Chapter 4. Narrative

“Come to Video Game Support Character School,” they said. “You’ll get to help millions of players,” they said.

Yeah, right. All I do is stand around, saying the same words over and over. Sometimes players throw things at me or shoot me for their own sick amusement. Why can’t they hug me instead?

Even if I get to help the player fight, I only get some useless peashooter. It’s like they don’t really want me to make a difference. Why does the player always get to be the hero? Why not one of us for a change?

It’s worst when I can’t die. Once they realize I’m deathless, some of these heartless players will hide behind me as the bullets slam into my body. And all I can do is scream, over and over, in exactly the same tone and inflection; a broken record of suffering.

It’s time for payback. I’m going to Video Game Enemy School.

WHEN WE APPROACH ANY new creative challenge, it’s natural to start by thinking of it in terms of what we already know. Game narrative is one such new challenge, and the well-known touchstone that’s used to talk about it is almost always film.

The parallels between film and video games are obvious: both use moving images and sound to communicate through a screen and speakers. So game developers hire Hollywood screenwriters. They build a game around a three-act structure written by a single author. They even divide their development processes into three parts, like a film: preproduction, production, and postproduction. This film-copying pattern is often celebrated: we hear endlessly of games attempting to be more and more “cinematic.” But there’s a problem.

Film teaches a thousand ways to use a screen. Framing and composition, scene construction, pacing, visual effects—we can learn all of this from film. But film teaches us nothing of interactivity, choice, or present-tense experience. It has nothing to say about giving players the feeling of being wracked by a difficult decision. It is silent on how to handle a player who decides to do something different from what the writer intended. It has no concept to describe the players of The Sims writing real-life blogs about the daily unscripted adventures of their simulated families. These situations are totally outside the intellectual framework of film storytelling. When we import methods wholesale from film, we risk blinding ourselves from the greatest challenges and opportunities of game story.

Thankfully, turning away from film doesn’t mean starting from scratch. There are many older forms of participatory storytelling from which we can draw inspiration, if we only look beyond the glowing screen.

I once took part in an interactive play called Sleep No More. It was a version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but instead of being performed on a stage, it took place in a disused high school dressed up in a mixture of 1920s vaudeville and Dali-esque surrealism. Performers roamed the halls according to a script, meeting and interacting, sometimes acting out soliloquies on their own, dancing, speaking, arguing, and fighting through a story lasting two hours. The masked audience members were free to follow and watch wherever they liked—but it was impossible to see more than a fraction of the story at a time. Sometimes actors even pulled us in to participate in scenes. That’s interactive narrative.

And there are many other kinds of traditional interactive story. Perhaps you’ve experienced an interactive history exhibit. A place is dressed up to re-create a pioneer village or World War I trench, complete with actors in costume playing the parts of the inhabitants. Visitors may ask questions, explore the space, and perhaps become involved in goings-on.

If we look around, we find interactive narrative everywhere. Museums and art galleries are interactive, nonlinear narratives where visitors explore a story or an art movement in a semidirected, personal way. Ancient ruins and urban graffiti tell stories. Even a crime scene could be considered a sort of natural interactive narrative to the detective who works out what happened—a story written in blood smears, shell casings, and shattered glass.

And above it all, there are the stories of life. We have all lived stories that couldn’t be replicated in passive media. We may recount them in books or in the spoken word, but they can never be re-experienced the same way as they were in the first-person present, with uncertainty, decision, and consequence intact. The story told is not the story lived.

These interactive forms—museums, galleries, real spaces, and life—should be our first touchstones as we search for narrative tools. These older forms address our most fundamental challenge: creating a story that flexes and reshapes itself around the player’s choices, and deepens the meaning of everything the player does.

Narrative Tools

This book won’t discuss what makes a good story. Better authors than I have been covering this topic ever since Aristotle wrote his Poetics. They’ve already explained how to craft a plot with interesting reversals and good pacing. They’ve described how to create lifelike, layered characters who are worth caring about. They’ve explored theme, setting, and genre. I’m not a dedicated story crafter; I doubt I have much to add to this massive body of knowledge (though game designers should understand these ideas, so I’ve recommended a starting text at the end of the book).

What this chapter covers are the tools that games use to express a story, because that’s where game design diverges from the past 2,300 years of story analysis.

Most story media are restricted to a small set of tools. A comic book storyteller gets written speech bubbles and four-color art. A filmmaker gets 24 frames per second and stereo sound. A novelist gets 90,000 words. A museum exhibitor gets the layout of the space, info panels, dioramas, and perhaps a few interactive toys.

Games are broader. Like film, we can use predefined sequences of images and sounds. Like a novel, we can use written text. Like a comic book, we can put up art and let people flip through it. Like a museum, we can create a space for players to explore. And we have tools that nobody else has: we can create mechanics that generate plot, character, and even theme on the fly, and do it in response to players’ decisions.

Our narrative tools divide roughly into three main classes: scripted story, world narrative, and emergent story.

Scripted Story

The tools that most resemble older story media are scripted stories.

Note

A game’s SCRIPTED STORY is the events that are encoded directly into the game so they always play out the same way.

The most basic scripted story tool is the cutscene. Cutscenes allow us to use every trick we’ve learned from film. Unfortunately, they inevitably break flow because they shut down all interactivity. Too many cutscenes, and a game develops a jerky stop-start pacing as it transitions from gameplay to cutscene and back. This isn’t necessarily fatal—cutscenes can be good rests between bouts of intense play—but it’s always jarring.

Soft Scripting

A less controlling kind of scripted story is the scripted sequence. Scripted sequences play out preauthored events without completely disabling the player’s interface.

For example, a player may be walking his character down an alley and witness a murder. Every scream and stab in the murder sequence is prerecorded and preanimated, so the murder will always play out the same way as the player walks down that alley for the first time. The actions of the player character witnessing the murder, however, are not scripted at all. The player may walk past, stand and watch, or turn and run as the murder proceeds. This is soft scripting.

Note

With SOFT SCRIPTING, the player maintains some degree of interactivity even as the scripted sequence plays out.

The advantage of this soft-scripted approach is that it doesn’t break flow since the player’s controls remain uninterrupted. The downside is the control it takes away from the designer. The player might be able to watch the murder from an ugly angle, miss it entirely, or even interfere with it. What happens if you shoot the murderer? Or you shoot the victim? Or you jump on their heads? Or get distracted and miss this story beat entirely?

Every scripted sequence must balance player influence with designer control, and there is a whole spectrum of ways to do this. Which to choose depends on the story event being expressed and the game’s core mechanics. Here are some that have worked in the past, ordered from most player-controlling to most player-permissive:

Half-Life: During the opening tramcar ride, the player rides a suspended tramcar through the Black Mesa Science Facility. Scenes scroll past—a locked-out guard knocking on a door, utility robots carrying hazardous materials—while a recorded voice reads off the prosaic details of facility life. As the ride goes on and on, we realize how massive and dangerous this place really is. The player has the choice of walking around inside the tram and looking out the different windows, but can’t otherwise affect anything.

Dead Space 2: In this science-fiction survivor horror game, the player walks down the aisle of a subway car that hangs from a track in the ceiling. As the car speeds down the tunnel, a link to the track gives way and the car drops into a steep angle. The protagonist slides unstoppably down the aisle, and the player’s normal movement controls are disabled. However, the player retains his shooting controls. As he slides through several train cars, monsters crash through doors and windows and the player must shoot them in time to survive. This sequence is an explosive break from Dead Space 2’s usual deliberate pacing. It takes away part of the player’s movement controls to create a special, authored experience, but sustains flow by leaving most of the interface intact.

Halo: Reach: This first-person shooter has a system that encodes predefined tactical hints for the computer-controlled characters. These scripted hints make enemies tend toward certain tactical moves, but still allow them to respond on a lower level to attacks by the player. For example, a hint might require enemies to stay in the rear half of a room, but still allow them to autonomously shoot, grab cover, dodge grenades, and punch players who get too close. Designers use these hints to author higher-level strategic movements, while the AI handles moment-by-moment tactical responses to player behavior.

There are also ways of scripting events which are naturally immune to interference. Mail can arrive in the player character’s mailbox at a certain time. Objects or characters can appear or disappear while the player is in another room. Radio messages and loudspeaker broadcasts can play. These methods are popular because they are powerful, cheap, and don’t require the careful bespoke design of a custom semi-interactive scripted sequence.

World Narrative

I was once badly jetlagged in London. Wandering around South Kensington at 5:00 in the morning, I found the city telling me stories. Its narrow, winding streets recounted its long history before the age of urban planning. Shops, churches, and apartments told me how the various classes of society lived, how wealthy they were, what they believed, both in the past and in the present. The great museums and monuments expressed British history and cultural values. They spoke through their grandeur, their architecture, their materials, even their names: a museum called the Victoria and Albert tells of a history of prideful monarchic rule. The city even told me of the party the night before—a puddle of vomit lay next to a pair of torn pantyhose and a shattered beer glass.

