Often in video games, nonplayer characters must move in cohesive groups rather than independently. Let’s consider some examples. Say you’re writing an online role-playing game, and just outside the main town is a meadow of sheep. Your sheep would appear more realistic if they were grazing in a flock rather than walking around aimlessly. Perhaps in this same role-playing game is a flock of birds that prey on the game’s human inhabitants. Here again, birds that hunt in flocks rather than independently would seem more realistic and pose the challenge to the player of dealing with somewhat cooperating groups of predators. It’s not a huge leap of faith to see that you could apply such flocking behavior to giant ants, bees, rats, or sea creatures as well.

These examples of local fauna moving, grazing, or attacking in herds or flocks might seem like obvious ways in which you can use flocking behavior in games. With that said, you do not need to limit such flocking behavior to fauna and can, in fact, extend it to other nonplayer characters. For example, in a real-time strategy simulation, you can use group movement behavior for nonplayer unit movement. These units can be computer-controlled humans, trolls, orcs, or mechanized vehicles of all sorts. In a combat flight simulation, you can apply such group movement to computer-controlled squadrons of aircraft. In a first-person shooter, computer-controlled enemy or friendly squads can employ such group movement. You even can use variations on basic flocking behavior to simulate crowds of people loitering around a town square, for example.

In all these examples, the idea is to have the nonplayer characters move cohesively with the illusion of having purpose. This is as opposed to a bunch of units that move about, each with their own agenda and with no semblance of coordinated group movement whatsoever.

At the heart of such group behavior lie basic flocking algorithms such as the one presented by Craig Reynolds in his 1987 SIGGRAPH paper, “Flocks, Herds, and Schools: A Distributed Behavioral Model.” You can apply the algorithm Reynolds presented in its original form to simulate flocks of birds, fish, or other creatures, or in modified versions to simulate group movement of units, squads, or air squadrons. In this chapter we’re going to take a close look at a basic flocking algorithm and show how you can modify it to handle such situations as obstacle avoidance. For generality, we’ll use the term units to refer to the individual entities comprising the group—for example, birds, sheep, aircraft, humans, and so on—throughout the remainder of this chapter.

Craig Reynolds coined the term boids when referring to his simulated flocks. The behavior he generated very closely resembles shoals of fish or flocks of birds. All the boids can be moving in one direction at one moment, and then the next moment the tip of the flock formation can turn and the rest of the flock will follow as a wave of turning boids propagates through the flock. Reynolds’ implementation is leaderless in that no one boid actually leads the flock; in a sense they all sort of follow the group, which seems to have a mind of its own. The motion Reynolds’ flocking algorithm generated is quite impressive. Even more impressive is the fact that this behavior is the result of three elegantly simple rules. These rules are summarized as follows:

- Cohesion

Have each unit steer toward the average position of its neighbors.

- Alignment

Have each unit steer so as to align itself to the average heading of its neighbors.

- Separation

Have each unit steer to avoid hitting its neighbors.

It’s clear from these three rule statements that each unit must be able to steer, for example, by application of steering forces. Further, each unit must be aware of its local surroundings—it has to know where its neighbors are located, where they’re headed, and how close they are to it.

In physically simulated, continuous environments, you can steer by applying steering forces on the units being simulated. Here you can apply the same technique we used in the chasing, evading, and pattern movement examples earlier in the book. (Refer to Chapter 2 and, specifically, to Figure 2-7 and surrounding discussion to see how you can handle steering.) We should point out that many flocking algorithms you’ll find in other printed material or on the Web use particles to represent the units, whereas here we’re going to use rigid bodies such as those we covered in Chapters 2 and 3. Although particles are easier to handle in that you don’t have to worry about rotation, it’s very likely that in your games the units won’t be particles. Instead, they’ll be units with a definite volume and a well defined front and back, which makes it important to track their orientations so that while moving around, they rotate to face the direction in which they are heading. Treating the units as rigid bodies enables you to take care of orientation.

For tiled environments, you can employ the line-of-sight methods we used in the tile-based chasing and evading examples to have the units steer, or rather, head toward a specific point. For example, in the case of the cohesion rule, you’d have the unit head toward the average location, expressed as a tile coordinate, of its neighbors. (Refer to the section “Line-of-Sight Chasing” in Chapter 2.)

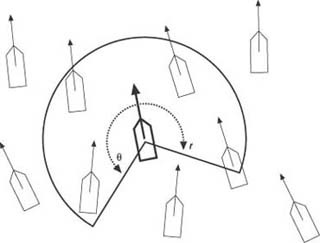

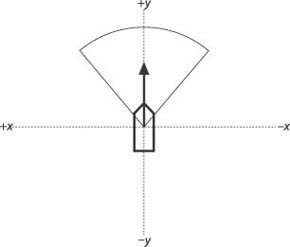

To what extent is each unit aware of its neighbors? Basically, each unit is aware of its local surroundings—that is, it knows the average location, heading, and separation between it and the other units in the group in its immediate vicinity. The unit does not necessarily know what the entire group is doing at any given time. Figure 4-1 illustrates a unit’s local visibility.

Figure 4-1 illustrates a unit (the bold one in the middle of the figure) with a visibility arc of radius r around it. The unit can see all other units that fall within that arc. The visible units are used when applying the flocking rules; all the other units are ignored. The visibility arc is defined by two parameters—the arc radius, r, and the angle, θ. Both parameters affect the resulting flocking motion, and you can tune them to your needs.

In general, a large radius will allow the unit to see more of the group, which results in a more cohesive flock. That is, the flock tends to splinter into smaller flocks less often because each unit can see where most or all of the units are and steer accordingly. On the other hand, a smaller radius tends to increase the likelihood of the flock to splinter, forming smaller flocks. A flock might splinter if some units temporarily lose sight of their neighbors, which can be their link to the larger flock. When this occurs, the detached units will splinter off into a smaller flock and could perhaps rejoin the others if they happen to come within sight again. Navigating around obstacles also can cause a flock to break up. In this case, a larger radius will help the flock to rejoin the group.

