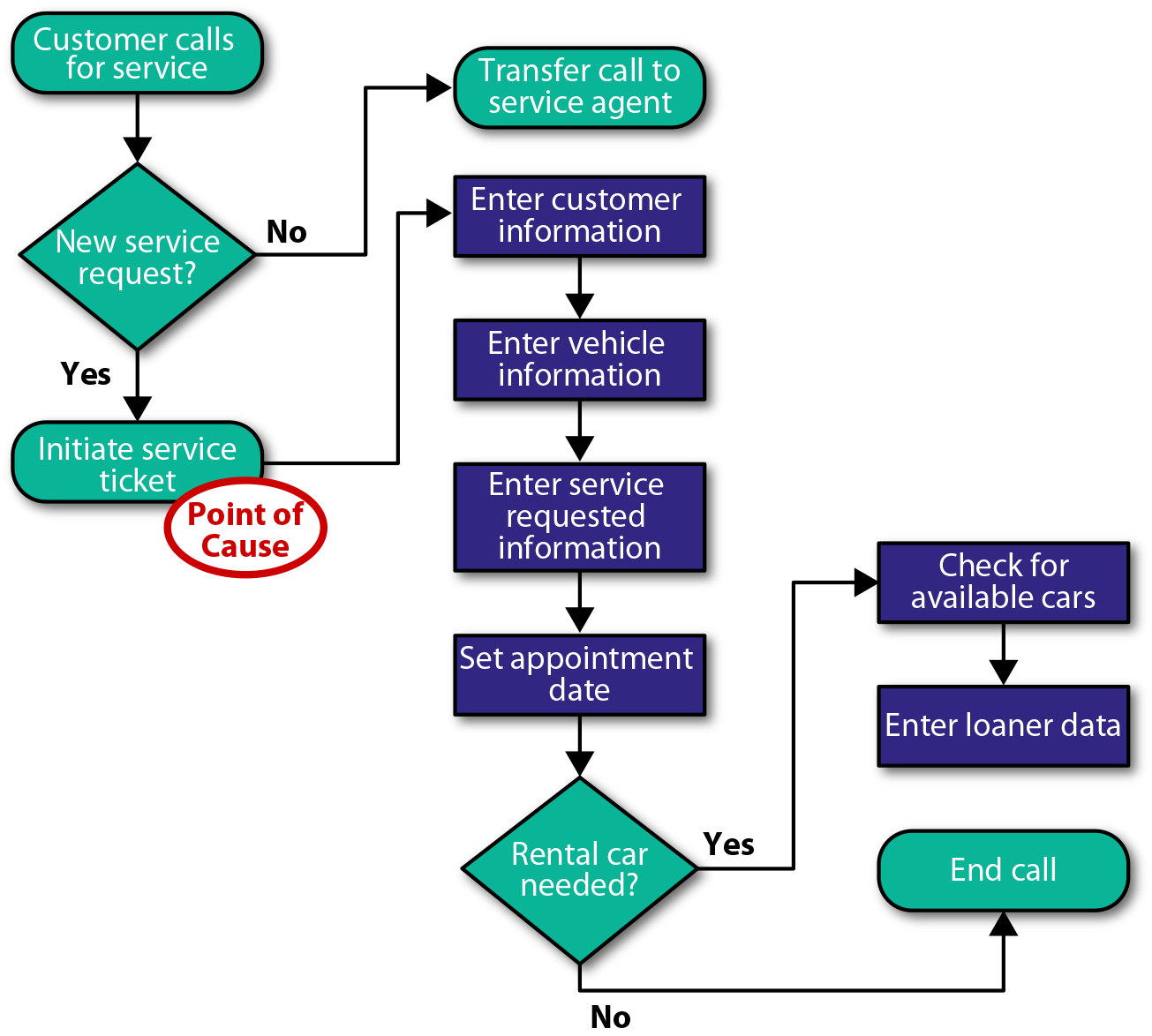

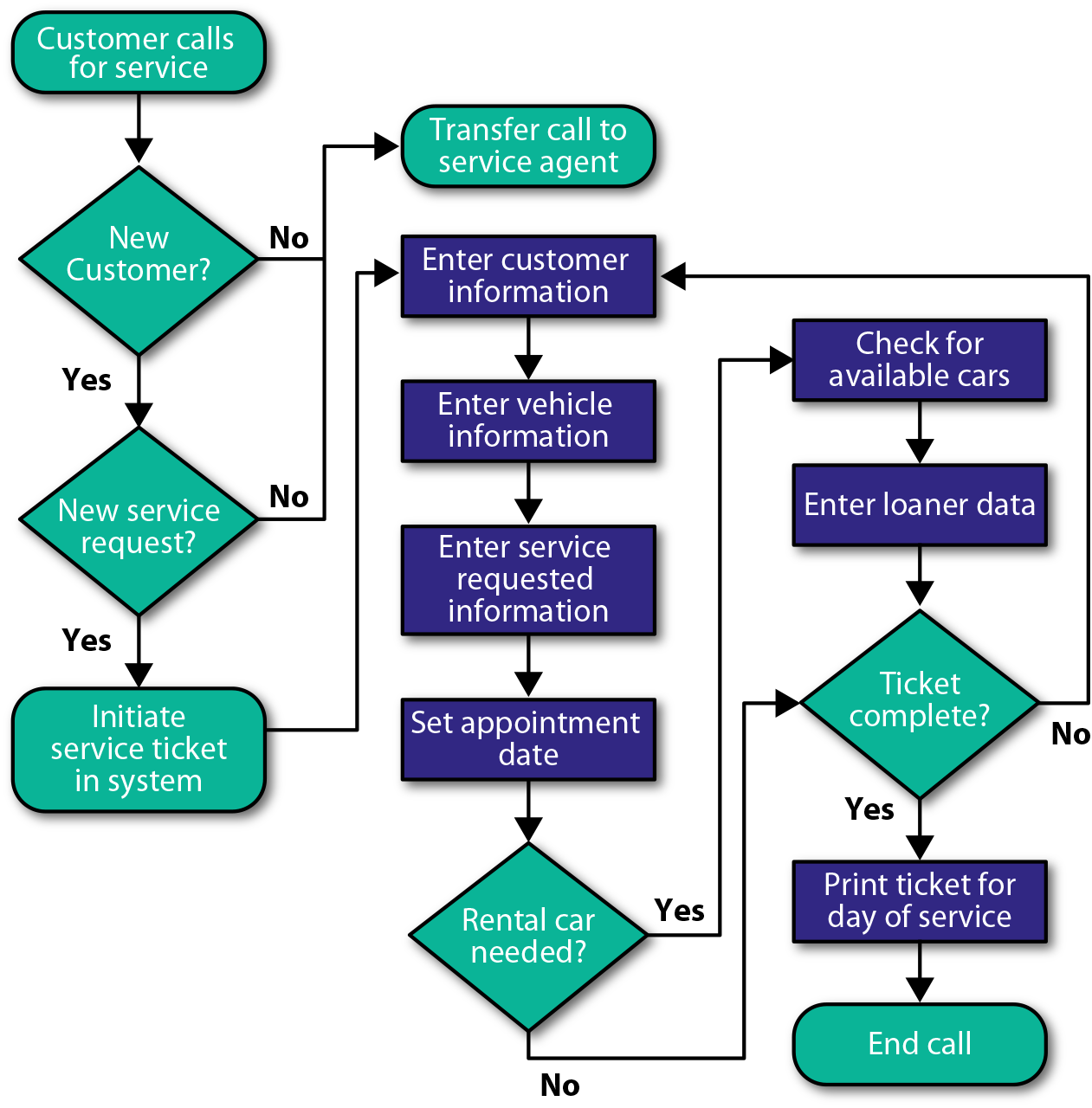

Figure 4-5. Step 2: Break down the problem (Plan)

Turning the whiteboard around to display another diagram, Jannie revealed the team had also documented the Service Request Intake process (Figure 4-6). The graphic showed a combined representation of what all of the service agents were currently doing. The team came to the consensus that the point of cause was when the ticket was initiated, which could either be using the service ticket system or by hand, since there was no standard set requirement. About 75% of the service agents preferred to skip using the system, because writing the tickets out by hand was faster and easier. A few had also said that because they were relatively new, they had not received any training on the system, and with the demands of their job, it was easier to write them out by hand than to enter them into the system.

The team also found that customer calls were randomly routed to the next available service agent. If agents were not on the phone, the automated system rang their desk phone until someone picked up. That might mean a customer could be rerouted up to seven times, and if no one picked up, the call then went to the receptionist or cashier. In other words, the team had found a lot of room for improvement in this process, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Figure 4-6. Current state for the Service Request Intake process at New Horizons

