Introduction

The World Wide Web continues to evolve, growing in scope and complexity, with new technologies popping up every year to make the Web look and work better. Even people building personal Web sites now use various programming languages and server technologies to dish up content. Throughout its history, Dreamweaver has managed to keep pace with this changing technological landscape with each new version.

Dreamweaver CS3 is no exception: It’s capable of working with more technologies than any previous version. Whether you’re creating database-enabled PHP Pages, adding your favorite site’s XML-based news feeds directly to your home page, using Cascading Style Sheets for cutting-edge design effects, dipping into the dynamic world of JavaScript and AJAX, or simply sticking to straightforward HTML pages, Dreamweaver has just about all the tools you need.

Any enterprising designer can create Web pages, Cascading Style Sheets, and even JavaScript programs with a simple text editor. In fact, Dreamweaver CS3 provides powerful text-editing abilities for creating basic text files or complex database-driven Web pages. But why go to all that trouble when Dreamweaver’s visual page-building approach makes your job of creating beautiful and complex Web sites so much easier? Whether you’re new to building Web pages or a hard-core, hand-coding HTML jockey, Dreamweaver is a powerful tool that lets you build Web sites quickly and efficiently, without compromising the quality of your code.

What Dreamweaver Is All About

Dreamweaver is a complete Web site production and management tool. It works with Web technologies like HTML, XHTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

The enhancements in the latest version, in fact, make it easier than ever to design and lay out Web sites. In particular, revamped Cascading Style Sheet support lets you access the latest Web techniques for creating fast-loading, easily modified Web page designs; while the new “Spry” technology provides one-click access to complex, interactive layout options like drop-down menus. Dreamweaver also includes plenty of tools for managing Web sites once you’ve built them. You can check for broken links, use templates to streamline site-wide page changes, and reorganize your site in a flash with the program’s site management tools.

Note

Get used to the acronym CSS, which you’ll encounter frequently in this book. It stands for Cascading Style Sheets, a formatting language used to design HTML Web pages. Dreamweaver CS3 continues to integrate advanced CSS creation, testing, and editing tools into Dreamweaver.

It’s also a serious tool for creating dynamic (database-driven) Web sites. You can now turn your company’s database of products into an easily updated online catalog—or turn that cherished recipe collection into an online culinary resource for an adoring public. You can even create Web pages for updating and deleting database records, meanwhile keeping designated areas of your site secure from unauthorized visitors. Best of all, Dreamweaver CS3 does the programming for you.

If you’ve never used Dreamweaver before, but have already built one or more Web sites, you won’t have to start from scratch. Dreamweaver happily opens Web pages and Web sites that were created in other programs without destroying any of your carefully handcrafted code.

Why Dreamweaver?

There are other Web design programs—dozens of them, in fact. But Dreamweaver has become one of the leading programs thanks to key benefits like these:

Visual page building. If you’ve spent any time using a text editor to punch out the HTML code for your Web pages, you know the tedium involved in adding even a simple item like a photograph to a Web page. When your boss asks you to add her photo to the company home page, you launch your trusty text editor and type something like this: <img src="images/staff/bigcheese.gif” width="100” height="150” alt="The Boss">.

Not only is this approach prone to typos, but it also separates you from what you want the page to look like.

Dreamweaver, on the other hand, takes a visual approach to building Web pages. If you put an image on your page, Dreamweaver shows you the picture on the screen. As in a word processor, which displays documents onscreen as they look when printed, Dreamweaver provides a very close approximation of what your Web page will look like in a Web browser.

Complex interactivity, simply. You’ve probably seen Web pages where an image (on a navigation bar, for example) lights up or changes appearance when you move your mouse over it.

Dynamic effects like this—mouse rollovers, alert boxes, and navigational popup menus—usually require programming in JavaScript, a programming language that most Web browsers understand. While JavaScript can do amazing things, it requires time and practice to learn.

Dreamweaver CS3 introduces an easy to use and innovative JavaScript-based technology called Spry. With Spry, you can easily create interactive, drop-down menus (Chapter 5), add advanced layout elements like tabbed panels (Chapter 12), and add sophisticated form validation to prevent visitors to your site from submitting forms with the proper information (Chapter 11).

