As mentioned in this book’s introduction, Flash performs several feats of audio-visual magic. You use it to create animations, to display video on a website, to create handheld apps, or to build a complete web-based application. So it’s not surprising that the Flash workspace is crammed full of tools, panels, and windows (Figure 1-1). But don’t be intimidated—you don’t have to conquer these tools all at once. This chapter introduces you to Flash’s main work areas and often-used toolbars and panels, so you can start creating Flash projects right away. You’ll experiment with Flash’s stage and timeline, and see how Flash lets you animate graphics so that they move along a path and change shape.

Tip

To get further acquainted with Flash, you can check out the built-in help screens by selecting Help→Flash Help. Once the help panel opens, click Using Flash Professional. It’s on the left side of the somewhat busy window. You can read more about Flash’s help system in Appendix A.

You start Flash just as you would any other program—which means you can do it in a few different ways, depending on whether you have a PC or a Mac. Installing the program puts Flash CS6 and its related files in the folder with your other programs, and you can start it by double-clicking its icon. Here’s where it’s usually installed:

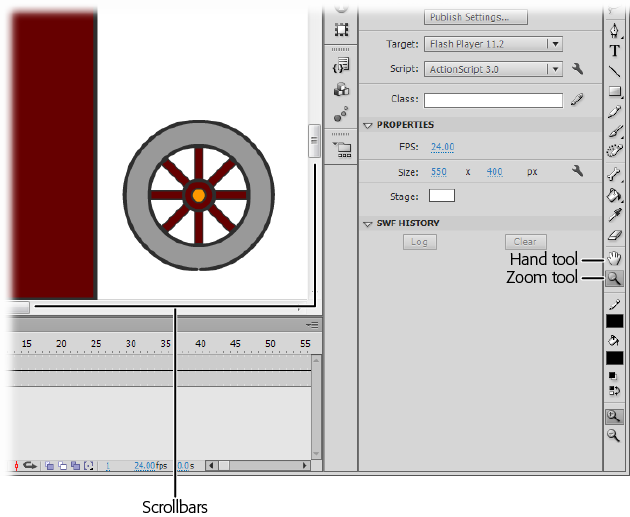

Figure 1-1. The Flash Professional workspace is divided into three main areas: the stage, the timeline, and the Panels dock. This entire window, together with the timeline, toolbars, and panels, is sometimes called the Flash desktop, the Flash interface, or the Flash authoring environment.

Here are some other Windows ways to start the program:

From the Vista or Windows 7 Start menu, choose All Programs→Adobe Flash Professional CS6.

For Windows XP, go to Start→All Programs→Adobe→Adobe Flash Professional CS6.

If you’re a keyboard enthusiast, press the Windows key and begin to type flash. As you type, Windows searches for a match and displays a list with programs at the top. Most likely, the Flash program is at the top of the list and already selected, so just press Enter. Otherwise, use your mouse or arrow keys to select and start the program.

Here are some Mac launching options:

Even if you haven’t added the Flash icon to the Dock, you can still find it in the Dock’s Applications folder. Click and hold the Applications folder icon and choose Adobe Flash CS6→Adobe Flash CS6.

Want to hunt down Flash in the Finder? Most of the time, it’s installed in Macintosh HD→Applications→Adobe Flash CS6→Adobe Flash CS6.

If you’d rather type than hunt, use Spotlight. Press ⌘-space and then begin to type flash. As you type, Spotlight displays a list of programs and files that match. Most likely, the Flash program is at the top of the list and already selected, so just press Return. Otherwise, use the mouse or arrow keys to select and start the program.

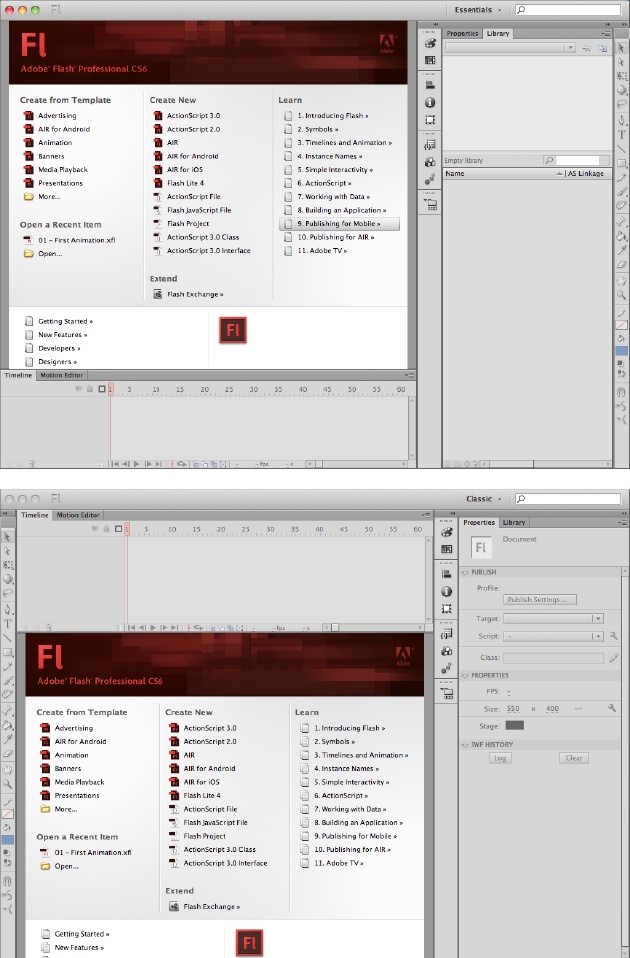

When you first start Flash, up pops the Welcome screen, shown in Figure 1-2. This screen puts all your options—like starting a new document or returning to a work in progress—in one handy place. For good measure, Adobe includes some links to help references and resources on its website.

