Introduction: Why Strategies Fail

Failure is the opportunity to begin again, more intelligently.

Before We Fix It, Let’s Understand Why It Fails

Watching a failed strategy rip through a company is akin to watching a powerful hurricane hit land and devastate everything in its path. Anyone who has witnessed such destruction hopes desperately to never experience such a thing again. When I witnessed it firsthand, I was working inside the third-largest software company in the world, where I managed revenues for the Americas region. I will tell you a story about my most dramtic experience of failed strategy. (Like all the stories in this book, it is a true story, but some identifying details have been changed to respect confidentiality. The exception is “Profile of a Collaborative Leader” in Chapter 3, in which Hans Grande’s real name is used.)

My role had a broad charter to work on product issues, sales compensation plans, marketing, and channel decisions—everything about setting and meeting revenue goals. It gave me a perfect vantage point to watch the events unfold. Unfortunately, I wasn’t an innocent bystander; I was complicit in what went down.

It started innocently enough. My boss stopped by my office, excited, with big news: the company had decided to diversify our product line six-fold within the coming 18 months.

The story she told had all the makings of a legend. The CEO had just shared the results of recent market exploration, which had convinced him that this strategic move would propel the company into the future.

After his inspiring talk, the CEO prompted the VPs to join the rallying cry. The way my boss described it, it was part revival and part campaign stump speech. Apparently, she was the first to volunteer. She said she felt compelled to stand up and assert, “I think we need to do this. Sign the Americas up!”

Even though my boss hadn’t talked to anyone within her organization about what it would take to make this move a reality, she “just knew” it was the right idea to get us to the next level. Besides, she believed that if anyone in the company could figure out how to make this happen, it would be us. After all, we had a stunning track record—always delivered on our revenue, and the team was competent and smart. I distinctly remember being impressed by the leadership my boss was exhibiting.

The vision for this idea was a classic big, hairy, audacious goal. Not just a few products over two to three years, but six new product lines in 18 months. Sales and marketing would generate demand, with new products developed in parallel. A move of this magnitude would touch every facet of our company: revenue forecasts, individuals’ roles, sales efforts, marketing initiatives, product roadmaps, customer expectations, and company reputation. Every part of the company would need to be integrally involved and well coordinated for the whole thing to work. I had concerns, but because I assumed everyone understood the breadth of the impact on the company in the same way I did, I didn’t voice them. After all, who wants to be the one to question a direction, which would seem like tossing a bucket of cold water on the company’s vision?

So I kept quiet, figuring “the leaders” had it under control. Besides, like my boss, I believed in the team. Failure was not an option. Our CEO had said “we must,” and my boss said “we will.” With that in mind, the larger team and I charged forward with every intention to do our best and make good on the vision.

A couple of months into the new revenue cycle, I got a call from a lead product manager who was responsible for the launch of our new product suite. We often talked just to sync up or troubleshoot issues as they came up. This call, however, was different. The voice on the other end of the line was anxious and tense. There was no small talk. No sooner had I said “hello,” than he jumped in and said:

“We have a problem here. You know the lead product? Yeah, the one that’s supposed to net us most of this year’s revenue? We’re not going to be able to ship it with all the features we originally planned.”

That spelled big trouble. If the new product was delayed, our revenue stream would collapse. Orders for our existing products were already getting deferred because the new product direction had been announced. This one piece of news changed everything and set us on the brink of a major sales stall.

There was no question the situation was dire. My boss called a quick meeting with a few key people to ensure we could make decisions quickly. Someone began by framing the facts of the situation to date, and then laid out three options, none of them appealing. We could:

Ship the product without the intended features, then face the analyst and stock market repercussions.

Ship the product with all the features (even though they likely wouldn’t all work) and do a patch release later.

Delay the product for some undetermined amount of time until we could get it right.

The conversation eroded into mayhem. Instead of a thoughtful debate concerning the trade-offs of each difficult option, the meeting quickly became a blame-fest for the Category-5 hurricane blowing its way toward us. The “discussion” included:

“You are responsible for shipping the thing on time.”

“Why did you commit to the deadline if you couldn’t make it?”

“You were never supportive of this plan in the first place.”

“You’re the sales manager. What’s stopping you from delivering revenues from our current product line?”

Everyone in the room was smart and hardworking and absolutely certain that it could not be me who was responsible for this mess. Accusations bred defensiveness, which in turn led to finger-pointing.

Just as quickly as we decided “we must,” it transformed to “we will,” then degenerated into “we can’t,” and we were left wondering “how?”

