A shortcut is a link to a file, folder, disk, or program (see Figure 4-10). You might think of it as a duplicate of the thing’s icon—but not a duplicate of the thing itself. (A shortcut takes up almost no disk space.) When you double-click the shortcut icon, the original folder, disk, program, or document opens. You can also set up a keystroke for a shortcut icon, so that you can open any program or document just by pressing a certain key combination.

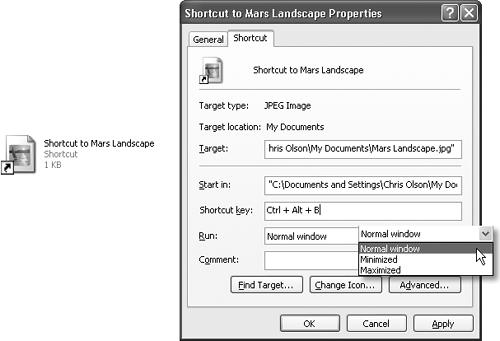

Figure 4-10. You can distinguish a desktop shortcut (left) from its original in two ways. First, the tiny arrow “badge” identifies it as a shortcut. Second, its name contains the word shortcut (unless you’ve renamed it or an application has created its own shortcut on the desktop). The Properties dialog box for a shortcut (right) indicates which actual file or folder this one “points” to. The Run drop-down menu lets you control how the window opens when you double-click the shortcut icon.

Shortcuts provide quick access to the items you use most often. And because you can make as many shortcuts of a file as you want, and put them anywhere on your PC, you can effectively keep an important program or document in more than one folder. Just create a shortcut of each to leave on the desktop in plain sight, or drag their icons onto the Start button or the Quick Launch toolbar. In fact, everything listed in the Start→Programs menu is a shortcut—even the My Documents folder on the desktop is a shortcut (to the actual My Documents folder).

Tip

Don’t confuse the term shortcut, which refers to one of these duplicate-icon pointers, with shortcut menu, the context-sensitive menu that appears when you right-click almost anything in Windows. The shortcut menu has nothing to do with the shortcut icons feature. Maybe that’s why it’s sometimes called the context menu.

To create a shortcut, right-drag an icon from its current location (Windows Explorer, a folder window, or even the Search window described in Section 2.8) to the desktop. When you release the mouse button, choose Create Shortcut(s) Here from the menu that appears.

Tip

If you’re not in the mood for using a shortcut menu, just left-drag an icon while pressing Alt. A shortcut appears instantly. (And if your keyboard lacks an Alt key—yeah, right—drag while pressing Ctrl+Shift instead.)

You can delete a shortcut the same as any icon, as described in the Recycle Bin discussion earlier in this chapter. (Of course, deleting a shortcut doesn’t delete the file it points to.)

To locate the original icon (program, folder, document, or whatever) from which a shortcut was made, right-click the shortcut icon and choose Properties from the shortcut menu. As shown in Figure 4-10, the resulting box shows you where to find the “real” icon—and offers you a quick way to jump to it, in the form of the Find Target button. When you click Find Target, you jump to the folder that stores the icon, which shows up highlighted.

Even after reading all of this gushing prose about the virtues of shortcuts, efficiency experts may still remain skeptical. Sure, shortcuts let you put favored icons everywhere you want to be, such as your Start menu, Quick Launch toolbar, the desktop, and so on. But they still require clicking to open, which means taking your hands off the keyboard—and that, in the grand scheme of things, means slowing down.

Lurking within the Shortcut Properties dialog box is another feature with intriguing ramifications: the Shortcut Key text box. By clicking here and then pressing a key combination, you can assign a personalized keystroke for the shortcut. Thereafter, by pressing that keystroke, you can summon the corresponding file, program, folder, printer, networked computer, or disk window to your screen (no matter what you’re doing on the PC).

Three rules apply when choosing keystrokes to open your favorite icons:

The keystrokes work only on shortcuts stored on your desktop or in the Start menu. If you stash the icon in any other folder, the keystroke stops working.

Your keystroke can’t incorporate the Space bar or the Backspace, Delete, Esc, Print Screen, or Tab keys.

There are no one- or two-key combinations available here. Your combination must include at least two of these three keys—Ctrl, Shift, and Alt—and another key.

Windows XP enforces this rule rigidly. For example, if you type a single letter key into the box (like E), Windows automatically adds the Ctrl and Alt keys to your combination (Ctrl+Alt+E). All of this is the operating system’s attempt to prevent you from inadvertently duplicating one of the built-in Windows keyboard shortcuts and thoroughly confusing both your computer and yourself.

Tip

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be a programmer, try this. In the Shortcut Properties dialog box (Figure 4-10), use the Run drop-down menu at the bottom of the dialog box to choose Normal window, Minimized, or Maximized. By clicking OK, you’ve just told Windows what kind of window you want to appear when opening this particular shortcut. (See Section 3.1 for a discussion of these window types.)

OK, controlling your Windows in this way isn’t exactly the same as programming Microsoft Access, but you are, in your own small way, telling Windows what to do.

Get Windows XP Professional: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.