Nancy stood up and moved to the whiteboard. She restated what the team had told her, then said, “So if I’m hearing you correctly, if we were to isolate the point of cause, it would go something like this, right?” as she wrote the following:

Service request calls are randomly routed by the automated phone system to the first available person in the service department. That person then becomes responsible for entering and completing the service ticket (either within the service request intake system or by generating a handwritten ticket), as well as printing it for review and verification by the customer on the day of service, before any work is performed.

The team agreed that the whole process felt very random; there was no means of guaranteeing that the same agent would service the same customer from one visit to the next, which meant that customers were not getting consistent, personalized service. Considering that the dealership was selling high-end luxury brands, customers expected stellar service, but were receiving far less than they expected from the service department.

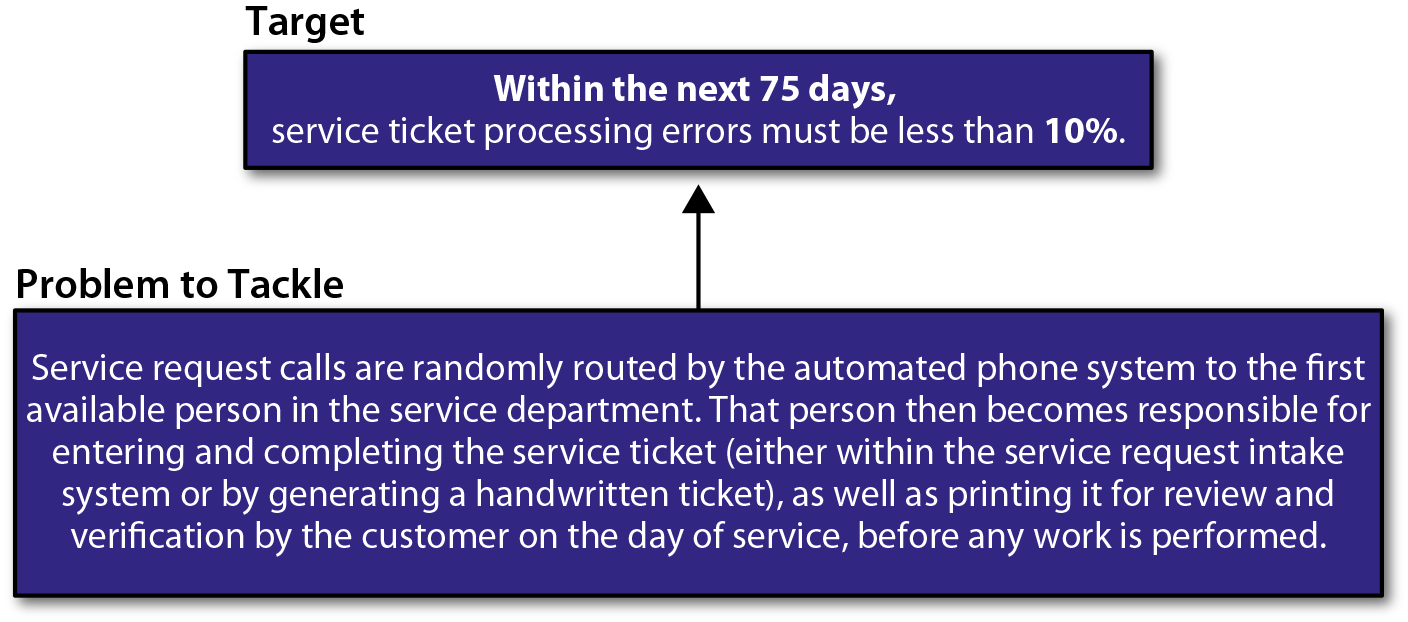

Step 3: Set Targets (Plan)