Figure 1-2. This Welcome screen appears the first time you launch Flash—and every subsequent time, too, unless you turn on the “Don’t show again” checkbox (pull down the bottom of the window if you don’t see it). If you ever miss the convenience of seeing all your recent Flash documents, built-in templates, and other options in one place, then you can turn it back on by choosing Edit→Preferences (Windows) or Flash→Preferences (Mac). On the General panel, choose Welcome Screen from the On Launch pop-up menu.

Note

If Flash seems to take forever to open—or if the Flash desktop ignores your mouse clicks or responds sluggishly—you may not have enough memory installed on your computer. See Flash CS6 Minimum System Requirements for more advice.

When you choose one of the options, the Welcome screen disappears and your document takes its place. Here are your choices:

Create from Template. Clicking one of the little icons under this option lets you create a Flash document using a predesigned form called a template. A template helps you create an animation more quickly, since a Flash developer has already done part of the work for you. You can find out more about templates in Chapter 7.

Open a Recent Item. As you create new documents, Flash adds them to this list. Clicking one of the filenames listed here tells Flash to open that file. Clicking the folder icon lets you browse for and open any other Flash file on your computer.

Tip

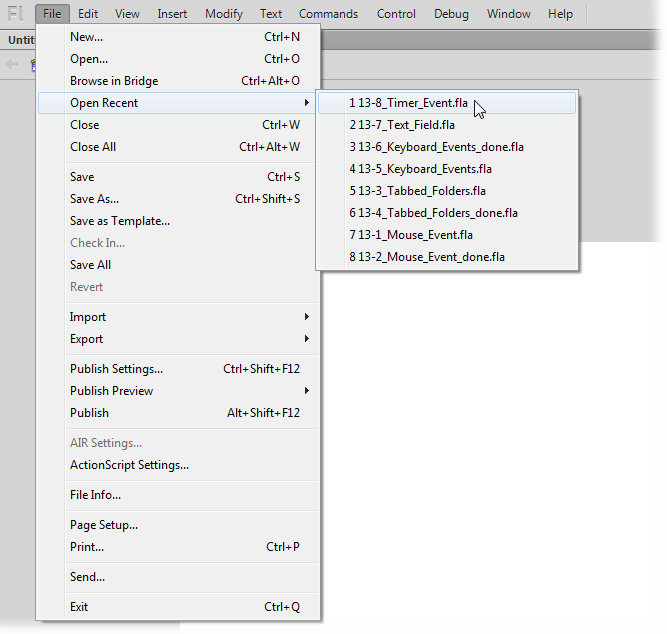

The options for creating new Flash documents and opening recent documents also appear on the File menu, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3. Several of the options on each menu include keystroke shortcuts that let you perform an action without having to mouse all the way up to the menu. For example, instead of selecting File→Save As, you can press Ctrl+Shift+S to tell Flash to save your Flash document. On the Mac, the keystroke is Shift-⌘-S.

Create New. Clicking one of the options listed here lets you create a brand-new Flash file. Most of the time, you want to choose the first option, ActionScript 3.0, which is a garden-variety animation file. ActionScript is the underlying programming language for Flash animations. The current version of ActionScript is 3.0, and it’s the version used for the projects in this book. You can use the ActionScript 2.0 option if you need to work with a Flash project that was created several years ago. For details on the file formats for different Flash projects, see the box below.

Extend. Clicking the Flash Exchange link under this option tells Flash to open your web browser and load the Flash Exchange website. There, you can download Flash components, sound files, and other goodies that you can add to your Flash animations. Some are free, some are fee-based, and all of them are created by Flashionados just like you.

Learn. As you might guess, these links lead to materials Adobe designed to help you get up and running. Click an option, and your web browser opens to a page on the Adobe website. The first few topics introduce basic Flash concepts like symbols, instances, and timelines. Farther down the list, you find specific topics for building applications for mobile devices or websites (AIR). At the bottom of the Welcome screen, “Getting Started” covers the very, very basics. “New Features” explains (and celebrates) some of Flash CS6’s new bells and whistles. “Developers” leads to an online magazine with articles and videos with an ActionScript programming slant. “Designers” leads to a similar resource for the Flash graphics and design community.

The best way to master the Flash CS6 Professional workspace is to divide and conquer. First, focus on the three main work areas: the stage, the timeline, and the Panels dock. Then you can gradually learn how to use all the tools in those areas.