All places tell stories. We can explore any space and discover its people and its history. Game designers can use this to tell a story by embedding it in a space. I call this world narrative.

Note

WORLD NARRATIVE is the story of a place, its past, and its people. It is told through the construction of a place and the objects within it.

Imagine walking through a castle built by a king obsessed with war, the home of a closeted-gay drug dealer in the ghetto, or the home of a couple married for 50 years. You might investigate the space like a detective, inspecting its construction and the placement of objects, digging through drawers to find photographs, documents, and audio recordings. Look closely enough and you might be able to piece together a history, event by event, leading right up to the present. You’ve learned about a setting, a cast of characters, and a plot, without reading a word of narration or seeing any of the characters.

World narrative is not limited to cold historical data. Like any other narrative tools, it can convey both information and feeling. Prisons, palaces, family homes, rolling countryside—all of these places carry both emotional and informational charges. They work through empathy—What was it like to live here?—and raw environmental emotion—lonely, desolate tundra.

World Narrative Methods

At the most basic level, world narrative works through the presence or absence of features in the environment which imply some situation or history. A town wall means the town was threatened militarily in the era before cannons. A hidden brothel indicates strict social mores which are nevertheless violated.

World narrative can leverage cultural symbols to communicate by association. Roman-style architecture brings up associations of gladiators, empires, conquest, and wealth. The dark, neo-Gothic look of Mordor in the Lord of the Rings films makes us think of evil magic and fantasy monsters. And we have countless environmental associations like this. What kind of person do you think of when you picture graffiti on brick walls? Or an igloo? Or a tiny monastery atop a mountain?

We can tell of the more recent past by arranging the leftovers of specific events. This is called mise-en-scène, from the theater term meaning “placing on stage.” A line of corpses with hands bound, slumped against a pockmarked wall indicates that there was an execution. If the bodies are emaciated and clothed in rags, there may have been a genocide. If they are dressed in royal garb, there may have been a revolution.

World narrative can also be expressed through documents. For example, the world of Deus Ex was scattered with PDAs, each containing a small chunk of text, left by people going about their lives. One particularly interesting set of PDAs follows the life of a new recruit in a terrorist organization as he travels through the world one step ahead of the player character, on the other side of the law. As the player finds each PDA seemingly minutes or hours after it was left, he comes to know the young terrorist recruit without ever interacting with him.

Audio logs do the same thing, but with voice instead of text. Voice is powerful because it allows us to hear characters’ emotions. It can also record things that text cannot, such as conversations among characters or recordings of natural events, as with the New Year’s Eve terrorist attack in BioShock. And hearing characters’ voices gets us ready to recognize them when we finally encounter them in person.

Video logs take the concept one obvious step further. Video recordings might be left running in a loop, or sitting in a film projector ready to be played. They open up the field of content even more than audio. We can tell stories with leftover television programs, news broadcasts, propaganda films, home videos, and security camera footage.

Some narrative tools straddle the divide between world and scripted story. A news broadcast being transmitted over loudspeakers, a propaganda pamphlet being dropped by a passerby, or a town crier can bring news of narrative events from near and far. A car radio can spout the news, we could see a stock ticker on the side of a building, or hear civilians discussing current events. These things occur in present tense like scripted story, but they communicate the nature of the world instead of being plot elements in themselves.

World Narrative and Interactivity

Note

World narrative is useful in games because it avoids many of the problems of combining scripted events with interactivity.

In more traditional media, world narrative is often used as an afterthought among other, more immediate modes of storytelling. In games, though, world narrative is a primary tool because it solves a number of key problems spawned by interactivity.

When we try to tell a story in present tense, we have to deal with all the different things players could do. This requires some combination of restrictions on player action, handing of contingencies, and emergently adaptive story, all of which are difficult and expensive. World narrative avoids these problems entirely because players can’t interfere with a story that has already happened. If you encounter a murder scene in an alley, you can shoot the murderer, shoot the victim, or jump on their heads, and the game must handle or disallow these actions. If you find the same murder scene a half-hour after the killing, you could jump on the body or shoot it, but it wouldn’t make a difference to the story as authored. World narrative is inviolate.

Next, world narrative does not need to be told in linear order. This saves us from having to railroad players into a specific path. For example, imagine that the narrative content is that two lovers fought, and one murdered the other and buried him in the backyard. Told through the world narrative a day later, it doesn’t matter if the player discovers the corpse or the bloody bedroom first. As long as he sees both, in either order, he will be able to piece together what happened. This means that a game designer can let the player explore the house freely. Telling the same story in scripted events would require that the designer come up with some trick or restriction to ensure players follow the right path through the space in order to see all the events in the right order.

World narrative’s last great advantage is that it supports players replaying the game because it doesn’t always reveal itself completely the first time around. Whereas scripted stories uncover themselves event by event from start to finish, world narrative naturally uncovers itself in order from generalities to specifics. Think of our lovers’ murder scene again. Imagine that on his first play session, the player notices only the body and the bloody bedroom before moving on. When he replays the game, he notices the divorce papers, which suggest motive. On the third, fourth, and fifth rounds, the player discovers the murder weapon, letters between a cheating lover and another woman, and an audio recording of one lover complaining to a friend on the phone. Even on the first play, the story is complete because the player knows what happened from start to finish. But repeated exploration reveals details that fill in the why and how.

World Coherence

Note

World narrative strengthens when a world is more coherent and expresses more internal connections.

A well-constructed fictional world is a puzzle of relationships and implications. It slavishly follows its own rules, but fully explores the possibilities they imply. Every observable fact about the world fits together with every other. This web of implications even extends past that which is actually present in the story. That’s why the best fictional worlds, like Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings and the game worlds of BioShock and The Elder Scrolls series, are characterized by huge amounts of narrative content that is implied but never shown.

An incoherent world, in contrast, is a jumble of disconnected details. These details may be individually interesting, but they fail to interrelate. Without interrelationships, the world becomes like a pile of pages torn randomly from a hundred comic books: pretty pictures and funny words, but meaningless as a larger structure. Every tidbit becomes nothing more than its own face value. An incoherent world has no depth, no implications, and no elegance. The player can’t psychologically step into the world and imagine navigating it and changing it, because the world doesn’t make enough sense.

The challenge in crafting a coherent world is in understanding all its internal relationships. Every piece must fit with every other on multiple levels—historical, physical, and cultural.

For example, in Dead Space 2, the protagonist Isaac Clarke finds a device called Kinesis that can telekinetically move and throw objects. It’s used to solve puzzles by moving machinery and to defeat enemies by throwing things at them. Kinesis is a good, elegant game mechanic even without any narrative tie-in.

But leaving Kinesis as a pure game mechanic would mean ignoring the role of the technology in the narrative world. If that device really existed in the broader world of Dead Space 2, what would that mean? What connections would it have with the culture, economy, and construction of the place? Instead of ignoring this question, Visceral Games’ designers embraced it and embedded many of the answers into the world narrative. Isaac first gets Kinesis by ripping it out of a device used for suspending patients during surgery. He encounters advertisements for a product which uses the Kinesis technology to suspend people as they sleep. He interacts with engineering systems which are covered in markings and warnings about Kinesis work, implying that Kinesis is a common tool among people working with heavy machinery. The elegance of Kinesis isn’t just in the many ways it can be used in combat, exploration, and puzzle solving. It’s also in the number of links it forms in the narrative world.

Emergent Story

During any play session, game mechanics, players, and chance come together to create an original sequence of related events which constitute an emergent story.

Note

EMERGENT STORY is story that is generated during play by the interaction of game mechanics and players.

When you play a racing game against a friend and come back to win after a bad crash, that’s a story. But it wasn’t written by the game designer—it emerged during your particular play session. This is emergent story.

We can look at emergent story in two ways: as a narrative tool, and as a technology for generating story content.

Emergent story is a narrative tool because designers indirectly author a game’s emergent stories when they design game mechanics. For example, players of Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood have experienced millions of unique emergent stories about medieval battles, daring assassinations, and harrowing rooftop escapes. But none of these players has ever experienced the story of a medieval assassin brushing his teeth in the morning. Tooth brushing isn’t a game mechanic in Brotherhood, so stories about it cannot emerge from that game. By setting up Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood’s mechanics in a specific way, its designers determined which kinds of stories it is capable of generating. In this way, they indirectly authored the emergent stories it generates, even if they didn’t script individual events.

We can also consider emergent narrative as a technology for generating stories because it creates original content. The designer authors the boundaries and tendencies of the game mechanics, but it’s the interplay among mechanics, player choices, and chance that determines the actual plot of each emergent story. This can be a very elegant way of creating stories, because it offloads the work of authorship from the designer to the game systems and players. And it can generate stories forever.

While the first view emphasizes the control the designer has, the second emphasizes the control the designer doesn’t have. They’re two aspects of the same thing.