The team was now ready to move on to the next step: setting concrete, measurable, and challenging targets that could be objectively tracked over time. The challenge was to think about what their ideal outcome would be if they were to solve this problem, and then ratchet that up a notch or two. Nancy encouraged them to set aggressive targets because, after all, the team was on a quest for perfection. The question then became what the team could expect to accomplish from the most optimistic perspective possible. Or in simpler terms, what outcome was New Horizons trying to achieve, and by when?

Jim, the owner, had spoken with Nancy about getting to the root of the dealership’s problems and addressing them within 90 days. The team decided to push even harder than that and make the target 75 days. Having all agreed to go after this target, Jannie drew a box above the problem statement and wrote out the stated target (Figure 4-7).

Figure 4-7. Step 3: Set targets

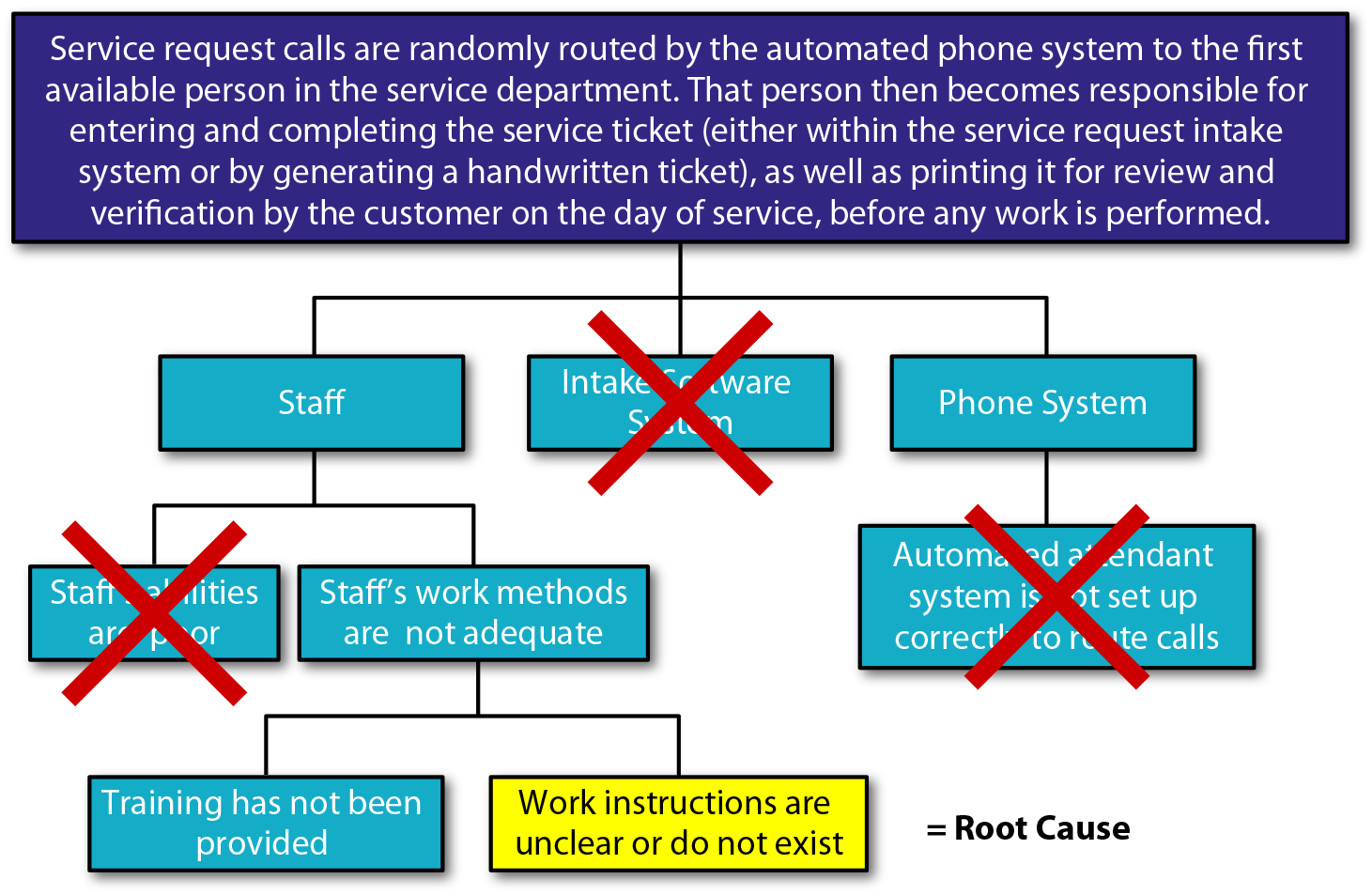

Step 4: Perform Root Cause Analysis (Plan)

The next step was for the team to determine the problem’s root cause. This was a crucial step, because if they ended up misidentifying the root cause, the team would risk solving for the wrong problem—or worse yet, solving for a symptom instead of the actual problem.

