In this chapter and the previous chapter, we’ve worked with many different user interface objects and made a lot of new classes that are sort of like components. Our new classes do one particular thing well; a number of them can be added to applets or other containers just like the standard Swing components; and several of them are lightweight components that use system resources efficiently because they don’t rely on a peer. But we haven’t created new components; we’ve just used Swing’s impressive repertoire of components as building blocks. In this section, we’ll create an entirely new component, a dial.

Up until now, our new classes still haven’t really been

components. If you think about it, all our classes have been fairly

self-contained; they know everything about what to do and don’t

rely on other parts of the program to do much processing. Therefore,

they are overly specialized. Our menu example created a

DinnerFrame class that had a menu of dinner

options, but it included all the processing needed to handle the

user’s selections. If we wanted to process the selections

differently, we’d have to modify the class. A true component

separates the detection of user choices from the processing of those

choices. It lets the user take some action and then calls another

part of the program to process the action.

So we need a way for our new classes to communicate with other parts of the program. Since we want our new classes to be components, they should communicate the way components communicate: by generating event objects and sending those events to listeners. So far, we’ve written a lot of code that listened for events but haven’t seen any examples that generated its own custom events.

Generating events sounds like it ought to be difficult, but it

isn’t. You can either create new kinds of events by subclassing

java.util.EventObject, or use one of the standard

event types. In either case, you need to register listeners for your

events and provide a means to deliver events to your listeners.

Swing’s JComponent class provides a

protected member variable, listenerList, that you

can use to keep track of event listeners. It’s an instance of

EventListenerList; basically it acts like the

maître d’ at a restaurant, keeping track of all event

listeners, sorted by type.

Often, you won’t event need to worry about creating a custom

event type. JComponent has methods that support

firing off

PropertyChangeEvent

s whenever one of the component’s

properties changes. The example we’ll look at next uses this

infrastructure to fire PropertyChangeEvents

whenever a value changes.

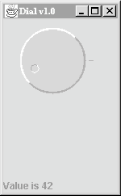

The standard Swing classes don’t

have a component that’s similar to an old fashioned

dial—for example, the volume control on your radio. In this

section, we implement a Dial class. The dial has a

value that can be adjusted by clicking and dragging to

“twist” the dial. As the value of the dial changes,

DialEvents are fired off by the component. The

dial can be used just like any other Java component. We even have a

custom DialListener

interface that matches the

DialEvent class. Figure 15.11

shows what the dial looks like; it is followed by the

Dial code.

//file: Dial.java

import java.awt.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

import java.beans.*;

import java.util.*;

import javax.swing.*;

public class Dial extends JComponent {

int minValue, value, maxValue, radius;

public Dial( ) { this(0, 100, 0); }

public Dial(int minValue, int maxValue, int value) {

this.minValue = minValue;

this.maxValue = maxValue;

this.value = value;

setForeground(Color.lightGray);

addMouseListener(new MouseAdapter( ) {

public void mousePressed(MouseEvent e) { spin(e); }

});

addMouseMotionListener(new MouseMotionAdapter( ) {

public void mouseDragged(MouseEvent e) { spin(e); }

});

}

protected void spin(MouseEvent e) {

int y = e.getY( );

int x = e.getX( );

double th = Math.atan((1.0 * y - radius) / (x - radius));

int value=((int)(th / (2 * Math.PI) * (maxValue - minValue)));

if (x < radius)

setValue(value + maxValue / 2);

else if (y < radius)

setValue(value + maxValue);

else

setValue(value);

}

public void paintComponent(Graphics g) {

Graphics2D g2 = (Graphics2D)g;

int tick = 10;

radius = getSize( ).width / 2 - tick;

g2.setPaint(getForeground().darker( ));

g2.drawLine(radius * 2 + tick / 2, radius,

radius * 2 + tick, radius);

g2.setStroke(new BasicStroke(2));

draw3DCircle(g2, 0, 0, radius, true);

int knobRadius = radius / 7;

double th = value * (2 * Math.PI) / (maxValue - minValue);

int x = (int)(Math.cos(th) * (radius - knobRadius * 3)),

y = (int)(Math.sin(th) * (radius - knobRadius * 3));

g2.setStroke(new BasicStroke(1));

draw3DCircle(g2, x + radius - knobRadius,

y + radius - knobRadius, knobRadius, false );

}

private void draw3DCircle( Graphics g, int x, int y,

int radius, boolean raised) {

Color foreground = getForeground( );

Color light = foreground.brighter( );

Color dark = foreground.darker( );

g.setColor(foreground);

g.fillOval(x, y, radius * 2, radius * 2);

g.setColor(raised ? light : dark);

g.drawArc(x, y, radius * 2, radius * 2, 45, 180);

g.setColor(raised ? dark : light);

g.drawArc(x, y, radius * 2, radius * 2, 225, 180);