One big source of confusion for Flash newbies is that the workspace is so easy to customize. You can open bunches of panels, windows, and toolbars. You can move the timeline above the stage, or you can have it floating in a window all its own. Once you’re a seasoned Flash veteran, you’ll have strong opinions about how you want to set up your workspace so the tools you use most are at hand. If you’re just learning Flash with the help of this book, though, it’s probably best if you set up your workspace so that it matches the pictures in these pages.

Fortunately, there’s an easy way to do that. Adobe, in its wisdom, created the Workspace Switcher—a tool that lets you rearrange the entire workspace with the click of a menu. The thinking is that an ideal workspace for a cartoon animator is different from the ideal workspace for, say, a rich internet application (RIA) developer. The Workspace Switcher is a menu in the upper-right corner of the Flash window, next to the search box. The menu displays the name of the currently selected workspace; when you first start Flash, it probably says Essentials. That’s a great workspace that displays some of the most frequently used tools. In fact, it’s the workspace used throughout most of this book.

Here’s a quick little exercise that shows you how to switch among the different workspaces and how to reset a workspace after you’ve mangled it by dragging panels out of place and opening new windows.

Start Flash.

Flash opens, displaying the Welcome screen. Unless you’ve made changes, the Essentials workspace is used. See Figure 1-4, top.

From the Workspace menu near the upper-right corner of the Flash window, choose Classic.

The Classic arrangement harkens back to earlier versions of Flash, when the timeline resided above the stage (Figure 1-4, bottom). If you wish, go ahead and check out some of the other layouts.

Choose the Essentials workspace again.

Back where you began, the Essentials workspace shows the timeline at the bottom. The stage takes up most of the main window. On the right, the Panels dock holds toolbars and panels. Now’s the time to cause a little havoc.

In the Panels dock, click the Properties tab and drag it to a new location on the screen.

Panels can float, or they can dock to one of the edges of the window. For this experiment, it doesn’t matter what you choose to do.

Drag the Color and Swatches toolbars to new locations.

The Color toolbar has an icon that looks like an artist’s palette at the top. Like the larger panels, toolbars can either dock or float. You can drag them anywhere on your monitor, and you can expand and collapse them by clicking the double-triangle button in their top-right corners.

Go to Window→Other Panels→History.

Flash has dozens of windows. Only a few are available now, because you haven’t even created a document yet.

Tip

As you work on a project, the History panel keeps track of all your commands, operations, and changes. It’s a great tool for undoing mistakes. For more details, see Other Flash Panels.

From the Workspace menu, choose Reset Essentials.

The workspace changes back to the original Essentials layout, even though you did your best to mess it up.

Anytime you want your workspace to match the one used throughout most of this book, do the “Essentials two-step”: Choose Essentials from the Workspace Switcher (if you’re not already there), and then choose Reset Essentials. As shown in Figure 1-4, when you use the Essentials workspace, the Flash window is divvied up into three main work areas: the stage (upper left), the timeline (lower left), and the panels dock (right). Before exploring each of these areas in detail, here are a few words about Flash’s menu bar.

Like most computer programs, Flash gives you menus to interact with your documents. In traditional fashion, Windows menus appear at the top of the program window, while Mac menus are always at the very top of the screen. The commands on these menus list every way you can interact with your Flash file, from creating a new file—as shown on Starting Flash—to editing it, saving it, and controlling how it appears on your screen.

Some of the menu names—File, Edit, View, Window, and Help—are familiar to anyone who’s used a PC or a Mac. Using these menu choices, you can perform basic tasks like opening, saving, and printing your Flash files; cutting and pasting artwork or text; viewing your project in different ways; choosing which toolbars to view; getting help; and more.

To view a menu, simply click the menu’s name to open it, and then click a menu option. If you prefer, you can also drag down to the option you want. Let go of the mouse button to activate the option. Figure 1-3 shows you what the File menu looks like. Most of the time, you see the same menus at the top of the screen, but occasionally they change. For example, when you use the Debugger to troubleshoot ActionScript programs, Flash hides some of the menus not related to debugging.

Tip

You’ll learn about specific commands and menu options in their related chapters. For a quick reference to all the menu options, see Appendix B.

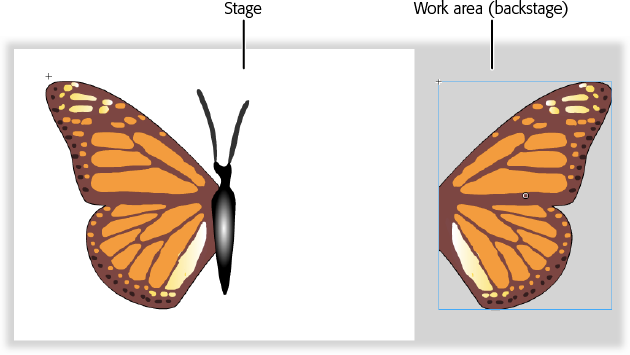

As the name implies, the stage is usually the center of attention. It’s your virtual canvas. Here’s where you draw the pictures, display text, and make objects move across the screen. The stage is also your playback arena; when you run a completed animation—to see if it needs tweaking—the animation appears on the stage. Figure 1-5 shows a project with an animation under construction.