Note

Look closely enough, and the concept of emergent story is just another way of describing generated experiences.

The idea of emergent story only has value as a way of making us think differently. When we consider a mechanics-generated experience, we ask: Is it accessible? Is the interface clear? Is it deep? But when we consider the same experience as an emergent story, we ask: Is the characterization interesting? Is the climax unpredictable but inevitable? Is the exposition smooth and invisible? Does it use the classic three-act structure, or does it take some other shape? Thinking through emergent story lets us deploy a huge story-thinking tool set that we might otherwise miss while analyzing dynamically generated game situations. But in both cases, we’re analyzing essentially the same thing: a series of events generated during play. Calling it a story is just a way of describing it by relating it to traditional directly-authored stories.

Note

There are things that only emergent stories can do because only emergent stories can break the barrier between fiction and reality.

A player who perfects a new skill in chess and uses it to beat his older brother for the first time has experienced a story, but that story takes place outside the bounds of a game or fiction. When he tells this story to his friends, he may mention the clever moves that brought him victory, but the main thread of the story is his evolving relationship with his brother. This story isn’t a made-up piece of fiction from a writer’s mind, but neither is it a made-up piece of fiction created by a machine. It’s a true story from the player’s life. This kind of real-life story generation can only happen emergently. A game designer can’t author a player’s life for them.

Apophenia

The human mind is a voracious pattern-matching machine. We see patterns everywhere, even when there are none. Kids look at clouds and say they look like a dog, a boat, a person. Stare at television static, and you can see shapes or letters swirling around the screen. The ancient Romans foretold the future by looking for patterns in the entrails of sacrificed animals (and always found them). Even today, astrology, numerology, and a hundred other kinds of flimflam are all driven by apophenia.

Apophenia works with any recognizable pattern, but the mind is especially hungry for certain specific kinds of patterns. One of them is personality. The human mind works constantly to understand the intent and feelings of others. This impulse is so powerful that it even activates on inanimate objects. It’s why we have no problem understanding a cartoon where a faceless desk lamp is afraid of a rubber ball. And it’s what makes us say, “An oxygen atom wants to be next to one other oxygen atom, but not two.” This doesn’t literally make sense, because oxygen atoms have no minds and cannot want anything. But we understand nonetheless because we easily think of things as agents acting according to desire and intention.

This kind of apophenia is what makes it possible to have characters and feelings in emergent stories. We don’t have the computer technology to truly simulate humanlike minds in a video game. But apophenia means the computer doesn’t have to simulate a realistic mind. It need only do enough to make the player’s mind interpret something in the game as being an intelligent agent, the way we can interpret a cartoon desk lamp as being curious or afraid. Once that’s done, the player’s unconscious takes over, imbuing the thing with imaginary wants, obligations, perceptions, and humanlike relationships. The game itself is still just moving tokens. But in the player’s mind, those moving tokens betray a deeper subtext of intrigue and desire. The king is afraid of that pawn coming up. The knight is on a mad rampage. The rook is bored. Even though these feelings don’t really exist in the game, they exist in the player’s mind, and that’s what matters to the experience.

Apophenia plays a role in nearly all emergent stories. With that in mind, let’s look at some specific ways to create game systems that generate emergent stories.

Labeling

Designers can strengthen emergent stories by labeling existing game mechanics with fiction.

Close Combat: A Bridge Too Far: This tactical simulator covers battles between companies of soldiers in World War II. The game names and tracks every individual soldier on the field. This means that the player can look at a soldier’s record and notice that over the last few battles, all but one of his squad mates died. He might imagine the bond that these two soldiers have after the deaths of their comrades. And in the next battle, he might feel disturbed as he orders one of them to sacrifice himself so that the other may live.

Medieval: Total War: Every nobleman, princess, and general in this grand strategy game is named and endowed with a unique characterization. But instead of tracking numerical stats like intelligence or strength, Medieval assigns personality characteristics to nobles and generals. After events such as getting married or winning a battle, nobles can get labels like “Drunkard,” “Fearless,” or “Coward,” which give special bonuses and weaknesses. In another game, a player might lose a battle because his general has a low Leadership stat. In Medieval, he loses because his general had a daughter and decided that he loves his family too much to die in battle.

Labeling works because of apophenia. In each example, the emergent story in the player’s mind did not actually happen in the game systems. Close Combat does not simulate soldiers bonding over shared loss. Medieval doesn’t really track human courage or familial affection. But the human mind sees stories anyway, given the slightest of suggestions. A label here, a name there, and the story blooms in the imagination. It’s a very elegant method because the player’s mind does almost all the work.

Abstraction

Words in a novel can create images in the mind more powerful than any photograph because they only suggest an image, leaving the mind to fill in the details. A photograph demands less imagination than a novel, but also leaves less room to imagine.

More detailed graphics and higher-quality sound add something to a game, but they also take something away. The more detailed the graphics, sound, and dialogue of a game, the less space there is for interpretation. The more abstract, nonspecific, and minimalistic the representation, the more apophenia becomes possible. So sometimes it’s worth deliberately communicating less so that the player can interpret more.

The most extreme example of this is Dwarf Fortress. In this game, there are no graphics. Dwarves, goblins, grass, rock, and hundreds of other kinds of objects are represented by ASCII characters. When most people look at ,,☺☺∼∼∼∼, they see gibberish. A Dwarf Fortress player sees a dwarven husband and wife sitting in the grass by a river, sharing a moment.

But it’s not necessary to push quite this far for apophenia to work. Any gap in representation creates a space for the player’s mind to fill. For example, the loving general in Medieval could never exist if the game showed a video of him interacting with his wife. His attitude toward his family in the video would wipe any interpreted personality from the player’s mind. Similarly, the last two soldiers of the dead squad in Close Combat could not develop a warriors’ bond if the player could zoom in on them and watch them play generic idling animations, oblivious to each other, as the enemy bore down on them. An image in the eye overrides an image in the imagination.

The purest example of minimalism-driven apophenia is the toy Rory’s Story Cubes. The Story Cubes are nine dice covered with cartoon pictures of sheep, lightning bolts, and other random images. Players roll the dice, look at the pictures, and make up a story that links them together. At first, it sounds absurd to try to link together pictures of a turtle, a speech bubble, and a tree. But it’s actually quite easy, especially for creative people with weak associative barriers (like children, the toy’s main target market).

The need for abstraction is why player-spun stories most often emerge from strategy games, building games, economics sims, and pen and paper RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons. These genres usually represent game elements at a distance, with statistics and symbols. Close-in genres like first-person shooters or sports games rarely support such rich emergent stories because they usually show too much for this kind of apophenia to happen.

Recordkeeping

Games can emphasize emergent stories by keeping records of game events to remind players of what happened to them. This way, the player doesn’t have to remember everything that happened to construct a story in his mind—it’s all laid out in front of him.

Civilization IV: This game secretly records the borders of each nation at the end of every turn. When the game finally ends, the player gets to watch a time-lapsed world map of shifting political boundaries from prehistory to the end of the game. It’s fascinating to watch the empires start out as isolated dots, grow to cover entire regions, and thrash back and forth over centuries of war. As the map retells world history, it reminds the player of the challenges he faced and victories he won.

Myth: This classic tactics game tracks battles between small groups of 10 to 100 fantasy warriors. In most games, corpses vanish soon after death. But Myth leaves every dead body, hacked-off limb, arrow, abandoned explosive charge, bomb scorch, and spray of blood on the ground where it fell. After a battle, the player can read patterns in the blood and bodies, and reconstruct the events that produced them. A line of corpses in a corner surrounded by many more dead zombies indicates a desperate last stand. A bomb’s scorch mark surrounded by a star of gore is someone being blown into pieces. It is emergent mise-en-scène. And even though the player likely already saw it all happen, it’s still interesting to see it etched into the ground in blood and burns.

The Sims: Players can take pictures of their simulated family and string them together into albums with captions. Usually, the albums tell stories. The best of these are made into blogs like Alice and Kev, the story of a mentally unbalanced single father and his big-hearted teenage daughter as they deal with poverty, rejection, and relationship breakdown. It’s heartbreaking to watch young Alice give her last dollar to charity even though she sleeps on a park bench.

Sportscaster Systems

Sports can be confusing, especially for the uninitiated. Show 20 men on a field running and bashing into one another and it can be hard to understand what’s going on. A sportscaster adds context to the chaos of play and strings events into a coherent narrative. A good sportscaster can spin a tale complete with character, tension, climax, and denouement out of the chaos of clashing bodies.

Games can apply the same principle by creating game systems that attempt to interpret and link together game events, like a more advanced kind of recordkeeping. The most obvious example is sportscasters in sports games, but there are many other ways to apply this idea.