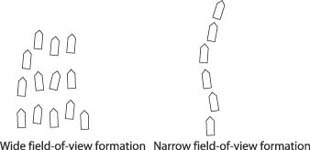

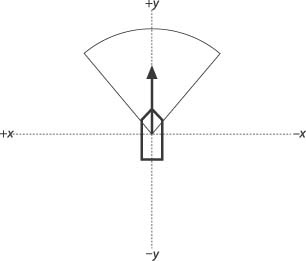

The other parameter, θ, measures the field of view, so to speak, of each unit. The widest field of view is, of course, 360 degrees. Some flocking algorithms use a 360-degree field of view because it is easier to implement; however, the resulting flocking behavior might be somewhat unrealistic. A more common field of view is similar to that illustrated in Figure 4-1, where there is a distinct blind spot behind each unit. Here, again, you can tune this parameter to your liking. In general, a wide field of view, such as the one illustrated in Figure 4-2 in which the view angle is approximately 270 degrees, results in well formed flocks. A narrow field of view, such as the one illustrated in Figure 4-2 in which the view angle is a narrow 45 degrees, results in flocks that tend to look more like a line of ants walking along a path.

Both results have their uses. For example, if you were simulating a squadron of fighter jets, you might use a wide field of view. If you were simulating a squad of army units sneaking up on someone, you might use a narrow field of view so that they follow each other in a line and, therefore, do not present a wide target as they make their approach. If you combine this latter case with obstacle avoidance, your units would appear to follow the point man as they sneak around obstacles.

Later, we’ll build on the three flocking rules of cohesion, alignment, and separation to facilitate obstacle avoidance and leaders. But first, let’s go through some example code that implements these three rules.

The example we’re going to look at involves simulating several units in a continuous environment. Here, we’ll use the same rigid-body simulation algorithms we used in the chasing and pattern movement examples we discussed earlier. This example is named AIDemo4, and it’s available for download from the book’s Web site (http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/ai).

Basically, we’re going to simulate about 20 units that will move around in flocks and interact with the environment and with a player. For this simple demonstration, interaction with the environment consists of avoiding circular objects. The flocking units interact with the player by chasing him.

For this example, we’ll implement a steering model that is more or less identical to the one we used in the physics-based demo in Chapter 2. You can refer to Figure 2-8 and the surrounding discussion to refresh your memory on the steering model. Basically, we’re going to treat each unit as a rigid body and apply a net steering force at the front end of the unit. This net steering force will point in either the starboard or port direction relative to the unit and will be the accumulation of steering forces determined by application of each flocking rule. This approach enables us to implement any number or combination of flocking rules—each rule makes a small contribution to the total steering force and the net result is applied to the unit once all the rules are considered.

We should caution you that this approach does require some tuning to make sure no single rule dominates. That is, you don’t want the steering force contribution from a given rule to be so strong that it always overpowers the contributions from other rules. For example, if we make the steering force contribution from the cohesion rule overpower the others, and say we implement an obstacle avoidance rule so that units try to steer away from objects, if the cohesion rule dominates, the units might stay together. Therefore, they will be unable to steer around objects and might run into or through them. To mitigate this sort of unbalance, we’re going to do two things: first, we’re going to modulate the steering force contribution from each rule; and second, we’re going to tune the steering model to make sure everything is balanced, at least most of the time.

Tuning will require trial and error. Modulating the steering forces will require that we write the steering force contribution from each rule in the form of an equation or response curve so that the contribution is not constant. Instead, we want the steering force to be a function of some key parameter important to the given rule.

Consider the avoidance rule for a moment. In this case, we’re trying to prevent the units from running into each other, while at the same time enabling the units to get close to each other based on the alignment and cohesion rules. We want the avoidance rule steering force contribution to be small when the units are far away from each other, but we want the avoidance rule steering force contribution to be relatively large when the units are dangerously close to each other. This way, when the units are far apart, the cohesion rule can work to get them together and form a flock without having to fight the avoidance rule. Further, once the units are in a flock, we want the avoidance rule to be strong enough to prevent the units from colliding in spite of their tendency to want to stay together due to the cohesion and alignment rules. It’s clear in this example that separation distance between units is an important parameter. Therefore, we want to write the avoidance steering force as a function of separation distance. You can use an infinite number of functions to accomplish this task; however, in our experience, a simple inverse function works fine. In this case, the avoidance steering force is inversely proportional to the separation distance. Therefore, large separation distances yield small avoidance steering forces, while small separation distances yield larger avoidance steering forces.

We’ll use a similar approach for the other rules. For example, for alignment we’ll consider the angle between a given unit’s current heading relative to the average heading of its neighbors. If that angle is small, we want to make only a small adjustment to its heading, whereas if the angle is large, a larger adjustment is required. To achieve such behavior, we’ll make the alignment steering force contribution directly proportional to the angle between the unit’s current heading and the average heading of its neighbors. In the following sections, we’ll look at and discuss some code that implements this steering model.

As we discussed earlier, each unit in a flock must be aware of its neighbors. Exactly how many neighbors each unit is aware of is a function of the field-of-view and view radius parameters shown in Figure 4-1. Because the arrangement of the units in a flock will change constantly, each unit must update its view of the world each time through the game loop. This means we must cycle through all the units in the flock collecting the required data. Note that we have to do this for each unit to acquire each unit’s unique perspective. This neighbor search can become computationally expensive as the number of units grows large. The sample code we discuss shortly is written for clarity and is a good place to make some optimizations.

The example program entitled AIDemo4, which you can download from the book’s web site (http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/ai), is set up similar to the examples we discussed earlier in this book. In this example, you’ll find a function called UpdateSimulation that is called each time through the game, or simulation, loop. This function is responsible for updating the positions of each unit and for drawing each unit to the display buffer. Example 4-1 shows the UpdateSimulation function for this example.

