Chapter 1. Meta-Principles

The proper application of any methodology first requires a clear understanding and separation of principles from tactics.

Principles guide what you do. Tactics show you how.

The essence of Running Lean can be distilled into three steps:

Document your Plan A.

Identify the riskiest parts of your plan.

Systematically test your plan.

In this chapter, we’ll cover these meta-principles. The rest of the book will focus on the reduction of these meta-principles to practice.

Step 1: Document Your Plan A

There Is an “I” in Vision

All men dream: but not equally. Those that dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible.

—T.E. Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia”

Everyone gets hit by ideas when they least expect them (in the shower, while driving, etc.). Most people ignore them. Entrepreneurs choose to act on them.

While passion and determination are attributes that are essential in order to drive a vision to its full potential, if they are left unchecked, they can also turn the journey into a faith-based one driven by dogma.

Reasonably smart people can rationalize anything, but entrepreneurs are especially gifted at this.

Most entrepreneurs start with a strong initial vision and a Plan A for realizing that vision. Unfortunately, most Plan A’s don’t work.

While a strong vision is required to create a mantra and make meaning, a Lean Startup strives to uphold a strong vision with facts, not faith. It is important to accept that your initial vision is built largely on untested assumptions (or hypotheses). Running Lean helps you systematically test and refine that initial vision.

Capture Your Business Model Hypotheses

Too many founders carry their hypotheses in their heads alone, which, though the fastest way to iterate, only helps to further support their own “reality distortion fields.”

The first step is writing down your initial vision and then sharing it with at least one other person.

Traditionally, business plans have been used for this purpose. But, while writing a business plan is a good exercise for the entrepreneur, it falls short of its true purpose: Facilitating conversations with people other than yourself.

Additionally, since most Plan As are likely to be proven wrong anyway, you need something less static and rigid than a business plan. Taking several weeks or months to write a 60-page business plan largely built on untested hypotheses is a form of waste.

Waste is any human activity which absorbs resources but creates no value.

—James P. Womak and Daniel T. Jones, Lean Thinking (Free Press)