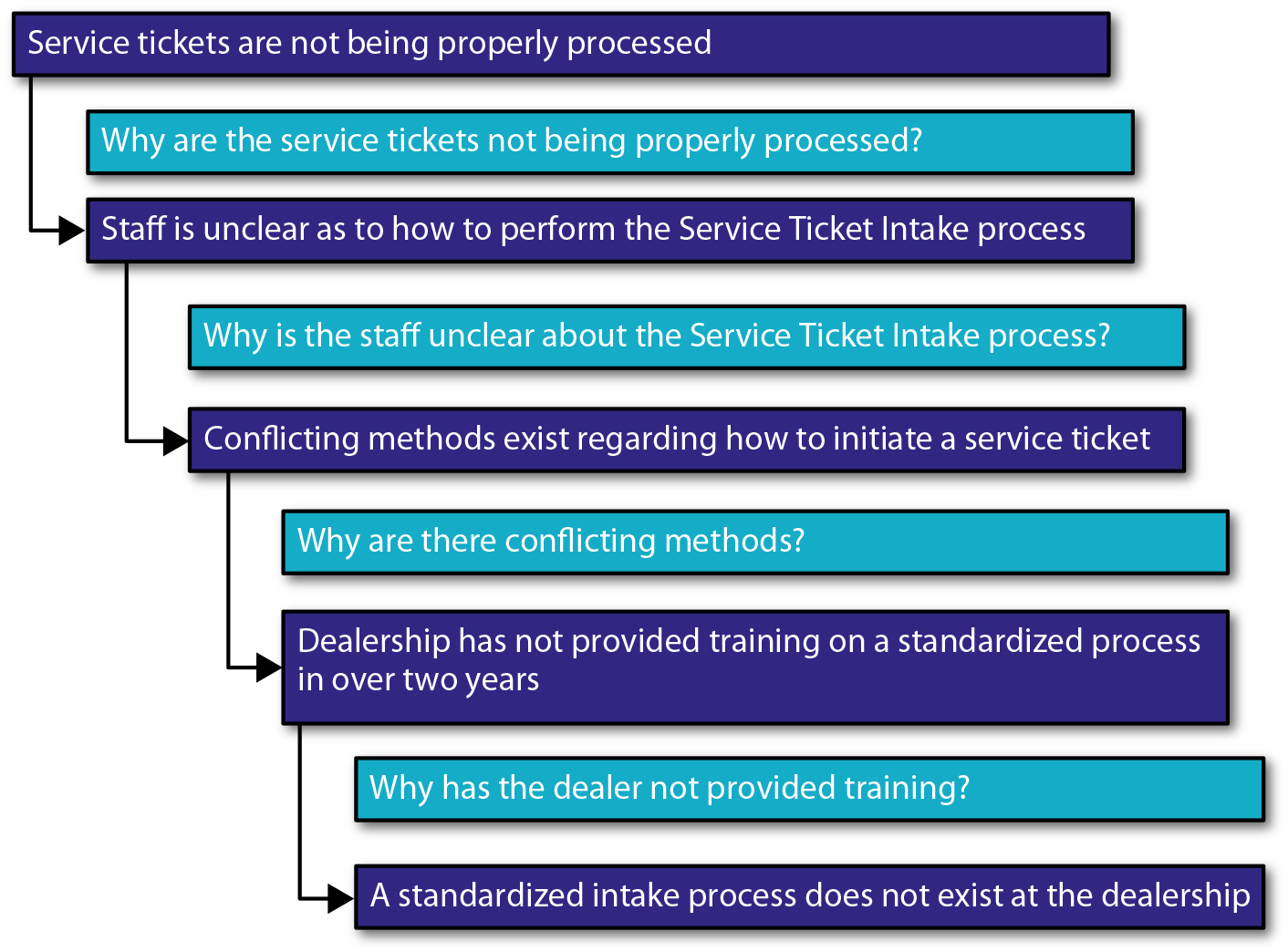

The team met in the break room again the next morning, and Nancy asked what conclusions they had reached about possible root causes. Rick took the lead and turned around the whiteboard, which revealed the assessments shown in Figure 4-8.

Figure 4-8. Step 4: Perform root cause analysis (Plan)

Donna explained how Jannie—who, you’ll remember, had worked with Nancy before—had shown the team how to do the 5 Whys technique so that they could develop a deeper understanding of the problem and identify the root cause. They had gone through each of the causes they’d identified and continued to ask why until they could precisely state a cause that was strictly supported by facts. The process allowed them to identify the actual cause and effect relationship. The 5 Whys for the root cause of “Work instructions are unclear or do not exist” are illustrated in Figure 4-9.

Figure 4-9. Results of the 5 Whys

Donna shared that by going to the gemba, they could verify that a direct cause and effect relationship indeed existed, ensuring they had the correct root cause—or at least the one that was highest priority. When they asked the service agents about whether they had been trained on a standardized process, most said that the most recent training had been done awhile back by the previous service manager, who was no longer at the company. However, that manager had not encouraged them to use the service request intake system, so most of them stopped using it either because it was slow and cumbersome or they hadn’t received training on it in the first place.

“OK, well then, I guess you all have this under control,” Nancy said with a smile as she started to get up from the table. The team looked somewhat startled, but then realized Nancy was kidding when she said, “All joking aside, this is great work!”

Step 5: Develop Countermeasures (Plan)