Example 4-1. UpdateSimulation function

void UpdateSimulation(void)

{

double dt = _TIMESTEP;

int i;

// Initialize the back buffer:

if(FrameCounter >= _RENDER_FRAME_COUNT)

{

ClearBackBuffer();

DrawObstacles();

}

// Update the player-controlled unit (Units[0]):

Units[0].SetThrusters(false, false, 1);

if (IsKeyDown(VK_RIGHT))

Units[0].SetThrusters(true, false, 0.5);

if (IsKeyDown(VK_LEFT))

Units[0].SetThrusters(false, true, 0.5);

Units[0].UpdateBodyEuler(dt);

if(Units[0].vPosition.x > _WINWIDTH) Units[0].vPosition.x = 0;

if(Units[0].vPosition.x < 0) Units[0].vPosition.x = _WINWIDTH;

if(Units[0].vPosition.y > _WINHEIGHT) Units[0].vPosition.y = 0;

if(Units[0].vPosition.y < 0) Units[0].vPosition.y = _WINHEIGHT;

if(FrameCounter >= _RENDER_FRAME_COUNT)

DrawCraft(Units[0], RGB(0, 255, 0));

// Update the computer-controlled units:

for(i=1; i<_MAX_NUM_UNITS; i++)

{

DoUnitAI(i);

Units[i].UpdateBodyEuler(dt);

if(Units[i].vPosition.x > _WINWIDTH)

Units[i].vPosition.x = 0;

if(Units[i].vPosition.x < 0)

Units[i].vPosition.x = _WINWIDTH;

if(Units[i].vPosition.y > _WINHEIGHT)

Units[i].vPosition.y = 0;

if(Units[i].vPosition.y < 0)

Units[i].vPosition.y = _WINHEIGHT;

if(FrameCounter >= _RENDER_FRAME_COUNT)

{

if(Units[i].Leader)

DrawCraft(Units[i], RGB(255,0,0));

else {

if(Units[i].Interceptor)

DrawCraft(Units[i], RGB(255,0,255));

else

DrawCraft(Units[i], RGB(0,0,255));

}

}

}

// Copy the back buffer to the screen:

if(FrameCounter >= _RENDER_FRAME_COUNT) {

CopyBackBufferToWindow();

FrameCounter = 0;

} else

FrameCounter++;

}UpdateSimulation performs the usual tasks. It clears the back buffer upon which the scene will be drawn; it handles any user interaction for the player-controlled unit; it updates the computer-controlled units; it draws everything to the back buffer; and it copies the back buffer to the screen when done. The interesting part for our purposes is where the computer-controlled units are updated. For this task, UpdateSimulation loops through an array of computer-controlled units and, for each one, calls another function named DoUnitAI. All the fun happens in DoUnitAI, so we’ll spend the remainder of this chapter looking at this function.

DoUnitAI handles everything with regard to the computer-controlled unit’s movement. All the flocking rules are implemented in this function. Before the rules are implemented, however, the function has to collect data on the given unit’s neighbors. Notice here that the given unit, the one currently under consideration, is passed in as a parameter. More specifically, an array index to the current unit under consideration is passed in to DoUnitAI as the parameter i.

Example 4-2 shows a snippet of the very beginning of DoUnitAI. This snippet contains only the local variable list and initialization code. Normally, we just brush over this kind of code, but because this code contains a relatively large number of local variables and because they are used often in the flocking calculations, it’s worthwhile to go through it and state exactly what each one represents.

Example 4-2. DoUnitAI initialization

void DoUnitAI(int i)

{

int j;

int N; // Number of neighbors

Vector Pave; // Average position vector

Vector Vave; // Average velocity vector

Vector Fs; // Net steering force

Vector Pfs; // Point of application of Fs

Vector d, u, v, w;

double m;

bool InView;

bool DoFlock = WideView||LimitedView||NarrowView;

int RadiusFactor;

// Initialize:

Fs.x = Fs.y = Fs.z = 0;

Pave.x = Pave.y = Pave.z = 0;

Vave.x = Vave.y = Vave.z = 0;

N = 0;

Pfs.x = 0;

Pfs.y = Units[i].fLength / 2.0f;

.

.

.

}We’ve already mentioned that the parameter, i, represents the array index to the unit currently under consideration. This is the unit for which all the neighbor data will be collected and the flocking rules will be implemented. The variable, j, is used as the array index to all other units in the Units array. These are the potential neighbors to Units[i]. N represents the number of neighbors that are within view of the unit currently under consideration. Pave and Vave will hold the average position and velocity vectors, respectively, of the N neighbors. Fs represents the net steering force to be applied to the unit under consideration. Pfs represents the location in body-fixed coordinates at which the steering force will be applied. d, u, v, and w are used to store various vector quantities that are calculated throughout the function. Such quantities include relative position vectors and heading vectors in both global and local coordinates. m is a multiplier variable that always will be either +1 or −1. It’s used to make the steering forces point in the directions we need—that is, to either the starboard or port side of the unit under consideration. InView is a flag that indicates whether a particular unit is within view of the unit under consideration. DoFlock is simply a flag that indicates whether to apply the flocking rules. In this demo, you can turn flocking on or off. Further, you can implement three different visibility models to see how the flock behaves. These visibility models are called WideView, LimitedView, and NarrowView. Finally, RadiusFactor represents the r parameter shown in Figure 4-1, which is different for each visibility model. Note the field-of-view angle is different for each model as well; we’ll talk more about this in a moment.

After all the local variables are declared, several of them are initialized explicitly. As you can see in Example 4-2, they are, for the most part, initialized to 0. The variables you see listed there are the ones that are used to accumulate some value—for example, to accumulate the steering force contributions from each rule, or to accumulate the number of neighbors within view, and so on. The only one not initialized to 0 is the vector Pfs, which represents the point of application of the steering force vector on the unit under consideration. Here, Pfs is set to represent a point on the very front and centerline of the unit. This will make the steering force line of action offset from the unit’s center of gravity so that when the steering force is applied, the unit will move in the appropriate direction as well as turn and face the appropriate direction.