As you can likely imagine, the team’s frustration rose, filling the room with anger and anxiety. Before the meeting disintegrated completely, someone managed to get traction on the idea that we should simply try to meet those commitments that were in our direct control. We ultimately agreed to ship the product on the original release date, knowing full well that it wouldn’t meet the customer expectations we had previously set.

It doesn’t take a crystal ball to figure out what happened next. There was no deus ex machina, no superhero swooping in to save the day.

Nope. Revenues were weak. Several talented staff members resigned. The sales team was demoralized. The company was mired in the aftermath of key customers buying a product that didn’t work as promised. The company eventually did manage to recover financially, but the corporate culture took a nosedive. In response to the debacle, people adopted cumbersome and complicated procedures to make sure they didn’t get burned again. After taking massive risks with little thought, people sought to avoid risk at all costs. All around, there was a high price to pay for such good intentions.

So what went wrong? How did this well-intentioned new direction turn into such a trainwreck? And who was to blame?

The answer is that none of us, and all of us, were at fault. Despite our best efforts, we were working with a strategy that was doomed from the start because of how it was formed. The market direction and vision of product diversification were solid, but the way that strategy was created itself lacked the deeper organizational engagement necessary to enable the company to achieve business success.

Tip

Despite best efforts, some strategies are doomed from the start because of how they are formed.

We had no process, framework, approach, or set of organizational mechanisms for embracing the direction as it was set forth. And so we didn’t internalize it; we simply took the direction as if that alone were enough. Without a way to consider cross-functional actions, envision different options and their necessary trade-offs, and make some tough choices early on, we missed the things that were essential to ultimate success.

In the absence of both group and individual accountability, it was easy to assume (as I did) that none of us was responsible for overall success or for speaking up whenever something didn’t seem quite right. Since there was no review of options by those who would implement, none of us could recognize the risks of the new vision. Nor was there a way to discover all of the essential small tasks and detailed work we had to complete. Not knowing this, we couldn’t make trade-offs between functional groups. We didn’t know how to form a strategy that would become real. In short, we lacked a way to collaboratively set direction to win.

It was a perfect storm, a tsunami of a strategy failure. And I was left with the lingering questions: why did it happen? And is there another way? I came to learn that yes, there is.

The failure had little, if anything, to do with the rightness of the big idea, and wasn’t really about the abilities of the individuals on our team. The genesis of the storm was the original formation of the strategy itself. We went straight to execution. (As in, do not pass go, do not collect $200 million.) It’s tempting to view the strategy as correct and blame the execution, but that’s off base. A more accurate description of the problem is that the strategy was incomplete.

A fully developed strategy creation process would engage the team, identify the key interdependent tasks that must be done, find the weak spots and make changes, and get buy-in and accountability. All this needs to happen before execution. If we wait until execution, the measures and processes merely drive completion of items on a checklist, not overall clarity of purpose. When we recognize this, it becomes obvious that the thinking and alignment are part of strategy creation. Some might argue that the execution began immediately in this case because of the urgency, but that’s like firing a gun without lining up the sights first. It’s OK if you have a million bullets and don’t mind a few misses. But if you have just one shot, even under time pressure, getting the strategy right must come first (Figure 1).

I’ve shared this tale of woe to give a sense of what a strategy failure looks like. At a glance, the ingredients aren’t any different from those of a strategy success: good intent + good direction or idea + talented people + hard work + “magic black box.” We know there’s magic involved because sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, and we understand as much about the inner workings of that box as we did the magician’s hat at our fifth birthday parties. We need to replace the “magic black box” with a well-understood process framework, or a “New How” to do strategy creation.

Different Types of Strategy Require Different Approaches

After years of working with name-brand organizations and innovative startups, partnering to build successful strategies day in and day out, I’ve come to realize that there is no shared definition of the word “strategy.” Not among exec teams, or boards of directors, or within a single organization, and certainly not across organizations. Each of us uses it to mean something slightly different, and this lack of a shared definition can lead to misunderstandings. So, before we go any further, let me clear up what I mean when I use the word “strategy,” and in particular, what’s included in the scope of the definition as it relates to this notion of collaborative strategy.

Strategies are crucial to competitive organizations. Most people would agree on that, at least. And good strategies are essential to winning companies. So, simply put, a strategy is a way to win. Although it’s seemingly that simple on one level, practitioners know that strategy is also about making choices. It’s about deciding not only what to do but what not to do. And it definitely involves making choices about who to involve, how to listen, which ideas to consider, and how to make tough decisions, as well as knowing what’s most important and why.