Roundtrip code. Every now and then, even in Dreamweaver, you may sometimes want to put aside the WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) view and look at the underlying HTML code of a page. You may feel more comfortable creating some of your HTML by hand, for example, or you may want to tweak the HTML that Dreamweaver produces.

Adobe realized that many professional Web developers still do a lot of work “in the trenches,” typing HTML code by hand. In Dreamweaver, you can edit the raw HTML to your heart’s content. Switching back and forth between the visual mode—called Design view—and Code view is seamless and, best of all, nonde-structive. Unlike many visual Web page programs, where making a change in the WYSIWYG mode stomps all over the underlying HTML code, Dreamweaver respects hand-typed code and doesn’t try to rewrite it (unless you ask it to).

In addition, Dreamweaver can open many other types of files commonly used in Web sites, such as external JavaScript files (.js files), so you don’t have to switch to another program to work on them.

See Chapter 10 to learn more about how Dreamweaver handles writing and editing code.

Site management tools. Rarely will you build just a single Web page. More often, you’ll be creating and editing pages that work together to form part of a Web site. Or you may be building an entire Web site from scratch.

Either way, Dreamweaver’s site management tools make your job of dealing with site development easier. From managing links, images, pages, and other media to working with a team of people and moving your site onto a Web server, Dreamweaver automates many of the routine tasks every Webmaster faces. Part 4 of this book looks at how Dreamweaver can help you build and maintain Web sites.

Database-driven Web sites. Data makes the world go round. Whether you’re a human-resource records manager or a high school teacher, you probably keep track of a lot of information. Today, companies and individuals store reams of information in database systems like Microsoft Access or Oracle 10g. Dreamweaver CS3 can help you bring that information to life on the Web without having to learn a lot of programming along the way. From accessing information—such as the latest items in your company’s product catalog—to updating and editing data-bases online, Dreamweaver CS3 can help you build database-driven Web sites. Part 6 of this book offers a gentle introduction to building dynamic Web sites.

Have it your way. As if Dreamweaver didn’t have enough going for it, the engineers at Adobe have created a software product that is completely customizable, or, as they call it, extensible. Anyone can add to or change the menus, commands, objects, and windows in the program.

Suppose, for example, that you hardly ever use any of the commands in the Edit menu. By editing one text file in the Dreamweaver Configuration folder, you can get rid of any unwanted menu items—or even add new commands of your own creation. This incredible flexibility lets you customize the program to fit your work methods, and even add features that Adobe’s programmers never imagined. Best of all, the Adobe Exchange Web site includes hundreds of free and commercial extensions to download and add to Dreamweaver. See Chapter 21 for details.

Part of the Creative Suite. Since Adobe purchased Macromedia (the original creator of Dreamweaver), Web designers now have access to a much larger family of design tools including Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. Ultimately all of these Adobe programs will work together seamlessly and share a common appearance. Dreamweaver CS3 hasn’t yet adopted the look of an Adobe application, but it does include some useful integrations with the Adobe universe: You can now paste images from Photoshop directly into Dreamweaver (Chapter 6), and test your page designs in various cell phone models using Adobe’s Device Central product (Chapter 17).

What’s New in Dreamweaver CS3

If you’ve never used Dreamweaver before, see Chapter 1 for a welcome and the grand tour. If you’re upgrading from Dreamweaver 8 or some other version, you’ll find that Dreamweaver CS3 offers a host of new features aimed at both the novice Web designer and the seasoned HTML guru.

CSS power. Dreamweaver CS3 adds significant improvements to the program’s already impressive Cascading Style Sheet tools. The program improves on Dreamweaver 8’s already excellent display of complex CSS designs. Now, even as you use cutting-edge CSS techniques to design your pages, Dreamweaver’s visual Design view provides near WYSIWYG—what you see is what you get— editing power. In addition, Dreamweaver CS3 introduces new tools to effectively managing a site’s ever growing list of styles (the powerful design instructions that lay at the heart of CSS). You can quickly move styles between style sheets, rename styles, and convert old-school inline styles to the more efficient external style sheet. In addition, Dreamweaver includes new CSS layouts to help jumpstart your page designs, as well as a diagnostic tool called the “Browser Compatiblity” tool to help make sure your CSS works across different browsers.

