You get up in the morning with the shades yanked down, after having collapsed under the covers at some indeterminate time past midnight (which followed several robotic hours of Facebook typing). Luckily, you’d set the coffee maker on a timer, so a quart of strong joe waits on the kitchen counter. Twelve ounces of that washes down a toasted bagel smeared with extra margarine and jelly, as you’re out the door on the way to a 45-minute car commute.

It’s just the beginning of a marathon bout of sitting.

Sound familiar? When you get to work it’s an elevator ride off to the cubicle, where you refill the to-go coffee mug with joe that already tastes old, and someone’s left an open box of donuts in convenient proximity. You write code until you’re cross-eyed, interspersed with two meetings where you sit on your behind listening to two marketing/admin guys who love to hear themselves pontificate.

At lunchtime, you take the elevator downstairs and walk half a block to Subway, where you buy a “healthy” tuna n’ cheese sub, which is almost the size of the baseball bat you used in Little League. Half of it is munched down before you get back to your cubicle and that C++ module you were supposed to finish by 5:30, which rolls around with an amazing sense of time squashed into a smaller space than you ever needed it to be.

A few times during the day, you join the crowd congregating in front of the vending machines (to which an entire work enclave has been devoted). The temptation to push a couple of buttons on this amazing invention and get something—chips (many varieties), a Pop-Tart, crackers and tuna salad (yup, they have those in vending machines)—is overwhelming. The lively sounds of conversation are interspersed with the ripping noise of little bags being opened.

You wanted to exercise, but... it’s back to the car commute and “dinner” (consisting of a Diet Pepsi and the rest of the sub while driving), when it dawns on you that you could not tell someone whether you actually walked in or physically sensed any sunlight that day. You get home, slump down onto a couch in the familiar sitting position, and, well, you feel like the bloody indefinable thing your big old cat, Hooch, who now eyes you with an inscrutable neutrality, dragged home that day.

Ditto the next day.

What’s wrong with this picture? Okay, so the implications of this narrative are pretty obvious. Hope I didn’t lay it on too thick. You probably spent most of the day as a “chair liver.”

The food you ate was “bad for you” (or simply not particularly good), and you didn’t take any opportunities to move your limbs around, beyond pumping your fist in the air during an online glimpse of ESPN SportsCenter. You failed to stand up or walk for a reasonable period of time. The sun, bestowing life on earth, has become a stranger.

It’s not your fault, you argue silently, with at least a little credibility. The work/commute schedule is crazy. You’re lucky enough to have any job that pays pretty well.

The messages your body undoubtedly sends you, however, roughly translated as I feel like crap, probably indicate that you’re not really designed to live this way. In fact, a bunch of scientists, fitness experts, philosophers, economists, anthropologists, medical doctors, and overall outside-the-box thinkers have come up with the sensible hypothesis that we are designed for our ancestors’ way of living, which was very different from the latter narrative.

We were not born to be chair livers, eating factory fare and keeping sleep hours like a vampire (unless we’re in college, that is). Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, and Chapter 9 will fill in just about all you need to know about eating right, kicking up your heels, and getting some rest. We need to find another design pattern.

I tend to agree with the meme, or paradigm, that has made its way about the Web and even among the scientific journals (call it “paleo,” ancestral health, the return to Eden, or whatever you want to) that we were born to move around in sunlight, eat real food, and sleep much more than our friends want us to (you know, the ones who are knocking on the door right now and trying to get you to go to that party).

As a geek, think of our situation this way. We’re all born with preinstalled software, our human codebase. The genome. You know, the curlicues of DNA in our chromosomes inside the nuclei of most cells: all that ATGC code that defines what we are biologically. It is kind of cool, almost mesmerizing, how Mother Nature seems to have her own software language. Perhaps we’ve subconsciously invented computer programs that have the look and feel of our own internal code.

Note

See this page at 23andMe for a nice refresher or primer on genes and genetics: www.23andme.com/gen101/genes/.

It took hundreds of thousands of years to write this software. The evolutionary process is very slow, meaning we haven’t changed very much in thousands of years. We’re all separated by tiny changes in our genes, such as the fact that some people can’t digest lactose that well and others eat asparagus and sense a different smell in their pee (really).