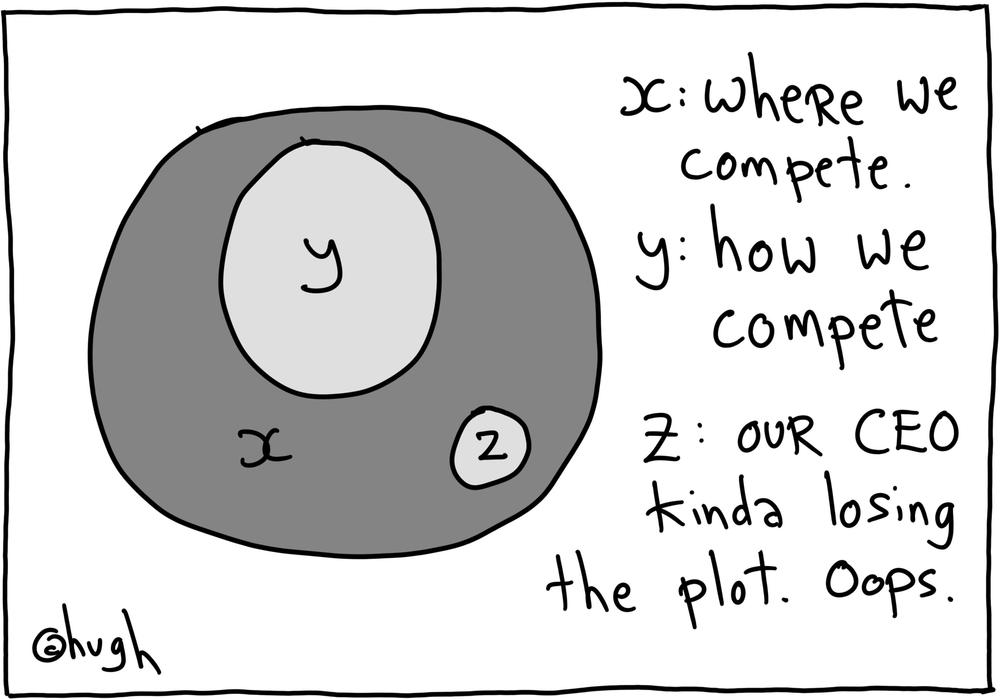

What’s not clear in that definition of strategy is scope, and that’s where confusion often sets in. My own experience and study suggest that strategy falls into two domains. The first (and more known) is the kind of strategy that deals with where we compete, and the second is about how we compete (see Figure 2).

When talking about where we compete, many executives use the word “strategy” to describe what a company should do in 3, 5, or 10 years. Most often, the question the company aims to answer within this domain is which arena or market space they want to win—either in terms of which markets they want to own, or in terms of what positions they want in the larger market value chain. Strategic discussions like this typically take place more or less annually in boardrooms or executive suites. (Although I believe it can benefit the company to encourage good and diverse input on where we compete, the scope of who needs to be involved in making those decisions can be relatively small without affecting the success of that strategy.) A lot of energy has already shaped this big bucket. Many, many great thinkers, particularly Michael Porter, have shaped excellent frameworks on how best to identify the right strategic domain. My intent isn’t to add more to this field of work.

Then there’s the lesser-known second domain: the how we compete strategy. In this case, strategy can be about day-to-day, quarter-toquarter operations, as in: “What strategies would drive 50% growth in our consumer division?” or “What strategy is best to grow sales for Product X?”

In these cases, strategy defines the best ways for us to compete within an arena. This second domain of strategy, while not as “big picture,” has h-u-g-e impact for any organization, because this type of strategy is about determining the best way to win in the chosen space. It can affect which regions, which products, which customer segments, which markets, which product lines, and so on. Once the business domain is set, defining where we want to compete, then nearly every other big decision falls into the domain of “how best to compete.” The effectiveness of this bucket of strategic thinking determines whether the other (larger domain) strategy will turn out to be successful—or not.

The kind of strategy in the “how to compete” domain is the answer to the question, “Given what we want, what is the best way to achieve it?” These are the kinds of strategies that can be created at almost every level of an organization. The more complex and diversified an organization is, the more its people need to excel at this kind of strategy creation. And most companies don’t know—not yet, anyway—how to do that kind of strategy creation in a way that gets the best results. It is this second domain, the strategy of defining how we compete, that is the focus of The New How.

The strategy of “how we compete” is not widely recognized as a form of strategy. Often this domain of strategy is regarded as “tactical” or “execution” or “details,” and so it is not addressed in any coherent way. Alternatively, people have treated the “how” as an extension of the “where,” and they try to apply the tools they already know from Domain #1. Not good. “How we compete” is a domain of strategy that requires its own set of tools, approaches, and frameworks. But they have a hammer, so it must be a nail, and therefore tools of Domain #1 get brought over and used in Domain #2.

