Chapter 4. How React Works

So far on your journey, you’ve brushed up on the latest syntax. You’ve reviewed the functional programming patterns that guided React’s creation. These steps have prepared you to take the next step, to do what you came here to do: to learn how React works. Let’s get into writing some real React code.

When you work with React, it’s more than likely that you’ll be creating your apps with JSX. JSX is a tag-based JavaScript syntax that looks a lot like HTML. It’s a syntax we’ll dive deep into in the next chapter and continue to use for the rest of the book. To truly understand React, though, we need to understand its most atomic units: React elements. From there, we’ll get into React elements. From there, we’ll get into React components by looking at how we can create custom components that compose other components and elements.

Page Setup

In order to work with React in the browser, we need to include two libraries: React and ReactDOM. React is the library for creating views. ReactDOM is the library used to actually render the UI in the browser. Both libraries are available as scripts from the unpkg CDN (links are included in the following code). Let’s set up an HTML document:

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><metacharset="utf-8"/><title>React Samples</title></head><body><!-- Target container --><divid="root"></div><!-- React library & ReactDOM (Development Version)--><scriptsrc="https://unpkg.com/react@16/umd/react.development.js"></script><scriptsrc="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@16/umd/react-dom.development.js"></script><script>// Pure React and JavaScript code</script></body></html>

These are the minimum requirements for working with React in the browser. You can place your JavaScript in a separate file, but it must be loaded somewhere in the page after React has been loaded. We’re going to be using the development version of React to see all of the error messages and warnings in the browser console. You can choose to use the minified production version using react.production.min.js and react-dom.production.min.js, which will strip away those warnings.

React Elements

HTML is simply a set of instructions that a browser follows when constructing the DOM. The elements that make up an HTML document become DOM elements when the browser loads HTML and renders the user interface.

Let’s say you have to construct an HTML hierarchy for a recipe. A possible solution for such a task might look something like this:

<sectionid="baked-salmon"><h1>Baked Salmon</h1><ulclass="ingredients"><li>2 lb salmon</li><li>5 sprigs fresh rosemary</li><li>2 tablespoons olive oil</li><li>2 small lemons</li><li>1 teaspoon kosher salt</li><li>4 cloves of chopped garlic</li></ul><sectionclass="instructions"><h2>Cooking Instructions</h2><p>Preheat the oven to 375 degrees.</p><p>Lightly coat aluminum foil with oil.</p><p>Place salmon on foil</p><p>Cover with rosemary, sliced lemons, chopped garlic.</p><p>Bake for 15-20 minutes until cooked through.</p><p>Remove from oven.</p></section></section>

In HTML, elements relate to one another in a hierarchy that resembles a family tree. We could say that the root element (in this case, a section) has three children: a heading, an unordered list of ingredients, and a section for the instructions.

In the past, websites consisted of independent HTML pages. When the user navigated these pages, the browser would request and load different HTML documents. The invention of AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) brought us the single-page application, or SPA. Since browsers could request and load tiny bits of data using AJAX, entire web applications could now run out of a single page and rely on JavaScript to update the user interface.

In an SPA, the browser initially loads one HTML document. As users navigate through the site, they actually stay on the same page. JavaScript destroys and creates a new user interface as the user interacts with the application. It may feel as though you’re jumping from page to page, but you’re actually still on the same HTML page, and JavaScript is doing the heavy lifting.

The DOM API is a collection of objects that

JavaScript can use to interact with the browser to modify the DOM. If

you’ve used document.createElement or document.appendChild, you’ve worked with the DOM API.

React is a library that’s designed to update the browser DOM for us. We no longer have to be concerned with the complexities associated with building high-performing SPAs because React can do that for us. With React, we do not interact with the DOM API directly. Instead, we provide instructions for what we want React to build, and React will take care of rendering and reconciling the elements we’ve instructed it to create.