Upon completing the initialization of local variables, DoUnitAI enters a loop to gather information about the current unit’s neighbors, if there are any.

Example 4-3 contains a snippet from DoUnitAI that performs all the neighbor checks and data collection. To this end, a loop is entered, the j loop, whereby each unit in the Units array—except for Units[0] (the player-controlled unit) and Units[i] (the unit for which neighbors are being sought)—is tested to see if it is within view of the current unit. If it is, its data is collected.

Example 4-3. Neighbors

.

.

.

for(j=1; j<_MAX_NUM_UNITS; j++)

{

if(i!=j)

{

InView = false;

d = Units[j].vPosition - Units[i].vPosition;

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, d);

if(WideView)

{

InView = ((w.y > 0) || ((w.y < 0) &&

(fabs(w.x) >

fabs(w.y)*

_BACK_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _WIDEVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(LimitedView)

{

InView = (w.y > 0);

RadiusFactor = _LIMITEDVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(NarrowView)

{

InView = (((w.y > 0) && (fabs(w.x) <

fabs(w.y)*

_FRONT_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _NARROWVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(InView)

{

if(d.Magnitude() <= (Units[i].fLength *

RadiusFactor))

{

Pave += Units[j].vPosition;

Vave += Units[j].vVelocity;

N++;

}

}

.

.

.

}

}

.

.

.After checking to make sure that i is not equal to j—that is, we aren’t checking the current unit against itself—the function calculates the distance vector between the current unit, Units[i], and Units[j], which is simply the difference in their position vectors. This result is stored in the local variable, d. Next, d is converted from global coordinates to local coordinates fixed to Units[i]. The result is stored in the vector w.

Next, the function goes on to check to see if Units[j] is within the field of view of Units[i]. This check is a function of the field-of-view angle as illustrated in Figure 4-1; we’ll check the radius value later, and only if the field-of-view check passes.

Now, because this example includes three different visibility models, three blocks of code perform field-of-view checks. These checks correspond to the wide-field-of-view, the limited-field-of-view, and the narrow-field-of-view models. As we discussed earlier, a unit’s visibility influences the group’s flocking behavior. You can toggle each model on or off in the example program to see their effect.

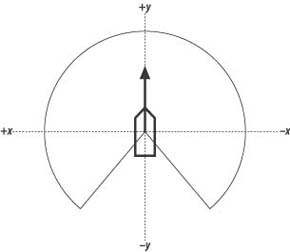

The wide-view model offers the greatest visibility and lends itself to easily formed and regrouped flocks. In this case, each unit can see directly in front of itself, to its sides, and behind itself, with the exception of a narrow blind spot directly behind itself. Figure 4-3 illustrates this field of view.

The test to determine whether Units[j] falls within this field of view consists of two parts. First, if the relative position of Units[j] in terms of local coordinates fixed to the current unit, Units[i], is such that its y-coordinate is positive, we know that Units[j] is within the field of view. Second, if the y-coordinate is negative, it could be either within the field of view or in the blind spot, so another check is required. This check looks at the x-coordinate to determine if Units[j] is located within the pie slice-shaped blind spot formed by the two straight lines that bound the visibility arc, as shown in Figure 4-3. If the absolute value of the x-coordinate of Units[j] is greater than some factor times the absolute value of the y-coordinate, we know Units[j] is located on the outside of the blind spot—that is, within the field of view. That factor times the absolute value of the y-coordinate calculation simply represents the straight lines bounding the field-of-view arc we mentioned earlier. The code that performs this check is shown in Example 4-3, but the key part is repeated here in Example 4-4 for convenience.

Example 4-4. Wide-field-of-view check

.

.

.

if(WideView)

{

InView = ((w.y > 0) || ((w.y < 0) &&

(fabs(w.x) >

fabs(w.y)*

_BACK_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _WIDEVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

.

.

.In the code shown here, the BACK_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR represents a field-of-view angle factor. If it is set to a value of 1, the field-of-view bounding lines will be 45 degrees from the x-axis. If the factor is greater than 1, the lines will be closer to the x-axis, essentially creating a larger blind spot. Conversely, if the factor is less than 1, the lines will be closer to the y-axis, creating a smaller blind spot.

You’ll also notice here that the RadiusFactor is set to some predefined value, _WIDEVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR. This factor controls the radius parameter shown in Figure 4-1. By the way, when tuning this example, this radius factor is one of the parameters that require adjustment to achieve the desired behavior.

The other two visibility model checks are very similar to the wide-view model; however, they each represent smaller and smaller fields of view. These two models are illustrated in Figures 4-4 and 4-5.

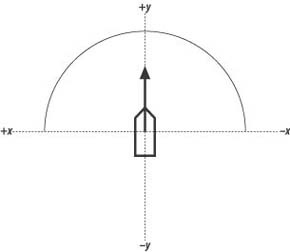

In the limited-view model, the visibility arc is restricted to the local positive y-axis of the unit. This means each unit cannot see anything behind itself. In this case, the test is relatively simple, as shown in Example 4-5, where all you need to determine is whether the y-coordinate of Units[j], expressed in Units[i] local coordinates, is positive.

Example 4-5. Limited-field-of-view check

.

.

.

if(LimitedView)

{

InView = (w.y > 0);

RadiusFactor = _LIMITEDVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

.

.

.The narrow-field-of-view model restricts each unit to seeing only what is directly in front of it, as illustrated in Figure 4-5.

The code check in this case is very similar to that for the wide-view case, where the visibility arc can be controlled by some factor. The calculations are shown in Example 4-6.

Example 4-6. Narrow-field-of-view check

.

.

.

if(NarrowView)

{

InView = (((w.y > 0) && (fabs(w.x) <

fabs(w.y)*

_FRONT_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _NARROWVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

.

.