This wrestling match over whether the “how” is strategic or tactical, strategy or execution, is actually an unnecessary and fruitless war. Our individual perspectives on the fight are shaped by our positions on the battlefield. From an executive’s viewpoint, the decisions involved in how best to compete look tactical. But to general managers of multibillion-dollar businesses in support of the larger corporation, their decisions don’t seem tactical. And, in my operating view of the world, most “how best to compete” decisions are not tactical. These types of strategies shape and influence the success of the larger company vision.

Tip

One person’s strategy is another’s tactics. The unnecessary and fruitless war of what is tactics or strategy or execution must end.

There is no question in my mind that the “how best to compete” includes both real strategic thinking and a number of tactical decisions. Reflecting back to the opening story, the choice of exactly when to announce the new product direction turned out to be a strategic decision—but it was deemed tactical. Unfortunately, the pervasive idea that the high-level “where” of strategy is all that matters leaves many strategies incomplete. By establishing and maintaining a culture that stuffs the “how” under “execution,” executives unwittingly create a stubborn, persistent structural gap within the organizational entity—one that seriously undermines their ability to succeed.

Perhaps people fixate on execution (“doing what’s required”) instead of finishing up strategy (“choosing the direction”) because it’s easier to see progress during execution than during strategy formation and development.

And who would argue that strategy creation (in either domain) is not hard? Typically, new strategies get initiated first under some form of stress or duress: you need to find a new market for revenue growth, your competition is eating your lunch, or you simply need to get higher performance out of your current product line. In any sufficiently complex organization, it seems that there are millions of things competing in our “day jobs” as we also set direction for the future. Nothing slows down to make it easier to define and make changes while running the existing business.

Taken together, all of these tensions reinforce the organizational and cultural gap between strategy created at the top and execution assigned to the doers of the organization.

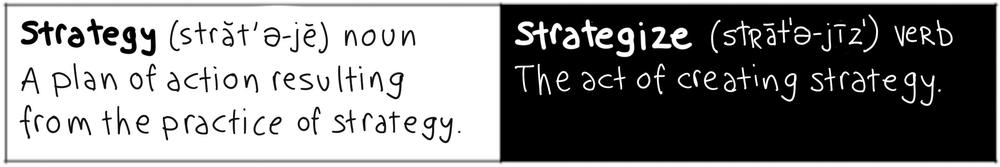

The “How” Matters

This gap exists for a reason. First, most people think of strategy as a plan, a vision, a direction, a thing. They consider that a strategy is the thing that states something like, “Company X will enter the ABC market and own 30% share within five years.” In this way, strategy is a noun, and most of the time, it’s a complicated PowerPoint presentation or a dense three-ring binder filled with research findings and analysis. For all the complexity of slides or density of binders, the “where we should compete” strategy usually can be articulated in a single paragraph or slide. All the other dense information we create in strategy formulation of Domain #1 is background, or justification and “proof.” That is, all that other info helps the “thud” factor and adds credibility, but it rarely helps us take action and make that vision a reality. Those dense wads often cannot and do not guide the execution.

Tip

A strategic direction absolutely needs to be solid for a company to achieve success. But that’s not enough. Yet, it is often treated as if it were all things “strategy” and everything else “execution.” Then all failure is blamed on execution.

When strategy is conceived of as an answer, a noun, a thing, a tool, it’s easy to conclude that all that is needed is the right “thing/idea,” and then strong communication to help the organization understand it. That is, a strategy + a strong orator (or even a demagogue) will enable the organization to succeed. This is especially true when the top executive team sees strategy simply as a vision for the overall organization, and doesn’t understand that the strategy creation process helps align the substrategies that must line up to support the organizational vision and, ultimately, enable the change. The deeper or more complex an organization, the more substrategies need alignment to create a directional move.

Effective strategies are not solely a plan, nor are they complete before implementation begins. A strategy is not just a plan because, although the word “strategy” is by definition a noun (an artifact such as a document or presentation), in practice most people also use the word to refer to the process by which the strategy is created. In other words, people overload the meaning of the word “strategy” because they don’t distinguish the act of creating the way to win—strategizing—from one visible byproduct of the process. By missing this distinction, people are unable to see how much the process of developing the strategy is actually part of the strategy itself.

Tip

Having a great strategic direction or idea without a prepared set of people who “get it” is effectively the same as having a bad idea.