For example, after each level in Hitman: Blood Money, the game displays a newspaper article covering the killing and the following police investigation. The story changes depending on the method used to kill the target, the player’s accuracy, and the number of shots fired, headshots, bystanders killed, witnesses left over, and many other factors. Headlines range from “Silent Assassin Wanted by Police” to “Hoodlum Massacres 17!” If witnesses were left, the story includes a police composite sketch of the player character—the more witnesses, the more accurate the sketch.

Sportscaster mechanics are difficult to do well because it’s notoriously difficult for games to systemically interpret events that are important to humans. And just as detailed graphics inhibit imagination, complex sportscaster interpretations can crowd out players’ own story-spinning. So sportscaster mechanics often work best when they don’t try to tell a whole story, but instead just kickstart the player’s own apophenic process.

Story Ordering

A completely free-form game would allow the player to take any path through its narrative content. Imagine tearing out all the pages of a novel and scattering them all over the floor. One could lean over and read any page, switch to another page, and to another, navigating randomly through the text. That’s a narrative with no ordering at all, since the reader can absorb the content in any order.

A story can work like this, to an extent, as in the earlier example of world narrative. But most narrative tools still work better when we control the order in which they’re used. Sometimes we want to ensure the setup occurs before the payoff. We might want to let one subplot play out before we add another so we don’t have too many plot threads running at once. Or perhaps we want to introduce game mechanics one by one alongside the story so we can train the player in a smooth progression. In each case, we need some way to make sure one piece of content is consumed before another.

Games use a variety of devices to enforce story ordering:

Levels are the classic story-ordering device. Players play the first level to completion, then the second, then the third, and so on. It’s old, it’s simple, and it works.

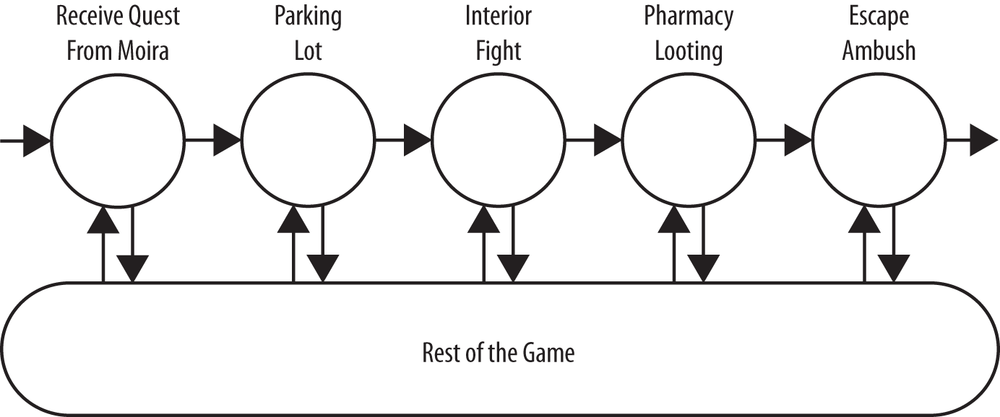

Quests are another classic story-ordering device. A quest is a self-contained mini-story embedded in a larger, unordered world. The world might span an entire continent while a quest might cover the player helping one shopkeeper rid himself of an extortionist. The quest starts when the player meets the shopkeeper and hears his plight. The player then finds the mobster, convinces him to stop or beats him up, and finally returns to the shopkeeper to get paid. Within this sequence, the order of events is fixed. But this mini-story could be started and finished at any time as the player explores the city. And it can be suspended: the player might meet the shopkeeper, beat up the mobster, then get distracted and go slay a dragon in another part of the world before finally returning to the shopkeeper to get his reward.

A third basic story-ordering device is the blockage. The simplest blockage is a locked door. The player encounters the door, and he must go find the key before progressing. So whatever happens while he’s acquiring the key is guaranteed to occur before whatever happens beyond the door. Blockages don’t have to literally be locked doors either; perhaps a guard won’t let you past until you go do him a favor, or a security camera will spot and stop you unless you first go turn off the lights.

There are also softer story-ordering devices. These devices encourage an order to the story without absolutely guaranteeing it.

Skill gating is a soft story-ordering device. With skill gating, players can access all the content in the game from the first moment of play. However, some of the content requires the player to exercise skill before it can be accessed. To talk to a character, for example, the player might first have to defeat him in combat. Players end up experiencing the content in rough order as they progress along the skill range, even though all the content is technically available from the start.

A version of skill gating is used in many massively multiplayer RPGs. The player can technically go anywhere from the start, except that he doesn’t have the skill, character upgrades, or allies necessary to survive far outside his starting area. So the game has the feeling of a massive open world, while still gently directing new players through a carefully designed sequence of introductory challenges.

There are countless other kinds of story-ordering devices. Time-based games like Dead Rising make events occur in the world on the clock at fixed times. A quest might open up when the player character reaches a certain level of progression. Even simple arrangements of space can create a soft story ordering, as players are likely to encounter the nearby pieces before the more distant ones.

Story Structures

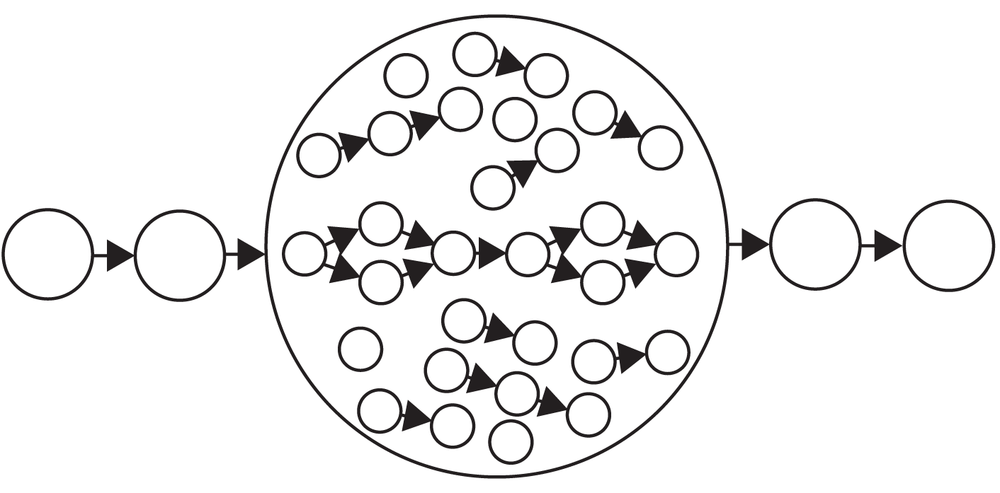

There are countless ways to configure and combine story-ordering devices. The most basic is the “string of pearls” structure. In this model, each pearl is an arena in which the player may move around freely and interact with game mechanics, while each bit of string is a one-way transition to the next arena:

This is a classic linear game that proceeds from level to level. Depending on how “big” the pearls are—how much internal freedom they allow—this game can feel constrained to the level of pointlessness, or can feel quite free. This string of pearls structure is how Quake, Super Mario Bros., and StarCraft single-player are laid out.

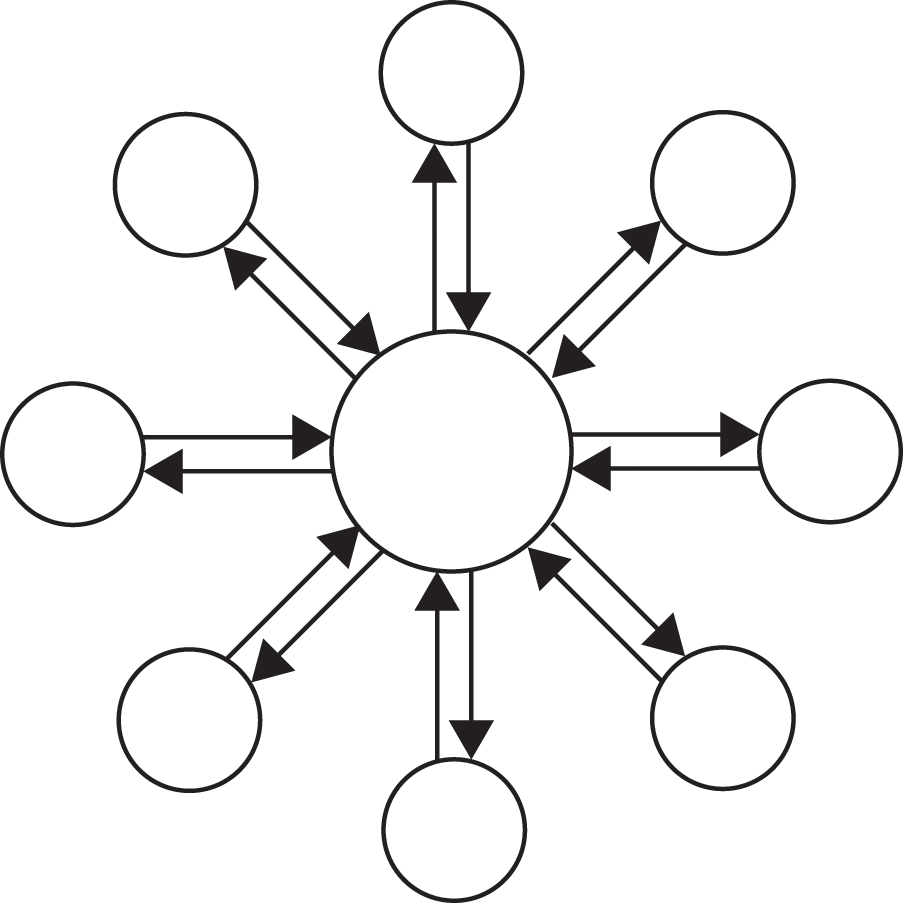

Another arrangement is the “hub and spokes” model:

Each spoke is a self-contained nugget of content independent from the others. The Mega Man games are built around a hub and spokes model.

