Chapter 4. Expressions and Control Flow in PHP

The previous chapter introduced several topics in passing that this chapter covers more fully, such as making choices (branching) and creating complex expressions. In the previous chapter, I wanted to focus on the most basic syntax and operations in PHP, but I couldn’t avoid touching on more advanced topics. Now I can fill in the background that you need to use these powerful PHP features properly.

In this chapter, you will get a thorough grounding in how PHP programming works in practice and in how to control the flow of the program.

Expressions

Let’s start with the most fundamental part of any programming language: expressions.

An expression is a combination of values, variables, operators, and functions that results in a value. It’s familiar to anyone who has taken high-school algebra:

y = 3(abs(2x) + 4)

which in PHP would be:

$y = 3 * (abs(2 * $x) + 4);

The value returned (y, or $y in this case) can be a number, a string, or

a Boolean value (named after George Boole, a nineteenth-century English mathematician and

philosopher). By now, you should be familiar with the first two value

types, but I’ll explain the third.

TRUE or FALSE?

A basic Boolean value can be either TRUE or FALSE. For example, the expression “20 > 9”

(20 is greater than 9) is TRUE, and

the expression “5 == 6” (5 is equal to 6) is FALSE. (You can combine Boolean operations

using operators such as AND, OR, and XOR, which are covered later in this

chapter.)

Note

Note that I am using uppercase letters for the names TRUE and FALSE. This is because they are predefined constants in PHP. You can also use the

lowercase versions, if you prefer, as they are also predefined. In

fact, the lowercase versions are more stable, because PHP does not

allow you to redefine them; the uppercase ones may be

redefined—something you should bear in mind if you import third-party

code.

Example 4-1 shows some

simple expressions: the two I just mentioned, plus a couple more. For

each line, it prints out a letter between a and d,

followed by a colon and the result of the expressions. The <br> tag is there to create a line break

and thus separate the output into four lines in HTML.

Note

Now that we are fully into the age of HTML5, and XHTML is no longer being planned to supersede HTML, you

do not need to use the self-closing <br

/> form of the <br> tag, or any void elements (ones

without closing tags), because the / is now optional. Therefore, I have chosen

to use the simpler style in this book. If you ever made HTML non-void

tags self-closing (such as <div

/>), they will not work in HTML5 because the / will be ignored, and you will need to

replace them with, for example, <div>

... </div>. However, you must still use the <br /> form of HTML syntax when using

XHTML.

<?php echo "a: [" . (20 > 9) . "]<br>"; echo "b: [" . (5 == 6) . "]<br>"; echo "c: [" . (1 == 0) . "]<br>"; echo "d: [" . (1 == 1) . "]<br>"; ?>

The output from this code is as follows:

a: [1]

b: []

c: []

d: [1]Notice that both expressions a:

and d: evaluate to TRUE, which has a value of 1. But b:

and c:, which evaluate to FALSE, do not show any value, because in PHP

the constant FALSE is defined

as NULL, or nothing. To

verify this for yourself, you could enter the code in Example 4-2.

<?php // test2.php echo "a: [" . TRUE . "]<br>"; echo "b: [" . FALSE . "]<br>"; ?>

which outputs the following:

a: [1]

b: []By the way, in some languages FALSE may be defined as 0 or even −1, so it’s worth checking on its definition

in each language.

Literals and Variables

The simplest form of an expression is a literal, which simply

means something that evaluates to itself, such as the number 73 or the string "Hello". An expression could also simply be a

variable, which evaluates to the value that has been assigned to it.

They are both types of expressions, because they return a value.

Example 4-3 shows three literals and two variables, all of which return values, albeit of different types.

<?php $myname = "Brian"; $myage = 37; echo "a: " . 73 . "<br>"; // Numeric literal echo "b: " . "Hello" . "<br>"; // String literal echo "c: " . FALSE . "<br>"; // Constant literal echo "d: " . $myname . "<br>"; // String variable echo "e: " . $myage . "<br>"; // Numeric variable ?>

And, as you’d expect, you see a return value from all of these

with the exception of c:, which

evaluates to FALSE, returning nothing

in the following output:

a: 73

b: Hello

c:

d: Brian

e: 37In conjunction with operators, it’s possible to create more complex expressions that evaluate to useful results.

When you combine assignment or control-flow constructs with expressions, the result is

a statement. Example 4-4 shows one of each. The first

assigns the result of the expression 366 -

$day_number to the variable $days_to_new_year, and the second outputs a

friendly message only if the expression $days_to_new_year < 30 evaluates to

TRUE.

Operators

PHP offers a lot of powerful operators that range from arithmetic, string, and logical operators to assignment, comparison, and more (see Table 4-1).

Operator | Description | Example |

Arithmetic |

| |

Array |

| |

Assignment |

| |

Bitwise |

| |

Comparison |

| |

Execution |

| |

Increment/decrement |

| |

Logical |

| |

String |

|

Each operator takes a different number of operands:

Unary operators, such as incrementing (

$a++) or negation (-$a), which take a single operand.Binary operators, which represent the bulk of PHP operators, including addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

One ternary operator, which takes the form

? x : y. It’s a terse, single-lineifstatement that chooses between two expressions, depending on the result of a third one.

Operator Precedence

If all operators had the same precedence, they would be processed in the order in which they are encountered. In fact, many operators do have the same precedence, so let’s look at a few in Example 4-5.

Here you will see that although the numbers (and their preceding

operators) have been moved, the result of each expression is the value

7, because the plus and minus

operators have the same precedence. We can try the same thing with

multiplication and division (see Example 4-6).

1 * 2 * 3 / 4 * 5 2 / 4 * 5 * 3 * 1 5 * 2 / 4 * 1 * 3

Here the resulting value is always 7.5. But things change when we mix operators

with different precedencies in an expression, as in

Example 4-7.