Photoshop integration. If you’re a Photoshop user, Dreamweaver CS3 can help you work faster. Dreamweaver adds integrated support for the world’s pre-eminent graphics software. In Photoshop CS3 you can select a single layer (separate virtual canvasses used to build complex images); a slice (a selection of an image that you want to export as a separate Web graphic); or even draw a marquee around one area of a document and copy all layers in that section. You can then copy that selection, switch to a Dreamweaver document, and paste away. (Or you can skip all of these steps and just drag a PSD file directly onto a Dreamweaver page.)

Dreamweaver’s new image optimization window lets you apply file compression settings directly in Dreamweaver (great for creating slim-sized graphics that appear in Web browsers more quickly). Even better, without leaving Dreamweaver, you can launch Photoshop and open the original image file for editing. After making any changes you want in Photoshop, copy the layer, the slice, or the portion of the Photoshop file you want, and then paste the new, edited image back into Dreamweaver (thereby replacing the older image). Dreamweaver remembers all the optimization settings you previously applied (including the optimized file’s name), making edits fast and painless.

Active pages made easy. The most glamorous new addition to the program is a set of tools for adding dynamic layout elements and visual effects to your Web pages. Based on the “Spry Framework” (a collection of JavaScript programs developed by Adobe), these new features make it easy to add pop-up navigational menus, validate HTML forms, include complex, animated, visual effects, and add interactive data tables. The Spry Menu Bar, for example, lets you quickly and easily add a pop-up navigational menu to your site—without you having to learn all the messy JavaScript and CSS to make it happen.

In addition, Spry Form Validation widgets let you verify entries in a Web form before your site visitors try to submit the form. So, for example, you can make sure dates are properly formatted. (This widget provides a much more powerful solution than the tired, old “Validate Form” behavior that has shipped with Dreamweaver for years). The Spry Data Set feature lets you take data from an XML file and display it in a table. People viewing the Web page can sort the table by clicking column headers and even see detailed information about one item inside a table cell—all without ever requesting a fresh page from the Web server. And that’s just a quick preview of what you get thanks to the new Spry tools; Chapter 12 has the full story.

Souped-up speed. As with most updated software, Dreamweaver CS3 sports under-the-hood enhancements like better performance, more accurate display of CSS designs, and fixes to bugs that were in Dreamweaver 8. And, for you “I like to own the latest and greatest Apple computer” people, Dreamweaver CS3 has been rewritten to run natively (translation: faster) on the new Intel Macs.

Note

Adobe occasionally issues updates to Dreamweaver. To make sure you’re using the latest version, visit the Adobe Web site at www.adobe.com/products/dreamweaver/.

HTML, XHTML, and CSS 101

Underneath the hood of any Web page—whether it’s your uncle’s “Check out this summer’s fishin’” page or the home page of a billion-dollar online retailer—is nothing more than line after line of ordinary typed text. With its use of simple commands called tags, HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is still at the heart of most of the Web.

The HTML code that creates a Web page can be as simple as this:

<html> <head> <title>Hey, I am the title of this Web page.</title> </head> <body> <p>Hey, I am some body text on this Web page.</p> </body> </html>

While it may not be exciting, the HTML shown here is all you need to make an actual Web page.

Of Tags and Properties

In the example above—and, indeed, in the HTML code of any Web page you examine—you’ll notice that most commands appear in pairs that surround a block of text or other commands.

These bracketed commands constitute the “markup” part of the Hypertext Markup Language and are called tags. Sandwiched between brackets, tags are simply instructions that tell a Web browser how to display the Web page.

The starting tag of each pair tells the browser where the instruction begins, and the ending tag tells it where the instruction ends. An ending tag always includes a forward slash (/) after the first bracket symbol (<), which tells the browser that it is a closing tag.

Fortunately, Dreamweaver can generate all of these tags automatically. There’s no need for you to memorize or even type these commands (although many programmers still enjoy doing so for greater control). Behind the scenes, Dreamweaver’s all-consuming mission is to convert your visual designs into underlying codes like these:

The <html> tag appears once at the beginning of a Web page and again (with an added slash) at the end. This tag tells a Web browser that the information contained in this document is written in HTML, as opposed to some other language. All the contents of a page, including other tags, appear between the opening and closing <html> tags.

If you were to think of a Web page as a tree, the <html> tag would be its trunk. Springing from the trunk are two branches that represent the two main parts of any Web page: the head and the body.