Note

“The spontaneous mutation rate for nuclear DNA is estimated at 0.5% per million years. Therefore, over the past 10,000 years there has been time for very little change in our genes, perhaps 0.005%,” comments Artemis P. Simopoulos, M.D., of The Center for Genetics, Nutrition and Health, Washington, DC, USA, in a journal article from 2008.1

Our ancestors, with basically our genome, ate dead meat (as in, scavenged), wild meat that they hunted, stuff that grew, tree nuts, whatever lake or sea foods they could grab, and gobs of raw honey produced by swarms of bees made docile by the smoky fires lit beneath their nests.

Some of the time, as the weather was changing crazily around them (sound familiar?), they couldn’t find any food, for days—for weeks.

Whatever, essentially, our earliest forebears could eat to remain alive, they did eat. It all had to be hunted and wild; they didn’t have bodegas or convenience stores back then. They had to move to the food (no pizza deliveries or fancy caterers), and often had to chase and subdue it, if not fend off other predators who sought to reclaim their carcasses. They were outside a good chunk of the time during daylight hours.

We’re so close to these ancient forebears biochemically that molecular biologists have hypothesized a link from each of us to an ultimate Mom, a primordial Eve (see the sidebar, The Ultimate Super Mom: Mitochondrial or African Eve).

Imagine that you’re standing next to your grandmother in a long line. She is standing next to her mother, and then your grandmother’s grandmother is the next Mom in line after that, and the string of people extends for “10,000 grandmothers,” as the author Brian Fagan puts it in his book Cro-Magnon: How the Ice Age Gave Birth to the First Modern Humans. The 10,000th grandmother might be the ultimate Mom that all humans are related to.

The human genome goes back at least as far as about 2.5 million years, when the Lower Paleolithic era began (otherwise known as the early Stone Age). Actually you could trace our genes back quite a bit further, but for the sake of brevity we’ll start with an upright ancestor that used tools 2.5 million years in the past called homo habilis.

He was followed by homo erectus, who trekked around his wild habitat (and often booked out of there as fast as he could) around one million years ago, and homo sapiens about half a million years ago. The most advanced and successful ancestor who wandered out of our original African habitat and established herself in Europe was Cro-Magnon, who thrived in that region beginning about 50,000 years ago. We’re quite similar, anatomically and genetically, to these guys and gals.2

The typical way to express the idea of us carrying the preinstalled software of those prehistoric guys and gals is that if those millions of years of human evolution could be compressed into a 24-hour clock, the last 10,000 years since the Agricultural Revolution would take place beginning at about five minutes to midnight.

The last 200 years of the Industrial Revolution began to take place at about five seconds to midnight. And the Digital Age... well, you get the metaphor. It’s been an eye blink, and evolution is not fast enough to redesign us for endless couch surfing!

It’s safe to say that the hunter-gatherers and us moderns are pretty similar in our genetic programming.

“Shallow” genetic changes that can dig in their heels faster are taking place all the time, according to Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending’s book The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution. These are variations on our genome; see the sidebar Night of the Mampires: How Genes Can Affect the Way We Handle Food.

About 99 percent of our genetic history, however, has been spent interacting with our environment more like a Maasai tribeswoman, a Plains Indian, or a modern lady getting her butt kicked during an Outward Bound course, rather than the characters depicted in the TV show Men of a Certain Age.

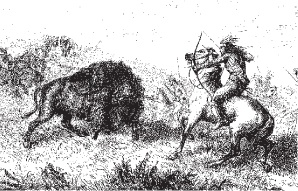

This has something to do with those eighteenth- to nineteenth-century Plains Indians being the buffest bad-asses in the world during their time.3 They were hunters who acted like hunter-gatherers and killed, ate, made stuff out of, and revered the American bison.