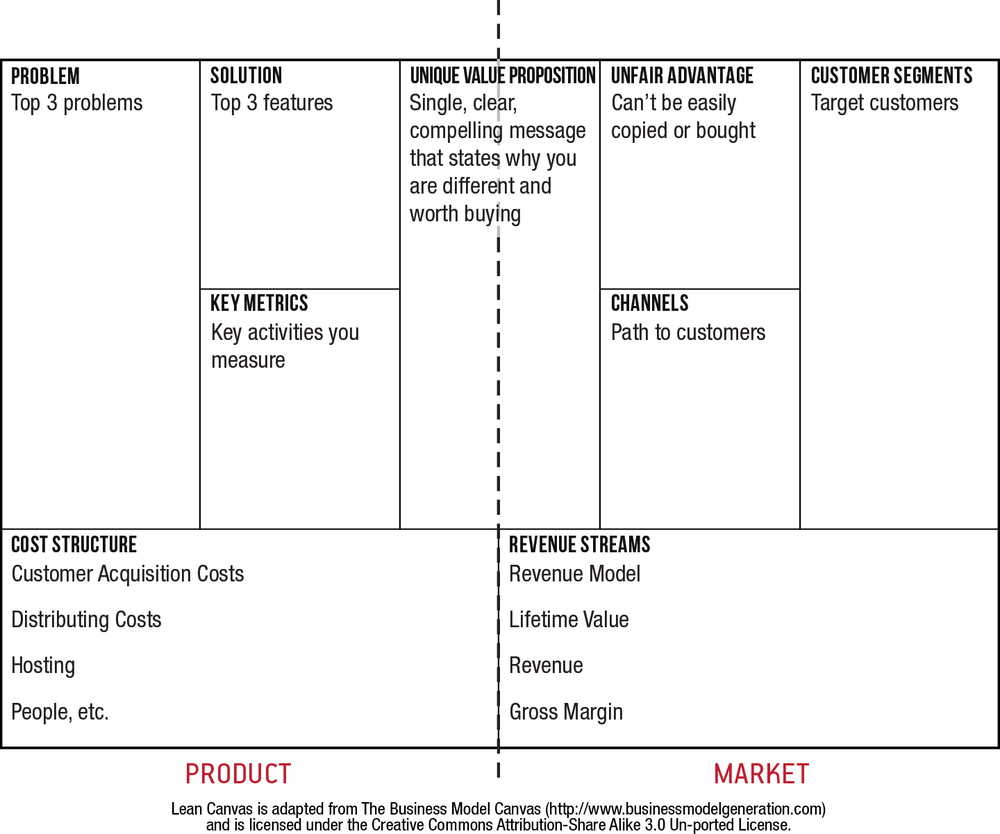

My format of choice is to use the one-page business model diagram (Lean Canvas) shown in Figure 1-1.

Lean Canvas is my adaptation of Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas, which he describes in the book Business Model Generation (Wiley).[4]

I particularly like the one-page canvas format because it is:

- Fast

Compared to writing a business plan, which can take several weeks or months, you can outline multiple business models on a canvas in one afternoon. Because creating these one-page business models takes so little time, I recommend spending a little additional time up front, brainstorming possible variations to your model and then prioritizing where to start.

- Concise

The canvas forces you to pick your words carefully and get to the point. This is great practice for distilling the essence of your product. You have 30 seconds to grab the attention of an investor over a hypothetical elevator ride, and eight seconds to grab the attention of a customer on your landing page.[5]

- Portable

A single-page business model is much easier to share with others, which means it will be read by more people and probably will be more frequently updated.

If you have ever written a business plan or created a slide deck for investors, you’ll immediately recognize most of the building blocks on the canvas. I won’t spend time describing these blocks right now, as we’ll cover them in great detail in Part II of the book.

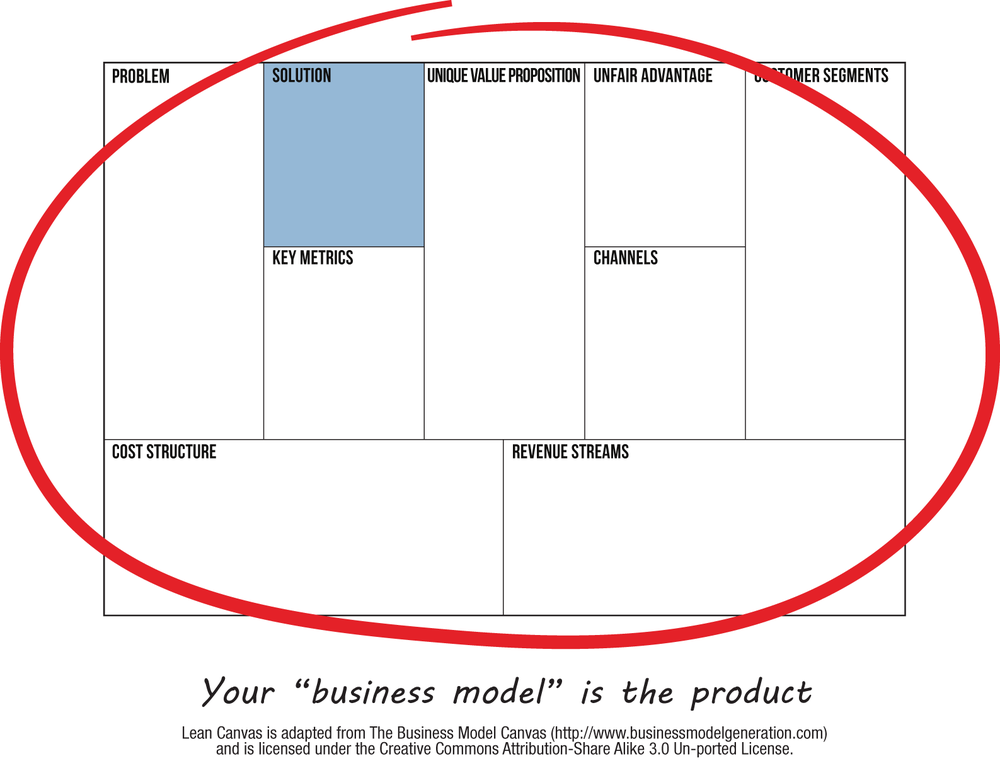

A key point I would like you to take away for now, though, is that your product is NOT “the product” of your startup.