People and their organizations need both the noun/thing form of the strategy and the verb/process of strategy creation (see Figure 3). You may have a wonderful strategy document, but if you begin execution without engaging your team in strategy creation, you have a great-looking PDF and an unprepared set of people. If you engage the team, the PDF may have more typos but the content will be richer, plus there is the less-visible byproduct that your team will be wise, committed, and prepared. This nuance is key: if a strategy is, for our purposes, not complete until it has been put into action to create a new market reality, then the way you create strategy matters a great deal.

When strategy is viewed as a noun and is not accompanied by a robust process framework to enable solid creation, we are left with something that simply won’t work. The thing—the noun—is broken by the very way it was created.

The Air Sandwich

There’s a very specific perspective that leads to creating incomplete, ill-formed (aka “bad”) strategy.

Strategy gets created incompletely mostly because strategy creation is perceived as an elite exercise, something that only an executive group of people can and should do in a hotel ballroom with walls covered in flipchart paper. This worldview becomes evident in a number of ways.

One way in which strategy formation fails is when strategies are entirely set or approved by the executive team. The thinking is that execs are empowered to create strategy, so they hole up in long meetings, using models, complex frameworks, and vast amounts of vetted data to decide things. Although the executives’ intention is to carry the load, the larger organization of talented, experienced, and competent people see the result of that process as an edict from on high.

Another reason execs do strategy alone is that they want to drive alignment, and they believe that having something written down (“cast in stone”) is easier for VPs and managers to communicate consistently. Only a strong organization with a strong high-level vision can tolerate an inclusive definition of the “how.” A weaker effort may have a partial, and therefore flawed, vision that will collapse under the scrutiny of the “how.”

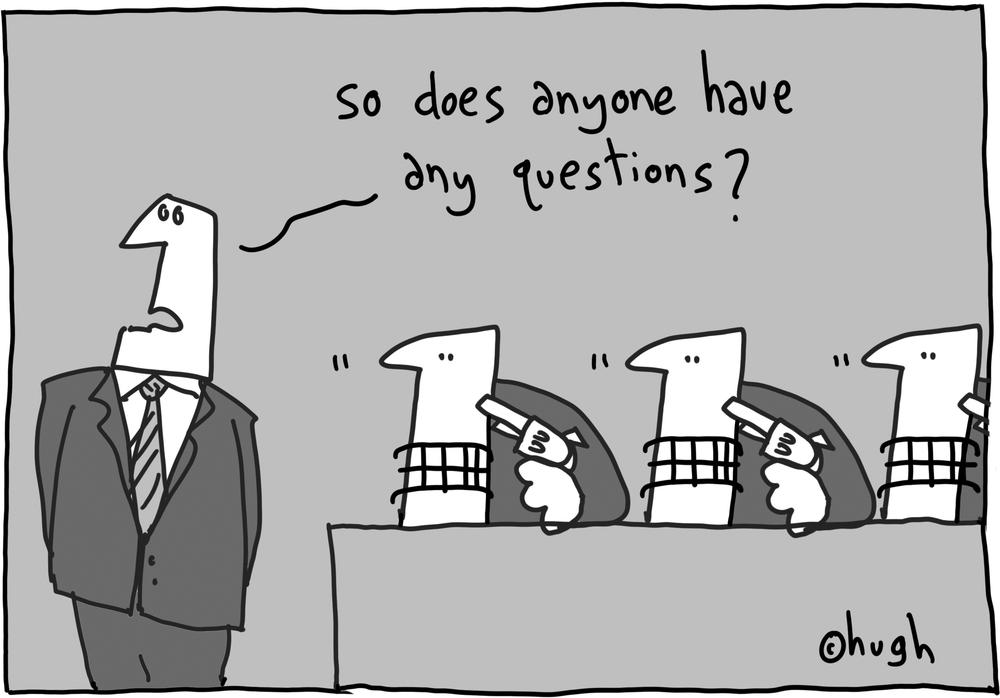

Another way this worldview shows up is in the form of a mild platitude from an operational leader that sounds something like this: “We don’t want to bother you or distract you from your existing work, so we made the strategic decisions for you and want you to validate them in the next 45-minute session of our meeting.” Have you heard things like this from the Powers That Be? If so, did it make you roll your eyes (as soon as you were sure you wouldn’t be seen)? If you’re reading this book, you have an interest in creating successful strategy. You’re not looking to be a bystander in the game of strategy creation.

Those Powers That Be aren’t trying to do something wrong, but they lack a framework or process to do engaged strategy creation well, so they don’t do it at all. Regardless of intent, these examples leave a void in the business. This existing approach to strategy lacks depth and a connection to the realities of the business operations, the needed debate of ideas that result in trade-off discussions, and the need to align capabilities. It lacks a connection to the people who will make that strategy a reality. And it creates an unnecessary separation between the decision of “where to win” and the “how” of winning.