Here’s another evolution-related example, partly from Chapter 4 on micronutrients. We can’t biosynthesize or make our own vitamin C or vitamin E, as plants can (although we can biosynthesize vitamin D, from the sun). We therefore evolved to get vital micronutrients like vitamins from those photosynthesizing plants, as well as farther up the food chain, from the animals that munched the veggies. It’s part of our design; we eat plants and animals because, in turn, we need the C and E vitamins to keep our internal machinery going.

To reach the plants and animals, guess what, we had to be moving around in a cyclical pattern of hunt-gather-rest, then do-it-again. We are bipedal people, ambulatory by nature. Whether or not at any moment we could have been ripped asunder and devoured by wild beasts or stomped to death by the underestimated prehistoric bison (you can’t really sugarcoat that Paleolithic life, pun intended), this scenario still represents the diet and locomotive patterns that our ancestors, and we ourselves, were and have evolved for.

Is it possible to live in a way that completely undermines your own software configuration? Are we corrupting our own code? Well, yeah, I guess that’s where I’m leading, based on the aforementioned hypothesis of our closeness in design to our ancient forebears. Scientists call it evolutionary discordance.

The anthropologist Jared Diamond fumed in a famous essay from more than 20 years ago that the move to agriculture 10,000 years ago was “the worst mistake in the history of the human race” (Discovery Magazine, May 1987) and “a catastrophe from which we have never recovered.”

Diamond emphasized the rigid class-based systems and “gross social and sexual inequalities, the disease and despotism” that agricultural systems have bred, but there were other physical and health-related downsides as well, which persist in a different nature all the way up to modern times.

Note

Don’t get the wrong impression from my knocks against the Ag Revolution—I love farms, particularly of the small and local variety. I just returned from one, with a juicy bag of salad materials, Macintosh apples, and blueberries. The point of this passage is that the transition from hunter-gatherer to the diet of agriculturalists had bad health consequences that are relevant today (i.e., we’re still bedeviled by a high-quantity, low-nutrition diet).

See the sidebar A Tale of HOE: Protein and thus Height “Tanked” for what the effect of the agricultural transition was on height and health in general.

The oft-stated disclaimer is that all this hunter-gatherer talk is baloney: human longevity has never been greater than it is now, and even inside bustling, youth-oriented places like Manhattan, you can find many centenarians. In contrast, the lives of our Paleolithic ancestors were “nasty, brutish, and short,” maybe averaging a third or less the length of one of those centenarians’.

A big problem with that argument, as a number of essayists have pointed out, is the concept of using an “average lifespan” to describe the health of a population of people.

As Jeff Leach pointed out in an October 2010 letter titled “Paleo Longevity Redux” in Public Health Nutrition:

The first problem with this thinking is the “average life span” math is misleading and tells us very little about the health and longevity of an individual, but rather gives us an average age of death for a given group or population. For example, a couple that lived to the ages of 76 and 71, but had one child that died at birth and another at age two ([76+ 71 + 0 + 2] / 4), would produce an average life span of 37.25. Using this methodology it is easy to see how one would come to the conclusion that this group was not very healthy.

Along the same lines, the author of The Black Swan, Taleb Nassim, pointed out in an essay called “Why I Walk”:

The argument often heard about primitive people living on average less than 30 years ignores distribution around such average—life expectancy needs to be analyzed conditionally. Plenty died early, from injuries, many lived very long—and healthy—lives. This is exactly the very same elementary “fooled by randomness” mistake, relying on the notion of “average” in the presence of variance, that makes people underestimate the risks in the stock market.

Undoubtedly, some of those ancient lives were “nasty, brutish, and short,” and inherently violent, without antibiotics, modern medicine in general, and a local police department.

In a way, the claims about brief Paleolithic lives are a red herring: the few remaining modern hunter-gatherers tend to go through their lives with only rare occurrences of the contemporary “diseases of Western civilization.”

Jeff Leach concludes his essay:

The self-confidence that comforts us today as we review the average life span of our ancestors is misguided and tenuous when viewed through the captivating haze of modern medicine that literally props most of us up into our golden years. I doubt our ancestors would call this living. While we may live longer than our ancestors, we are in fact dying slower.