The head of a Web page, surrounded by <head> 7 tags, contains the title of the page. It may also provide other, invisible information (such as search keywords) that browsers and Web search engines can exploit.

In addition, the head can contain information that the Web browser uses for displaying the Web page and adding interactivity. Cascading Style Sheet information, used for formatting text and other elements, may be defined in the head of the document (see Chapter 4). In addition, JavaScript scripts, functions, and variables can be declared in the head of the document. In fact, Dreamweaver’s new Spry widgets (Chapter 12) achieve their interactive effects with the help of JavaScript code stored in a page’s head.

The body of a Web page, as set apart by its surrounding <body> tags, contains all the information that appears inside a browser window—headlines, text, pictures, and so on.

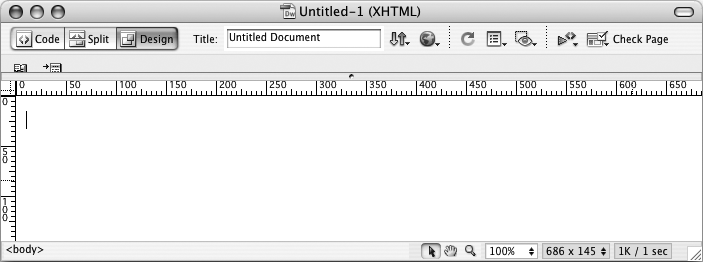

In Dreamweaver, the blank white portion of the document window represents the body area (see Figure I-1). It resembles the blank window of a word processing program.

Most of your work with Dreamweaver involves inserting and formatting text, pictures, and other objects in the body of the document. Many tags commonly used in Web pages appear within the <body> tag. Here are a few:

You can tell a Web browser where a paragraph of text begins with a <p> (opening paragraph tag), and where it ends with a </p> (closing paragraph tag).

The <strong> tag is used to emphasize text. If you surround some text with it and its partner tag, </strong>, you get boldface type. The HTML snippet <strong>Warning!</strong> would tell a Web browser to display the word “Warning!” in bold type on the screen.

The <a> tag, or anchor tag, creates a link (hyperlink) in a Web page. A link, of course, can lead anywhere on the Web. How do you tell the browser where the link should point? Simply give address instructions to the browser inside the <a> tags. For instance, you might type <a href=” http://www.missingmanuals.com/ “>Click here!</a>.

The browser knows that when your visitor clicks the words “Click here!” it should go to the Missing Manual Web site. The href part of the tag is called, in Dreamweaver, a property (you may also hear the term attribute), and the URL (the Uniform Resource Locator, or Web address) is the value. In this example, http://www.missingmanuals.com is the value of the href property.

Fortunately, Dreamweaver exempts you from having to type any of these codes and provides an easy-to-use window called the Property inspector for adding properties to your tags and other page elements. To create links the Dreamweaver way (read: the easy way), turn to Chapter 5.

XHTML, Too

Like any technology, HTML is showing its age. Although it’s served its purpose well, it’s always been a somewhat sloppy language. Among other things, it allows uppercase, lowercase, or mixed-case letters in tags (<body> and <BODY> are both correct, for example) and permits unclosed tags (so that you can use a single <p> tag without the closing </p> to create a paragraph). While this flexibility may make page writing easier, it also makes life more difficult for Web browsers, PDAs, and other technologies that must interact with data on the Web. Additionally, HTML doesn’t work with one of the hottest up-and-coming Internet languages: XML, or Extensible Markup Language (see What Is XML? for a quick intro to XML).

To keep pace with the times, an improved version of HTML called XHTML is finding its way into more and more Web sites. Once again, Dreamweaver CS3 is right on the cutting edge: it can create and work with XHTML files. If you understand only HTML, don’t worry—XHTML isn’t a revolutionary new language that takes years to learn. It’s basically HTML, but with somewhat stricter guidelines. For example, the HTML page code shown on HTML, XHTML, and CSS 101 would look like this in XHTML:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd"> <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <title>Hey, I am the title of this Web page.</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=iso 8859-1" /> </head> <body> <p>Hey, I am some body text on this Web page.</p> </body> </html>

Notice that everything below the <head> is exactly the same as the HTML page. The information that begins the page, however, is how the page identifies which standards it conforms to. In this case, it merely says that the page is using a particular brand of HTML, called XHTML, and more specifically a type of XHTML called Transitional 1.0. (Don’t worry—Dreamweaver automatically writes all of this code when you create a new XHTML page.)

