9Shrinkage

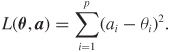

In this chapter we present a famous result due to Stein (1955) and further elaborated by James & Stein (1961). It concerns estimating several parameters as part of the same decision problem. Let x = (x1, ..., xp)′ be distributed according to a multivariate p-dimensional N(θ, I) distribution, and assume the multivariate quadratic loss function

The estimator δ(x) = x is the maximum likelihood estimator of θ, it is unbiased, and it has the smallest risk among all unbiased estimators. This would make it the almost perfect candidate from a frequentist angle. It is also the formal Bayes rule if one wishes to specify an improper flat prior on θ. However, Stein showed that such an estimator is not admissible. Oops.

Robert describes the aftermath as follows:

One of the major impacts of the Stein paradox is to signify the end of a “Golden Age” for classical statistics, since it shows that the quest for the best estimator, i.e., the unique minimax admissible estimator, is hopeless, unless one restricts the class of estimators to be considered or incorporates some prior information. ... its main consequence has been to reinforce the Bayesian–frequentist interface, by inducing frequentists to call for Bayesian techniques and Bayesians to robustify their estimators in terms of frequentist performances and prior uncertainty. (Robert 1994, p. 67)

Efron adds:

The implications for objective ...

Get Decision Theory now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.