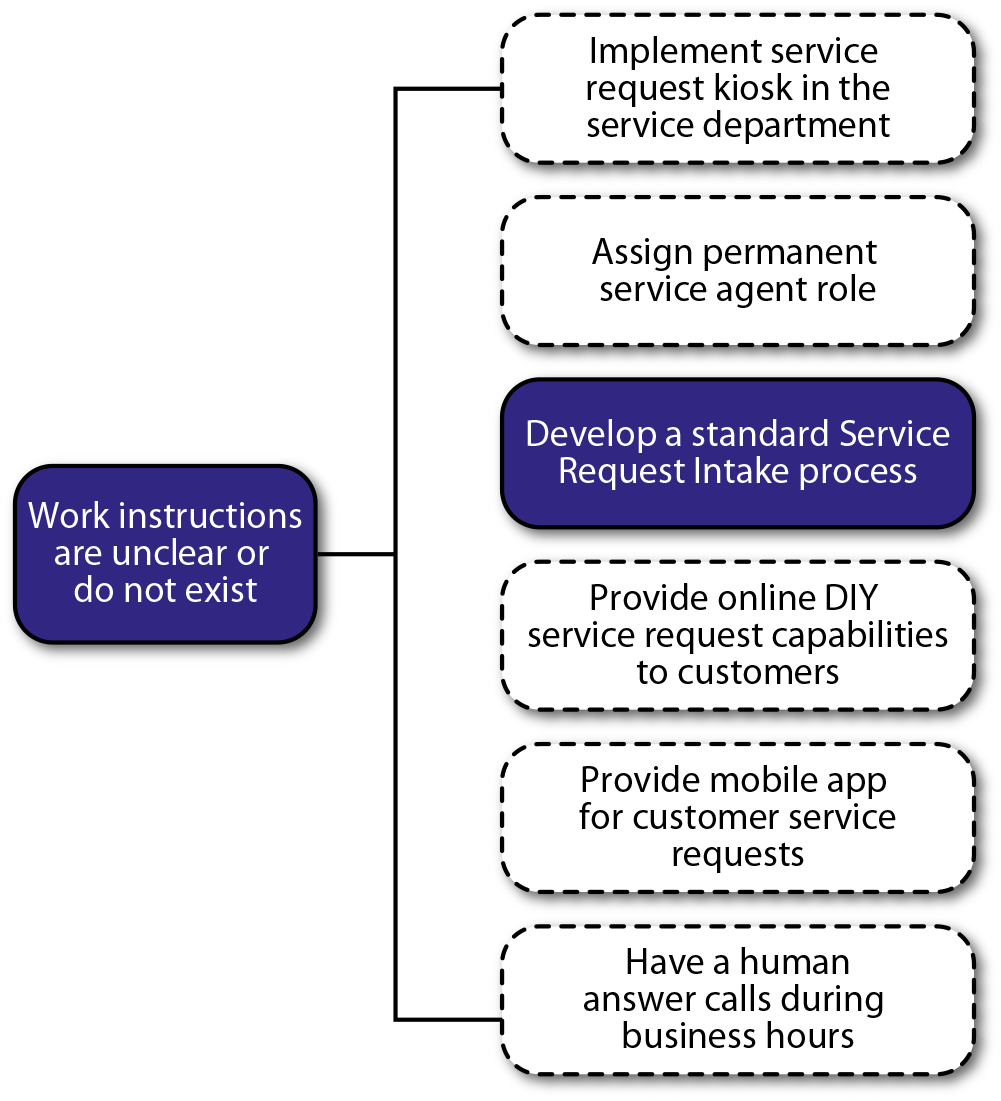

Now that the team had identified a root cause, they had to determine effective countermeasures using fact-based analysis and sound judgment, all while considering their customers, stakeholders, and the possible risks involved. Nancy reminded them that, as in step 1, the team was limited only by its creativity and imagination at this stage, because vetting the countermeasures would happen next, in step 6. Step 5 was only the planning stage.

Nancy called on Donna to lead a brainstorming exercise to come up with countermeasures. After about 15 minutes, the team generated the list depicted in Figure 4-10.

Figure 4-10. Step 5: Develop countermeasures

Nancy asked the team which of these countermeasures seemed most feasible. Some looked very doable, but which one would most effectively solve the root cause problem? She had them take a marker and put a star next to the one that each team member thought was most feasible.

The team unanimously chose “Develop a standard Service Request Intake process.” Nancy then proceeded to ask why.

Randy explained their reasoning: while some of the other countermeasures were doable and good ideas, they would take a long time—the mobile app and website form options, for example. The team had only 75 days—fewer than that, at this point—to make an impact. Likewise, assigning a permanent service agent and having a person always answer customers’ calls were also good ideas, but they were just symptoms of the root cause. The countermeasure with the “biggest bang for the buck”—both for the dealership and for its customers—was developing a standardized process.

Since the team was in agreement, the next step was to present this course of action to the stakeholders involved and discuss the risks and benefits before moving forward with the countermeasure. Nancy stressed that the team needed to ensure they built consensus on the plan of action, as the decision would impact everyone. She asked them to identify the stakeholders that would be affected if the countermeasure was implemented.

Jannie said that developing a standardized process would affect the whole service department, so the team needed to meet with the service agent, loaner car, and service technician teams to get their buy-in. Rick also noted that Jim would need to buy in as well.

“Sounds like a plan,” Nancy said. “I’ll take Jim and you all can meet with everyone else. Let’s take tomorrow to get these meetings done, and we’ll regroup on Friday morning.”

The next day, the team set up meetings with each of the groups and asked them to come to the break room, which by this point the team had dubbed the “war room.” They proceeded to walk each team through the five Planning steps of TBP they had performed so far. Everyone was allowed to voice their concerns or hesitations about this course of action. To the team’s surprise, there wasn’t a single person who raised an objection or concern; they received great comments and feedback they could incorporate back into the plan. They expanded their knowledge of the problem and gained deeper insight into how to solve it.

At the end of the day, Nancy caught up with the team in the war room and asked if they could stay a little while longer to walk Jim through the plan. They were a little surprised because the deal was that she would talk to Jim, but by now, the team knew Nancy well enough to know that there was a deliberate reason that always backed up her words and actions—so there must be a reason for this change in the plan. She walked down to Jim’s office and came back with him a few minutes later. They both sat down at the end of the table, and Nancy asked the team to walk him through the work they had performed to date.

Jannie kicked it off by walking Jim through the first graphic on the wall, which showed the eight steps of the Toyota Business Practices. Pointing to step 5, she mentioned that they were about to come out of the Plan phase and move to implementation of the Do phase, which meant building consensus for the plan before they started. “So we’ve met with each of the teams in the service department and walked them through everything you see on the walls around you. Now I’d like Donna to cover steps 1 and 2, Randy steps 3 and 4, and Rick will close us out with step 5.”

One by one they came up and covered the corresponding graphics hanging on the wall for each step. When Rick finished step 5, Jim stood up and started clapping. “Great job, team!” he said. “You have my full support to move forward!”