As you can see, the real code used to make the page is much like HTML. To make an XHTML file comply with XML, however, there are a few strict rules to keep in mind:

Begin the page with a document-type declaration and a namespace. That’s the first few lines in the code above. They simply state what type of document the page is and point to files on the Web that contain definitions for this type of file.

Tags and tag attributes must be lowercase. Unlike in HTML, typing the tag <BODY> in an XHTML file is incorrect. It must be lowercase like this: <body>.

Quotation marks are required for tag attributes. For example, a link written like this: <a href=http://www.missingmanuals.com > is valid in HTML, but doesn’t work in XHTML. You have to enclose the value of the href property in quotes: <a href=”http://www.missingmanuals.com“>.

All tags (even empty tags) must be closed. To create a paragraph in XHTML, for example, you must begin with <p> and end with </p>. However, some tags don’t come in pairs. These tags, called empty tags, have no closing tag. The line break tag is one example. To close an empty tag, you must include a forward slash at the end of the tag, like this: <br />.

If all this seems a bit confusing, don’t worry. All these strict XHTML rules are built into Dreamweaver, so creating an XHTML page using Dreamweaver’s visual design tools won’t feel one bit different from creating an old-style HTML page. (For more information on creating an XHTML page in Dreamweaver, see Creating a Web Page.)

Adding Style with Cascading Style Sheets

HTML used to be the only language you needed to know. You could build pages with colorful text and graphics and make words jump out using different sizes, fonts, and colors. But today, you can’t add much visual sophistication to a site without Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). CSS is a formatting language used to make text look good, add sophisticated layout to pages, and basically add style to your site.

From now on, think of HTML as merely the language you use to give organization to a page. It helps identify and structure the stuff you want the world to know about. Tags like <h1>, <h2>, and <title> denote headlines and assign them relative importance: a heading 1 is more important than a heading 2. The <p> tag indicates a basic paragraph of information. Other tags provide further structural clues: for example, a <ul> tag identifies a bulleted list (to make a list of recipe ingredients more intelligible).

Cascading Style Sheets, on the other hand, add design flair to the highly structured HTML content, making it more beautiful and easier to read. Essentially, a CSS style is just a rule that tells a Web browser how to display a particular element on a page—for example, to make a <h1> tag appear 36 pixels tall, in the Verdana font and the color orange.

But CSS is more powerful than that. You can use it to add borders, change margins, and even control the exact placement of an element on a page.

If you want to be a Web designer, you need to get to know Cascading Style Sheets. You’ll learn more about this exciting technology throughout this book. In fact, it’s so important for current Web design, that this edition of Dreamweaver: The Missing Manual now includes expanded coverage and examples of CSS in most chapters.

The Very Basics

You’ll find very little jargon or nerd terminology in this book. You will, however, encounter a few terms and concepts that you’ll encounter frequently in your computing life:

Clicking. This book gives you three kinds of instructions that require you to use your computer’s mouse or trackpad. To click means to point the arrow cursor at something on the screen and then—without moving the cursor at all—press and release the clicker button on the mouse (or laptop trackpad). To double-click, of course, means to click twice in rapid succession, again without moving the cursor at all. And to drag means to move the cursor while holding down the button.

Keyboard shortcuts. Every time you take your hand off the keyboard to move the mouse, you lose time and potentially disrupt your creative flow. That’s why many experienced computer fans use keystroke combinations instead of menu commands wherever possible. Ctrl+B (⌘-B for Mac folks), for example, is a keyboard shortcut for boldface type in Dreamweaver (and most other programs).

When you see a shortcut like Ctrl+S (⌘-S), it’s telling you to hold down the Ctrl or ⌘key and, while it’s down, type the letter S, and then release both keys. (This command, by the way, saves changes to the current document.)