The browser DOM is made up of DOM elements. Similarly, the React DOM is made up of React elements. DOM elements and React elements may look the same, but they’re actually quite different. A React element is a description of what the actual DOM element should look like. In other words, React elements are the instructions for how the browser DOM should be created.

We can create a React element to represent an h1 using

React.createElement:

React.createElement("h1",{id:"recipe-0"},"Baked Salmon");

The first argument defines the type of element we want to create.

In this case, we want to create an h1 element. The second argument

represents the element’s properties. This h1 currently has an id of

recipe-0. The third argument represents the element’s children: any

nodes that are inserted between the opening and closing tag (in this

case, just some text).

During rendering, React will convert this element to an actual DOM element:

<h1id="recipe-0">Baked Salmon</h1>

The properties are similarly applied to the new DOM element: the properties are added to the tag as attributes, and the child text is added as text within the element. A React element is just a JavaScript literal that tells React how to construct the DOM element.

If you were to log this element, it would look like this:

{$$typeof:Symbol(React.element),"type":"h1","key":null,"ref":null,"props":{id:"recipe-0",children:"Baked Salmon"},"_owner":null,"_store":{}}

This is the structure of a React element. There are fields that are used

by React: _owner, _store, and $$typeof. The key and ref fields are

important to React elements, but we’ll introduce those later. For now,

let’s take a closer look at the type and props fields.

The type property of the React element tells React what type of HTML

or SVG element to create. The props property represents the data and

child elements required to construct a DOM element. The children

property is for displaying other nested elements as text.

ReactDOM

Once we’ve created a React element, we’ll want to see it in the

browser. ReactDOM contains the tools necessary to render React elements

in the browser. ReactDOM is where we’ll find the render method.

We can render a React element, including its children, to the DOM with

ReactDOM.render. The element we want to render is passed as the

first argument, and the second argument is the target node, where we

should render the element:

constdish=React.createElement("h1",null,"Baked Salmon");ReactDOM.render(dish,document.getElementById("root"));

Rendering the title element to the DOM would add an h1 element to the

div with the id of root, which we would already have defined in

our HTML. We build this div inside the body tag:

<body><divid="root"><h1>Baked Salmon</h1></div></body>

Anything related to rendering elements to the DOM is found in the

ReactDOM package. In versions of React earlier than React 16, you

could only render one element to the DOM. Today, it’s possible to render

arrays as well. When the ability to do this was announced at ReactConf

2017, everyone clapped and screamed. It was a big deal. This is what

that looks like:

constdish=React.createElement("h1",null,"Baked Salmon");constdessert=React.createElement("h2",null,"Coconut Cream Pie");ReactDOM.render([dish,dessert],document.getElementById("root"));

This will render both of these elements as siblings inside of the root

container. We hope you just clapped and screamed!

In the next section, we’ll get an understanding of how to use

props.children.

Children

React renders child elements using props.children. In the previous

section, we rendered a text element as a child of the h1 element, and

thus props.children was set to Baked Salmon. We could render other

React elements as children, too, creating a tree of elements. This is why

we use the term element tree: the tree has one root element from which

many branches grow.

Let’s consider the unordered list that contains ingredients:

<ul><li>2 lb salmon</li><li>5 sprigs fresh rosemary</li><li>2 tablespoons olive oil</li><li>2 small lemons</li><li>1 teaspoon kosher salt</li><li>4 cloves of chopped garlic</li></ul>

In this sample, the unordered list is the root element, and it has six

children. We can represent this ul and its children with

React.createElement:

React.createElement("ul",null,React.createElement("li",null,"2 lb salmon"),React.createElement("li",null,"5 sprigs fresh rosemary"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 tablespoons olive oil"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 small lemons"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 teaspoon kosher salt"),React.createElement("li",null,"4 cloves of chopped garlic"));

Every additional argument sent to the createElement function is

another child element. React creates an array of these child elements

and sets the value of props.children to that array.