.In this case, the factor, _FRONT_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR, controls the field of view directly in front of the unit. If this factor is equal to 1, the lines bounding the view cone are 45 degrees from the x-axis. If the factor is greater than 1, the lines move closer to the x-axis, effectively increasing the field of view. If the factor is less than 1, the lines move closer to the y-axis, effectively reducing the field of view.

If any of these tests pass, depending on which view model you selected for this demo, another check is made to see if Units[j] is also within a specified distance from Units[i]. If Units[j] is within the field of view and within the specified distance, it is visible by Units[i] and will be considered a neighbor for subsequent calculations.

The last if block in Example 4-3 shows this distance test. If the magnitude of the d vector is less than the Units[i]’s length times the RadiusFactor, Units[j] is close enough to Units[i] to be considered a neighbor. Notice how this prescribed separation threshold is specified in terms of the unit’s length times some factor. You can use any value here depending on your needs, though you’ll have to tune it for your particular game; however, we like using the radius factor times the unit’s length because it scales. If for some reason you decide to change the scale (the dimensions) of your game world, including the units in the game, their visibility will scale proportionately and you won’t have to go back and tune some new visibility distance at the new scale.

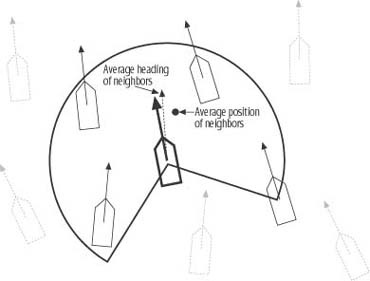

Cohesion implies that we want all the units to stay together in a group; we don’t want each unit breaking from the group and going its separate way. As we stated earlier, to satisfy this rule, each unit should steer toward the average position of its neighbors. Figure 4-6 illustrates a unit surrounded by several neighbors. The small dashed circle in the figure represents the average position of the four neighbors that are within view of the unit shown in bold lines with the visibility arc around itself.

The average position of neighbors is fairly easy to calculate. Once the neighbors have been identified, their average position is the vector sum of their respective positions divided by the total number of neighbors (a scalar). The result is a vector representing their average position. Example 4-3 already shows where the positions of the neighbors are summed once they’ve been identified. The relevant code is repeated here in Example 4-7 for convenience.

Example 4-7. Neighbor position summation

.

.

.

if(InView)

{

if(d.Magnitude() <= (Units[i].fLength *

RadiusFactor))

{

Pave += Units[j].vPosition;

Vave += Units[j].vVelocity;

N++;

}

}

.

.

.The line that reads Pave += Units[j].vPosition; sums the position vectors of all neighbors. Remember, Pave and vPosition are Vector types, and the overloaded operators take care of vector addition for us.

After DoUnitAI takes care of identifying and collecting information on neighbors, you can apply the flocking rules. The first one handled is the cohesion rule, and the code in Example 4-8 shows how to do this.

Example 4-8. Cohesion rule

.

.

.

// Cohesion Rule:

if(DoFlock && (N > 0))

{

Pave = Pave / N;

v = Units[i].vVelocity;

v.Normalize();

u = Pave - Units[i].vPosition;

u.Normalize();

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, u);

if(w.x < 0) m = -1;

if(w.x > 0) m = 1;

if(fabs(v*u) < 1)

Fs.x += m * _STEERINGFORCE * acos(v * u) / pi;

}

.

.

.Notice that the first thing this block of code does is check to make sure the number of neighbors is greater than zero. If so, we can go ahead and calculate the average position of the neighbors. Do this by taking the vector sum of all neighbor positions, Pave, and dividing by the number of neighbors, N.

Next, the heading of the current unit under consideration, Units[i], is stored in v and normalized. It will be used in subsequent calculations. Now the displacement between Units[i] and the average position of its neighbors is calculated by taking the vector difference between Pave and Units[i]’s position. The result is stored in u and normalized. u is then rotated from global coordinates to local coordinates fixed to Units[i] and the result is stored in w. This gives the location of the average position of Units[i]’s neighbors relative to Units[i]’s current position.

Next, the multiplier, m, for the steering force is determined. If the x-coordinate of w is greater than zero, the average position of the neighbors is located to the starboard side of Units[i] and it has to turn left (starboard). If the x-coordinate of w is less than zero, Units[i] must turn right (port side).

Finally, a quick check is made to see if the dot product between the unit vectors v and u is less than 1 and greater than minus -1.[3] This must be done because the dot product will be used when calculating the angle between these two vectors, and the arc cosine function takes an argument between +/−1.

The last line shown in Example 4-8 is the one that actually calculates the steering force satisfying the cohesion rule. In that line the steering force is accumulated in Fs.x and is equal to the direction factor, m, times the prescribed maximum steering force times the angle between the current unit’s heading and the vector from it to the average position of its neighbors divided by pi. The angle between the current unit’s heading and the vector to the average position of its neighbors is found by taking the arc cosine of the dot product of vectors v and u. This comes from the definition of dot product. Note that the two vectors, v and u, are unit vectors. Dividing the resulting angle by pi yields a scale factor that gets applied to the maximum steering force. Basically, the steering force being accumulated in Fs.x is a linear function of the angle between the current unit’s heading and the vector to the average position of its neighbors. This means that if the angle is large, the steering force will be relatively large, whereas if the angle is small, the steering force will be relatively small. This is exactly what we want. If the current unit is heading in a direction far from the average position of its neighbors, we want it to make a harder corrective turn. If it is heading in a direction not too far off from the average neighbor position, we want smaller corrections to its heading.

Alignment implies that we want all the units in a flock to head in generally the same direction. To satisfy this rule, each unit should steer so as to try to assume a heading equal to the average heading of its neighbors. Referring to Figure 4-6, the bold unit in the center is moving along a given heading indicated by the bold arrow attached to it. The light, dashed vector also attached to it represents the average heading of its neighbors. Therefore, for this example, the bold unit needs to steer toward the right.