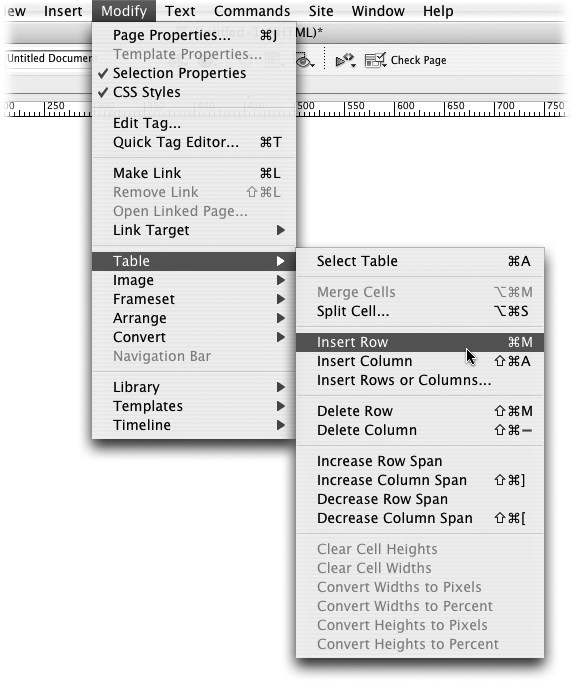

Choice is good. Dreamweaver frequently gives you several ways to trigger a particular command—by selecting a menu command, or by clicking a toolbar button, or by pressing a key combination, for example. Some people prefer the speed of keyboard shortcuts; others like the satisfaction of a visual command available in menus or toolbars. This book lists all the alternatives, but by no means are you expected to memorize all of them.

About This Book

Despite the many improvements in software over the years, one feature has grown consistently worse: documentation. Until version 4, Dreamweaver came with a printed manual. But since MX 2004, all you get is a Getting Started booklet. To get any real information, you need to delve into the program’s online help screens.

But even if you have no problem reading a help screen in one window as you work in another, something’s still missing. At times, the terse electronic help screens assume you already understand the discussion at hand, and hurriedly skip over important topics that require an in-depth presentation. In addition, you don’t always get an objective evaluation of the program’s features. Engineers often add technically sophisticated features to a program because they can, not because you need them. You shouldn’t have to waste your time learning features that don’t help you get your work done.

The purpose of this book, then, is to serve as the manual that should have been in the box. In this book’s pages, you’ll find step-by-step instructions for using every Dreamweaver feature, including those you may not even have quite understood, let alone mastered, such as Libraries, Layout view, Behaviors, Dreamweaver’s Dynamic Web site tools, and Dreamweaver CS3’s new Spry tools and CSS features. In addition, you’ll find clear evaluations of each feature that help you determine which ones are useful to you, as well as how and when to use them.

Note

This book periodically recommends other books, covering topics that are too specialized or tangential for a manual about using Dreamweaver. Careful readers may notice that not every one of these titles is published by Missing Manual parent O’Reilly Media. While we’re happy to mention other Missing Manuals and books in the O’Reilly family, if there’s a great book out there that doesn’t happen to be published by O’Reilly, we’ll still let you know about it.

Dreamweaver CS3: The Missing Manual is designed to accommodate readers at every technical level. The primary discussions are written for advanced-beginner or intermediate computer users. But if you’re new to building Web pages, special sidebar articles called “Up To Speed” provide the introductory information you need to understand the topic at hand. If you’re a Web veteran, on the other hand, keep your eye out for similar shaded boxes called “Power Users’ Clinic.” They offer more technical tips, tricks, and shortcuts for the experienced computer fan.

About → These → Arrows

Throughout this book, and throughout the Missing Manual series, you’ll find sentences like this one: “Open the System →Library →Fonts folder.” That’s shorthand for a much longer instruction that directs you to open three nested folders in sequence, like this: “On your hard drive, you’ll find a folder called System. Open that. Inside the System folder window is a folder called Library; double-click it to open it. Inside that folder is yet another one called Fonts. Double-click to open it, too.”

Similarly, this kind of arrow shorthand helps to simplify the business of choosing commands in menus, as shown in Figure I-2.

Macintosh and Windows

Dreamweaver CS3 works almost precisely the same way in its Macintosh and Windows versions. Every button in every dialog box is exactly the same; the software response to every command is identical. In this book, the illustrations have been given even-handed treatment, alternating between the various operating systems where Dreamweaver feels at home (Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Mac OS X).

One of the biggest differences between Mac and Windows software is the keystrokes, because the Ctrl key in Windows is the equivalent of the Macintosh ⌘key.

And the key labeled Alt on a PC (and on non-U.S. Macs) is the equivalent of the Option key on American Mac keyboards.