Note the “mismatch between genes and the environment” point in the “Tale of Hoe” sidebar. Things are at least as bad now in modern society as they were during the dawn of the agricultural age (at least those early farmers spent a lot of time outside doing hard-scrabble chores in sunlit gardens).

The World Health Organization estimates that lifestyle-oriented diseases will cost the global economy $30 trillion over the next 20 years (that includes smoking and alcohol abuse, as well as chowing down sugary and salt-laden snack foods).10

What’s going on here—why do we have such a massive health crisis? Don’t our experts have an incredibly deep and nuanced knowledge about how health and the body function? We’ve sequenced the human genome. We’re even working on “nutrigenomics,” or specifically tailoring nutrition and supplements to a person’s genes.

I guess health isn’t exclusively about science, medical practices, or conventional public-health recommendations, or we’d be able to apply that knowledge about how to stay healthy with greater success than we do. Couldn’t we do a better job of embracing a new design pattern, one based on our own inherited operating systems?

In a 2005 article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the medical doctor Boyd Eaton and his colleagues pointed out how lame the diet many of us depend on—which is commonly lampooned as the Standard American Diet (SAD)—is:11

Although dairy products, cereals, refined sugars, refined vegetable oils, and alcohol make up 72.1% of the total daily energy consumed by all people in the United States, these types of foods would have contributed little or none of the energy in the typical preagricultural hominin diet.

In a word, ouch!

Boyd Eaton also pointed out in a recent speech that “50 percent of our ancestor’s diet was fruits and vegetables; now for Americans it’s 13 percent, which represents a huge [decline]” in antioxidant intake (see the sidebar in Chapter 4 on those all-important antioxidants). “The skin of the fruit contains most of the antioxidants, and the smaller wilder fruits contain more antioxidants,” given that you have to eat more fruit skin with the smaller, wilder varieties to fill up on fruit servings.

Note

Taking this point to heart, I ate a lot of apples off an apple tree in Vermont this summer and early fall. The apples were smaller; I thus ate more skin and presumably antioxidants compared with larger, sweeter, store-bought apples. The apples were tarter off the tree, perhaps containing less fructose (you should watch the fructose load in your diet—see Chapter 3 on macronutrients). And hey, I had to jump and climb to get the apples, which had to be more active than cruisin’ the checkout aisles!

Eaton and his colleagues have hypothesized, along with other researchers, that the “diseases of civilization,” like cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and depression, could be caused by this evolutionary discordance in food intake.

In addition, some studies have pointed to the lack of physical exercise as more evidence that we are badly out of sync with our built-in codebase.

“Recent cultural changes have engineered physical activity out of the daily lives of humans,” pointed out Manu Chakravarthy and Frank W. Booth in the Journal of Applied Physiology in 2004:12

As a result of the introduction of habitual physical inactivity into the pattern of daily living, the risks of at least 35 chronic health conditions have increased...we will speculate that the feast-famine cycling and physical activity-rest cycling that were related to food procurement for [hunter-gatherers] selected genes for an oscillating enzymatic regulation of food-storage and usage.

Note

If physical activity is part of our design, why did we engineer it out of our lives? One answer is the pervasiveness of technology, which it turns out controls us, rather than the other way around. Screen life requires immobility in front of screens. In addition, we no longer have to “go get” vitamins to stay alive—they’re within an arm’s reach on the shelf or easily acquired without even leaving a sitting position in the car (although convenience foods often lack those very vitamins). Modern food is ubiquitous.

Ironically, our own built-in “man-page” (the software instructions for the Unix operating system) carries the imprint of our earliest low-tech ancestors, and provides many clues for maintaining fitness.

Of course, most of us cannot dash out the back door and give the hunter-gatherer life the old college try.

Nor can I advocate that we all sprint out into the woods with scary face masks and beat drums, throw spears at shadows, and howl at the moon (although, now that I mention it, what a blast that would be). We can initiate a kind of mashup of modern and ancient life, though. Our preloaded software represents a useful template with which we can assess our own daily choices. We know what we’re designed for; we read this book!

We’ve discussed nutrition a bit up to now; the rest of the book launches into the savory subjects of food, fitness, and exercise in quite a bit of detail. The movement angle of fitness is obviously very important, but to what degree?

