Per-Call Services

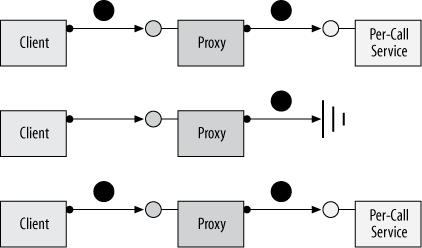

When the service type is configured for per-call activation, a service instance (the CLR object) exists only while a client call is in progress. Every client request (that is, a method call on the WCF contract) gets a new dedicated service instance. The following list explains how per-call activation works, and the steps are illustrated in Figure 4-1:

The client calls the proxy and the proxy forwards the call to the service.

WCF creates a new context with a new service instance and calls the method on it.

When the method call returns, if the object implements

IDisposable, WCF callsIDisposable.Dispose()on it. WCF then destroys the context.The client calls the proxy and the proxy forwards the call to the service.

WCF creates an object and calls the method on it.

Figure 4-1. Per-call instantiation mode

Disposing of the service instance is an interesting point. As I

just mentioned, if the service supports the IDisposable interface, WCF will automatically

call the Dispose() method, allowing

the service to perform any required cleanup. Note that Dispose() is called on the same thread that

dispatched the original method call, and that Dispose() has an operation context

(presented later). Once Dispose() is

called, WCF disconnects the instance from the rest of the WCF

infrastructure, making it a candidate for garbage collection.

Benefits of Per-Call Services

In the classic client/server ...