We can use each unit’s velocity vector to determine its heading. Normalizing each unit’s velocity vector yields its heading vector. Example 4-7 shows how the heading data for a unit’s neighbors is collected. The line Vave += Units[j].vVelocity; accumulates each neighbor’s velocity vector in Vave in a manner similar to how positions were accumulated in Pave.

Example 4-9 shows how the alignment steering force is determined for each unit. The code shown here is almost identical to that shown in Example 4-8 for the cohesion rule. Here, instead of dealing with the average position of neighbors, the average heading of the current unit’s neighbors is first calculated by dividing Vave by the number of neighbors, N. The result is stored in u and then normalized, yielding the average heading vector.

Example 4-9. Alignment rule

.

.

.

// Alignment Rule:

if(DoFlock && (N > 0))

{

Vave = Vave / N;

u = Vave;

u.Normalize();

v = Units[i].vVelocity;

v.Normalize();

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, u);

if(w.x < 0) m = -1;

if(w.x > 0) m = 1;

if(fabs(v*u) < 1)

Fs.x += m * _STEERINGFORCE * acos(v * u) / pi;

}

.

.

.Next, the heading of the current unit, Units[i], is determined by taking its velocity vector and normalizing it. The result is stored in v. Now, the average heading of the current unit’s neighbors is rotated from global coordinates to local coordinates fixed to Units[i] and stored in vector w. The steering direction factor, m, is then calculated in the same manner as before. And, as in the cohesion rule, the alignment steering force is accumulated in Fs.x.

In this case, the steering force is a linear function of the angle between the current unit’s heading and the average heading of its neighbors. Here again, we want small steering corrections to be made when the current unit is heading in a direction fairly close to the average of its neighbors, whereas we want large steering corrections to be made if the current unit is heading in a direction way off from its neighbors’ average heading.

Separation implies that we want the units to maintain some minimum distance away from each other, even though they might be trying to get closer to each other as a result of the cohesion and alignment rules. We don’t want the units running into each other or, worse yet, coalescing at a coincident position. Therefore, we’ll enforce separation by requiring the units to steer away from any neighbor that is within view and within a prescribed minimum separation distance.

Figure 4-7 illustrates a unit that is too close to a given unit, the bold one. The outer arc centered on the bold unit is the visibility arc we’ve already discussed. The inner arc represents the minimum separation distance. Any unit that moves within this minimum separation arc will be steered clear of it by the bold unit.

The code to handle separation is just a little different from that for cohesion and alignment because for separation, we need to look at each individual neighbor when determining suitable steering corrections rather than some average property of all the neighbors. It is convenient to include the separation code within the same j loop shown in Example 4-3 where the neighbors are identified. The new j loop, complete with the separation rule implementation, is shown in Example 4-10.

Example 4-10. Neighbors and separation

.

.

.

for(j=1; j<_MAX_NUM_UNITS; j++)

{

if(i!=j)

{

InView = false;

d = Units[j].vPosition - Units[i].vPosition;

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, d);

if(WideView)

{

InView = ((w.y > 0) || ((w.y < 0) &&

(fabs(w.x) >

fabs(w.y)*_BACK_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _WIDEVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(LimitedView)

{

InView = (w.y > 0);

RadiusFactor = _LIMITEDVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(NarrowView)

{

InView = (((w.y > 0) && (fabs(w.x) <

fabs(w.y)*_FRONT_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)));

RadiusFactor = _NARROWVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR;

}

if(InView)

{

if(d.Magnitude() <= (Units[i].fLength *

RadiusFactor))

{

Pave += Units[j].vPosition;

Vave += Units[j].vVelocity;

N++;

}

}

if(InView)

{

if(d.Magnitude() <=

(Units[i].fLength * _SEPARATION_FACTOR))

{

if(w.x < 0) m = 1;

if(w.x > 0) m = -1;

Fs.x += m * _STEERINGFORCE *

(Units[i].fLength *

_SEPARATION_FACTOR) /

d.Magnitude();

}

}

}

}

.

.

.The last if block contains the new separation rule code. Basically, if the j unit is in view and if it is within a distance of Units[i].fLength ∗_SEPARATION_FACTOR from the current unit, Units[i], we calculate and apply a steering correction. Notice that d is the distance separating Units[i] and Units[j], and was calculated at the beginning of the j loop.

Once it has been determined that Units[j] presents a potential collision, the code proceeds to calculate the corrective steering force. First, the direction factor, m, is determined so that the resulting steering force is of such a direction that the current unit, Units[i], steers away from Units[j]. In this case, m takes on the opposite sense, as in the cohesion and alignment calculations.

As in the cases of cohesion and alignment, steering forces get accumulated in Fs.x. In this case, the corrective steering force is inversely proportional to the actual separation distance. This will make the steering correction force greater the closer Units[j] gets to the current unit. Notice here again that the minimum separation distance is scaled as a function of the unit’s length and some prescribed separation factor. This occurs so that separation scales just like visibility, as we discussed earlier.

We also should mention that even though separation forces are calculated here, units won’t always avoid each other with 100% certainty. Sometimes the sum of all steering forces is such that one unit is forced very close to or right over an adjacent unit. Tuning all the steering force parameters helps to mitigate, though not eliminate, this situation. You could set the separation steering force so high as to override any other forces, but you’ll find that the units’ behavior when in close proximity to each other appears very erratic. Further, it will make it difficult to keep flocks together. In the end, depending on your game’s requirements, you still might have to implement some sort of collision detection and response algorithm similar to that discussed in Physics for Game Developers (O’Reilly) to handle cases in which two or more units run into each other.

You also should be aware that visibility has an important effect on separation. For example, while in the wide-view visibility model, the units maintain separation very effectively; however, in the narrow-view model the units fail to maintain side-to-side separation. This is because their views are so restricted, they are unaware of other units right alongside them. If you go with such a limited-view model in your games, you’ll probably have to use a separate view model, such as the wide-view model, for the separation rule. You can easily change this example to use such a separate model by replacing the last if block’s condition to match the logic for determining whether a unit is in view according to the wide-view model.