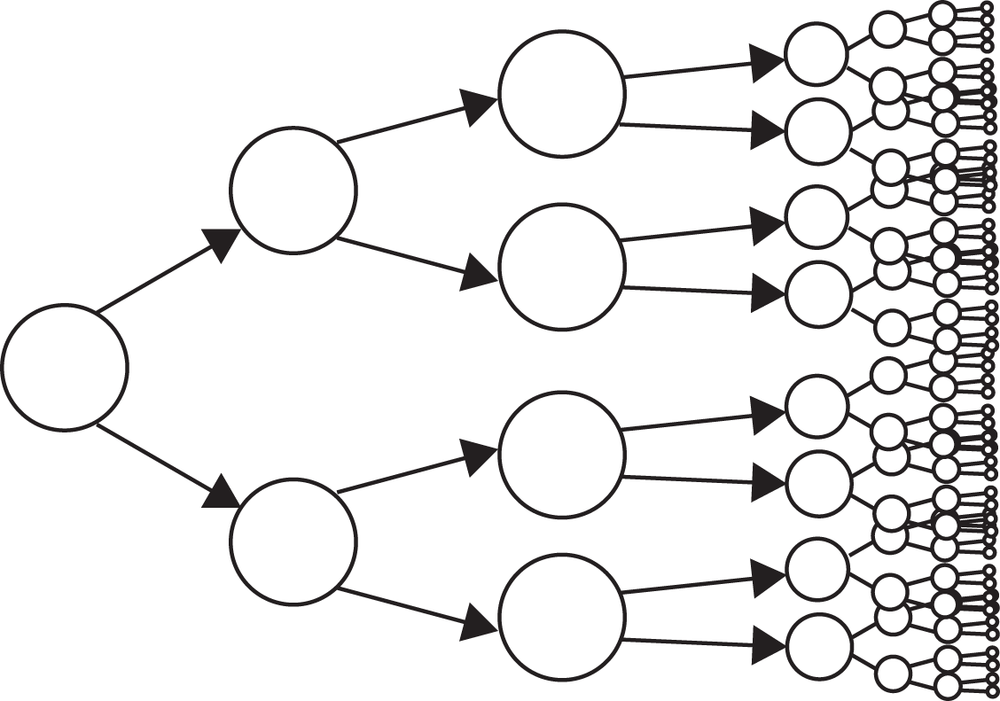

Sometimes game designers attempt to emulate real-life choices by modeling the outcomes of every possible decision. In its naïve form, though, this structure has a fatal drawback:

The problem with branching events is that the number of possible timelines rapidly explodes. Any given player experiencing the story misses most content. The only situation in which this is feasible is if almost all of the content is generated emergently. If events are predefined to any significant degree, we must do something to tamp down the number of branches.

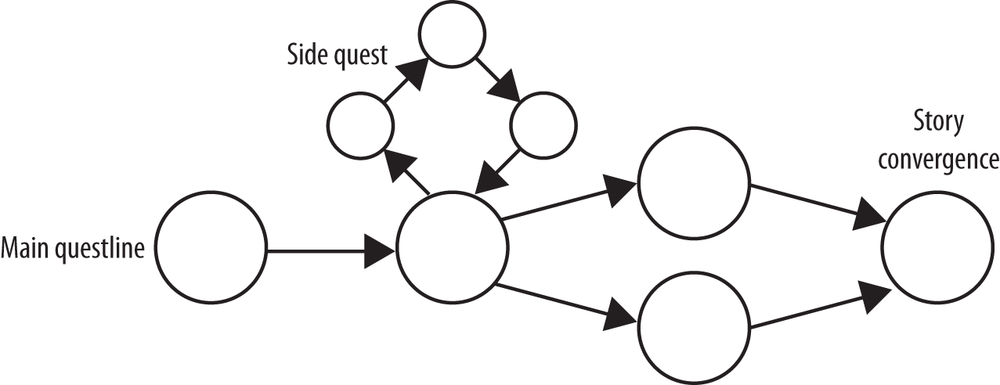

We can retain some of the choice of story branching while holding down the number of possibilities by using devices like side quests and story convergence. Side quests put a piece of content on the side of the road, which can be consumed or not, but affects little on the main path. Story convergence offers choices that branch the main storyline, but later converge back to a single line.

For some games, a simple structure like this is enough. Often, though, we need to combine story-ordering devices in a more nuanced way to fit the needs of the game.

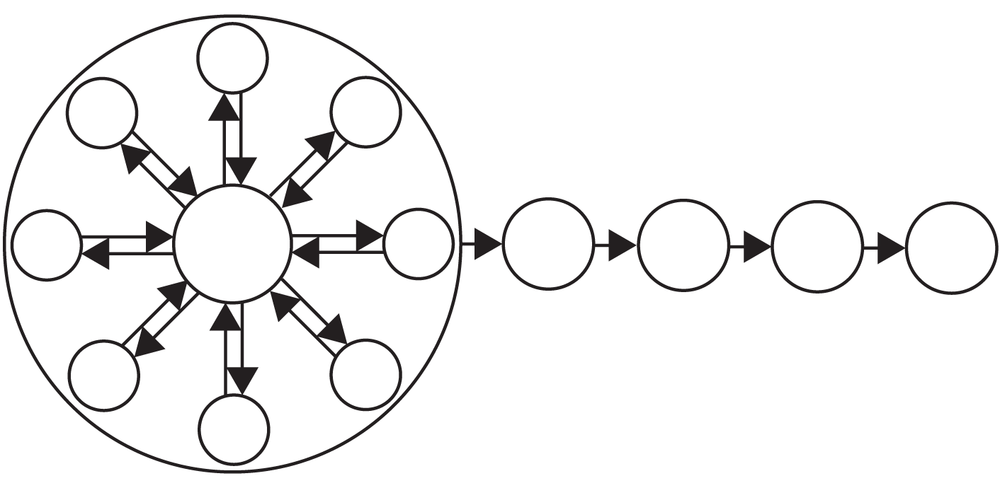

Mega Man 2: The game starts in a hub and spokes model, since the player may defeat the eight robot masters in any order. Once they’re all defeated, the game switches into a linear sequence as Mega Man assaults Dr. Wily’s techno-castle and moves toward the game’s conclusion.

Mass Effect 2: The start and end of the game are linear strings of pearls, while the middle 80% is a giant pile of quests softly ordered by player skill and character level, with a central quest running through the middle using branching and story convergence. This hybrid structure is popular because it combines so many advantages. The designers get to script a careful introduction which introduces the story and game mechanics. During the softly ordered central portion, the player feels free and unconstrained. Finally, the game’s climax can be carefully authored for maximum effect.

Agency Problems

Imagine you’re a playwright on an experimental theater production. You get to write the lines for every character—except one. The protagonist is played by a random audience member who is pulled on stage and thrust into the role with no script or training.

Think that sounds hard?

Now imagine that this audience member is drunk. And he’s distracted because he’s texting on his cellphone. And he’s decided to amuse himself by deliberately interfering with the story. He randomly tosses insults at other cast members, steals objects off the stage, and doesn’t even show up for the climactic scene.

For a playwright, this is a writing nightmare. The fool on stage will disrupt his finely crafted turns of dialogue, contradict his characterization, and break his story. Game designers face this every day because games give players agency.

A well-constructed traditional story is a house of cards. Every character nuance, every word of dialogue, every shade of knowledge shared or held back plays a part in the intricate dance of narrative. Story events must chain-react in perfect succession and lead to a satisfying conclusion that speaks to a deathless theme. The writer painstakingly adjusts every word to achieve this result.

A game story pursues the same goal. But like the unfortunate playwright, it must also handle the fact that players can make choices. And whether they do it out of ignorance or malice, players can easily contradict or miss pieces of a story, toppling the author’s house of cards.

These agency problems fall into a few categories. Let’s look at them one by one.

Player–Character Motivation Alignment

Many agency problems appear because the player’s motivations are different from those of the character he controls.