1 + 2 * 3 − 4 * 5 2 − 4 * 5 * 3 + 1 5 + 2 − 4 + 1 * 3

If there were no operator precedence, these three expressions

would evaluate to 25, −29, and 12, respectively. But because multiplication

and division take precedence over addition and subtraction, there are

implied parentheses around these parts of the expressions, which would

look like Example 4-8 if

they were visible.

1 + (2 * 3) − (4 * 5) 2 − (4 * 5 * 3) + 1 5 + 2 − 4 + (1 * 3)

Clearly, PHP must evaluate the subexpressions within parentheses first to derive the semi-completed expressions in Example 4-9.

1 + (6) − (20) 2 − (60) + 1 5 + 2 − 4 + (3)

The final results of these expressions are −13, −57,

and 6, respectively (quite different

from the results of 25, −29, and 12

that we would have seen had there been no operator precedence).

Of course, you can override the default operator precedence by inserting your own parentheses and forcing the original results that we would have seen had there been no operator precedence (see Example 4-10).

((1 + 2) * 3 − 4) * 5 (2 − 4) * 5 * 3 + 1 (5 + 2 − 4 + 1) * 3

With parentheses correctly inserted, we now see the values

25, −29, and 12, respectively.

Table 4-2 lists PHP’s operators in order of precedence from high to low.

Associativity

We’ve been looking at processing expressions from left to right, except where operator precedence is in effect. But some operators require processing from right to left, and this direction of processing is called the operator’s associativity. For some operators there is no associativity.

Associativity becomes important in cases in which you do not explicitly force precedence, so you need to be aware of the default actions of operators, as detailed in Table 4-3, which lists operators and their associativity.

Operator | Description | Associativity |

| Create a new object | None |

| Comparison | None |

| Logical NOT | Right |

| Bitwise NOT | Right |

| Increment and decrement | Right |

| Cast to an integer | Right |

| Cast to a floating-point number | Right |

| Cast to a string | Right |

| Cast to an array | Right |

| Cast to an object | Right |

| Inhibit error reporting | Right |

| Assignment | Right |

| Assignment | Right |

| Addition and unary plus | Left |

| Subtraction and negation | Left |

| Multiplication | Left |

| Division | Left |

| Modulus | Left |

| String concatenation | Left |

| Bitwise | Left |

| Ternary | Left |

| Logical | Left |

| Separator | Left |

For example, let’s take a look at the assignment operator in Example 4-11, where three variables are

all set to the value 0.

This multiple assignment is possible only if the rightmost part of the expression is evaluated first and then processing continues in a right-to-left direction.

Note

As a beginner to PHP, you should avoid the potential pitfalls of operator associativity by always nesting your subexpressions within parentheses to force the order of evaluation. This will also help other programmers who may have to maintain your code to understand what is happening.

Relational Operators

Relational operators test two operands and return a Boolean result of either

TRUE or FALSE. There are three types of relational

operators: equality,

comparison, and

logical.

Equality

As we’ve already encountered a few times in this chapter, the equality

operator is == (two equals signs).

It is important not to confuse it with the = (single equals sign) assignment operator.

In Example 4-12, the

first statement assigns a value and the second tests it for

equality.

<?php $month = "March"; if ($month == "March") echo "It's springtime"; ?>

As you see, by returning either TRUE or FALSE, the equality operator enables you to

test for conditions using, for example, an if statement. But that’s not the whole

story, because PHP is a loosely typed language. If the two operands of

an equality expression are of different types, PHP will convert them

to whatever type makes best sense to it.

For example, any strings composed entirely of numbers will be

converted to numbers whenever compared with a number. In Example 4-13, $a and $b

are two different strings, and we would therefore expect neither of

the if statements to output a

result.

<?php $a = "1000"; $b = "+1000"; if ($a == $b) echo "1"; if ($a === $b) echo "2"; ?>

However, if you run the example, you will see that it outputs

the number 1, which means that the

first if statement evaluated to

TRUE. This is because both strings

were first converted to numbers, and 1000 is the same numerical value as +1000.

In contrast, the second if

statement uses the identity operator—three equals

signs in a row—which prevents PHP from automatically converting types.

$a and $b are therefore compared as strings and are

now found to be different, so nothing is output.

As with forcing operator precedence, whenever you have any doubt about how PHP will convert operand types, you can use the identity operator to turn this behavior off.

In the same way that you can use the equality operator to test

for operands being equal, you can test for them

not being equal using !=, the

inequality operator. Take a look at Example 4-14, which is a

rewrite of Example 4-13 in

which the equality and identity operators have been replaced with

their inverses.

<?php $a = "1000"; $b = "+1000"; if ($a != $b) echo "1"; if ($a !== $b) echo "2"; ?>

And, as you might expect, the first if statement does not output the number

1, because the code is asking

whether $a and $b are not equal to

each other numerically.

Instead, it outputs the number 2, because the second if statement is asking whether $a and $b

are not identical to each other in their present

operand types, and the answer is TRUE; they are not the same.

Comparison operators

Using comparison operators, you can test for more than just equality and inequality.

PHP also gives you > (is greater than), < (is less than), >= (is greater than or equal to), and

<= (is less than or equal to) to

play with. Example 4-15 shows

these operators in use.

<?php $a = 2; $b = 3; if ($a > $b) echo "$a is greater than $b<br>"; if ($a < $b) echo "$a is less than $b<br>"; if ($a >= $b) echo "$a is greater than or equal to $b<br>"; if ($a <= $b) echo "$a is less than or equal to $b<br>"; ?>

In this example, where $a is

2 and $b is 3,

the following is output:

2 is less than 3

2 is less than or equal to 3Try this example yourself, altering the values of $a and $b, to see the results. Try setting them to

the same value and see what happens.