Figure 1-5. The stage is where you draw the pictures that will eventually become your animation. The work area (light gray) gives you a handy place to put graphic elements while you figure out how you want to arrange them on the stage. Here a text box is being dragged from the work area back to center stage.

The work area is the technical name for the gray area surrounding the stage, although many Flashionados call it the backstage. This work area serves as a prep zone where you can place graphic elements before you move them to the stage, and as a temporary holding pen for elements you want to move off the stage briefly as you reposition things. For example, let’s say you draw three circles and one box containing text on your stage. If you decide you need to rearrange these elements, you can temporarily drag one of the circles off the stage.

Note

The stage always starts out with a white background, which becomes the background color for your animation. Changing it to any color imaginable is easy, as you’ll learn in the next chapter.

You’ll almost always change the starting size and shape of the stage depending on where people will see your finished animation—in other words, your target platform. If your target platform is a smartphone, for example, you’re going to want a smaller stage. If, on the other hand, you’re creating an animation for a ballpark’s JumboTron, you’re going to want a giant stage. You’ll get to try your hand at modifying the size and background color of the stage later in this chapter.

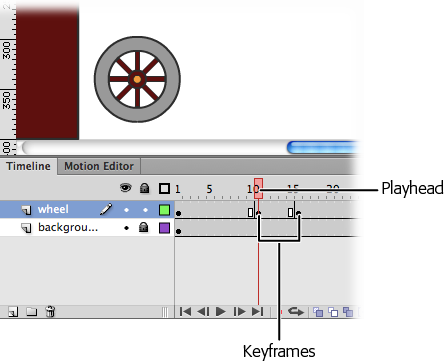

When you go to the theater, the stage changes over time—actors come and go, songs are sung, scenery changes, and the lights shine and fade. In Flash, you’re the director, and you get to control what appears on the stage at any given moment. The timeline is the tool used to specify what’s seen or heard at a particular moment. The concept is pretty simple, and if you’ve ever used video editing software, it will be familiar. Flash animations (or movies) are organized into chunks of time called frames. Each little box in the timeline represents a frame or a point in time. You use the playhead, shown in Figure 1-6, to select a specific frame. So when the playhead is positioned at Frame 10, the stage shows what the audience sees at that point in time.

Figure 1-6. The playhead is a red box that appears in the timeline; here the playhead is set to Frame 10. You can drag the playhead to any point in the timeline to select a single frame. The Flash stage shows exactly what’s in your animation at that point in time.

The timeline is laid out from left to right, starting with Frame 1. Simply put, you build Flash animations by choosing a frame with the playhead and then arranging the objects on the stage the way you want them. The timeline uses a special tool called a keyframe (see Figure 1-6) to remember exactly what’s on stage at that moment. You’ll learn more about the keyframes and other timeline tools in Chapter 3. Most simple animations play from Frame 1 through to the end of the movie, but Flash gives you ways to start and stop the animation and control how fast it runs—that is, how many frames per second (fps) are displayed. Using some ActionScript magic, you can control the order in which the frames are displayed. You’ll learn how to do that on Organizing Your Animation.

Tip

The first time you run Flash, the timeline appears automatically, but occasionally you want to hide the timeline—perhaps to reduce screen clutter while you concentrate on your artwork. You can show and hide the timeline by selecting Window→Timeline or pressing Ctrl+Alt+T (or for the Mac, Option-⌘-T).

If you followed the little exercise on A Tour of the Flash Workspace, you know you can put panels and toolbars almost anywhere onscreen. However, if you use the Essentials workspace, you start off with a few frequently used panels and toolbars docked neatly on the right side of the program window.

It’s easy to get confused by the Flash nomenclature. Flash has toolbars, panels, palettes, and windows. Sometimes collapsed panels look like toolbars and open up when clicked—like the frequently used Tools panel. Toolbars and panels pack the most commonly used options together in a nice compact space, so you don’t have to do a hunt-and-peck through the main menu every time you want to do something. Panels are great, but they take up precious real estate. As you work, you can hide certain tools to get a better view of your artwork. (You can always get them back by choosing their names from the Window menu.)

Toolbars and panels are such an integral part of working with Flash that it’s helpful to learn some of their tricks early on:

Move a panel. Just click and drag the tab or top of the panel to a new location. Panels can float anywhere on your monitor, or dock on an edge of the Flash program window (as in the Essentials workspace). For more details on docking and floating, see the box on Docked vs. Floating.

Expand or collapse a panel. Click the double-triangle button at the top of a panel to expand or collapse it. Collapsed panels look like toolbars, showing a few icons that hint at the tools’ purposes. Expanded panels take up more real estate, but they also give you more details and often have word labels for the tools and settings.

Show or hide a panel. Use the Window menu to show and hide individual panels. Checkmarks appear next to the panels that are shown.

