Services

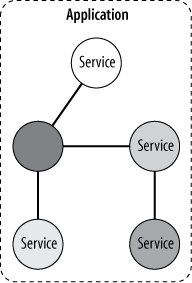

A service is a unit of functionality exposed to the world. In that respect, it is the next evolutionary step in the long journey from functions to objects to components to services. Service orientation (SO) is an abstract set of principles and best practices for building service-oriented applications. Appendix A provides a concise overview and outlines the motivation for using this methodology. The rest of this book assumes you are familiar with these principles. A service-oriented application aggregates services into a single logical application, similar to the way a component-oriented application aggregates components and an object-oriented application aggregates objects, as shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. A service-oriented application

The services can be local or remote, can be developed by multiple parties using any technology, can be versioned independently, and can even execute on different timelines. Inside a service, you will find concepts such as languages, technologies, platforms, versions, and frameworks, yet between services, only prescribed communication patterns are allowed.

The client of a service is merely the party consuming its functionality. The client can be literally anything—for instance, a Windows Forms, WPF, or Silverlight class, an ASP.NET page, or another service.

Clients and services interact by sending and receiving messages. Messages may be transferred ...