}

public Dimension getPreferredSize( ) {

return new Dimension(100, 100);

}

public void setValue(int value) {

firePropertyChange( "value", this.value, value );

this.value = value;

repaint( );

fireEvent( );

}

public int getValue( ) { return value; }

public void setMinimum(int minValue) { this.minValue = minValue; }

public int getMinimum( ) { return minValue; }

public void setMaximum(int maxValue) { this.maxValue = maxValue; }

public int getMaximum( ) { return maxValue; }

public void addDialListener(DialListener listener) {

listenerList.add( DialListener.class, listener );

}

public void removeDialListener(DialListener listener) {

listenerList.remove( DialListener.class, listener );

}

void fireEvent( ) {

Object[] listeners = listenerList.getListenerList( );

for ( int i = 0; i < listeners.length; i += 2 )

if ( listeners[i] == DialListener.class )

((DialListener)listeners[i + 1]).dialAdjusted(

new DialEvent(this, value) );

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

JFrame f = new JFrame("Dial v1.0");

f.addWindowListener( new WindowAdapter( ) {

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent e) { System.exit(0); }

});

f.setSize(150, 150);

final JLabel statusLabel = new JLabel("Welcome to Dial v1.0");

final Dial dial = new Dial( );

JPanel dialPanel = new JPanel( );

dialPanel.add(dial);

f.getContentPane( ).add(dialPanel, BorderLayout.CENTER);

f.getContentPane( ).add(statusLabel, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

dial.addDialListener(new DialListener( ) {

public void dialAdjusted(DialEvent e) {

statusLabel.setText("Value is " + e.getValue( ));

}

});

f.setVisible( true );

}

}Here’s

DialEvent

, a simple subclass of

java.util.EventObject:

//file: DialEvent.java

import java.awt.*;

public class DialEvent extends java.util.EventObject {

int value;

DialEvent( Dial source, int value ) {

super( source );

this.value = value;

}

public int getValue( ) {

return value;

}

}Finally, here’s the code for

DialListener

:

//file: DialListener.java

public interface DialListener extends java.util.EventListener {

void dialAdjusted( DialEvent e );

}Let’s start from the top of the Dial class.

We’ll focus on the structure and leave you to figure out the

trigonometry on your own.

Dial’s main( )

method demonstrates how to use the dial

to build a user interface. It creates a Dial and

adds it to a JFrame. Then main( ) registers a dial listener on the dial. Whenever a

DialEvent is received, the value of the dial is

examined and displayed in a JLabel at the bottom

of the frame window.

The constructor for the Dial class stores

the dial’s minimum, maximum, and current values; a default

constructor provides a minimum of 0, a maximum of 100, and a current

value of 0. The constructor sets the foreground color of the dial and

registers listeners for mouse events. If the mouse is pressed or

dragged, Dial’s spin( ) method is called to update the dial’s value. spin( ) performs some basic trigonometry to figure out what the

new value of the dial should be.

paintComponent( )

and draw3DCircle( )do a lot of trigonometry to figure out how to display the

dial. draw3DCircle( ) is a private helper method

that draws a circle that appears either raised or depressed; we use

this to make the dial look three-dimensional.

The next group of methods provides ways to retrieve or change the

dial’s current setting and the minimum and maximum values. The

important thing to notice here is the pattern of

"getter” and “setter”

methods for all of the important values used by the

Dial. We will talk more about this in Chapter 19. Also, notice that the setValue( )

method does two important things: it

repaints the component to reflect the new value and fires an event

signifying the change.

If you examine setValue( ) closely, you’ll

notice that Dial actually fires off two events

when its value changes. The first of these is a

PropertyChangeEvent, a standard event type in the

Java Beans architecture. The second event is our custom

DialEvent type.

The final group of methods in the Dial class

provide the plumbing that is necessary for event firing.

addDialListener( ) and

removeDialListener( ) take care of maintaining the

listener list. Using the listenerList member

variable we inherited from JComponent makes this

an easy task. The fireEvent( )

method retrieves the registered

listeners for this component. It sends a DialEvent

to any registered DialListeners.

The

Dial example is

overly simplified. All Swing components, as we’ve discussed,

keep their data model and view separate. In the

Dial component, we’ve combined these

elements in a single class, which limits its reusability. To have

Dial implement the MVC paradigm, we would have

developed a dial data model and something called a UI-delegate that

handled displaying the component and responding to user events. For

a full

treatment of this subject, see the

JogShuttle example in Java

Swing, by Robert Eckstein, Marc Loy, and Dave Wood

(O’Reilly & Associates).

Get Learning Java now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.