Close a floating panel. In Windows, click the small X in the panel’s upper-right corner. On the Mac, click the X in the upper-left corner.

Show or hide all panels. The F4 key works like a toggle, hiding or showing all the panels and toolbars. Use it when you want to quickly reduce screen clutter and focus on your artwork.

Separate or combine tabbed panels. Click and drag the name on a tab to separate it from a group of tabbed panels. To add a tab to a group, just drag it into place.

Reset the panel workspace. Choose Reset <workspace name> from the Workspace Switcher. Instead of <workspace name>, you see the name of the current workspace—something like Essentials or Classic. You can also do a reset using the menus; choose Window→Workspace→Reset <workspace name>.

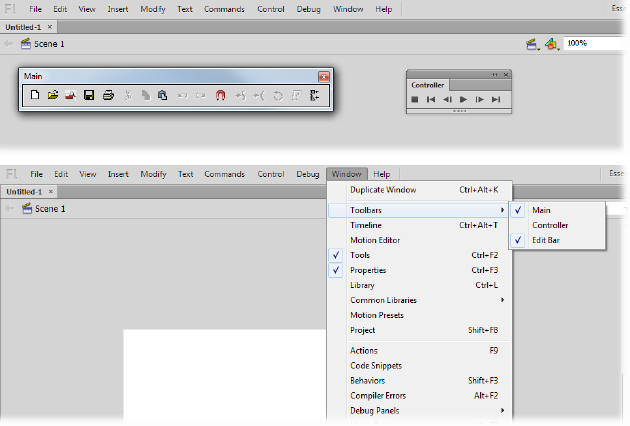

Figure 1-7. Top: To conserve space on Flash’s jam-packed desktop, only one toolbar—the Edit bar—appears automatically. It’s positioned directly above the stage. To display the other two, select Window→Toolbars→Main (to display the Main toolbar, Windows only) and Window→Toolbars→Controller (to display the Controller window). Bottom: The checkmarks on the menu show when a toolbar is turned on. Choose the toolbar’s name again to remove the checkmark and hide the toolbar.

Note

When you reposition a floating toolbar, Flash remembers where you put it. If, later on, you hide the toolbar—or exit Flash and run it again—your toolbars appear exactly as you left them. If this isn’t what you want, use the Workspace Switcher to choose a new workspace layout or to reset the current workspace.

Strictly speaking, Flash has only three toolbars: Main, Controller, and Edit. (Everything else is a panel, even if it looks suspiciously like a toolbar.) Figure 1-7 shows all three toolbars.

Main (Windows only). The Main toolbar gives you one-click basic operations, like opening an existing Flash file, creating a new file, and cutting and pasting sections of your drawing.

Controller. If you’ve ever used a DVD player or an iPod, you’ll recognize the Stop, Rewind, and Play buttons on the Controller toolbar, which lets you control how you want Flash to run your finished animation. (Not surprisingly, the Controller options appear grayed out—meaning you can’t select them—if you haven’t yet constructed an animation.) With Flash Professional CS6, the Controller is a little obsolete, because now the same buttons appear below the timeline.

Edit bar. Using the options here, you can change your view of the stage, zooming in and out, as well as edit scenes (named groups of frames) and symbols (reusable drawings).

The Tools panel is unique. For designers, it’s probably the most used of all the panels and toolbars. In the Essentials workspace, the Tools panel appears along the right side of the Flash program window. There are no text labels, just a series of icons. However, if you need a hint, just hold your mouse over one of the tools, and a tooltip shows the name of the tool. So, for example, mouse over the arrow at the top of the Tools panel, and the tooltip says “Selection tool (V).” The letter in parentheses is the shortcut key for that tool. Press the letter V while you’re working in Flash, and your cursor changes to the Selection tool.

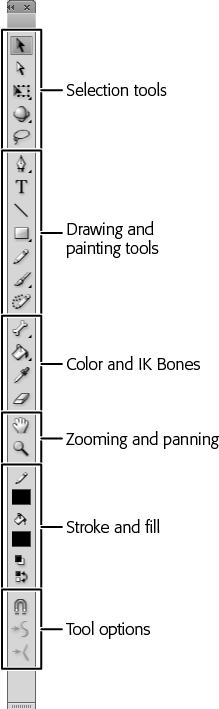

Most animations start with a single drawing. And to draw something in Flash, you need drawing tools: pens, pencils, brushes, colors, erasers, and so on. The Tools panel shown in Figure 1-8 is where you find Flash’s drawing tools. Chapter 2 shows you how to use these tools to create a simple drawing; this section gives you a quick overview of the six sections of the Tools panel, each of which focuses on a slightly different kind of drawing tool or optional feature.

At the top of the Tools panel are the tools you need to create and modify a Flash drawing. For example, you might use the Pen tool to start a sketch, the Paint Bucket or Ink Bottle to apply color, and the Eraser to clean up mistakes.