Step 6: See Countermeasures Through (Do)

Nancy reminded the team that the first five steps of TBP were very important to ensuring they were taking the right action: “Plan your work, then work your plan for success,” which applies when using TBP to solve major problems like the one the team was facing. The next step was to test for the most viable countermeasure—also known as a hypothesis—iteratively and incrementally, incorporating the feedback they gathered from each round of experimentation and pulling it back into the process to improve upon it.

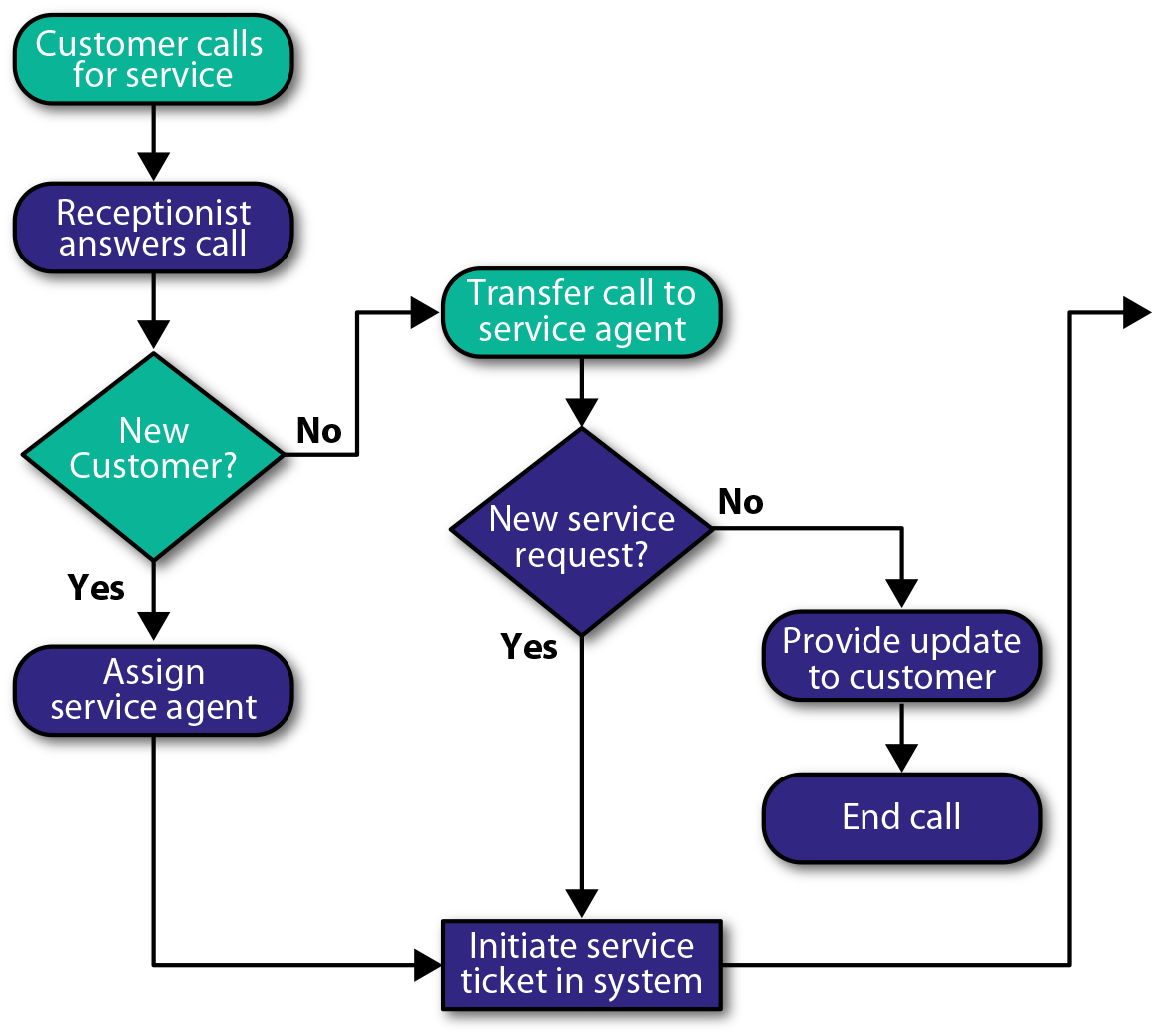

The first step was to develop the new standardized process flow, which the team had already discussed the day before. Jannie got up and spent a few minutes walking Nancy through their proposed process, as depicted in Figure 4-11. Nancy instinctively saw a few places where the process would probably need to be tweaked, but TBP is both a learning and development and a problem-solving method. So, she’d have the team implement the process the way it stood now to see what would happen, recognizing that challenges represent growth opportunities.

Figure 4-11. The Service Request Intake process

Nancy asked which service agents would be the guinea pigs to try out the new process; Jannie replied that Terry and Andrea were game. She and Randy would sit with Terry and Donna, and Rick would take Jan. They then agreed to regroup at 10:30 a.m. and check their progress.

The team headed out to the service agent area and spent about 30 minutes going over the process with Terry and Andrea to help them with the flow, until they got the hang of it. Then off they went to test the process.

Step 7: Monitor Both Results and the Process (Check)

The two teams spent the next couple of hours testing their countermeasure. However, it quickly became obvious that if this process was going to work, the call-routing process needed some changes. Terry and Andrea had been told not to alter their daily routines in any way, which meant they were away from their desks attending to customers or in the garage receiving status updates more than they were at their desks. The first three calls rolled over to the receptionist, because the service agents were either on the phone or away from their desks. When the receptionist answered a service request intake call, that tied her up as well. Frustrated, the team decided to call an emergency meeting to discuss the results they had observed.