Your Product Is NOT “the Product”

I purposely made the solution box less than one-ninth of the entire canvas because, as entrepreneurs, we are most passionate about the solution box and what we are naturally good at (see Figure 1-2).

Dave McClure of 500 Startups has sat through hundreds of entrepreneur pitches and will probably sit through hundreds more. During these sessions, he has repeatedly called out entrepreneurs for spending a disproportionate amount of time talking about their solution and not enough time talking about the other components of the business model.

Customers don’t care about your solution. They care about their problems.

—Dave McClure, 500 Startups

Investors, and more important, customers, identify with their problems and don’t care about your solution (yet). Entrepreneurs, on the other hand, are naturally wired to look for solutions. But chasing after solutions to problems no one cares enough about is a form of waste.

Your job isn’t just building the best solution, but owning the entire business model and making all the pieces fit.

Recognizing your business model as a product is empowering. Not only does it let you own your business model, but it also allows you to apply well-known techniques from product development to building your company.

If you take a step back, you’ll see that these meta-principles are nothing more than the divide and conquer technique applied to the process of starting up.

Lean Canvas helps deconstruct your business model into nine distinct subparts that are then systematically tested, in order of highest to lowest risk.

Step 2: Identify the Riskiest Parts of Your Plan

Building a successful product is fundamentally about risk mitigation.

Customers buy from you when they trust you can solve their problems. Investors bet on you when they trust you can build a scalable business model.

Startups are a risky business, and our real job as entrepreneurs is to systematically de-risk our startups over time.

Another technique taken from the Product Development playbook is that of “tackling the riskiest parts first.” Not coincidentally, for most products, the solution isn’t what’s riskiest.

Unless you are trying to solve a particularly hard technical problem (like finding a cure for cancer, building the next big search algorithm, or splitting isotopes), chances are you will be able to build your product given enough time, money, and effort.

The bigger risk for most startups is building something nobody wants.

While what’s riskiest varies across products, a lot of that risk is driven by the stage of your startup, which we’ll cover next.

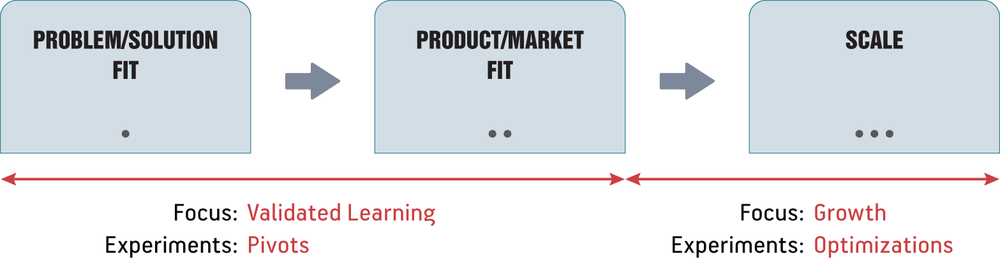

The Three Stages of a Startup

A startup goes through three distinct stages, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Stage 1: Problem/Solution Fit

Key question: Do I have a problem worth solving?

The first stage is about determining whether you have a problem worth solving before investing months or years of effort into building a solution.

While ideas are cheap, acting on them is quite expensive.

A problem worth solving boils down to three questions:

Is it something customers want? (must-have)

Will they pay for it? If not, who will? (viable)

Can it be solved? (feasible)

During this stage, we attempt to answer these questions using a combination of qualitative customer observation and interviewing techniques that we’ll cover in great detail Chapter 5 and Chapter 6.[6]

From there you derive the minimum feature set to address the right set of problems, which is also known as the minimum viable product (MVP).

Stage 2: Product/Market Fit

Key question: Have I built something people want?

Once you have a problem worth solving and your MVP has been built, you then test how well your solution solves the problem. In other words, you measure whether you have built something people want.

In Part IV of this book, we’ll cover both qualitative and quantitative metrics for measuring product/market fit.

Achieving traction or product/market fit is the first significant milestone for a startup. At this stage, you have a plan that is starting to work—you are signing up customers, retaining them, and getting paid.

Stage 3: Scale

Key question: How do I accelerate growth?