Figure 1-8. The Tools panel groups tools by different drawing chores. Selection and Transform tools are at the top, followed by Drawing tools. Next are the IK Bones tool and the Color tools. The View tools are for zooming and panning. The Color tools include two swatches, one for strokes and one for fills. At the bottom you find the Options buttons, which change depending on the drawing tool you’ve selected. If you like, you can drag the docked Tools panel away from the edge of the workspace and turn it into a floating panel.

At times, you’ll find yourself drawing a picture so enormous you can’t see it all on the stage at one time. Or perhaps you’ll find yourself drawing something you want to take a super-close look at so you can modify it pixel by pixel. In either of these situations, you can use the tools Flash displays in the View section of the Tools panel to zoom in, zoom out, and pan around the stage. (You’ll get to try your hand at using these tools later in this chapter; see The Flash CS6 Test Drive.)

When you’re creating in Flash, you’re drawing one of two things: a stroke, which is a plain line or outline, or a fill, which is the area within an outline. You can use these tools to choose a color from the Color palette before you click one of the drawing icons to begin drawing (or afterward to change the colors, as discussed in Chapter 2). Flash applies that color to the stage as you draw.

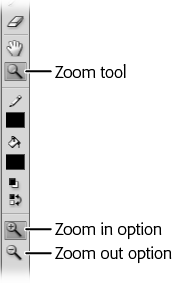

Which icons appear in the Options section at any given time depends on which tool you’ve selected. For example, when you select the Zoom tool from the View section of the Tools panel, the Options section displays an Enlarge icon and a Reduce icon that you can use to change the way the Zoom tool works (Figure 1-9).

Figure 1-9. On the Tools panel, when you click each tool, the Options section shows you buttons that let you modify that particular tool. In the Tools panel’s View section, for example, when you click the Zoom tool, the Options section changes to show you only zooming options: Enlarge (with the + sign) and Reduce (with the – sign).

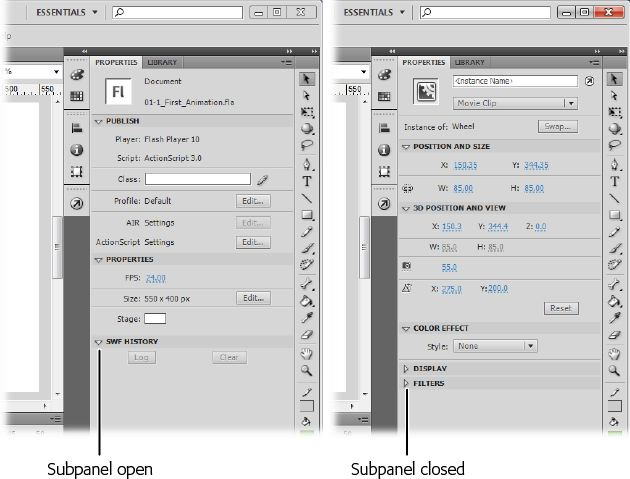

In many ways, the Properties panel is Command Central as you work with your animation, because it gathers all the pertinent details for the objects you work with and displays them in one place. Select an object, and the Properties panel displays all of its properties and settings. It’s not just an information provider; you also use the Properties panel to change settings and tweak the elements in your animation. When there’s fine-tuning to be done, select an object and adjust the settings in the Properties panel. (You can learn more in the “Test Drive” section on The Flash CS6 Test Drive.)

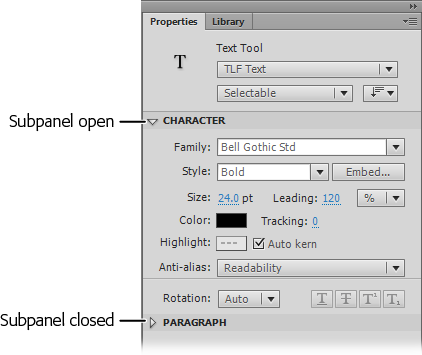

The Properties panel usually appears when you open a new document. Initially, it shows information about your Flash document, like the stage dimensions and the animation’s frame rate. Whenever you select an individual object in your animation, the Properties panel shows that object’s details. For example, if you select a text field, the Properties panel lists the typeface, font size, and text color. You also see information on the paragraph settings, like the margins and line spacing. Because the Properties panel crams so many details into one place, you’ll find yourself using the collapse and expand buttons to show and hide some of the information in its subpanels, as shown in Figure 1-10.

Figure 1-10. The Properties panel shows only those properties associated with the object you’ve selected on the stage. Here, because a text field is selected, the Properties panel gives you options you can use to change the typeface, font size, font color, and paragraph settings. Click the triangular expand and collapse buttons to show and hide details in the Properties panel.

Note

If you don’t see the Properties panel, you can display it by selecting Window→Properties or by pressing Ctrl+F3 (⌘-F3 on a Mac).

On the Properties panel, you see different subpanels depending on the object you’ve selected. Some objects have a lot of settings, and subpanels are Flash’s way of giving you access to all of them. Fortunately, the various panels and tools work consistently. For example, many objects have settings that determine their onscreen positions and define their width and height dimensions. These common settings usually appear at the top of the Properties panel, and you set them the same way for most kinds of objects. If you want to change colors or add special effects like filters or blends, you’ll find that the tools work the same way throughout Flash.

