Personalization

Now that you’ve been introduced to the default desktop and have a good feel for where everything is, what it does, and how it works, you may wish to customize it to your own preferences—and personalization is something at which Ubuntu excels, due to its tremendous range of customization options and preference settings.

Appearance

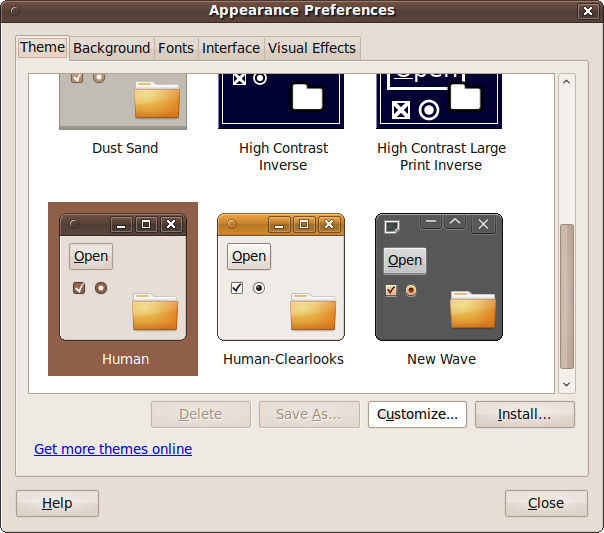

The place to start when customizing Ubuntu is the Appearance Preferences window, which you get to by selecting System → Preferences → Appearance. As Figure 4-30 shows, there are five main sections divided into tabs.

Figure 4-30. The Appearance Preferences window

Theme

The Theme tab lets you choose between a selection of predefined themes, of which Human is the default. Try clicking different ones, and the desktop will change after a few seconds. For example, a good theme to choose for people with visual difficulties would be High Contrast Large Print Inverse. Whichever theme you choose will stay selected.

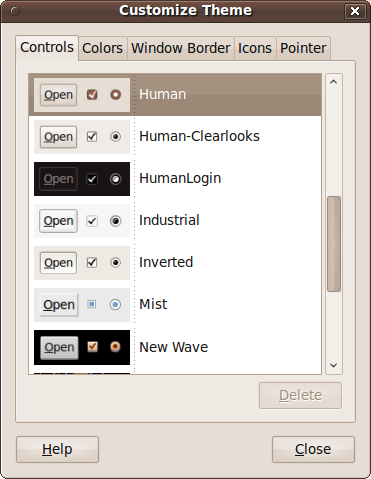

You can further modify a theme by clicking the Customize button, which brings up another window with five options (see Figure 4-31).

Figure 4-31. The Customize Theme window

- Controls

Lets you choose how you want items such as checkboxes and buttons to appear. Just click the example you want to use.

- Colors

Lets you choose the text and background colors ...