Most applications will need to do more with data—typically, at least, they’ll store the data and present it back as appropriate. It’s time to extend this simple application so that it keeps track of who has stopped by, as well as greeting them. This requires using models. (The complete application is available in ch04/guestbook002.)

Warning

As the next chapter on scaffolding will make clear, in most application development you will likely want to create your models by letting Rails create a scaffold, since Rails won’t let you create a scaffold after a model with the same name already exists. Nonetheless, understanding the more manual approach will make it much easier to work on your applications in the long run.

Keeping track of visitors will mean setting up and using a database. In Rails 2.0.2 and

later, this should be easy when you’re in development mode, as Rails now defaults

to SQLite, which doesn’t require explicit configuration. (Earlier versions of Rails

required setting up MySQL, which does require configuration, which you'll still want to do

for deployment as discussed in Chapter 18.) To test whether SQLite is installed on your system, try issuing the command sqlite3 -help from the command line. If it’s there,

you’ll get a help message. If not, you’ll get an error, and you’ll

need to install SQLite.

Once the database engine is functioning, it’s time to create a model. Once

again, it’s easiest to use script/generate

to lay a foundation, and then add details to that foundation. This time,

we’ll create a simple model instead of a controller and call the model entry:

ruby script/generate model entry

exists app/models/

exists test/unit/

exists test/fixtures/

create app/models/entry.rb

create test/unit/entry_test.rb

create test/fixtures/entries.yml

create db/migrate

create db/migrate/20080718193908_create_entries.rbFor our immediate purposes, two of these files are critical. The first is app/models/entry.rb, which is where all of the Ruby logic for handling a person will go. The second, which defines the database structures and thus needs to be modified first, is in the db/migrate/ directory. It will have a name like [timestamp]_create_entries.rb, where [timestamp] is the date and time when it was created. It initially contains what’s shown in Example 4-4.

Example 4-4. The default migration for the entry model

1 class CreateEntries < ActiveRecord::Migration 2 def self.up 3 create_table :entries do |t| 4 5 t.timestamps 6 end 7 end 8 9 def self.down 10 drop_table :entries 11 end 12 end

There’s a lot to examine here before we start making changes. First, note on

line 1 that the class is called CreateEntries. The

model may be for a person, but the migration will create a table for more than one person.

Rails names tables (and migrations) for the plural, and can handle most common English

irregular pluralizations. (In cases where the singular and plural would be the same, you

end up with an s added for the plural, so deer become deers and sheep

become sheeps.) Many people find this natural, but other people hate it. For now, just go

with it—fighting Rails won’t make life any easier.

Also on line 1, you can see that this class inherits most of its functionality from

the Migration

class of ActiveRecord. ActiveRecord is the Rails library that handles all the database interactions.

(You can even use it separately from Rails, if you want to.)

There are two methods defined here, on lines 2 (self.up) and 9 (self.down). The self.up method will be called when you order the migration

run, and will create tables and columns your application needs. The self.down method will be called if you roll back the

migration—effectively it provides you with “undo”

functionality.

Note

This example takes the slow route through creating a model so you can see what happens. In the future, if you'd prefer to move more quickly, you can also add the names and types of data on the command line as you will do when generating scaffolding in the next chapter.

Both of these operate on a table called Entries—self.up creates it on line 3, while self.down destroys (drops) it on line 10. Note that the migration is not

concerned with what kind of database it works on. That’s all handled by the

configuration information. You’ll also see that migrations, despite working pretty

close to the database, don’t need to use SQL—though if you really want to

use SQL, it’s available.

Storing the names people enter into this very simple application requires adding a single column:

create_table :entries do |t|

t.string :name

t.timestamps

endThe new line refers to the table (t) and creates a

column of type string, which will be accessible as

:name.

Note

In older versions of Rails, that new line would have been written:

t.column :name, string

The old version still works, and you’ll definitely see migrations written this way in older applications and documents. The new form is a lot easier to read at a glance, though.

The t.timestamps line is there for housekeeping,

tracking “created at” and “updated at” information. Rails also

will automatically create a primary key, :id, for the table. Once

you’ve entered the new line (at line 4 of Example 4-4), you can run the migration with

the Rake tool:

$ rake db:migrate

(in /Users/simonstl/rails/guestbook)

== 20080814190623 CreateEntries: migrating =====================

-- create_table(:entries)

-> 0.0041s

== 20080814190623 CreateEntries: migrated (0.0044s) ============Rake is Ruby’s own version of the classic command-line Unix make tool, and Rails uses it for a wide variety of tasks. (For

a full list, try rake --tasks.)

In this case, the db:migrate task runs all of the previously

unapplied self.up migrations in your

application’s db/migrate/ folder. (db:rollback runs the self.down migrations corresponding to the previous run, giving you an undo

option.)

Now that the application has a table with a column for holding names, it’s time to turn to the app/models/entry.rb file. Its initial contents are very simple:

class Entry < ActiveRecord::Base end

The Entry class inherits from the ActiveRecord

library’s Base

class, but has no functionality of its

own. For right now, it can stay that way—Rails provides enough capability that

nothing more is needed.

Warning

Remember that the names in your models also need to stay away from the list of reserved words presented at http://wiki.rubyonrails.org/rails/pages/ReservedWords.

As you may have guessed, the controller is going to be the key component transferring data that comes in from the form to the model, and then it will be the key component transferring that data back out to the view for presentation to the user.

To get started, the controller will just blindly save new names to the model, using the code highlighted in Example 4-5.