Will Ferrell leans back in the movie Wedding Crashers and memorably cries out, “Hey Ma—the meatloaf—we want it now—the meatloaf!” He crystallizes an evolving biological tribe we could call Homo barcalounger.

We’ve become a species of sitters, as eloquently put by a doctor in a recent online issue of the Brooklyn Eagle:13

We move from the chair in the car to the chair in front of the computer in the office; then we go home in the chair in the car to the chair in front of a copious dinner to the chair in front of the TV. The next day the cycle repeats itself. We sit too much.

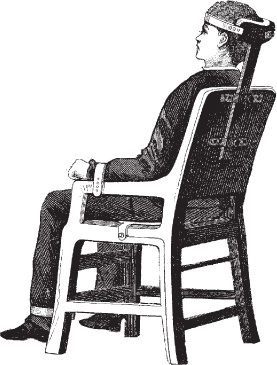

Believe it or not, scientists have coined a term for this trend: chair living. It has been a part of cubicle life for us geeks since the early epochs of the digital age, but many of us, along with others of the deskbound variety, have since altered our workstations to combine standing with computer work (check out the stand-up workstation called the GeekDesk at www.geekdesk.com).

Chair living apparently takes sedentary living to a new level.

If you’re like me, you probably think of sitting as an activity that is as common as, well, standing, and that might be bad for you if you did it for 25 years in a row. It’s much worse than that, apparently.

As James Levine, an M.D. at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, wrote in a November 10, 2010, journal article, “a growing body of evidence suggests that chair-living is lethal... linked to cardiovascular disease, metabolic [problems], excess weight, and shorter life span.”14

You can read that article and weep, then, consequently, leap out of your chair. Levine goes on:

The human evolved over several million years to be bipedal and ambulatory. This time frame is consistent with the genetic and epigenetic design of the human physique and organ systems. Neuro-behaviorists would argue that the human brain and behavior evolved in concert. The human evolved to competitively flourish while upright with respect to providing food (agriculture and hunting), shelter (home building), and tool design (e.g., flint knives). The human evolved to feed, shelter, and invent while ambulatory. The human, simply put, was not designed to sit all day.

A very useful measure of how much we are moving throughout the day is the metabolic equivalent of task (MET), or just metabolic equivalent. It’s a simple way to quantify our energy output, and it starkly underlines the differences between sitting and real movement. The MET is designed to represent the amount of energy in the form of heat we’re generating, using a numeric multiple. For example, reclining in a chair is 1 MET; sleeping is 0.8.15

This scale moves all the way up through walking about a mile per hour on the flat (1.9), actively raking leaves (2.9), light biking or golf (5.0), to running 12-minute miles (8.5), to running faster than nine miles an hour (9.5).

We’re going to be returning to METs throughout this book, particularly in the tools and exercise chapters. For example, Chapter 2 discusses a nifty little gadget called the Fitbit that you can use to measure your average MET for a day.

The bottom line is that you want to push up your MET for the day, because it’s what we’re designed for. We seem to be evolved for a steady oscillation of physical activity throughout the day, along with short bursts of intense, almost scary effort (yeah, exercise can be hormesis!—see Chapter 11).

By now it should be obvious that we are built to eat Mother Nature’s food, such as wild (or wild-like) meat or fish, and multicolored plants that come from organic farms and leap from the pages of Mother Earth magazine. We’re supposed to boogie down, and we’re not designed for self-imposed muscular paralysis. You might even think that this chapter belabors these points, which would amount to a harangue if not for the fact that most of these negative trends are instantly reversible.

I won’t include much in this chapter about the specifics of fitness-oriented exercise and training, because so much of the book (see Chapter 2, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8) is crammed with various techniques for sprinting, resistance training, trekking (with or without weighted vests), and more for capturing all of your exercise data on a web page for various forms of analysis.

This chapter will conclude on an upward swing with the flip side of the “daily grind” we began with. It includes a couple of adjustments that bring it much closer to our installed software base—and our own pursuit of optimal fitness.