If we were to inspect the resulting React element, we would see each

list item represented by a React element and added to an array called

props.children. If you console log this element:

constlist=React.createElement("ul",null,React.createElement("li",null,"2 lb salmon"),React.createElement("li",null,"5 sprigs fresh rosemary"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 tablespoons olive oil"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 small lemons"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 teaspoon kosher salt"),React.createElement("li",null,"4 cloves of chopped garlic"));console.log(list);

The result will look like this:

{"type":"ul","props":{"children":[{"type":"li","props":{"children":"2 lb salmon"}…},{"type":"li","props":{"children":"5 sprigs fresh rosemary"}…},{"type":"li","props":{"children":"2 tablespoons olive oil"}…},{"type":"li","props":{"children":"2 small lemons"}…},{"type":"li","props":{"children":"1 teaspoon kosher salt"}…},{"type":"li","props":{"children":"4 cloves of chopped garlic"}…}]...}}

We can now see that each list item is a child. Earlier in this chapter,

we introduced HTML for an entire recipe rooted in a section element.

To create this using React, we’ll use a series of createElement calls:

React.createElement("section",{id:"baked-salmon"},React.createElement("h1",null,"Baked Salmon"),React.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},React.createElement("li",null,"2 lb salmon"),React.createElement("li",null,"5 sprigs fresh rosemary"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 tablespoons olive oil"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 small lemons"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 teaspoon kosher salt"),React.createElement("li",null,"4 cloves of chopped garlic")),React.createElement("section",{className:"instructions"},React.createElement("h2",null,"Cooking Instructions"),React.createElement("p",null,"Preheat the oven to 375 degrees."),React.createElement("p",null,"Lightly coat aluminum foil with oil."),React.createElement("p",null,"Place salmon on foil."),React.createElement("p",null,"Cover with rosemary, sliced lemons, chopped garlic."),React.createElement("p",null,"Bake for 15-20 minutes until cooked through."),React.createElement("p",null,"Remove from oven.")));

className in React

Any element that has an HTML class attribute is using className for

that property instead of class. Since class is a reserved word in

JavaScript, we have to use className to define the class attribute

of an HTML element.

This sample is what pure React looks like. Pure React is ultimately what

runs in the browser. A React app is a tree of React elements all

stemming from a single root element. React elements are the instructions

React will use to build a UI in the browser.

Constructing elements with data

The major advantage of using React is its ability to separate data from UI elements. Since React is just JavaScript, we can add JavaScript logic to help us build the React component tree. For example, ingredients can be stored in an array, and we can map that array to the React elements.

Let’s go back and think about the unordered list for a moment:

React.createElement("ul",null,React.createElement("li",null,"2 lb salmon"),React.createElement("li",null,"5 sprigs fresh rosemary"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 tablespoons olive oil"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 small lemons"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 teaspoon kosher salt"),React.createElement("li",null,"4 cloves of chopped garlic"));

The data used in this list of ingredients can easily be represented using a JavaScript array:

constitems=["2 lb salmon","5 sprigs fresh rosemary","2 tablespoons olive oil","2 small lemons","1 teaspoon kosher salt","4 cloves of chopped garlic"];

We want to use this data to generate the correct number of list items without having to hard-code each one. We can map over the array and create list items for as many ingredients as there are:

React.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},items.map(ingredient=>React.createElement("li",null,ingredient)));

This syntax creates a React element for each ingredient in the array. Each string is displayed in the list item’s children as text. The value for each ingredient is displayed as the list item.

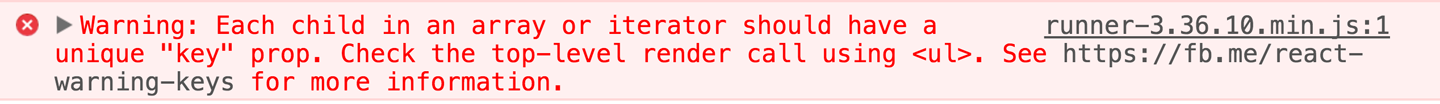

When running this code, you’ll see a console warning like the one shown in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. Console warning

When we build a list of child elements by iterating through an array,

React likes each of those elements to have a key property. The key

property is used by React to help it update the DOM efficiently. You can

make this warning go away by adding a unique key property to each of

the list item elements. You can use the array index for each ingredient

as that unique value:

React.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));

We’ll cover keys in more detail when we discuss JSX, but adding this to each list item will clear the console warning.