Rick pointed out that, to make this countermeasure work, the team would have to make an immediate change in how the phone system worked. Customer calls were bouncing all over the place, and there was no rhyme or reason as to how they got answered. The team had identified this as a countermeasure but had prioritized it lower than the process itself, deeming it something of a “cart before the horse” thing. Rick added, “I think to realize the importance of the call routing issue, we needed to have a process in hand to test. I look at it as part of the feedback and learning cycle you talked to us about, Nancy.”

“That is a great attitude to take,” Nancy replied, “because if you had looked at it as a failure or missing the mark, you would have also missed the feedback and learning part. So good for you! And yes, I thought that might be the case. But like you said, who really knows until we test it out. So what are you proposing?”

Rick walked over to the process diagram and took out a marker. He inserted several new steps, adjusting the process so that the receptionist now answered all of the incoming calls. With this change, a customer’s call would be correctly routed and assigned to the appropriate service agent. The result is shown in Figure 4-12.

Figure 4-12. The revised Service Request Intake process

Rick noted that it would take tech support only about 15 minutes to turn off the auto-response system and that he would discuss the process change with Gail, the dealership’s receptionist, as well. He pointed out that they needed to remove her from the queue of folks that do intake, since answering calls and routing them would become a full-time job.

An hour later, Rick had everything switched over, and Gail began to answer all incoming calls in the service department. If it was an existing customer, she began to ask if they knew the name of their service agent. Surprisingly, most did or gave the name of the last service agent they had contact with at the dealership. As the calls began to funnel in, the teams were able to observe the service agents using the new process. Since Gail could enter this information into the service intake system, Nancy would now be able to monitor their workloads, ensuring customers were evenly distributed across the six service agents.

The next major hurdle the team encountered was the service request intake system itself. Since it was now mandatory to enter all service requests into the system and generate a service ticket, it quickly became painfully obvious that the majority of the service agents had no idea how to use the system. Upon observing them struggling with the system, Gail pulled Jannie aside and said, “I think I’m the one who knows that system the best, since I think I’m the only one using it. I could do a quick tutorial with Terry and Andrea to get them up to speed. If you could answer the phone, that would free me up to work with them. Just hold their calls for now.”

Jannie agreed, and Gail spent about 30 minutes walking Terry and Andrea through the system, with the team observing the process as well. “Jannie,” she said, “please route the next service call to Terry.”

The next call came in, and Jannie routed it to Terry. Gail sat next to him with the customer on the speakerphone, as Terry filled out the electronic form in the system. Terry was a little overwhelmed with the new process and system, but he handled it well and was able to get through the call. The team observed Terry, taking a lot of notes as he worked through the process.

The next call that came in went to Andrea. Having the benefit of both the training and observing Terry, she was able to pick up the pace a little and finished the call a couple of minutes sooner than he did. As she hung up, the team gave each other high fives for successfully getting through their first two calls.

Randy had timed Terry and Andrea on each step so that the team would have a benchmark to track the improvements. The total average time from start to finish was about 20 minutes for Terry and 19 for Andrea, giving an average of 19.5 minutes. The team decided it would be useful to track their times through the process and see what their average was consistently.

The team spent another hour with Terry and Andrea; then it was time to regroup with Nancy in the war room. When they arrived, she was already there with Jim. Sensing the team was a little surprised by his presence, she explained that she had invited Jim to listen to their feedback so that he could help make any decisions they might need as to next steps.

The team spent the next 15 minutes with Nancy and Jim, briefing them on the results from the experiments they performed with the Service Request Intake process. Jannie wrote their conclusions on the board:

-

The call-routing system is impersonal, and the routing algorithm does not fit the business outcome of personalized service from a luxury, high-end auto manufacturer.

-

The service agents lacked the training needed to enter tickets into the service request intake system.

-

The system was slow, and the agents spent a lot of time waiting on the screens to refresh between steps.

-

The average time through the process was 19.5 minutes. Over half that time was spent waiting on the system to refresh the screens.

-

The agents’ level of customer service was inconsistent. To ensure a consistent level of service, they might benefit from receiving customer service training.

Jannie reminded Jim and Nancy that the team had already implemented countermeasure #1 and received positive feedback from customers along the lines of “It’s nice to call in and talk to a human” and “Thank goodness I don’t have to be bounced around because of that awful automated system.”

Jim was impressed with the team’s progress, so they decided to regroup in the morning and discuss standardizing the process in step 8.

The team filed out of the war room, but Nancy hung back to speak with Jim. She confided that she had not wanted to put him on the spot in front of the team, but to get the results he was looking for, the team needed to tackle countermeasures #2 through #5 before standardizing and implementing this process. The intake system was painfully slow; the average customer was not going to want to spend at least 20 minutes on the phone to schedule a service appointment. She thought it was crucial that they make the necessary changes now: the hardware was old and out of date, and the service agents needed professional customer service training. The cost for the training and the changes would be $50,000, and the software and hardware could both be installed next week. Nancy also recommended a colleague, Lisa, who could conduct the training.

Jim thought that $50,000 sounded like a lot of money, but he also recognized that he really didn’t have much of a choice. He agreed it was time to invest in the company’s future.

Step 8: Standardize Successful Processes (Act)

The next week saw a lot of activity in the service department. IT worked with the software vendor to update the system, and Nancy worked with Jannie to replace all of the computers throughout the department with faster models that met the software vendor’s specifications. Additionally, all of the service agents received customer service training from Nancy’s colleague Lisa after work on Wednesday afternoon, and process and system training on late Thursday afternoon, which was traditionally a slow time for them. The final process that was implemented is depicted in Figure 4-13.

Figure 4-13. Final Service Request Intake process

On Friday morning, when the service department opened its doors, the service agents performed like a well-oiled machine. Calls were being routed, tickets were being entered into the system, and customers were leaving with smiles on their faces. That day, Nancy didn’t receive a single complaint, and things continued to improve over the next two weeks. The team continued to meet every day as they monitored progress and determined who needed a little extra help with the system or process to ensure things continued to run smoothly.