Try this: you wake up without an alarm sometime soon after sunrise, with plenty of time to spare to make it to work.

It was a good sleep; you went to bed just after nine o’clock after having a snack consisting of coconut milk blended with blueberries and a little whey powder. You’re already savvy about getting enough REM sleep, but now you aim to bump up your deep sleep, or restorative NREM. You might even check out the wave chart your Zeo produced.

The first thing you do is pour a cup of black tea or coffee and go outside to this pool of sunlight you’ve noticed out your window.

You bask and reflect in it for a minute, perhaps followed by a few Tai Chi moves, push-ups on the lawn, or pull-ups on the jungle gym across the street from your apartment. You sip a bit more coffee and return to your living space to get ready for the commute.

Technically speaking, as you gazed up into the sky and basked in that sun, the light rays touched your retinas and were transduced by the hypothalamus and pineal gland in your brain, which has now helped set your circadian rhythms for the day.

The sun you got wasn’t much, not like spending the morning on the beach in the British Virgin Islands (gotta do that someday...), but it had the effect of lightening your mood, clearing your head, and kick-starting the day. You’ve sent the message to your body and your brain, “It’s morning and I’m well rested and ready to go.” (See Chapter 9 for more info on the health importance of sleep and rest.)

Every other day you stop at an intervening fitness facility to lift a few weights or do a 300-yard swim interspersed with a handful of 25-yard sprints—nothing too much, but today you’re biking to the train station, where they’ve thoughtfully included a place to lock your rig.

The train ride into the center of the city (Boston, New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Portland, Vancouver, Montreal; Zurich, Frankfurt, Copenhagen, London, Sydney, Wellington, Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto...) takes 35 minutes, and you stand for most of it, just because it feels better.

You kind of want to rack up more activity points on this web-connected, motion-sensitive, stair-counting altitude calculator you’ve clipped onto your belt (yeah, it’s called a Fitbit), although gear isn’t strictly necessary this morning. It’s just fun, in a geeky kind of obsessive way. You like quantifying and logging your exercise. This act itself seems motivating. The web charts your gear generates later are actually quite impressive. They can show your oscillating movement throughout the day, and pinpoint the days when you need more.

Gathering data is not useless when you act upon it.

The tool for adding up your daily motion mileage works with an odd “tail wagging the dog” effect; you seem to move more when you’re wearing it. Further, you never really knew that ordinary movement could equate to that much mileage during the day. More than six miles sometimes, even though your walks were broken up into several smallish ones.

Plodding along on a treadmill just isn’t necessary anymore. You love looking at the stats at the end of the day. Just keep moving, you say to yourself. Seek the sun.

Breakfast today was two hard-boiled eggs (eggs bought the previous weekend at a farmer’s market), a piece of Swiss cheese, a bite of salmon left over from last night, and two plums plus an avocado (also purchased at the market). Yesterday, you fasted through breakfast, and that felt fine. Actually, the bit of coffee plus “intermittent fast” kept you pretty perky throughout the morning. (See Chapter 6 for more on intermittent fasting.)

You’ve got a little plastic bag in your backpack containing the rest of the salmon, a mixture of almonds and walnuts, an apple, and a square of 85% high-cacao chocolate. In a pinch, there’s a good salad place near work. It only took a couple of weeks not to miss that bagel anymore, and especially all that crappy margarine (you go for really yellow butter now)—the sluggishness and lack of satiety it seemed to leave you with, and the way it seemed to take half the morning to digest it and the donut and scone you piled on top of it.

Hopping off the train, you walk about 30 minutes the rest of the way to work, on the sunny side of the street, even though you could have dipped into the subway or hopped on a bus.

Work is on the third floor of a tall building, but you take the stairs, walking briskly past a line of people waiting at the elevator. Their auras are uniformly glum, as if someone else is pulling their strings. You have never taken the elevator, including that time your supervisors were standing in front of it with expectant looks, suggesting they had an axe to grind.

You take the stairs two at a time, simply because the heft in your upper leg feels good. Your heart rate gets going, but not that much; you’ve noticed that improvement over the months.