Top-down edicts also typically lack an understanding of organizational capabilities and capacity, as well as an acknowledgment of what the people throughout the organization believe they can accomplish. Obviously, this approach lacks collaboration, debates, discussions, and the necessary engagement of the organization.

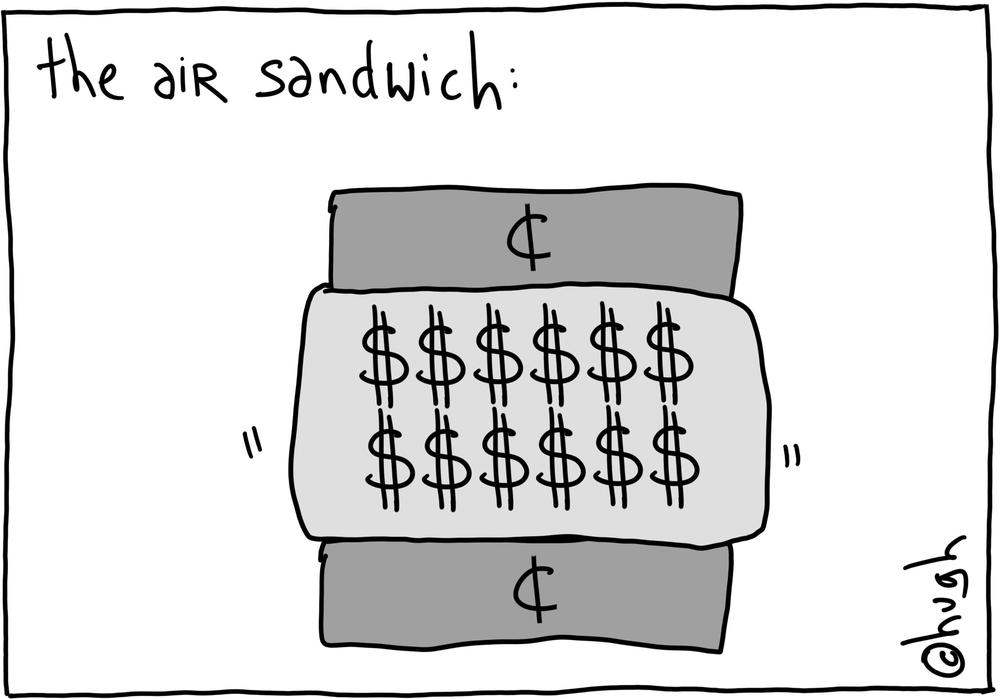

I’ve come to characterize this type of strategy creation as one that guarantees an “Air Sandwich.” This is where the company’s new direction is delivered from an 80,000-foot perspective to the folks holding a 20,000-foot view, who in turn then try to coordinate the people working on the ground—producing a big “Air Sandwich” of strategy (see Figure 4).

An Air Sandwich is, in effect, a strategy that has clear vision and future direction on the top layer, day-to-day action on the bottom, and virtually nothing in the middle—no meaty key decisions that connect the two layers, no rich chewy center filling to align the new direction with new actions within the company.

What is missing in the middle is the substance of the business—the debate of options, the understanding of capabilities, sharing of the underlying assumptions, the identification of risks, issues that need to be tracked, and all the other things that need to be managed. The middle is missing a set of understandings that would connect the vision of the direction to the reality. By focusing only on the top or bottom, we lose the middle, which is where the value is.

When a company has an Air Sandwich, the most valuable details and decisions that enable a strategy to succeed simply are left out of the strategy creation process. And as a result, they are missing from the implementation plans and the execution itself.

In my earlier story, the strategy formation process was clearly incomplete. If we had done it collaboratively, perhaps we could have changed the direction to ship four products in 24 months—not a huge shift but one that would have let the business achieve better results.

For example, when an organization doesn’t test an idea to see whether it’s pragmatic or practical, the organization can unwittingly set itself up for failure. This is the byproduct of assuming a given idea will somehow just work. Or, when a critical underlying assumption isn’t challenged or a risk isn’t highlighted, the people responsible for execution cannot adjust their resource requirements, operating models, or business practices. These disconnects have both direct and indirect costs to the organization (Table 1). Chances are, you could add a couple of items of your own to this table. And for this reason, we need to find a way to change how strategy is created.

|

DISCONNECT |

COST |

|

Data is gathered, but the people with the most insight about the relevance and meaning of that data are not consulted in the interpretation process. |