The Library panel (Figure 1-11) is a place to store objects you want to use more than once. Let’s say, for example, that you create a picture-perfect bubble, sun, or snowflake in one frame of your animation. (You’ll learn more about frames on Frame-by-Frame Animation.) Now, if you want that bubble, sun, or snowflake to appear in 15 additional frames, you could draw it again and again, but it really makes more sense to store a copy in the current project library and then just drag it to where it’s needed on those other 15 frames. This trick saves time and ensures consistency to boot. The Library panel has quite a few other important tricks, and you’ll learn more about it on Symbols and Instances. To show the Library panel, click Window→Library, or press Ctrl+L (Windows) or ⌘-L (Mac).

Tip

In the upper-right corner of most panels is an Options menu button. When you click this button, a menu of options appears—different options for each panel. For example, the Color Swatch panel lets you add and delete color swatches. You’ll find many indispensable tools and commands on the Options menus, so it’s worth checking them out. You’ll learn about different options throughout this book.

Figure 1-11. Storing simple images as reusable symbols in the Library panel does more than just save you time: It saves you file size, too. (You’ll learn a lot more about symbols and file size in Chapter 7.) Using the Library panel you see here, you can preview symbols, add them to the stage, and easily add symbols you created in one Flash document to another.

As you can see from the examples on the preceding pages, each Flash panel performs specific functions, and most of them deserve several pages to describe them fully, as you’ll find throughout this book. For now, Table 1-1 gives a thumbnail description and notes the page where the panel is described in detail. If you’re eager to get started actually using Flash, jump to The Flash CS6 Test Drive to start the Flash CS6 Test Drive.

Table 1-1. Flash Panels and their uses (in order as they appear on the Window menu)

PANEL NAME | KEYBOARD SHORTCUT | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|

Timeline | Windows: Ctrl+Alt+K Mac: Option-⌘-T | Technically, the timeline is just another panel. You can move, hide, expand, and collapse the timeline just as you would any other panel. See Frame-by-Frame Animation for more. |

Motion Editor | none | A powerful tool used to create and control animation effects. See A Tour of the Motion Editor for more. |

Tools | Windows: Ctrl+F2 Mac: ⌘-F2 | Perhaps the most frequently used panel of all—it holds drawing, selecting, and coloring tools. The Tools panel also includes specialized tools like the IK Bones tools and the 3D Rotation tool. See Using Merge Mode and Object Mode Together for more. |

Properties | Windows: Ctrl+F3 Mac: ⌘-F3 | Everything that appears on the stage has properties that define its appearance or characteristics. Even the stage has properties, like width, height, and background color. You can review and edit an object’s properties in the Properties panel. See Color Tools for more. |

Library | Windows: Ctrl+L Mac: ⌘-L | Holds graphics, symbols, and entire movies that you want to reuse. See Symbols and Instances for more. |

Common Libraries | none | When you want to share buttons, classes, or sounds among several different Flash documents, use the common libraries. That way, they’ll be available to all your projects. See the tip on Tip for more. |

Motion Presets | none | Serves up dozens of predesigned animations. See Applying Motion Presets for more. |

Actions | Windows: F9 Mac: Option-F9 | You use this panel to write ActionScript code. The Actions panel provides a window for code, a reference tool for the programming language, and a visual display for the object-oriented nature of the code. See Writing ActionScript Code in the Timeline for more. |

Code Snippets | none | Contains predesigned chunks of code—someone else sweated the details so you don’t have to. Specific bits of code perform timeline tricks, load or unload graphics, handle audiovisual tasks, and program buttons. See the box on Create an Event Handler in a Snap for more. |

Behaviors | Windows: Shift+F3 Mac: Shift-F3 | The earlier version of ActionScript (version 2.0) uses this panel to provide predesigned bits of code. |

Compiler Errors | Windows: Alt-F2 Mac: Option-F2 | Here’s where you troubleshoot ActionScript code. Messages explain the location of an error and provide hints as to what went wrong. See Setting and Working with Breakpoints for more. |

Debug Panels | none | Additional panels to help you find errors in your ActionScript programs. See Analyzing Code with the Debugger for more. |

Movie Explorer | Windows: Alt+F3 Mac: Option-F3 | Helps you examine the elements in your Flash animation, including separate scenes if you’ve created them. The display uses a tree structure to show the relationship of the elements. |

Output | Windows: F2 Mac: F2 | Another place to debug ActionScript programs. The Output panel is used to display text messages at certain points as a program runs. See Using the Output Panel and trace() Statement for more. |

Align | Windows: Ctrl+K Mac: ⌘-K | Lets you align and arrange graphic elements on the stage. See Aligning Objects with the Align Tools for more. |

Color | Windows: Shift+F9 Mac: Shift-⌘-F9 | Lets you select and apply colors to graphic elements. See Advanced Color and Fills for more. |

Info | Windows: Ctrl+I Mac: ⌘-I | Provides details about objects, like their location and dimensions. The Info panel also keeps track of the cursor location and the color immediately under the cursor. See Making It Move with Motion Tweens for more. |