The next day, Jim got new numbers from the auto manufacturer on customer satisfaction and processing error rates. He was ecstatic: over the last month, New Horizons’ net promoter score had increased 25 points, and the error processing rate dropped 40 points. The manufacturer said it was the biggest single monthly drop they’d ever seen for any dealership since they began to keep those stats five years prior. That day, Nancy posted the report in the war room. She called the team together and informed them of the results. There were a lot of woot woots, high fives, and fist bumps among the team members.

“We’ve made great progress, team. You should all be very proud of what you’ve accomplished,” Nancy said. “So let’s get to work to figure out how we can drop the rate by an additional 25 points this month to hit our target of less than 10% within the next 30 days.”

At that point, Randy chimed in and said he had some ideas on how to make the handoff between the service agents and service technicians smoother, which might help lower the rate even more. Donna added that they still had issues in the loaner car program as well.

“OK, team,” Jannie said, “then let’s get to work!”

As well as Nancy’s team was performing, not everyone was on board: she had been observing her service agents throughout the eight steps of TBP, and everyone except for Angela had participated and helped to improve the process, as well as trying their best to adjust to the new system. However, Angela was still writing tickets out by hand, showing up late, and leaving early. It was clear to Nancy that Angela was not going to make the cut, so Nancy had to make the tough decision to let her go. Again, it wasn’t an easy decision, but it was necessary. A Lean enterprise needs buy-in across the board to work, and as a Lean leader, it is up to you to make these kinds of decisions for the greater good of the organization.

Using OJD to Develop Others

Hopefully, this case study has shown you how the TBP steps can play out when implemented. I also want to point out that since Jannie had been through several TBP initiatives and knew the process well, it might be time for her to assume the role of the OJD student at the end of this first iteration of the eight steps of the TBP process; it’s time for her to learn to coach and mentor other developing leaders, like Rick, Randy, and Donna. Nancy would be the most likely candidate to be Jannie’s OJD teacher. And hopefully you recognized the opportunities Nancy provided to her to develop her abilities to independently lead the team wherever possible, as the team moved through the eight steps of TBP.

An OJD student is expected to coach and mentor a developing leader who either is leading a TBP team or is an individual contributor. Through this process, the student becomes the master and the master becomes the student, as they are also mentored and coached by their teacher.

In this manner, the developing leader is likened to being an apprentice who learns their craft under the wise guidance and watchful eye of a master craftsperson. Learning is accomplished by doing, not by merely sitting in a classroom and being lectured to. There is a time and place for that, and classroom education is important, but at some point you must learn by actually “doing”—by being mentored and coached by a master teacher through your process of trial and error, allowing you to learn and grow along the way through feedback, which is the most direct way to master your craft.

However, keep in mind that before you can begin OJD, you must first master TBP; it’s a prerequisite. By first practicing and honing your TBP skills, you not only learn TBP but also how to lead kaizen or continuous improvement teams, developing both yourself and team members along the way. The final assignment for OJD students is to act as the teacher within their workplace, to mentor and coach a potential leader through leading a TBP improvement effort. Using the four steps of OJD, it’s now your turn to act as the sensei, both receiving and giving feedback and coaching from your teacher, as well as giving it to the leader you are developing. Let’s take a closer look at the four steps involved in OJD, which again follow the PDCA cycle.

Step 1: Pick a Problem with Your Team (Plan)

Based on the strategic goals of the organization, the TBP team leader and OJD student (or aspiring coach) must pick a problem that ties into the company’s overall goals and also challenges and stretches the skills and abilities of both the leader and the coach. Going back to our case study, Randy had mentioned that he had some ideas on how to make the handoff between the service agents and service technicians smoother, which might help lower their processing error rate even more. In this situation, Nancy would act as Jannie’s OJD coach and Jannie would be the OJD student, while Randy would be the potential TBP leader in training.

Step 2: Appropriately Divide the Work Among Accountable Team Members, Making the Direction Compelling (Plan)

The TBP team leader (Randy) being coached by the OJD student (Jannie) must understand the crucial tasks and targets required to accomplish the improvement effort. Then, both must convey the purpose of each objective to the team members, allowing them to determine how to perform the work in both a meaningful and achievable way, challenging and stretching their skills and abilities. As the OJD teacher, Nancy observes Jannie and provides feedback on her performance, helping her to grow and challenging her to make sure the team grows and learns as well.

Step 3: Execute within Broad Boundaries, Monitor, and Coach (Do and Check)

This is the phase in which the leader (Randy) and team execute the steps within TBP. The leader must constantly observe how team members carry out the work, understanding what issues they’re dealing with and what is and isn’t going well from a people and process perspective. Jannie, as the OJD student, coaches Randy in understanding and identifying corrective steps to improve both individual and team performance to ensure a successful outcome. Nancy again, as the OJD teacher, observes Jannie and provides feedback on her performance while interacting with Randy’s team.

Step 4: Feedback, Recognition, and Reflection (Act)

If the TBP leader (Randy) or team ventures near or just beyond the established guardrails or boundaries set for the effort, Jannie, the OJD student, has the opportunity to perform a course correction by using a teaching moment to get them back on the right track. This practice allows Jannie to observe how a leader or team experiences failure, digests it, and understands it to move on as quickly as possible to continue the search for what does work. Also, both Randy as the leader and Jannie as the OJD student must ensure they are both providing adequate feedback when evaluating team and individual performance, supplying recognition when the goal is achieved. They both must ensure they are having honest and direct dialogues regarding individual performance.

The final evaluation is a 360-degree one based on both the OJD student’s (Jannie’s) reflection of their own performance and feedback from the person (Randy) that was coached and mentored and from the teacher (Nancy) or sensei. A simple grade of pass or fail is given. If you’re the OJD student, receiving a passing evaluation means you’re now able to lead TBP teams and act as an OJD coach. A failing evaluation means you will need to go back and begin again with another potential leader. In either case, the feedback received is fed back into your development plan, as you continue to work with your sensei to further develop and hone your leadership abilities.

Conclusion