The morning goes on and you switch between sitting and standing in your cubicle—standing most of the time. You have a pretty good stand-up workstation setup. Besides, the standing for hours bumps up those motion-and-mileage numbers, which no one else could possibly care about, except other users fidgeting with their tracking devices and apps and going online afterward with the data. You don’t mind having an obsessive-compulsive disorder involving healthy habits. You also don’t mind going without your gear for a day or two. No big deal.

About every hour or 90 minutes during the day, you head down those stairs again and back outside into the sun. When you get blocked on a sticky piece of code or logical problem, this brisk walk helps almost every time. Often, you experience casual moments outside that you always will remember and never would have experienced if you’d stayed in your cubicle all day, like that majestic hawk that hovered in the blue sky before it alighted on the ledge of a distant building.

You tried to estimate its wingspan as it hung frozen in the cerulean blue.

That handsome dude or attractive woman with the healthy glow who spoke to you out of the blue that time when you were both sitting on a bench, chilling—that hadn’t happened to you in a long while; it’s usually just awkward silences and departures, ships passing at night. You’re going to see him/her again sometime; you’re going to swap phone numbers.

You take longer walks sometimes in the city, until you find yourself drifting around with a relaxed aimlessness, kind of like Owen Wilson in the movie Midnight in Paris.

You have the usual “meetings” (the quotation marks question their purposefulness) in the mid-morning and afternoon. You stand during both, and it seems to have a contagious effect. Two other people stood up during the second meeting, and you could have sworn both confabs went a little faster. You’re beginning to get a rep as “that healthy guy” around the office.

By the end of the day you’ve climbed about 12 floors and maybe walked a couple of miles or more (the number of miles you cover in a day, counting everything, always surprises you). A formal workout in the middle of the day is not necessary. But sometimes you duck into the company fitness facility on a rainy day and knock off some bench presses, pull-ups, and inverted push-ups. Sometimes it’s just a dash on a treadmill, or some karate kicks followed by Tai Chi. It takes no more than about 30 minutes.

Your workouts almost never exceed that length of time. When they do, horsing around would be a better way to describe them than workouts or training sessions: playing catch using a winged Nerf football with your son or a friend, or gliding along a country road on a mountain bike.

Are you getting the point here? You’re able to shoulder a pretty hard job and commute, while staying healthy, mindful, and reasonably content. The days seem to flow more, instead of banging together like an extended train wreck, with you occupying the middle passenger car. Who could argue with that? You even get the monthly $50 bonus they pay at work to the employees with the fewest sick days!

The intent of the last assemblage of paragraphs wasn’t to get all vainglorious and virtuous about healthy lifestyles—although it was fun to write—as much as to paint a narrative about surviving the Digital Age and emerging from your days mostly unscathed (maybe an occasional bruised ego, but it comes with the territory, right?). This chapter has introduced some basic fitness concepts that the rest of the book will cover in sometimes extensive detail:

Living in the Digital Age, where culture, data, and networks never sleep, but still incorporating the sun, lots of walking, and outdoor experiences—living closer to the imperatives of our preloaded software (our very deep past).

The benefits of whole, nonprocessed, real food—and even a bit of “intermittent” fasting every week.

The advantages of incorporating ordinary exercise regimes like stair climbing, lengthy, aimless walking (no matter how cold it is!), sprints, jumps, and hill-climbing extemporaneously, when you can.

Using useful tracking tools and personal metrics to augment your fitness, share your progress with friends, help others work through some physical glitches or sleep issues, or for just plain time-wasting fun (when you have that time, that is).

The importance of sleep and destressing; they could save your life.

The advantages of other lifestyle tactics like freezing swims, saunas, and fasting, not to mention moderate exercise and a good drink now and then. These are examples of “hormesis,” or good stress (see Chapter 11).

Unlike many faddish weight-loss and fitness schemes, the changes just described do not involve any expensive program or club fees, or drastic dietary changes (like “zero carb or fat”), except for the optional purchase of a few fun and useful gadgets or tools when you have a little extra change. In the next chapter, we look at some of these tools and apps with which you can analyze and quantify your fitness progress.

Get Fitness for Geeks now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.