Example 4-5. Using ActiveRecord to save a name

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

endThe highlighted line combines three separate operations into a single line of code, which might look like:

@myEntry = Entry.new

@myEntry.name = @name

@myEntry.saveThe first step creates a new variable, @myEntry,

and declares it to be a new Entry object. The next

line sets the name property of @myEntry—effectively setting the future value of the column named

“name” in the Entries table—to the @name value that came in through the form. The third line saves the

@myEntry object to the table.

The Entry.create

approach assumes you’re making a new object, takes the values to be

stored as named parameters, and then saves the object to the database.

Note

Both the create and the save

method return a boolean value indicating whether or not saving the value

to the database was successful. For most applications, you’ll want to test

this, and return an error if there was a failure.

These are the basic methods you’ll need to put information into your

databases with ActiveRecord. (There are many shortcuts and more elegant syntax, as the

next chapter will show.) This approach is also a bit too simple. If you visit http://localhost:3000/entries/sign_in/, you’ll see the same empty form

that was shown in Figure 4-1. However,

because @entry.create was called, an empty name will

have been written to the table. The log data that appears in the server’s

terminal window shows:

Entry Create (0.000522) INSERT INTO "entries" ("name", "updated_at",

"created_at") VALUES(NULL, '2008-08-14 19:13:58', '2008-08-14 19:13:58')The NULL is the problem here because it really doesn’t make sense to add a blank name every time someone loads the form without sending a value. On the bright side, we have evidence that Rails is putting information into the Entries table, and if we enter a name, say “Zaphod,” we can see the name being entered into the table:

Entry Create (0.000409) INSERT INTO "entries" ("name", "updated_at",

"created_at") VALUES('Zaphod', '2008-08-14 19:15:06', '2008-08-14 19:15:06')It’s easy to fix the controller so that NULLs aren’t stored—though as we’ll see in Chapter 7, this kind of validation code really belongs in the model. Two lines, highlighted in Example 4-6, will keep Rails from entering a lot of blank names.

Example 4-6. Keeping blanks from turning into permanent objects

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

if !@name.blank?

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

end

endNow Rails will check the @name variable to make

sure that it has a value before putting it into the database. !@name.blank?

will test for both nil values and blank entries. (blank is a Rails method extending Ruby's String objects. The ! at the beginning

means “not,” which ensure that only values that are not blank will be

accepted.)

If you want to get rid of the NULLs you put into the database, you can run rake

db:rollback and rake

db:migrate (or rake

db:migrate:redo to combine them) to drop and rebuild

the table with a clean copy.

== 1 CreateEntries: reverting ======================================= -- drop_table(:entries) -> 0.0029s == 1 CreateEntries: reverted (0.0031s) ============================== == 1 CreateEntries: migrating ======================================= -- create_table(:entries) -> 0.0039s == 1 CreateEntries: migrated (0.0041s) ==============================

If you want to enter a few names to put some data into the new table, go ahead. The next example will show how to get them out.

Storing data is a good thing, but only if you can get it out again. Fortunately, it’s not difficult for the controller to tell the model that it wants all the data, or for the view to render it. For a guestbook, it’s especially simple, as we just want all of the data every time.

Getting the data out of the model requires one line of additional code in the controller, highlighted in Example 4-7.

Example 4-7. A controller that also retrieves data from a model

class EntriesController < ApplicationController

def sign_in

@name = params[:visitor_name]

if !@name.blank? then

@entry = Entry.create({:name => @name})

end

@entries = Entry.find(:all)

end

endThe Entry object includes a find

method—like new and save, inherited from its parent ActiveRecord::Base class without any additional programming. If you run

this and look in the logs, you’ll see that Rails is actually making a SQL call to

populate the @entry array:

Entry Load (0.000633) SELECT * FROM "entries"

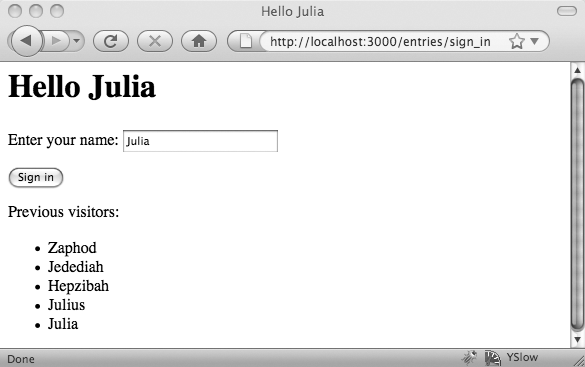

Next, the view, still in views/entries/sign_in.html.erb, can show the contents of that array, letting visitors to the site see who’s come by before, using the added lines shown in Example 4-8.

Example 4-8. Displaying existing users with a loop

<html> <head><title>Hello <%=h @name %></title></head> <body> <h1>Hello <%=h @name %></h1> <% form_tag :action => 'sign_in' do %> <p>Enter your name: <%= text_field_tag 'visitor_name', @name %></p> <%= submit_tag 'Sign in' %> <% end %><p>Previous visitors:</p><ul><% @entries.each do |entry| %><li><%=h entry.name %></li><% end %></ul></body> </html>

The loop here iterates over the @entries array,

running as many times as there are entries in @entries. @entries, of course, holds the

list of names previously entered, pulled from the database by the model that was called

by the controller in Example 4-7. For

each entry, the view adds a list item containing the name value, referenced here as entry.name. The result, depending on exactly what names you entered, will

look something like Figure 4-5.

It’s a lot of steps, yes, but fortunately you’ll be able to skip a lot of those steps as you move deeper into Rails. Building this guestbook didn’t look very much like the “complex-application-in-five–minutes” demonstrations that Rails’ promoters like to show off, but now you should understand what’s going on underneath the magic. After the apprenticeship, the next chapter will get into some journeyman fun.

Get Learning Rails: Live Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.