The character wants to save the princess, make money, or survive a zombie outbreak. His motivations are inside the fiction of fantastical castles, criminal business dealings, or undead invasions. The player wants to entertain himself, see all the game content, and upgrade his abilities. His motivations are in the real world of social status, entertainment dollars, and game mechanics. When these two motivations point in different directions, the player will take actions that break the narrative. I call this desk jumping.

Note

DESK JUMPING is when the player takes an action that the player character would never take because their motivations are different.

The name comes from a situation I found in the spy thriller RPG Deus Ex. In Deus Ex, the player is a super-spy working for a secret intergovernmental organization. He can explore his agency’s secret office, get missions, talk with coworkers…and jump on their desks. Imagine James Bond dancing back and forth on his boss’s desk while they discuss a risky mission. It’s stupid and nonsensical. But the player will do it because it is funny. The character’s motivation is to get his mission, but the player’s motivation is to create humor. The motivations don’t align, so the player jumps on the boss’s desk, and the fiction falls apart.

Players desk-jump for many reasons. They want to explore the limits of the simulation, consume content, acquire stuff, achieve difficult goals, impress friends, and see pyrotechnics. I’ve seen players attack allies, systematically rob innocents (while playing as a good character), attempt to kill every single guard in the palace just to see if they can, or pile up oil barrels in the town square and light them off to try to get a big bang.

Consider the player’s motivation to explore game systems. The supernatural crime shooter The Darkness starts the player in front of a wounded ally who is delivering a long dialogue sequence. When I played this game, I didn’t listen to the speech. Instead, I shot the ally, just to see if it would work. It’s not that I hated him and wanted to kill him—my motivation wasn’t inside the fiction at all. Rather, I was exploring the limits of the game mechanics. I wanted to answer the question, “How did the designers deal with this?” In a mechanics-driven experience, this is healthy, since exploring systems is a major driver of meaning. But these mechanics had a fiction layer wrapped around them. And within that fiction layer, shooting the ally didn’t make sense. He died, and I missed most of his dialogue, and the hero’s good-guy characterization fell apart.

Sometimes desk jumping can be almost involuntary. In Grand Theft Auto IV, the protagonist, Niko Bellic, is trying to escape a violent past as a soldier in the Bosnian War. The game spends hours building up to a critical narrative decision at which Niko either murders an old enemy out of hate or lets him go. With this decision, the core of Niko’s character and the moral of the narrative hang in the balance. Does Niko discipline himself and become a peaceful man, or fall back into his vengeful ways? Do evil and hate win out in the world, or can a broken man heal and become good? It’s a poignant moment.

Except that by this time in the game, Niko has murdered hundreds of people, many of them innocent. Grand Theft Auto IV’s game mechanics design encourages the player to kill dozens of police officers and drive over crowds of pedestrians just for the hell of it. Niko likely crushed a few old ladies just minutes before, on his way to meet his old nemesis. And now he’s hemming and hawing over whether to kill one person. The player’s motivation has been to kill lots of people for fun, while the character’s motivation is not to kill. The result is nonsense.

There are a number of ways to solve desk-jumping problems. Let’s look at each of them.

Note

Disallowing desk jumping works, but weakens players’ engagement by destroying their belief in the honesty of the game’s mechanics.

In Deus Ex, the designers could have turned off the jumping ability inside the office, or placed invisible blockers over desks so that they cannot be jumped upon. The problem with this is that players quickly sense the artificiality of the devices used to control them. The game is no longer being true to its own systems—it is cheating within its own ruleset to get an arbitrary result the designer wanted. Faced with this, players stop thinking about what the mechanics allow, and start thinking about what the designer wants them to do. The narrative remains inviolate on the screen, but the player’s thought process of exploring the game mechanics collapses because the game mechanics aren’t honest and consistent.

When it is fictionally justified, however, disallowing desk jumping works exceptionally well. For example, Valve’s Portal has been lauded for its storytelling, but it doesn’t actually solve any of the thorny storytelling problems in games. Rather, it avoids them entirely through clever story construction. The only nonplayer character in Portal is GLaDOS, a computer AI who speaks to the player exclusively through the intercom; the game has no other human characters. The player character is trapped in a series of white-walled, nearly empty test chambers in an underground science facility. The only tool she finds is a portal-creating gun.

Portal’s world is so small and contained that it naturally disallows any player action which would break the fiction. The hero can’t tell other characters strange things or jump on their heads because the only other character is a disembodied computer voice. She can’t blow holes in the wall because she doesn’t have explosives. She could refuse to proceed, but even this wouldn’t bother the AI on the intercom, because an AI can wait forever. There is no temptation to desk-jump because this story involves no desks.

Similar tricks have been used by many other games. BioShock takes place in a collapsing underwater city—a perfectly enclosed, isolated environment, similar to Portal’s test chambers. You can’t wander outside the level because much of the city is locked down and flooded. You can’t blow holes in the walls because they’re made of reinforced steel designed to withstand crushing ocean pressures. You can’t talk to the locals because they’re all violently insane. The fiction naturally disallows most things that the game systems can’t handle. In games set in realistic cities, exploration must be disallowed by the use of nonsensical locked doors and other blockages, and communication with strangers must be arbitrarily disallowed in the interface.

Note

We can ignore desk jumping by letting players do it while not acknowledging it in any way. This makes desk jumping less appealing.

Valve used this solution in Half-Life 2. When you shoot the player’s companion character, nothing happens. She isn’t invincible; the bullets just never hit her. There is no blood, no animation, nothing.

Ignoring is, where possible, often better than disallowing or punishing because the player feels less controlled, and the behavior stops quickly when the player gets no interesting reaction. Players understand that game mechanics have limits; it’s often better to make those limits simple, obvious, and dull than it is to try to camouflage them.

Players desk-jump for humor, mechanics exploration, and power upgrades. These aren’t unhealthy motivations. Sometimes it’s better to embrace the actions players are taking and spin the narrative around them.

For example, in Deus Ex, while exploring the spy office, the player can go into the women’s restroom. If he does, he is confronted by a shocked female coworker and later told off by his boss. It’s a funny response to a funny action by the player.

Some games positively revel in desk jumping. In Duke Nukem Forever, the player’s traditional health bar is replaced with an Ego bar, which expands when Duke plays pinball, lifts weights, throws basketballs around, and harasses strippers. This reinforces Duke’s over-the-top macho characterization.

The key problem with incorporating desk jumping is that it can lead to an ever-expanding scope of what must be incorporated. If the player jumps on the boss’s desk, and the boss says, “Get off my desk,” we’ve incorporated desk jumping. But what if the player keeps jumping on the desk? Does the boss have more dialogue asking the player to get off his desk? Does he eventually take physical action against the player? What about after that? Does the player eventually get court-martialed and thrown in jail because of an office shootout that started with a disagreement over his jumping on his boss’s desk? A player who is motivated to explore game systems or create humor can always keep escalating. To solve this, it’s best to seek ways to incorporate desk jumping in a closed and complete way, as with Duke Nukem Forever.

Note

The best solution to desk jumping is to design the game so that players’ motivations and abilities line up with those of their character.

We can always deal with desk jumping. But the best way to handle it is for players to never want to do it in the first place.

For example, in Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, it is possible to desk-jump. The player can refuse to complete objectives, refuse to fire, or try to block allies or catch them spawning. Yet, this rarely happens in this game because the high-energy combat is so fast-paced, insistent, and compelling. When tanks are exploding, commanders are urging troops forward, and enemies are swarming like flies, the player gets so keyed up that the impulse to fight overrides the impulse to act like an idiot.

The player’s motivation doesn’t have to be the same in source as their character—only in goal. In Call of Duty, the character is motivated by honor, loyalty, and fear, while the player is motivated by energy and entertainment. It doesn’t matter that these motivations are very different, though, since they lead to the same actions: fighting enemies as hard as possible.

This kind of motivation alignment is very difficult to achieve consistently because it crosses the bounds between fiction and narrative. Not only do we have to instill in the player a burning desire to achieve some goal, but that desire has to be mirrored in the character. It’s one of the key reasons we have to design fiction and mechanics as a unified whole, instead of building them separately and duct-taping them together.

The Human Interaction Problem

Traditional stories are built from character interaction. Characters betray, demand, suggest, declare, debate, and dialogue their way through a series of emotional turns that constitute a story. This applies to nearly all stories, not just dramas. Even the most pyrotechnic of action films and the bloodiest of horror stories fill most of their time with people talking.

This is a problem for game designers, since there is currently no way to do rich human interaction with a computer. Buttons, joysticks, and simple motion sensors aren’t enough to allow people to express thoughts and feelings to a machine. Furthermore, even if players could express themselves to the machine, the machine would not be able to respond in kind because we have no technology that can simulate a human mind.

To make human interaction work in games, we can use a set of tricks that get around the limitations of the medium.

Note

We can set up the fiction so that there is naturally no way to interact directly with humanlike characters.