React Components

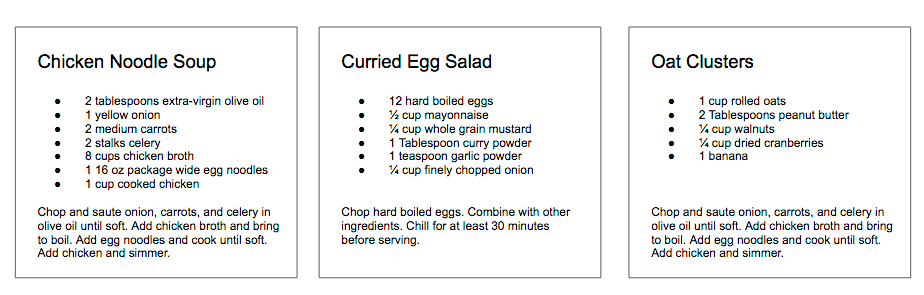

No matter its size, its contents, or what technologies are used to create it, a user interface is made up of parts. Buttons. Lists. Headings. All of these parts, when put together, make up a user interface. Consider a recipe application with three different recipes. The data is different in each box, but the parts needed to create a recipe are the same (see Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. Recipes app

In React, we describe each of these parts as a component. Components allow us to reuse the same structure, and then we can populate those structures with different sets of data.

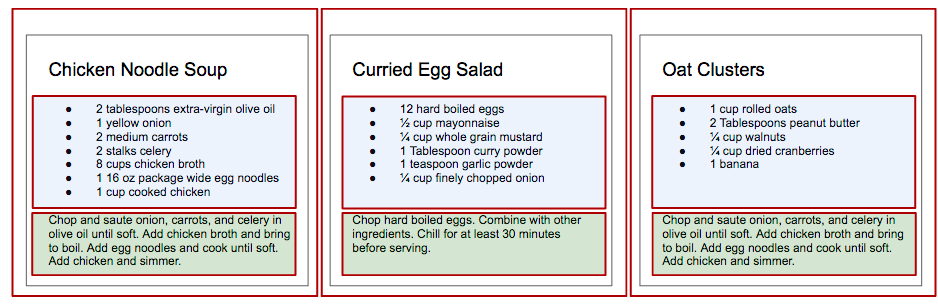

When considering a user interface you want to build with React, look for opportunities to break down your elements into reusable pieces. For example, the recipes in Figure 4-3 have a title, ingredients list, and instructions. All are part of a larger recipe or app component. We could create a component for each of the highlighted parts: ingredients, instructions, and so on.

Figure 4-3. Each component is outlined: App, IngredientsList, Instructions

Think about how scalable this is. If we want to display one recipe, our component structure will support this. If we want to display 10,000 recipes, we’ll just create 10,000 new instances of that component.

We’ll create a component by writing a function. That function will

return a reusable part of a user interface. Let’s create a function that

returns an unordered list of ingredients. This time, we’ll make dessert

with a function called IngredientsList:

functionIngredientsList(){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},React.createElement("li",null,"1 cup unsalted butter"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 cup crunchy peanut butter"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 cup brown sugar"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 cup white sugar"),React.createElement("li",null,"2 eggs"),React.createElement("li",null,"2.5 cups all purpose flour"),React.createElement("li",null,"1 teaspoon baking powder"),React.createElement("li",null,"0.5 teaspoon salt"));}ReactDOM.render(React.createElement(IngredientsList,null,null),document.getElementById("root"));

The component’s name is IngredientsList, and the function outputs

elements that look like this:

<IngredientsList><ulclassName="ingredients"><li>1 cup unsalted butter</li><li>1 cup crunchy peanut butter</li><li>1 cup brown sugar</li><li>1 cup white sugar</li><li>2 eggs</li><li>2.5 cups all purpose flour</li><li>1 teaspoon baking powder</li><li>0.5 teaspoon salt</li></ul></IngredientsList>

This is pretty cool, but we’ve hardcoded this data into the component. What if we could build one component and then pass data into that component as properties? And then what if that component could render the data dynamically? Maybe someday that will happen!