Logical operators

Logical operators produce true-or-false results, and therefore are also known as Boolean operators. There are four of them (see Table 4-4).

You can see these operators used in Example 4-16. Note that the ! symbol is required by PHP in place of the

word NOT. Furthermore, the

operators can be lower- or uppercase.

<?php $a = 1; $b = 0; echo ($a AND $b) . "<br>"; echo ($a or $b) . "<br>"; echo ($a XOR $b) . "<br>"; echo !$a . "<br>"; ?>

This example outputs NULL,

1, 1, NULL,

meaning that only the second and third echo statements evaluate as TRUE. (Remember that NULL—or

nothing—represents a value of FALSE.) This is because the AND statement requires both operands to

be TRUE if it is

going to return a value of TRUE,

while the fourth statement performs a NOT on the value of $a, turning it from TRUE (a value of 1) to FALSE. If you wish to experiment with this,

try out the code, giving $a and

$b varying values of 1 and 0.

Note

When coding, remember to bear in mind that AND and

OR have lower precedence than the

other versions of the operators, && and ||. In complex expressions, it may be safer to use && and

|| for this reason.

The OR operator can cause

unintentional problems in if

statements, because the second operand will not be evaluated if the

first is evaluated as TRUE. In

Example 4-17, the function

getnext will never be called if

$finished has a value of 1.

If you need getnext to be

called at each if statement, you

could rewrite the code as has been done in Example 4-18.

<?php $gn = getnext(); if ($finished == 1 OR $gn == 1) exit; ?>

In this case, the code in function getnext will be executed and the value

returned will be stored in $gn

before the if statement.

Note

Another solution is to simply switch the two clauses to make

sure that getnext is executed, as

it will then appear first in the expression.

Table 4-5 shows

all the possible variations of using the logical operators. You should also note that !TRUE

equals FALSE and !FALSE equals TRUE.

Conditionals

Conditionals alter program flow. They enable you to ask questions about certain things and respond to the answers you get in different ways. Conditionals are central to dynamic web pages—the goal of using PHP in the first place—because they make it easy to create different output each time a page is viewed.

There are three types of non-looping conditionals: the if statement, the switch statement, and the ? operator. By non-looping,

I mean that the actions initiated by the statement take place and program

flow then moves on, whereas looping conditionals (which we’ll get to

shortly) execute code over and over until a condition has been met.

The if Statement

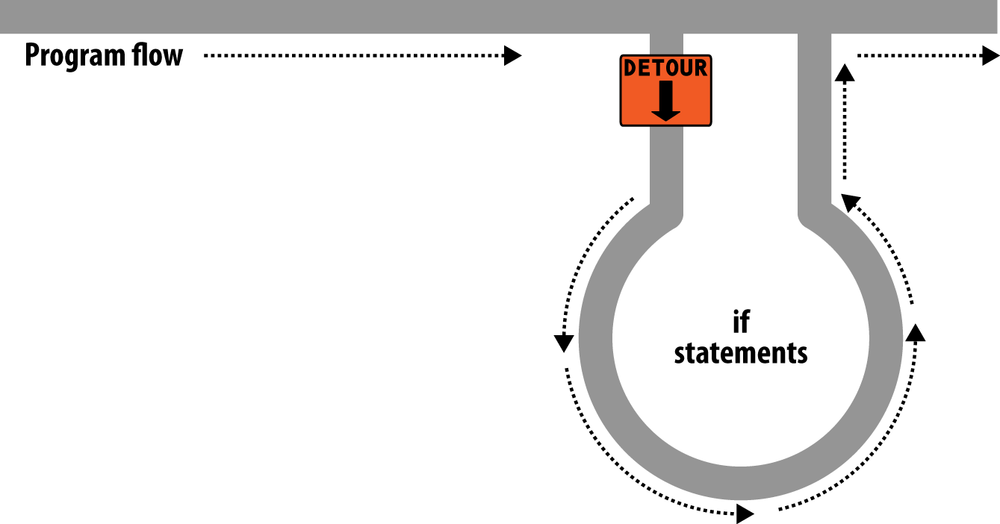

One way of thinking about program flow is to imagine it as a single-lane highway that you are driving along. It’s pretty much a straight line, but now and then you encounter various signs telling you where to go.

In the case of an if statement,

you could imagine coming across a detour sign that you have to follow if

a certain condition is TRUE. If so,

you drive off and follow the detour until you return to where it started

and then continue on your way in your original direction. Or, if the

condition isn’t TRUE, you ignore the

detour and carry on driving (see Figure 4-1).

The contents of the if

condition can be any valid PHP expression, including equality,

comparison, tests for 0 and NULL, and even the values returned by

functions (either built-in functions or ones that you write).

The actions to take when an if

condition is TRUE are generally

placed inside curly braces, { }.

However, you can ignore the braces if you have only a single statement

to execute. But if you always use curly braces, you’ll avoid having to

hunt down difficult-to-trace bugs, such as when you add an extra line to

a condition and it doesn’t get evaluated due to lack of braces. (Note

that for space and clarity, many of the examples in this book ignore

this suggestion and omit the braces for single statements.)

In Example 4-19, imagine that it is the end of the month and all your bills have been paid, so you are performing some bank account maintenance.

<?php

if ($bank_balance < 100)

{

$money = 1000;

$bank_balance += $money;

}

?>In this example, you are checking your balance to see whether it is less than $100 (or whatever your currency is). If so, you pay yourself $1,000 and then add it to the balance. (If only making money were that simple!)

If the bank balance is $100 or greater, the conditional statements are ignored and program flow skips to the next line (not shown).