After product/market fit, some level of success is almost always guaranteed. Your focus at this stage shifts toward growth, or scaling your business model.

Pivot Before Product/Market Fit, Optimize After

Achieving product/market fit is the first significant milestone of a startup and greatly influences both strategy and tactics. For this reason, it is helpful to further delineate the stages of a startup as “before product/market fit” and “after product/market fit.”

Before product/market fit, the focus of the startup centers on learning and pivots. After product/market fit, the focus shifts toward growth and optimizations. (See Figure 1-4.)

Pivot is a term used by Eric Ries to describe a change in direction of a startup while staying grounded in learning. The best way to differentiate pivots from optimizations is that pivots are about finding a plan that works, while optimizations are about accelerating that plan.

In a pivot experiment, you attempt to validate parts of the business model hypotheses in order to find a plan that works. In an optimization experiment, you attempt to refine parts of the business model hypotheses in order to accelerate a working plan. The goal of the first is a course correction (or a pivot). The goal of the second is efficiency (or scale).

This may sound like a subtle distinction, but it has a significant impact on both strategic and tactical execution. Before product/market fit, a startup needs to be architected to maximize learning.

You stand to learn the most when the probability of the expected outcome is 50%; that is, when you don’t know what to expect.

In order to maximize learning, you have to pick bold outcomes instead of chasing incremental improvements. So, rather than changing the color of your call-to-action button, change your entire landing page. Rather than tweaking your unique value proposition (UVP) for a single customer segment, experiment with different UVPs for different customer segments.

Later in the book, we’ll visit many other examples that explain how you purposely architect for learning over optimization.

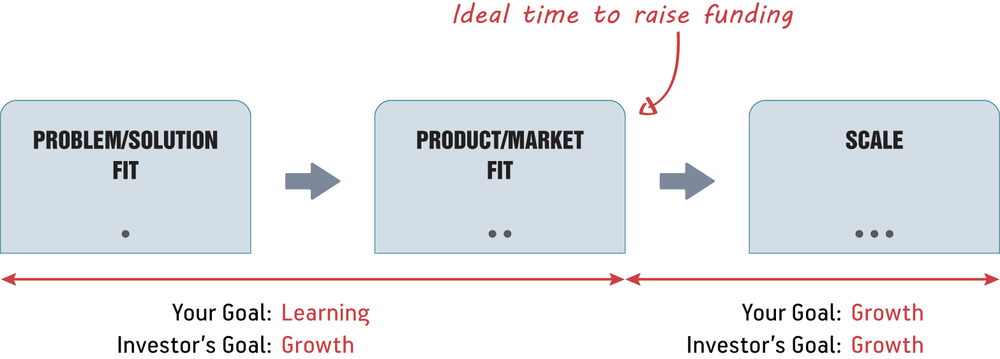

Where Does Funding Fit into All This?

It’s funny to note how the 37signals folks went from “Outside money is Plan B” to “Outside money is Plan Z” between their last two books: Getting Real and Rework (37signals.com). Once you’re profitable, it’s easy to make such a declaration, but some times are certainly better than others to consider external funding (see Figure 1-5).

Even though you may need to raise seed funding sooner, the ideal time to raise your big round of funding is after product/market fit, because at that time, both you and your investors have aligned goals: to scale the business.

Traction is a measure of your product’s engagement with its market. Investors care about traction over everything else.

—Nivi and Naval, Venture Hacks

A lot of (especially first-time) entrepreneurs feel that Step 1 involves writing a business plan/building a slide deck and getting funded. Taking several months to write and pitch a business plan to investors is not the best use of time for a startup; especially since all you have at that point is a vision and a set of untested hypotheses. Selling this to investors without any level of validation is a form of waste.

Instead, your first goal should be to establish just enough of a runway to allow you to start testing and validating your business model with customers.

While not the same thing, bootstrapping and Lean Startups are quite complementary. Both cover techniques for building low-burn startups by eliminating waste through the maximization of existing resources before expending effort on the acquisition of new or external resources.

Bootstrapping + Lean Startup = Low-Burn Startup

(For more, see How to Build a Low-Burn Startup in the Appendix.)