Once all the flocking rules are implemented and appropriate steering forces are calculated for the current unit, DoUnitAI stores the resulting steering forces and point of application in the current unit’s member variables. This is shown in Example 4-11.

Example 4-11. Set Units[i] member variables

void DoUnitAI(int i)

// Do all steering force calculations...

.

.

.

Units[i].Fa = Fs;

Units[i].Pa = Pfs;

}Once DoUnitAI returns, UpdateSimulation becomes responsible for applying the new steering forces and updating the positions of the units (see Example 4-1).

The flocking rules we discussed so far yield impressive results. However, such flocking behavior would be far more realistic and useful in games if the units also could avoid running into objects in the game world as they move around in a flock. As it turns out, adding such obstacle avoidance behavior is a relatively simple matter. All we have to do is provide some mechanism for the units to see ahead of them and then apply appropriate steering forces to avoid obstacles in their paths.

In this example, we’ll consider a simple idealization of an obstacle—we’ll consider them as circles. This need not be the case in your games; you can apply the same general approach we’ll apply here for other obstacle shapes as well. The only differences will, of course, be geometry, and how you mathematically determine whether a unit is about to run into the obstacle.

To detect whether an obstacle is in the path of a unit, we’ll borrow from robotics and outfit our units with virtual feelers. Basically, these feelers will stick out in front of the units, and if they hit something, this will be an indication to the units to turn. We’ll assume that each unit can see obstacles to the extent that we can calculate to which side of the unit the obstacle is located. This will tell us whether to turn right or left.

The model we just described isn’t the only one that will work. For example, you could outfit your units with more than one feeler—say, three sticking out in three different directions to sense not only whether the obstacle is present, but also to which side of the unit it is located. Wide units might require more than one feeler so that you can be sure the unit won’t sideswipe an obstacle. In 3D you could use a virtual volume that extends out in front of the unit. You then could test this volume against the game-world geometry to determine an impending collision with an obstacle. You can take many approaches.

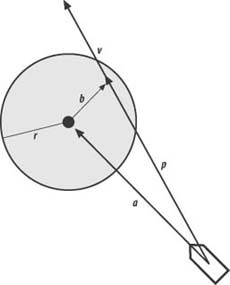

Getting back to the approach we’ll discuss, take a look at Figure 4-8 to see how our single virtual feeler will work in geometric terms. The vector, v, represents the feeler. It’s of some prescribed finite length and is collinear with the unit’s heading. The large shaded circle represents an obstacle. To determine whether the feeler intersects the obstacle at some point, we need to apply a little vector math.

First, we calculate the vector, a. This is simply the difference between the unit’s and the obstacle’s positions. Next, we project a onto v by taking their dot product. This yields vector p. Subtracting vector p from a yields vector b. Now to test whether v intersects the circle somewhere we need to test two conditions. First, the magnitude of p must be less than the magnitude of v. Second, the magnitude of b must be less than the radius of the obstacle, r. If both of these tests pass, corrective steering is required; otherwise, the unit can continue on its current heading.

The steering force to be applied in the event of an impending collision is calculated in a manner similar to the flocking rules we discussed earlier. Basically, the required force is calculated as inversely proportional to the distance from the unit to the center of the obstacle. More specifically, the steering force is a function of the prescribed maximum steering force times the ratio of the magnitude of v to the magnitude of a. This will make the steering correction greater the closer the unit is to the obstacle, where there’s more urgency to get out of the way.

Example 4-12 shows the code that you must add to DoUnitAI to perform these avoidance calculations. You insert this code just after the code that handles the three flocking rules. Notice here that all the obstacles in the game world are looped through and checked to see if there’s an impending collision. Here again, in practice you’ll want to optimize this code. Also notice that the corrective steering force is accumulated in the same Fs.x member variable within which the other flocking rule steering forces were accumulated.

Example 4-12. Obstacle avoidance

.

.

.

Vector a, p, b;

for(j=0; j<_NUM_OBSTACLES; j++)

{

u = Units[i].vVelocity;

u.Normalize();

v = u * _COLLISION_VISIBILITY_FACTOR *

Units[i].fLength;

a = Obstacles[j] - Units[i].vPosition;

p = (a * u) * u;

b = p - a;

if((b.Magnitude() < _OBSTACLE_RADIUS) &&

(p.Magnitude() < v.Magnitude()))

{

// Impending collision...steer away

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, a);

w.Normalize();

if(w.x < 0) m = 1;

if(w.x > 0) m = -1;

Fs.x += m * _STEERINGFORCE *

(_COLLISION_VISIBILITY_FACTOR *

Units[i].fLength)/a.Magnitude();

}

}

.

.

.If you download and run this example, you’ll see that even while the units form flocks, they’ll still steer well clear of the randomly placed circular objects. It is interesting to experiment with the different visibility models to see how the flocks behave as they encounter obstacles. With the wide-visibility model the flock tends to split and go around the obstacles on either side. In some cases, they regroup quite readily while in others they don’t. With the limited- and narrow-visibility models, the units tend to form single-file lines that flow smoothly around obstacles, without splitting.

We should point out that this obstacle avoidance algorithm will not necessarily guarantee zero collisions between units and obstacles. A situation could arise such that a given unit receives conflicting steering instructions that might force it into an obstacle—for example, if a unit happens to get too close to a neighbor on one side while at the same time trying to avoid an obstacle on the other side. Depending on the relative distances from the neighbor and the obstacle, one steering force might dominate the other, causing a collision. Judicious tuning, again, can help mitigate this problem, but in practice you still might have to implement some sort of collision detection and response mechanism to properly handle these potential collisions.

Modifications to the basic flocking algorithm aren’t strictly limited to obstacle avoidance. Because steering forces from a variety of rules are accumulated in the same variable and then applied all at once to control unit motion, you can effectively layer any number of rules on top of the ones we’ve already considered.