Whenever this book refers to a key combination, therefore, you’ll see the Windows keystroke listed first (with + symbols, as is customary in Windows documentation); the Macintosh keystroke follows in parentheses (with - symbols, in time honored Mac fashion). In other words, you might read, “The keyboard shortcut for saving a file is Ctrl+S (⌘-S).”

About the Outline

Dreamweaver CS3: The Missing Manual is divided into six parts, each containing several chapters:

Part 1, Building a Web Page, explores Dreamweaver’s interface and takes you through the basic steps of building a Web page. It explains how to add text and format it, how to link from one page to another, how to spice up your designs with graphics, and introduces you to Cascading Style Sheets.

Part 2, Building a Better Web Page, takes you deeper into Dreamweaver and provides in-depth CSS coverage. In addition, you’ll get step-by-step instructions for creating advanced page layouts, as well as advice on how to view and work with the underlying HTML code of a page.

Note

Previous versions of this book contained a chapter on HTML frames—a method of displaying several Web pages in a single Web browser window. This technique is going the way of the dodo bird. Since Dreamweaver CS3 has so many new and exciting features and this book’s already bursting at its seams (if we added any more pages, we’d have to issue a medical warning to those with bad backs), the frames chapter has been moved online. You can find it, free of charge, at www.sawmac.com/missing/dw8/appc.pdf

Part 3, Bringing Your Pages to Life, helps you add interactivity to your site. From using forms to collect information from your site’s visitors to adding interactive page widgets like tabbed interfaces with the new Spry framework, this section guides you through adding animation, multimedia, and other interactive effects with ease.

Part 4, Building a Web Site, covers the big picture: managing the pages and files in your Web site, testing links and pages, and moving your site onto a Web server connected to the Internet. And since you’re not always working solo, this section also covers features that let you work with a team of Web developers.

Part 5, Dreamweaver Power, shows you how to take full advantage of such time-saving features as Libraries, Templates, and History panel automation. It also covers Dreamweaver’s Extension Manager, a program that can add hundreds of new free and commercial features to the program.

Part 6, Dynamic Dreamweaver, presents a gentle introduction to the often confusing and complex world of database-driven Web sites. You’ll learn what you need to know to build a dynamic Web site; how to connect Dreamweaver to a database; and how to use Dreamweaver to build pages that can display database information as well as add, edit, and delete database records. The last chapter of this section covers the powerful XSLT tools for converting XML files (including RSS feeds) into browser-ready Web designs.

At the end of the book, two appendixes provide a list of Internet resources for additional Web design help and a menu-by-menu explanation of Dreamweaver CS3.

Living Examples

This book is designed to get your work onto the Web faster and more professionally; it’s only natural, then, that half the value of this book also lies on the Web.

As you read the book’s chapters, you’ll encounter a number of living examples—step-by-step tutorials that you can build yourself, using raw materials (like graphics and half-completed Web pages) that you can download from either www.sawmac.com/dwcs3/ or from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com. You might not gain very much from simply reading these step-by-step lessons while relaxing in your porch hammock. But if you take the time to work through them at the computer, you’ll discover that these tutorials give you unprecedented insight into the way professional designers build Web pages.

You’ll also find, in this book’s lessons, the URLs of the finished pages, so that you can compare your Dreamweaver work with the final result. In other words, you won’t just see pictures of Dreamweaver’s output in the pages of the book; you’ll find the actual, working Web pages on the Internet.

About MissingManuals.com

At www.missingmanuals.com, you’ll find articles, tips, and updates to Dreamweaver CS3: The Missing Manual. In fact, we invite and encourage you to submit such corrections and updates yourself. In an effort to keep the book as up to date and accurate as possible, each time we print more copies of this book, we’ll make any confirmed corrections you’ve suggested. We’ll also note such changes on the Web site, so that you can mark important corrections into your own copy of the book, if you like. (Click the book’s name, and then click the Errata link, to see the changes.)

In the meantime, we’d love to hear your own suggestions for new books in the Missing Manual line. There’s a place for that on the Web site, too, as well as a place to sign up for free email notification of new titles in the series.

Safari Enabled

When you see a Safari® Enabled icon on the cover of your favorite technology book, that means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-books. It’s a virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top tech books, cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at http://safari.oreilly.com.

Get Dreamweaver CS3: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.