Just kidding—that day is now. Here’s an array of secretIngredients needed to put

together a recipe:

constsecretIngredients=["1 cup unsalted butter","1 cup crunchy peanut butter","1 cup brown sugar","1 cup white sugar","2 eggs","2.5 cups all purpose flour","1 teaspoon baking powder","0.5 teaspoon salt"];

Then we’ll adjust the IngredientsList component to map over these

items, constructing an li for however many items are in the items

array:

functionIngredientsList(){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));}

Then we’ll pass those secretIngredients as a property called items, which is the second argument used in createElement:

ReactDOM.render(React.createElement(IngredientsList,{items:secretIngredients},null),document.getElementById("root"));

Now, let’s look at the DOM. The data property items is an array with

eight ingredients. Because we made the li tags using a loop, we were

able to add a unique key using the index of the loop:

<IngredientsListitems="[...]"><ulclassName="ingredients"><likey="0">1 cup unsalted butter</li><likey="1">1 cup crunchy peanut butter</li><likey="2">1 cup brown sugar</li><likey="3">1 cup white sugar</li><likey="4">2 eggs</li><likey="5">2.5 cups all purpose flour</li><likey="6">1 teaspoon baking powder</li><likey="7">0.5 teaspoon salt</li></ul></IngredientsList>

Creating our component this way will make the component more flexible.

Whether the items array is one item or a hundred items long, the component

will render each as a list item.

Another adjustment we can make here is to reference the items array from

React props. Instead of mapping over the global items, we’ll make

items available on the props object. Start by passing props to the

function, then mapping over props.items:

functionIngredientsList(props){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},props.items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));}

We could also clean up the code a bit by destructuring items from

props:

functionIngredientsList({items}){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));}

Everything that’s associated with the UI for IngredientsList is

encapsulated into one component. Everything we need is right there.

React Components: A Historical Tour

Before there were function components, there were other ways to create components. While we won’t spend a great deal of time on these approaches, it’s important to understand the history of React components, particularly when dealing with these APIs in legacy codebases. Let’s take a little historical tour of React APIs of times gone by.

Tour stop 1: createClass

When React was first made open source in 2013, there was one way to create a

component: createClass. The use of React.createClass to create a

component looks like this:

constIngredientsList=React.createClass({displayName:"IngredientsList",render(){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},this.props.items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));}});

Components that used createClass would have a render() method that

described the React element(s) that should be returned and rendered. The

idea of the component was the same: we’d describe a reusable bit of UI

to render.

In React 15.5 (April 2017), React started throwing warnings if

createClass was used. In React 16 (September 2017),

React.createClass was officially deprecated and was moved to its own

package, create-react-class.

Tour stop 2: class components

When class syntax was added to JavaScript with ES 2015, React

introduced a new method for creating React components. The

React.Component API allowed you to use class syntax to create a new

component instance:

classIngredientsListextendsReact.Component{render(){returnReact.createElement("ul",{className:"ingredients"},this.props.items.map((ingredient,i)=>React.createElement("li",{key:i},ingredient)));}}

It’s still possible to create a React component using class syntax, but

be forewarned that React.Component is on the path to deprecation as well.

Although it’s still supported, you can expect this to go the way of

React.createClass, another old friend who shaped you but who you won’t

see as often because they moved away and you moved on. From now on,

we’ll use functions to create components in this book and only briefly

point out older patterns for reference.

Get Learning React, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.