In this book, opening curly braces generally start on a new line. Some people like to place the first curly brace to the right of the conditional expression; others start a new line with it. Either of these is fine, because PHP allows you to set out your whitespace characters (spaces, newlines, and tabs) any way you choose. However, you will find your code easier to read and debug if you indent each level of conditionals with a tab.

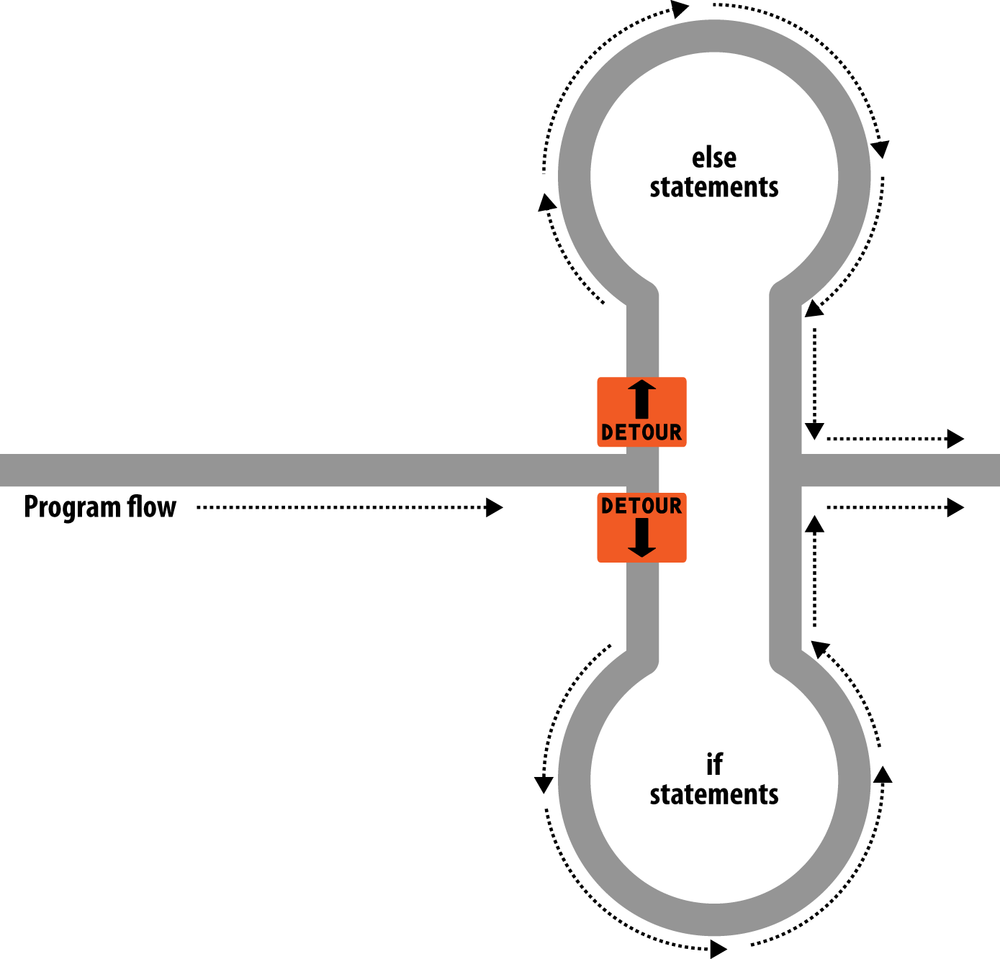

The else Statement

Sometimes when a conditional is not TRUE, you may not want to continue on to the

main program code immediately but might wish to do something else

instead. This is where the else

statement comes in. With it, you can set up a second detour on your

highway, as in Figure 4-2.

With an if ... else statement,

the first conditional statement is executed if the condition is TRUE. But if it’s FALSE, the second one is executed. One of the

two choices must be executed. Under no circumstance

can both (or neither) be executed. Example 4-20 shows the use of

the if ... else structure.

<?php

if ($bank_balance < 100)

{

$money = 1000;

$bank_balance += $money;

}

else

{

$savings += 50;

$bank_balance −= 50;

}

?>In this example, now that you’ve ascertained that you have $100 or

more in the bank, the else statement

is executed, by which you place some of this money into your savings

account.

As with if statements, if your

else has only one conditional

statement, you can opt to leave out the curly braces. (Curly braces are

always recommended, though. First, they make the code easier to

understand. Second, they let you easily add more statements to the

branch later.)