Decision makers do not have the context to understand the situation clearly and correctly, and therefore they fix the wrong problem or create impractical approaches. |

|

Ideas are generated by a few, but not vetted for organizational implications. |

Creates impractical approaches. Plus, the missed opportunity of gathering perhaps more useful ideas. |

|

An understanding of which practical steps will support the strategy does not exist throughout the organization. |

Different functional groups take different approaches, leading to conflict, frustration, and malaise. Creates an organization of disempowered people. |

|

A misunderstanding between what the top-level executives see in their organization’s future and what the people on the ground know about the capabilities or capacity of the organization. |

Bad decisions are made in the middle levels, causing a diffusion of resources. Money is wasted; time is lost. Employees are alienated. Customers defect. |

|

A commitment to a common cause may exist at the top, but isn’t spread in a tangible way through the organization. |

Tension over issues that appear to be about “wrong people” but often is friction caused by lack of clarity or commitment to the strategy. |

An Air Sandwich may be filled with nothing, but taking a big bite of one can certainly leave a bad taste in your mouth. Some executives who’ve sampled an Air Sandwich in the past will attempt to prevent them in the future by managing at a level of detail that undermines the organization’s leverage, power, and influence. For example, one approach is to circumvent future implementation issues by delivering top-line visions in an almost who-does-what-by-when format. We’ve all heard these kinds of directions given as part of the strategy rollout; they look like this:

“Grow X product in the government space by lowering price.”

“Please include these three requirements in our product specs that Customer X just requested for our next release.”

“Go do a viral video campaign for our PC platform.”

Sounds good, right? Sad to say, it rarely works. Directives like this aim to make it easier to implement a strategy, but this technique of spelling out the ways and means to accomplish a strategic goal is generally a setup for failure. In cases like this, here’s what often happens: the exec team decides not only the goal or direction, as in “Grow X product in the government space,” but they have tacked on the specific way to do it, “by lowering price.”

Again, sounds good. But here’s the rub: what if price isn’t the root cause? Say that the group of people driving government sales at the 20,000-foot level knows for a fact that price is not the issue. Then, essentially, this detailed provisioning of direction becomes a further barrier to success.

The problem here is that the vision itself may be directionally correct, but the details of the directives are incompatible. This mismatch sets up a conflict: which directive is the execution team supposed to follow? Grow product sales in the government space or lower the price? Release the product on schedule as currently designed, or delay the launch until the new features are included? Build a viral video or create something that customers will notice? Should we choose the rock or the hard place?

When the top exec’s strategy doesn’t jive with what employees know to be true, questions stream continuously through people’s minds as internal dialogue:

“Is it just me, or is there a fatal flaw in this strategy?”..."Am I supposed to say something?”..."Will I get in trouble if I say something?”...” Will I get in trouble if I don’t say something?”..."If I talk about my concerns, will I be perceived as a troublemaker?”..."If I can’t see how I can make this happen, will I be told I’m being too tactical?”..."Will I have to pay a price somewhere down the line if I look like I’m not on board with this plan?”

Questions such as “Should I say something?” or “Do they care about my opinion?” are whispered between coworkers when the organization lacks the tools for involving people and supporting collaboration in the strategy creation process (Figure 5).

These kinds of unasked questions are a sure sign that a strategy is headed down the path toward failure, because they signal that the strategy wasn’t created properly or vetted deeply enough in the organization to be executed well.

Offering detailed directives causes special trouble in high change situations, where dynamics in the marketplace cause things to shift quickly. In cases like these, by the time the strategy trickles down through the organizational structure and multiple levels of decision making, the market opportunity may have long disappeared.

Most people become aware of an Air Sandwich in the organization only after the proverbial shit has hit the fan. Messy.

The New How: Let ‘Em Think

The shape and force of outside market pressures will surely impact how a company works to respond. Inside the walls of corporations today, the pressure to continuously improve is relentless. The world of centralized organizations, multi-year product cycles, and one-way communication to our customers and markets is fading fast. All this change brings with it some good news: a more diverse and educated workforce. In 2010, there will be more millennials than baby boomers in the workforce. This new workforce will not only expect to be involved, but they will apply their talents only when they can be fully engaged.

The way strategy creation takes place inside organizations is the key to being able to respond rapidly and fluidly as a whole organization to what’s happening in your marketplace.

Winning depends on fully completed strategy now more than ever before. What leaders at all levels are expected to do today compared to even 10 years ago is amazingly demanding. More and better creative strategies are needed to win, and the rapidly shifting market has robbed us of the luxury we once had to ready, aim, fire. Now, it feels more like fire, fire, fire. This situation is highly demanding of people in a number of ways—begging that they consciously improve their strategy for setting strategy.