One such additional rule with interesting applications is a follow-the-leader rule. As we stated earlier, the flocking algorithm we discussed so far is leaderless; however, if we can combine the basic flocking algorithm with some leader-based AI, we can open up many new possibilities for the use of flocking in games.

At the moment, the three flocking rules will yield flocks that seem to randomly navigate the game world. If we add a leader to the mix, we could get flocks that move with greater purpose or with seemingly greater intelligence. For example, in an air combat simulation, the computer might control a squadron of aircraft in pursuit of the player. We could designate one of the computer-controlled aircraft as a leader and have him chase the player, while the other computer-controlled aircraft use the basic flocking rules to tail the leader, effectively acting as wingmen. Upon engaging the player, the flocking rules could be toggled off as appropriate as a dogfight ensues.

In another example, you might want to simulate a squad of army units on foot patrol through the jungle. You could designate one unit as the point man and have the other units flock behind using either a wide-visibility model or a limited one, depending on whether you want them in a bunched-up group or a single-file line.

What we’ll do now with the flocking example we’ve been discussing is add some sort of leader capability. In this case, we won’t explicitly designate any particular unit as a leader, but instead we’ll let some simple rules sort out who should be or could be a leader. In this way, any unit has the potential of being a leader at any given time. This approach has the advantage of not leaving the flock leaderless in the event the leader gets destroyed or somehow separated from his flock.

Once a leader is established, we could implement any number of rules or techniques to have the leader do something meaningful. We could have the leader execute some prescribed pattern, or chase something, or perhaps evade. In this example, we’ll have the leader chase or intercept the user-controlled unit. Further, we’ll break up the computer-controlled units into two types: regular units and interceptors. Interceptors will be somewhat faster than regular units and will follow the intercepting algorithms we discussed earlier in this book. The regular units will travel more slowly and will follow the chase algorithms we discussed earlier. You can define or classify units in an infinite number of ways. We chose these to illustrate some possibilities.

Example 4-13 shows a few lines of code that you must add to the block of code shown in Example 4-3; the one that calculates all the neighbor data for a given unit.

Example 4-13. Leader check

.

.

.

if(((w.y > 0) &&

(fabs(w.x) < fabs(w.y)*_FRONT_VIEW_ANGLE_FACTOR)))

if(d.Magnitude() <=

(Units[i].fLength * _NARROWVIEW_RADIUS_FACTOR))

Nf++;

.

.

.

if(InView &&

(Units[i].Interceptor == Units[j].Interceptor))

{

.

.

.

}

.

.

.The first if block shown here performs a check, using the same narrow-visibility model we’ve already discussed, to determine the number of units directly in front of and within view of the current unit under consideration. Later, this information will be used to determine whether the current unit should be a leader. Essentially, if no other units are directly in front of a given unit, it becomes a leader and can have other units flocking around or behind it. If at least one unit is in front of and within view of the current unit, the current unit can’t become a leader. It must follow the flocking rules only.

The second if block shown in Example 4-13 is a simple modification to the InView test. The additional code checks to make sure the types of the current unit and Units[j] are the same so that interceptor units flock with other interceptor units and regular units flock with other regular units, without mixing the two types in a flock. Therefore, if you download and run this example program and toggle one of the flocking modes on, you’ll see at least two flocks form: one flock of regular units and one flock of interceptor units. (Note that the player-controlled unit will be shown in green and you can control it using the keyboard arrow keys.)

Example 4-14 shows how the leader rules are implemented for the two types of computer-controlled units.

Example 4-14. Leaders, chasing and intercepting

.

.

.

// Chase the target if the unit is a leader

// Note: Nf is the number of units in front

// of the current unit.

if(Chase)

{

if(Nf == 0)

Units[i].Leader = true;

else

Units[i].Leader = false;

if(Units[i].Leader)

{

if(!Units[i].Interceptor)

{

// Chase

u = Units[0].vPosition;

d = u - Units[i].vPosition;

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, d);

if(w.x < 0) m = -1;

if(w.x > 0) m = 1;

Fs.x += m*_STEERINGFORCE;

} else {

// Intercept

Vector s1, s2, s12;

double tClose;

Vector Vr12;

Vr12 = Units[0].vVelocity -

Units[i].vVelocity;

s12 = Units[0].vPosition -

Units[i].vPosition;

tClose = s12.Magnitude() /

Vr12.Magnitude();

s1 = Units[0].vPosition +

(Units[0].vVelocity * tClose);

Target = s1;

s2 = s1 - Units[i].vPosition;

w = VRotate2D(-Units[i].fOrientation, s2);

if(w.x < 0) m = -1;

if(w.x > 0) m = 1;

Fs.x += m*_STEERINGFORCE;

}

}

}

.

.

.If you toggle the chase option on in the example program, the Chase variable gets set to true and the block of code shown here will be executed. Within this block, a check of the number of units, Nf, in front of and within view of the current unit is made to determine whether the current unit is a leader. If Nf is set to 0, no other units are in front of the current one and it thus becomes a leader.

If the current unit is not a leader, nothing else happens; however, if it is a leader, it will execute either a chase or an intercept algorithm, depending on its type. These chase and intercept algorithms are the same as those we discussed earlier in the book, so we won’t go through the code again here.

These new leader rules add some interesting behavior to the example program. In the example program, any leader will turn red and you’ll easily see how any given unit can become a leader or flocking unit as the simulation progresses. Further, having just the two simple types of computer-controlled units yields some interesting tactical behavior. For example, while hunting the player unit, one flock tails the player while the other flock seems to flank the player in an attempt to intercept him. The result resembles a pincer-type maneuver.

Certainly, you can add other AI to the leaders to make their leading even more intelligent. Further, you can define and add other unit types to the mix, creating even greater variety. The possibilities are endless, and the ones we discussed here serve only as illustrations as to what’s possible.

Get AI for Game Developers now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.