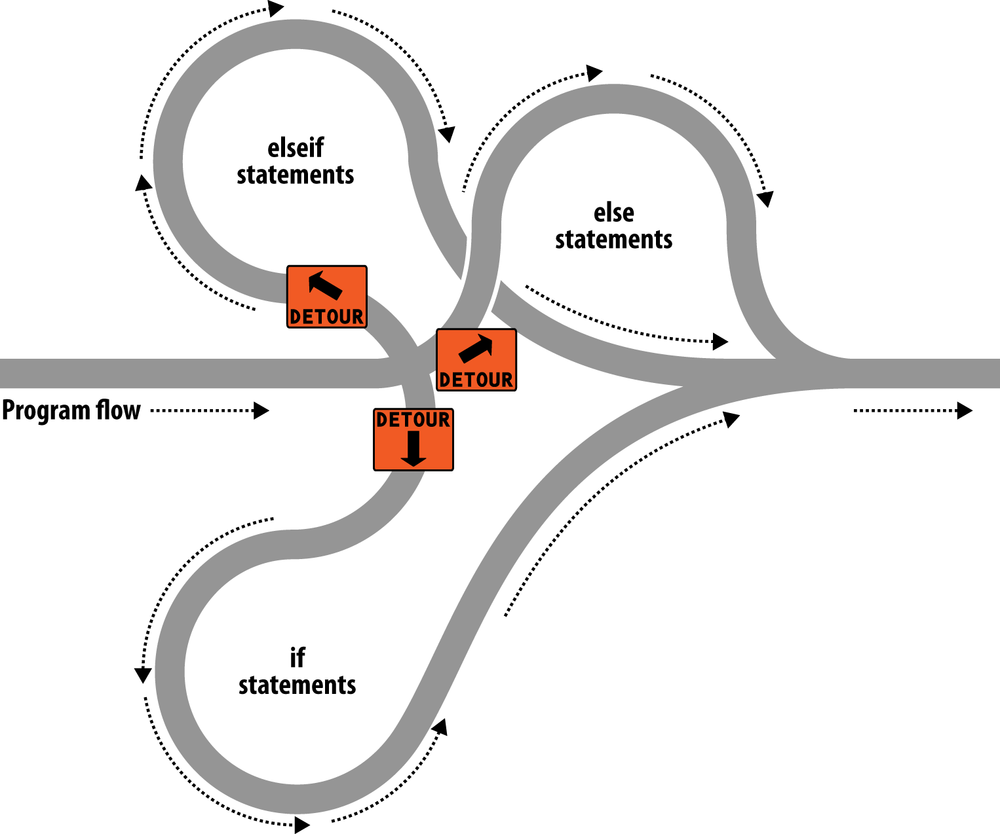

The elseif Statement

There are also times when you want a number of different possibilities to

occur, based upon a sequence of conditions. You can achieve this using

the elseif statement. As you might

imagine, it is like an else

statement, except that you place a further conditional expression prior

to the conditional code. In Example 4-21, you can see a

complete if ... elseif ... else

construct.

<?php

if ($bank_balance < 100)

{

$money = 1000;

$bank_balance += $money;

}

elseif ($bank_balance > 200)

{

$savings += 100;

$bank_balance −= 100;

}

else

{

$savings += 50;

$bank_balance −= 50;

}

?>In the example, an elseif

statement has been inserted between the if and else

statements. It checks whether your bank balance exceeds $200 and, if so,

decides that you can afford to save $100 of it this month.

Although I’m starting to stretch the metaphor a bit too far, you can imagine this as a multi-way set of detours (see Figure 4-3).

Note

An else statement closes

either an if ... else or an

if ... elseif ... else statement.

You can leave out a final else if

it is not required, but you cannot have one before an elseif; neither can you have an elseif before an if statement.

You may have as many elseif

statements as you like. But as the number of elseif statements increases, you would

probably be better advised to consider a switch statement if it fits your needs. We’ll

look at that next.

The switch Statement

The switch statement is

useful in cases in which one variable or the result of an

expression can have multiple values, which should each trigger a

different function.

For example, consider a PHP-driven menu system that passes a

single string to the main menu code according to what the user requests.

Let’s say the options are Home, About, News, Login, and Links, and we

set the variable $page to one of

these, according to the user’s input.

If we write the code for this using if

... elseif ... else, it might look like Example 4-22.

<?php if ($page == "Home") echo "You selected Home"; elseif ($page == "About") echo "You selected About"; elseif ($page == "News") echo "You selected News"; elseif ($page == "Login") echo "You selected Login"; elseif ($page == "Links") echo "You selected Links"; ?>

If we use a switch statement,

the code might look like Example 4-23.

<?php

switch ($page)

{

case "Home":

echo "You selected Home";

break;

case "About":

echo "You selected About";

break;

case "News":

echo "You selected News";

break;

case "Login":

echo "You selected Login";

break;

case "Links":

echo "You selected Links";

break;

}

?>As you can see, $page is

mentioned only once at the start of the switch statement. Thereafter, the case command checks for matches. When one

occurs, the matching conditional statement is executed. Of course, in a

real program you would have code here to display or jump to a page,

rather than simply telling the user what was selected.

Note

With switch statements, you

do not use curly braces inside case commands.

Instead, they commence with a colon and end with the break statement. The entire list of cases in

the switch statement is enclosed in

a set of curly braces, though.

Breaking out

If you wish to break out of the switch statement because a condition has

been fulfilled, use the break

command. This command tells PHP to break out of the switch and jump to the following

statement.

If you were to leave out the break commands in Example 4-23 and the case of Home evaluated to be TRUE, all five cases would then be executed.

Or if $page had the value News, then all the case commands from then on would execute.

This is deliberate and allows for some advanced programming, but

generally you should always remember to issue a break command every time a set of case conditionals has finished executing. In

fact, leaving out the break

statement is a common error.

Default action

A typical requirement in switch statements is to fall back on a

default action if none of the case

conditions are met. For example, in the case of the menu code in Example 4-23, you could add the code in Example 4-24 immediately before

the final curly brace.

default:

echo "Unrecognized selection";

break;Although a break command is

not required here because the default is the final sub-statement, and

program flow will automatically continue to the closing curly brace,

should you decide to place the default statement higher up it would

definitely need a break command to

prevent program flow from dropping into the following statements.

Generally, the safest practice is to always include the break command.

Alternative syntax

If you prefer, you may replace the first curly brace in a

switch statement with a single

colon, and the final curly brace with an endswitch command,

as in Example 4-25. However,

this approach is not commonly used and is mentioned here only in case

you encounter it in third-party code.

The ? Operator

One way of avoiding the verbosity of if and

else statements is to use the more

compact ternary operator, ?, which is

unusual in that it takes three operands rather than the typical

two.

We briefly came across this in Chapter 3 in the discussion about the difference

between the print and echo statements as an example of an operator type that works well with print but not echo.