There are two ways in which I think about strategy: first, as an organization’s plan for the future, and second, as the act of creating that plan. In short, how you decide is now as important as what you decide. I’ve come to see that the model, framework, theory, or PowerPoint you devise (which is typically how strategy is represented) matters as much as the less-observed set of deliberations, discussions, and understandings that happen amongst people who ask “Can we?” and “Should we?” and “When will we?” It is when the team has these discussions and comes together to say, “Yes, we will...” that an entire organization becomes aligned and can actually go and make the strategy manifest. The key area for improvement is to stop focusing entirely on the PowerPoint, and step up efforts to engage the people. A good friend of mine works for John Chambers, CEO of Cisco Systems, who recently shared the changes he is making to lead in this new business climate:

I was always a command-and-control type. If I said “turn right,” all 65,000 employees turned right.

But it’s not possible for an organization to scale and take on more when only one person is driving all of the strategy. When you’re a command-and-control CEO, individuals impacted by your decision can choose not to buy in, and either slow or even stop the process. This is especially dangerous [in] an industry that moves as fast as this one.

In my view, the days of being vertically integrated and having everything within your control will never return. The entire leadership team, including me, had to invent a different way to operate. It was hard for me at first to be collaborative. When I first got to a meeting, I’d listen for about 10 minutes while the team discussed a problem.

I knew what the answer was, and eventually I’d say, “all right, here’s what we’re going to do.”

But, when I learned to let go and give the team time to come to the right conclusion, I found they made just as good decisions or even better, and just as important, they were more invested in the decision and thus executed it with greater speed and commitment. I had to learn to have the patience to let the group think.[3]

That’s a powerful message. His traditional ways of doing strategy that were successful in the past won’t work in the future. It’s time to take notice. The lesson we can learn from Chambers is that no matter who we are, the way we work and specifically the way we do strategy creation need to be reinvented. We need to let people think and create strategy everywhere. This applies to companies large and small. Smaller companies might find this naturally easier because of their focus, but larger firms have more to gain because of the natural complexity of many businesses, people, directions. Companies that learn to harness the value of decentralized power will win against those that simply exploit their people to perform specific tasks.

Chambers’s words are a call to action for finding ways to let entire organizations think and create, so that what’s created is done better and faster, and is aligned to the larger whole. Chambers tells us that the new approach must share decision-making power, encourage valuable debate, and let the reasoning of “why” something is good be clear and open.

His words suggest that we move from leaders telling and doers doing toward each of us discerning, thinking, and acting. We’ll move from vertical strategy creation (top-down telling) to horizontal strategy creation (where we are all share ownership).

Surely, We Can Do This Important Thing Better

Strategies fail for a number of reasons. Some are legitimate reasons, such as the competition created a better offer or a disruptive opportunity changed the landscape. But there are also pointless reasons why strategies fail—ones that we can change by changing how we do strategy creation.

Many strategy failures are avoidable. Treating strategy as a simple noun or set of ideas—rather than including the necessary verb of strategy creation that makes ideas executable—is a recipe for an Air Sandwich, with all its accompanying misunderstandings, inefficiencies, and improper expectations.

Companies using traditional top-down strategy creation models seem to be going slower and slower. At the same time, the volume and complexity of strategic decisions happening today are increasing. These changing conditions demand a model for thinking about strategy creation and a process framework to guide our thoughts and actions.

Without a way to think about and align strategic decisions, the strategies are doomed to fail. We need a new approach to winning that is not dictated from the highest levels of an organization. Inside the most innovative companies, strategic decisions happen at multiple levels within the organizations. For our businesses to thrive and drive the kind of innovation and growth that our economy needs, we need good strategy creation capabilities throughout our organizations.

We can build a community of people who think about strategy creation not as a set of artifacts, but as a powerful process. Then, together, we can redefine ourselves in how we create value. We can embed collaboration into the system as part of both our thinking and our doing. When we add the talents, perspectives, abilities, and desires of the organization into the process, we can make strategy creation an ongoing process of creative collaboration.

Let’s move forward and focus on a more predictable and consistent approach to strategy creation: one that combines strategy and execution, engages people in collaboration, and takes into account the essential conditions that are necessary for well-formed strategies to happen.

The first step is to recognize the structural barriers that drive faulty processes. Let go of the idea that when strategy fails, someone—a human being—must be at fault, and not the established system itself. We’re smarter than that! Consider the faulty assumptions and rules and the resulting processes. The very way we go about creating strategy determines a big share of its success downstream. To fix the outcome of strategy, we need to look at the total system that produces strategy. That’s next.

Get The New How now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.