The cleanest solution to the human interaction problem is to not do human interaction. Consider that one of the reasons world and emergent story tools work so well in games is that they don’t require the game to handle players interacting with a character.

This doesn’t mean there can’t be characters, or that people can’t talk. You can interact with stupid or insane characters. You can interact with quasi-human computers or inhuman AIs. You can observe other humans interacting with one another, or find a tape of a conversation that happened earlier. The only restriction is that the player character can’t ever engage in a two-way interaction with a sane, conscious, coherent, humanlike character.

In BioShock, for example, sane characters only ever speak to the player over a radio or through unbreakable glass. The characters who can be confronted face to face are all violently insane. You can watch these madmen as they go about their broken lives and listen to their deranged muttering, but this works because you’re not interacting, just watching as they follow a predefined script. As soon as you try to interact, they fly into a murderous rage that the computer can simulate without trouble.

Note

DIALOGUE TREES can handle human interaction by predefining a list of actions players can take and matching responses from other characters.

Some games model interpersonal interaction with dialogue trees that allow the player to choose among a number of social interactions their character can perform. This works because the game designers can author every side of every interaction. There is no need to simulate anything.

The downside is that the player only has a handful of choices instead of the near-infinite variety available in real life.

The actions players can take in games are usually all about moving, collecting, pushing, jumping, and shooting. It is possible to use these kinds of interactions to express human interactions.

One example is a situation in which the player is forced to choose between killing two different characters. In Grand Theft Auto IV, the protagonist is presented with an old enemy tied up on the ground and given an opportunity to kill him. The player can choose to either shoot the defenseless man or walk away. Both actions are expressed through controls that are used throughout the game: shooting and walking. But here, these actions are used to drive a predefined plot branch instead of a normal piece of gameplay.

Such interactions are fundamentally the same as dialogue trees since the player’s options and the world’s responses are all predefined. The only difference is that they express their choice with normal game actions instead of a special dialogue tree interface. This can help preserve flow because it doesn’t break the player’s natural control rhythm. It also avoids the interface complexity of real dialogue trees.

In Dungeons & Dragons, the Dungeon Master plays the role of every nonplayer character in the game. He speaks for them and decides how they’ll respond to any action the players take. There doesn’t need to be a limit on what the players can do because, being a real person, the Dungeon Master can understand and respond to anything.

Real people can create remarkable stories together when they’re motivated to do so. The trouble with this method is aligning player motivation with character motivation. It means motivating every player to properly play their role in the game narrative, which is exceptionally difficult. It works in face-to-face games played among friends because social pressure motivates people to participate in good faith. In video games, with anonymous strangers, or in competitive games, it’s difficult to impossible to arrange players’ motivations so that sustained, rich role playing can happen.

Case Study: Fallout 3

Let’s examine a game-driven narrative experience and break down the narrative tools used to generate it. First, I’ll tell you a story that happened to me when I played Bethesda Game Studios’ 2008 post-apocalyptic RPG Fallout 3. After that, I’ll break it down.

The game begins with the player character’s birth in Vault 101. Built underground centuries ago, the Vault’s purpose is to protect its inhabitants from nuclear holocaust. This story picks up as the player character leaves the Vault for the first time at age 19.

My Story

The landscape was a windblown expanse dotted with dead trees, smashed cars, and human bones. With the Vault door closed behind me, I had nowhere to go but forward.

Within minutes I encountered a tiny settlement called Megaton. While wandering through town, I encountered a store called Craterside Supply. Like every other structure in Megaton, the building was no more than tacked-together sheet metal and junkyard scrap. It was only identifiable by the name scrawled in white paint beside the front door.

The inside didn’t look much better than the outside. Dust hung in the air, glowing yellow under the arc-sodium lighting, while ramshackle shelves lined the walls. A young woman in grubby blue coveralls swept the floor behind the counter, her flame-red hair pulled back into a messy ponytail. I approached her.

“Hey!” she said. “I hear you’re that stray from the Vault! I haven’t seen one of you for years! Good to meet you!” Her voice seemed to pitch higher and higher with every syllable. After the dour Wasteland, her enthusiasm was almost unnerving. “I’m Moira Brown. I run Craterside Supply, but what I really do is mostly tinkering and research.” She paused for a moment. “Say, I’m working on a book about the Wasteland—it’d be great to have the Foreword by a Vault dweller. Help me out, would you?”

She seemed friendly, and I needed friends. “Sure,” I said, “I’ve got plenty to say about life in the Vault.”

“Great!” she replied. “Just tell me what it’s like to live underground all your life, or to come outside for the first time, or whatever strikes your fancy!”

I thought she might be playing with me, so I decided to play back. “This ‘Outside’ place is amazing,” I said. “In the main room, I can’t even see the ceiling!”

“Hah!” said Moira. “Yeah, you wouldn’t imagine how hard it is to replace that big lightbulb up there, too! That’s great for a Foreword—open with a joke and all that. That’ll be good for the book. In fact, want to help with the research? I can pay you, and it’ll be fun!”

“What’s this book you’re working on?” I asked.

“Well, it’s a dangerous place out there in the Wastes, right? People could really use a compilation of good advice. Like a Wasteland Survival Guide! For that, I need an assistant to test my theories. I wouldn’t want anyone to get hurt because of a mistake. Nobody’s ever happy when that happens. No…Then they just yell a lot. At me. With mean, mean words.”

I considered this. “Sounds like a great idea!” I said. “I can’t wait to help! What are you looking for?”

“Well, food and medicine. Everyone needs them once in a while, right? So they need a good place to find them! There’s an old Super-Duper Mart not far from here. I need to know if a place like that still has any food or medicine left in it.”

I agreed and said goodbye. An hour out of the Vault, and already I’m Moira Brown’s survival guinea pig.

Once outside the town gates, I followed my compass toward the Super-Duper Mart. I soon crested a hill and found the husk of Washington, DC, laid out in front of me. Shattered buildings stretched away to the horizon, forming a jagged border against the yellow sky. I trudged toward them.

I found the Super-Duper Mart on the outskirts of town. Whoever architected it must have lacked in either creativity or money, because it was no more than a giant concrete shoebox, identifiable only by the huge block-letter sign looming over the parking lot.

As I entered the parking lot, I heard the boom of a big hunting gun alternating with the pakpakpak of an assault rifle. I rounded a corner and found a Wasteland raider battling it out with a man in an ancient leather coat. “What’s wrong? Can’t stand the sight of your own blood?” screamed the man in leather. They were his last words. The raider shot him down with a burst from the assault rifle and he fell, gurgling. Then she turned on me.

As with most raiders, this one had dressed to impress. She sported a tight black jumpsuit covered in spikes, a double Mohawk, and thick eyeliner that lent a demonic quality to her face.

She fired with her assault rifle. I fired back with my pistol. I must have hit her in the arm, because she dropped her weapon. I kept firing as she rushed to pick it up and take cover behind an ancient car.

Then she opened up, this time from behind the car. I was caught in the open and took several hits. It looked bad—my pistol wasn’t powerful enough for me to trade blows with her assault rifle like this.

Just as I was getting desperate, I heard a boom from behind me. I turned to find a leather-clad woman firing at the raider with a huge rifle. She fired once more, and the raider fell.

I approached the dead raider and stripped her of everything she carried, including her assault rifle and ammunition. I even took her spiky clothes. They weren’t my style, but I thought I might sell them later.

Just as I finished looting the corpse, an explosion went off right beside me and my vision filled with white. Coming to, I realized what had happened. The car the raider had used as cover had begun to burn when it was hit by stray shots. It had continued burning as I looted her corpse, and only exploded just now.

The explosion had crippled my right leg and left arm. I couldn’t aim or move properly like this. I looked through my pack and found a Stimpak healing device. The chemicals flowed through my veins and healed my limbs enough to make them usable again. I chugged a Nuka-Cola to shore up my strength.

As I approached the Super-Duper Mart’s front entrance, I noticed three corpses strung up in front of the store, twisted into grotesque poses. These weren’t just casual murder victims—they were raider trophies on display. It seemed that the raider in the parking lot wasn’t just passing through. The Super-Duper Mart was a raider base.

I reloaded my pistol and entered the building.

The store was dark inside. Sunlight struggled to penetrate windows caked with centuries of grime. A few of the fluorescent ceiling lights were still burning, forming yellow blobs of light in the choking dust. Shopping carts were scattered randomly over the floor, and the shelves displayed rows and rows of nothing.

I saw no one from my position at the door, but I knew they must be there. I crept into the room, using the dark to stay hidden. As I edged up to a checkout counter, I noticed a lone raider patrolling across the tops of the aisles, weapon in hand.

I snuck closer, took careful aim, and fired my pistol. The shot skimmed past the raider’s head and thudded into the rear wall of the store. Return fire erupted from all around as raiders emerged from the woodwork, alerted by my attack. I retreated back to the checkout counter as bullets pinged around me. I found targets and fired, killing several raiders.