The ? operator is passed an

expression that it must evaluate, along with two statements to execute:

one for when the expression evaluates to TRUE, the other for when it is FALSE. Example 4-26 shows code we might use for

writing a warning about the fuel level of a car to its digital

dashboard.

<?php echo $fuel <= 1 ? "Fill tank now" : "There's enough fuel"; ?>

In this statement, if there is one gallon or less of fuel (i.e.,

if $fuel is set to 1 or less), the string Fill tank now is returned to the preceding

echo statement. Otherwise, the string

There's enough fuel is returned. You

can also assign the value returned in a ? statement to a variable (see Example 4-27).

<?php $enough = $fuel <= 1 ? FALSE : TRUE; ?>

Here $enough will be assigned

the value TRUE only when there is

more than a gallon of fuel; otherwise, it is assigned the value FALSE.

If you find the ? operator

confusing, you are free to stick to if statements, but you should be familiar with

it, because you’ll see it in other people’s code. It can be hard to

read, because it often mixes multiple occurrences of the same variable.

For instance, code such as the following is quite popular:

$saved = $saved >= $new ? $saved : $new;

If you take it apart carefully, you can figure out what this code does:

$saved = // Set the value of $saved to...

$saved >= $new // Check $saved against $new

? // Yes, comparison is true ...

$saved // ... so assign the current value of $saved

: // No, comparison is false ...

$new; // ... so assign the value of $newIt’s a concise way to keep track of the largest value that you’ve

seen as a program progresses. You save the largest value in $saved and compare it to $new each time you get a new value.

Programmers familiar with the ?

operator find it more convenient than if statements for such short comparisons. When

not used for writing compact code, it is typically used to make some

decision inline, such as when you are testing whether a variable is set

before passing it to a function.

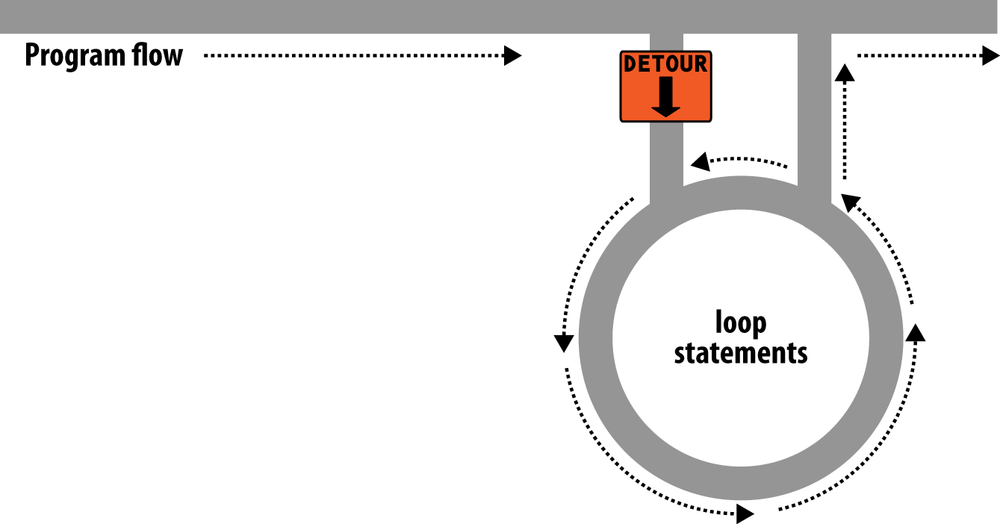

Looping

One of the great things about computers is that they can repeat calculating tasks quickly and tirelessly. Often you may want a program to repeat the same sequence of code again and again until something happens, such as a user inputting a value or reaching a natural end. PHP’s various loop structures provide the perfect way to do this.

To picture how this works, take a look at Figure 4-4. It is much the same

as the highway metaphor used to illustrate if statements, except that the detour also has a

loop section that—once a vehicle has entered—can be exited only under the

right program conditions.

while Loops

Let’s turn the digital car dashboard in Example 4-26 into a loop that continuously

checks the fuel level as you drive, using a while loop (Example 4-28).

<?php

$fuel = 10;

while ($fuel > 1)

{

// Keep driving ...

echo "There's enough fuel";

}

?>Actually, you might prefer to keep a green light lit rather than

output text, but the point is that whatever positive indication you wish

to make about the level of fuel is placed inside the while loop. By the way, if you try this

example for yourself, note that it will keep printing the string until

you click the Stop button in your browser.

Note

As with if statements, you

will notice that curly braces are required to hold the statements inside

the while statements, unless

there’s only one.

For another example of a while

loop that displays the 12 times table, see Example 4-29.

<?php

$count = 1;

while ($count <= 12)

{

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12 . "<br>";

++$count;

}

?>Here the variable $count is

initialized to a value of 1, then a while loop is started with the comparative

expression $count <= 12. This loop

will continue executing until the variable is greater than 12. The

output from this code is as follows:

1 times 12 is 12

2 times 12 is 24

3 times 12 is 36

and so on...Inside the loop, a string is printed along with the value of

$count multiplied by 12. For

neatness, this is also followed with a <br> tag to force a new line. Then

$count is incremented, ready for the

final curly brace that tells PHP to return to the start of the

loop.

At this point, $count is again

tested to see whether it is greater than 12. It isn’t, but it now has

the value 2, and after another 11

times around the loop, it will have the value 13. When that happens, the code within the

while loop is skipped and execution

passes on to the code following the loop, which, in this case, is the

end of the program.

If the ++$count statement

(which could equally have been $count++) had not been there, this loop would

be like the first one in this section. It would never end and only the

result of 1 * 12 would be printed

over and over.

But there is a much neater way this loop can be written, which I think you will like. Take a look at Example 4-30.