Step 3: Systematically Test Your Plan

With your Plan A documented and your starting risks prioritized, you are now ready to systematically test your plan. In a Lean Startup, this is done by running a series of experiments.

The Lean Startup methodology is strongly rooted in the scientific method, and running experiments is a key activity. We’ll cover steps for running effective experiments in Part III of the book, but for now, let’s start by defining an experiment.

What Is an Experiment?

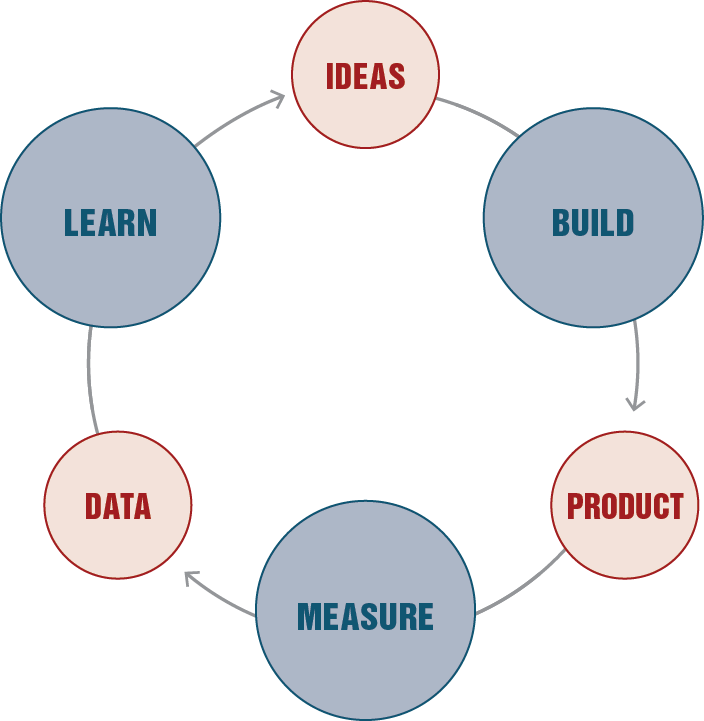

A cycle around the validated learning loop shown in Figure 1-6 is called an experiment.

The validated learning loop, or Build-Measure-Learn loop, was codified by Eric Ries and describes the customer feedback loop that drives learning in a Lean Startup.

It begins in the Build stage with a set of ideas or hypotheses that are used to create some artifact (mock-ups, code, landing page, etc.) for the purpose of testing a hypothesis. We put this artifact in front of customers and “measure” their response using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data. This data is used to derive specific “learning” that serves to validate or refute a hypothesis, which in turn drives the next set of actions.

The Iteration Meta-Pattern

While an experiment helps you validate or invalidate a specific business model hypothesis, an iteration strings multiple experiments together toward achieving a specific goal, such as getting to product/market fit.

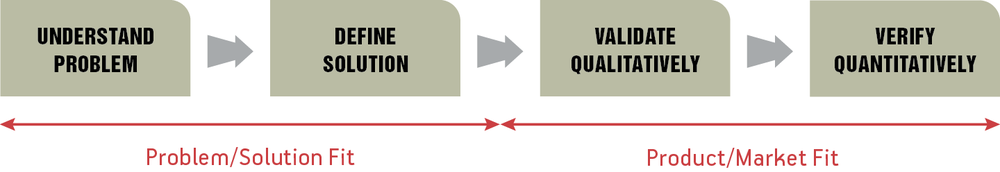

Figure 1-7 shows the basic iteration meta-pattern we’ll use throughout this book.

The first two stages (Understand Problem and Define Solution) are about getting to problem/solution fit or finding a problem worth solving.

Then you iterate toward product/market fit by testing whether you’ve built something people want using a two-stage approach: first qualitative (micro-scale), then quantitative (macro-scale).

[4] To understand the differences between Lean Canvas and the original Business Model Canvas, see http://www.ashmaurya.com/why-lean-canvas.

[5] It is estimated that up to 50% of visitors to landing pages will bail in the first eight seconds. Source: MarketingSherpa’s “Landing Page Handbook” (2005).

[6] In The Four Steps to the Epiphany, Steve Blank points out the importance of in-depth customer interviews, which he terms “Customer Discovery.”

Get Running Lean, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.