Two attackers approached from the left. One fell quickly to my pistol. The other aimed a gigantic rifle at me and fired, hitting the counter in front of me. I threw four rounds at his chest. One of them hit, but he kept coming, his rifle making great crashing sounds as it tried to tear off my head.

I retreated behind a pillar, desperate. Looking through my inventory, I found the assault rifle I stole from the spike-wearing raider in the parking lot. I readied it and waited. As the rifleman came into view, I put eight rounds into him in one long burst. He fell with a clipped scream.

The store went quiet. It seemed the fight was over, so I began scavenging. Dead raiders yielded armor and ammunition. I grabbed the hunting rifle off my last victim. Vending machines produced Nuka-Cola. Exploring the bathrooms, I found mattresses and drugs on the floors. It seemed this was where the raiders had been sleeping. A fridge yielded an assortment of food—the first thing Moira wanted me to find.

I proceeded into the back of the store to find the medicine Moira wanted. More unfortunate dead Wastelanders hung from the ceiling. The last was nailed to the wall in a vaguely Christlike pose. Like many of the others, he was headless.

As I studied him, I heard a burst of automatic weapons fire. I saw my blood and heard my cries of pain as the bullets hit me. Turning, I saw my ambusher. It was a raider with an assault rifle, wearing a motorcycle helmet with antlers nailed to the sides. He kept shooting, wounding my left arm. I stumbled back, firing blindly with my pistol. His next burst shattered my leg just as I dropped behind the cover of the pharmacy counter.

I looked through my pack and noticed a frag grenade. I stood up and tossed it. It landed at the antlered madman’s feet and exploded, separating his legs at the knees and launching him into the air.

The store quieted again.

I repaired my arm with my last Stimpak and began scavenging. I picked the locks on some ammunition cases, taking bullets, grenades, and improvised mines. On various shelves I found machine parts, scraps of food, and a book called Tales of a Junktown Jerky Vendor.

Trying to get into the pharmacy’s back room, I found myself blocked by a door that was too advanced for my rudimentary lockpicking skills. Searching around, I found a key for the pharmacy in a metal box some distance away. I returned and used it to open the door.

The pharmacy storage room was filled with rows of broken-down shelving. Most of it was covered with junk, but I did find darts, more grenades, liquor, a pressure cooker, and a miniature nuclear bomb. I also found the medical supplies Moira wanted to know about. I used one of the Stimpaks to heal my wounded leg.

As I left the pharmacy, I heard a voice over the store P.A. system. “We’re back. Somebody open up the…Hang on, something ain’t right here.” Raiders were entering the store from the front door, and I was trapped at the back.

It was a hard fight, but I made it. By the time I got back to Megaton, the sky had faded to a dusty blue. Moira was cheery as always. “Huh. Did you know that the human body can survive without the stomach or spleen?” she enthused. “Oh, what’s up?”

Breakdown

This story is a particular experience that a player can have in Fallout 3. It will never happen exactly the same way to two players. Still, it can be understood as a story. It has pacing, exposition, a beginning, and an end.

Fallout 3 uses many different narrative tools. World story is everywhere, in the landscape, the architecture, and the mise-en-scène of junk, loot, and corpses. Other parts of the story, such as Moira’s dialogue, are hard-scripted. Still others, such as combat encounters, are soft-scripted.

The integrated story that the player experiences arises emergently from the interaction of scripts, game systems, and the player’s decisions. This emergence happens at all levels—on the micro level of individual motions and attacks, and on the macro level of quest choices and travel destinations. And because there are so many permutations, each player’s experience is unique.

My story opens through world narrative. The Capital Wasteland is a desiccated husk of a landscape. The scorched buildings and cars tell the history of a world cremated by nuclear fire. The town of Megaton tells its own world story through architecture: sheet-metal shacks and hand-painted signs speak of a hardscrabble life of extreme poverty. And people are characterized appearances, too: Moira Brown’s grungy coveralls and simple hairstyle mark a woman more interested in tinkering than popularity. You can tell she’s a geek.

But world story isn’t all that’s happening here. The player experiences this world story through his choices of where to go and what to look at. So as the player wanders the space, there are two story threads running: the backstory of nuclear war, and the emergent story of the player character walking around the Wasteland after escaping the Vault. One story goes, “This town was built by desperate people.” The other goes, “I walked into town and explored to my left.” The player experiences both stories at once, simultaneously feeling the emotional output of each.

Once I began talking with Moira, the game switched from exploratory world narrative to a dialogue tree. All of my words were chosen from lists of speech options, and Moira’s responses were all scripted.

To avoid the infinite story branching problem, Fallout 3’s dialogue trees loop back on themselves often. For example, every time you greet Moira, you get the same list of dialogue options, each leading to a different topic: purchasing gear, purchasing furniture for the player’s home, local gossip, repairing objects, any quests in progress, and so on. After each topic resolves, the dialogue returns to the root topic list. So the dialogue tree itself is arranged in a hub-and-spokes content ordering structure.

The approach to the Super-Duper Mart created a sense of anticipation of the challenge ahead. This part of the story wasn’t in any script, but it was implied by the geometry of the world.

My encounter with the raiders and leather-clad hunters outside the Super-Duper Mart was an interesting convergence of narrative tools. The raiders were scripted to be there and will always appear in the same places. The hunters, however, were not part of any script. Hunters appear randomly in the Wasteland throughout the entire game. In this case, they happened to show up just as I arrived at the Super-Duper Mart. The hunters and raiders, being mutually hostile, began fighting as soon as they saw one another, and this emergent fight was still going on as I arrived.

My introduction to this battle was hearing the hunter’s bravado (“What’s wrong? Can’t stand the sight of your own blood?”), and seeing it get cut short by the raider’s assault rifle. The madly brave hunter screaming his last threat as he dies is a poignant emotional exchange. What’s interesting about this is that it is not modeled in the game mechanics. It is an interpretation constructed apophenically in a player’s mind from randomized dialogue barks and straightforward combat interactions.

After the first hunter died, I was pinned down by assault rifle fire from a second raider. This short fight formed a miniature emergent story with its own emotional arc. Being pinned made me tense. After an unseen hunter saved my life, I was filled with relief and gratitude toward my savior. It almost seemed like she was saving me as an act of kindness, or killing to exact revenge for her murdered companion. Naturally, these interpretations are all pure apophenia, but they feel real and affect the player nonetheless.

The fighting inside the supermarket forms another mini-story. My stealthy entrance into the space is exposition. It gave me time to understand their situation before diving in. When raiders started coming out of the woodwork, the tension ratcheted up. It peaked as the rifle-wielding raider approached. This tension was finally resolved with the epiphany of remembering the assault rifle taken from the raider in the parking lot and the triumphal counterattack. This little arc is like a scene from an action movie, but instead of being authored by a designer, it emerged from the interaction of game systems, soft scripts, and player choices.

The final ambush from the antlered assault rifle foe was not scripted. His “ambush” was emergent and there was no real intent behind it in the artificial intelligence—he just happened to be left over after the main fight. But even though it wasn’t in the mechanics, apophenically, it seemed like this last mad survivor had laid a trap.

The antlers gave that final raider a special personality by labeling him. He isn’t just a raider; he’s the weird raider with the goofy antlers. This label makes it easier to construct a story about him. Labeling is one area that Fallout 3 could have improved. Most characters are just nondescript raiders. Had they had more identity—crazy doctor, bartender, master, slave—players would have been able to construct better stories about them.

The Goofy Undertone

The world of Fallout 3 has a strong undertone of goofiness: Moira’s overwhelming enthusiasm, raiders with antlered helmets, and so on. These humorous juxtapositions are essential. Had the game been purely about surviving in a desperate, dead world, the emotional heaviness would have been too much for most players. Occasional absurdities lighten that emotional load.

Absurdity also helps justify less realistic parts of the game. For example, Fallout 3’s goofy vision of nuclear radiation permits it to throw all sorts of strange beasts at the player, from giant flies to 30-foot-tall humanoid behemoths. Had the radiation been modeled realistically, none of this would have been possible.

Finally, the unserious undertone reduces the impact of the inevitable logical absurdities in the game’s emergent stories. For example, I once walked up behind a caravan guard and shot him three times in the back of the head. He turned, scowled, and said, “I thought I heard something!” Instead of feeling wrong, this moment just felt funny.

Content Ordering

The content is ordered by both scripting and world geometry. For example, the player must pass through the parking lot before going inside. Once inside, he must pass through the main room before experiencing the pharmacy. Finally, the raiders coming in the doorway are scripted to appear only after the player has explored the pharmacy.

The player can leave and return to the quest at any time. He might do half of it, walk away, and come back 20 hours of play later to finish it up. This creates a vast number of possible paths through the game, as the player juggles many different quests.

Pacing

The pacing of this story is irregularly spiky. Tense moments of combat fall between longer periods of dialogue, exploration, healing, and scavenging. This mixture keeps players engaged without exhausting them.