<?php

$count = 0;

while (++$count <= 12)

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12 . "<br>";

?>In this example, it was possible to remove the ++$count statement from inside the while loop and place it directly into the

conditional expression of the loop. What now happens is that PHP

encounters the variable $count at the

start of each iteration of the loop and, noticing that it is prefaced

with the increment operator, first increments the variable and only then

compares it to the value 12. You can

therefore see that $count now has to

be initialized to 0, not 1, because it is incremented as soon as the

loop is entered. If you keep the initialization at 1, only results between 2 and 12 will be

output.

do ... while Loops

A slight variation to the while loop is the

do ... while loop, used when you want

a block of code to be executed at least once and made conditional only

after that. Example 4-31

shows a modified version of the code for the 12 times table that uses

such a loop.

<?php

$count = 1;

do

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12 . "<br>";

while (++$count <= 12);

?>Notice how we are back to initializing $count to 1

(rather than 0) because the code is

being executed immediately, without an opportunity to increment the

variable. Other than that, though, the code looks pretty similar.

Of course, if you have more than a single statement inside a

do ... while loop, remember to use

curly braces, as in Example 4-32.

<?php

$count = 1;

do {

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12;

echo "<br>";

} while (++$count <= 12);

?>for Loops

The final kind of loop statement, the for

loop, is also the most powerful, as it combines the abilities to set up

variables as you enter the loop, test for conditions while iterating

loops, and modify variables after each iteration.

Example 4-33 shows

how you could write the multiplication table program with a for loop.

<?php

for ($count = 1 ; $count <= 12 ; ++$count)

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12 . "<br>";

?>See how the entire code has been reduced to a single for statement containing a single conditional

statement? Here’s what is going on. Each for statement takes three parameters:

An initialization expression

A condition expression

A modification expression

These are separated by semicolons like this: for (expr1 ; expr2 ; expr3). At the start of the first iteration of the

loop, the initialization expression is executed. In the case of the

times table code, $count is

initialized to the value 1. Then,

each time around the loop, the condition expression (in this case,

$count <= 12) is tested, and the

loop is entered only if the condition is TRUE. Finally, at the end of each iteration,

the modification expression is executed. In the case of the times table

code, the variable $count is

incremented.

All this structure neatly removes any requirement to place the controls for a loop within its body, freeing it up just for the statements you want the loop to perform.

Remember to use curly braces with a for loop if it will contain more than one

statement, as in Example 4-34.

<?php

for ($count = 1 ; $count <= 12 ; ++$count)

{

echo "$count times 12 is " . $count * 12;

echo "<br>";

}

?>Let’s compare when to use for

and while loops. The for loop is explicitly designed around a

single value that changes on a regular basis. Usually you have a value

that increments, as when you are passed a list of user choices and want

to process each choice in turn. But you can transform the variable any

way you like. A more complex form of the for statement even lets you perform multiple

operations in each of the three parameters:

for ($i = 1, $j = 1 ; $i + $j < 10 ; $i++ , $j++)

{

// ...

}That’s complicated and not recommended for first-time users. The key is to distinguish commas from semicolons. The three parameters must be separated by semicolons. Within each parameter, multiple statements can be separated by commas. Thus, in the previous example, the first and third parameters each contain two statements:

$i = 1, $j = 1 // Initialize $i and $j $i + $j < 10 // Terminating condition $i++ , $j++ // Modify $i and $j at the end of each iteration

The main thing to take from this example is that you must separate the three parameter sections with semicolons, not commas (which should be used only to separate statements within a parameter section).

So, when is a while statement

more appropriate than a for

statement? When your condition doesn’t depend on a simple, regular

change to a variable. For instance, if you want to check for some

special input or error and end the loop when it occurs, use a while

statement.

Breaking Out of a Loop

Just as you saw how to break out of a switch statement, you can also break out of a

for loop using the same break command. This step can be necessary

when, for example, one of your statements returns an error and the loop

cannot continue executing safely.

One case in which this might occur is when writing a file returns an error, possibly because the disk is full (see Example 4-35).

<?php

$fp = fopen("text.txt", 'wb');

for ($j = 0 ; $j < 100 ; ++$j)

{

$written = fwrite($fp, "data");

if ($written == FALSE) break;

}

fclose($fp);

?>This is the most complicated piece of code that you have seen so

far, but you’re ready for it. We’ll look into the file handling commands

in a later chapter, but for now all you need to know is that the first

line opens the file text.txt for

writing in binary mode, and then returns a pointer to the file in the

variable $fp, which is used later to

refer to the open file.

The loop then iterates 100 times (from 0 to 99) writing the string

data to the file. After each write,

the variable $written is assigned a

value by the fwrite function

representing the number of characters correctly written. But if there is

an error, the fwrite function

assigns the value FALSE.

The behavior of fwrite makes it

easy for the code to check the variable $written to see whether it is set to FALSE and, if so, to break out of the loop to

the following statement closing the file.

If you are looking to improve the code, the line:

if ($written == FALSE) break;

can be simplified using the NOT

operator, like this:

if (!$written) break;

In fact, the pair of inner loop statements can be shortened to the following single statement:

if (!fwrite($fp, "data")) break;

The break command is even more

powerful than you might think because if you have code nested more than

one layer deep that you need to break out of, you can follow the

break command with a number to

indicate how many levels to break out of, like this:

break 2;

The continue Statement

The continue statement is a

little like a break

statement, except that it instructs PHP to stop processing the current

loop and to move right to its next iteration. So, instead of breaking

out of the whole loop, PHP exits only the current iteration.

This approach can be useful in cases where you know there is no

point continuing execution within the current loop and you want to save

processor cycles or prevent an error from occurring by moving right

along to the next iteration of the loop. In Example 4-36, a continue statement is used to prevent a

division-by-zero error from being issued when the variable $j has a value of 0.

<?php

$j = 10;

while ($j > −10)

{

$j--;

if ($j == 0) continue;

echo (10 / $j) . "<br>";

}

?>For all values of $j between

10 and −10, with the exception of 0, the result of calculating 10 divided by $j is displayed. But for the particular case

of $j being 0, the continue statement is issued and execution

skips immediately to the next iteration of the loop.

Implicit and Explicit Casting

PHP is a loosely typed language that allows you to declare a variable and its type simply by using it. It also automatically converts values from one type to another whenever required. This is called implicit casting.

However, there may be times when PHP’s implicit casting is not what you want. In Example 4-37, note that the inputs to the division are integers. By default, PHP converts the output to floating point so it can give the most precise value—4.66 recurring.

<?php $a = 56; $b = 12; $c = $a / $b; echo $c; ?>

But what if we had wanted $c to

be an integer instead? There are various ways in which we could achieve this, one of which is

to force the result of $a/$b to be cast to an integer value using the

integer cast type (int), like

this:

$c = (int) ($a / $b);

This is called explicit casting. Note that in order to ensure that the value of the entire

expression is cast to an integer, we place the expression within

parentheses. Otherwise, only the variable $a would have been cast to an integer—a

pointless exercise, as the division by $b would still have returned a floating-point

number.

Note

You can explicitly cast to the types shown in Table 4-6, but you can usually avoid having to use a

cast by calling one of PHP’s built-in functions. For example, to obtain

an integer value, you could use the intval function. As with some other sections in this book, this one is

mainly here to help you understand third-party code that you may

encounter.

PHP Dynamic Linking

Because PHP is a programming language, and the output from it can be completely different for each user, it’s possible for an entire website to run from a single PHP web page. Each time the user clicks on something, the details can be sent back to the same web page, which decides what to do next according to the various cookies and/or other session details it may have stored.

Although it is possible to build an entire website this way, it’s not recommended, because your source code will grow and grow and start to become unwieldy, as it has to account for every possible action a user could take.

Instead, it’s much more sensible to split your website development into different parts. For example, one distinct process is signing up for a website, along with all the checking this entails to validate an email address, determine whether a username is already taken, and so on.

A second module might well be one for logging users in before handing them off to the main part of your website. Then you might have a messaging module with the facility for users to leave comments, a module containing links and useful information, another to allow uploading of images, and more.

As long as you have created a way to track your user through your website by means of cookies or session variables (both of which we’ll look at more closely in later chapters), you can split up your website into sensible sections of PHP code, each one self-contained, and therefore treat yourself to a much easier future developing each new feature and maintaining old ones.

Dynamic Linking in Action

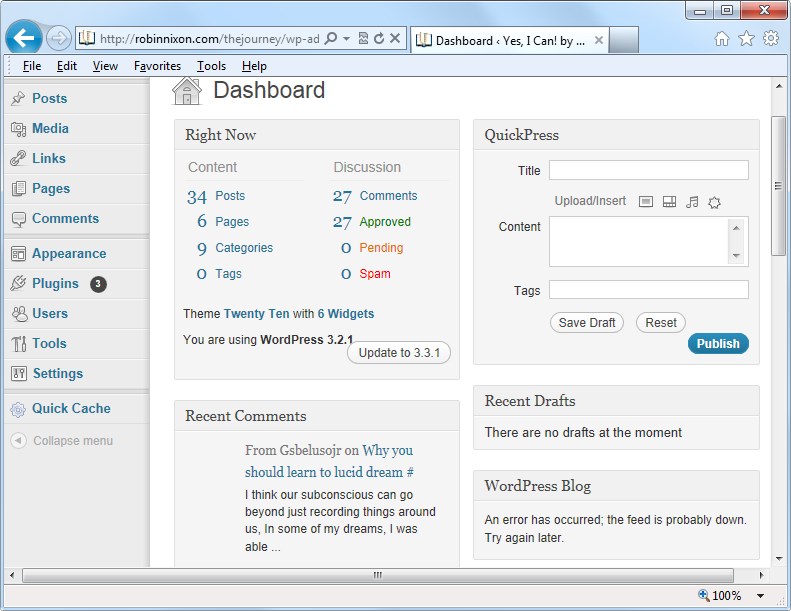

One of the more popular PHP-driven applications on the Web today is the blogging platform WordPress (see Figure 4-5). As a blogger or a blog reader, you might not realize it, but every major section has been given its own main PHP file, and a whole raft of generic, shared functions have been placed in separate files that are included by the main PHP pages as necessary.

The whole platform is held together with behind-the-scenes session tracking, so that you hardly know when you are transitioning from one subsection to another. So, as a web developer, if you want to tweak WordPress, it’s easy to find the particular file you need, modify it, and test and debug it without messing around with unconnected parts of the program.

Next time you use WordPress, keep an eye on your browser’s address bar, particularly if you are managing a blog, and you’ll notice some of the different PHP files that it uses.

This chapter has covered quite a lot of ground, and by now you should be able to put together your own small PHP programs. But before you do, and before proceeding with the following chapter on functions and objects, you may wish to test your new knowledge on the following questions.

Questions

What actual underlying values are represented by

TRUEandFALSE?What are the simplest two forms of expressions?

What is the difference between unary, binary, and ternary operators?

What is the best way to force your own operator precedence?

What is meant by operator associativity?

When would you use the

===(identity) operator?Name the three conditional statement types.

What command can you use to skip the current iteration of a loop and move on to the next one?

Why is a

forloop more powerful than awhileloop?How do

ifandwhilestatements interpret conditional expressions of different data types?

See Chapter 4 Answers in Appendix A for the answers to these questions.

Get Learning PHP, MySQL, JavaScript, CSS & HTML5, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.