Swatches | Windows: Ctrl+F9 Mac: ⌘-F9 | Colors and gradients that you can apply to graphic elements. You can create your own swatches for colors you want to reuse. See Specifying Colors for ActionScript for more. |

Transform | Windows: Ctrl+T Mac: ⌘-T | Lets you change the size, shape, and position of graphic elements on the stage. You can even use the Transform panel to reposition or rotate objects in 3-D space. See Transforming Objects for more. |

Components | Windows: Ctrl+F7 Mac: ⌘-F7 | Holds predesigned components you can use in your Flash projects. You’ll find user interface components like buttons and checkboxes, components that can be used to create data tables, and components used to control movie and sound players. See Reversing Frames in the Timeline for more. |

Component Inspector | Windows: Shift+F7 Mac: Shift-F7 | Provides compatibility with older animations. (Flash CS6 displays component properties in the Properties panel. Earlier versions of Flash used the Component Inspector. See the box on Learning the Parameters for more.) |

Accessibility (under Other Panels) | Windows: Alt+Shift+F11 Mac: Shift-⌘-F11 | Tools that help you ensure that vision- and hearing-impaired folks can enjoy the animations you create using Flash. See the box on Why Accessibility Matters. |

History (under Other Panels) | Windows: Ctrl+F10 Mac: ⌘-F10 | Lets you backtrack or undo specific steps in your work. Flash keeps track of every little thing you do to a file, starting with the time you created it (or the last time you opened it). You can also use this panel to save a series of commands you want to reuse later. |

Scene (under Other Panels) | Windows: Shift+F2 Mac: Shift-F2 | Helps you organize and manage your scenes. (You can break long Flash animations into separate scenes, as described on Working with Scenes.) |

Strings (under Other Panels) | Windows: Ctrl+F11 Mac: ⌘-F11 | Need to create an animation or application that works in different languages? Using the Strings panel, you can create and manage multi-language versions of the text. (This book doesn’t cover multi-language Flash.) |

Web Services (under Other Panels) | Windows: Ctrl+Shift+F10 Mac: Shift-⌘-F10 | Used only with ActionScript 2.0 projects that connect to the Internet. (This book doesn’t cover ActionScript 2.0.) |

For the tutorials in this section, you need a Flash animation to practice on. There’s one ready and waiting for you on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds/flashcs6mm. The file is named 01-1_First_Animation.fla.

Note

In case you’re wondering, the number 01 at the beginning stands for Chapter 1, and the -1 indicates it’s the first exercise in the chapter. Other Missing CD files for this book are named the same way. You can download all the exercise files in a single ZIP file or you can grab them chapter by chapter. The Missing CD also includes links to all the web-based resources mentioned in this book.

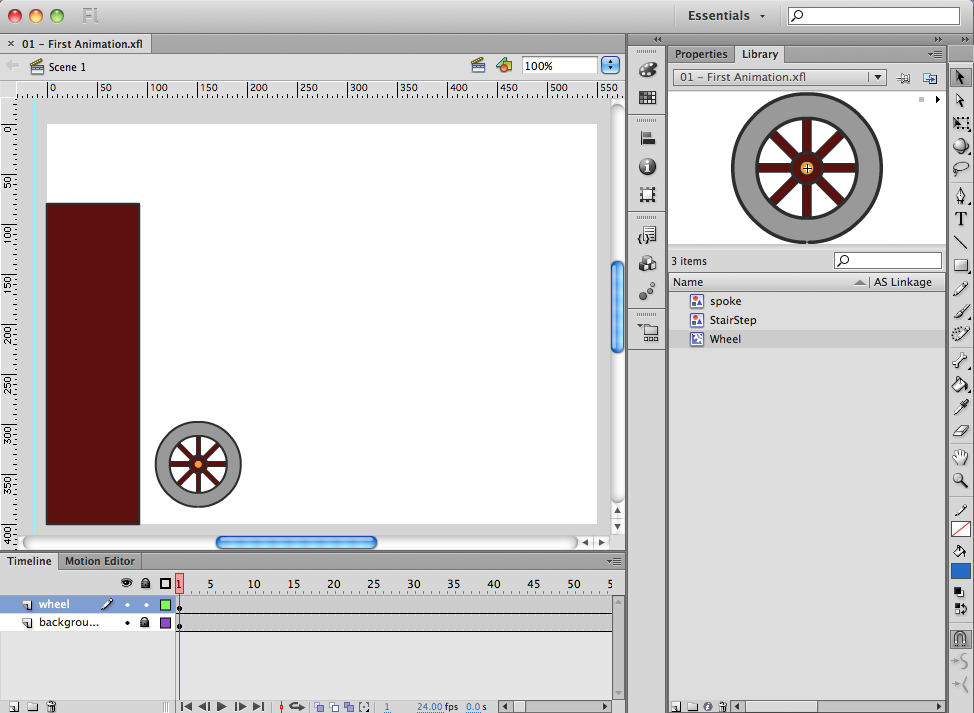

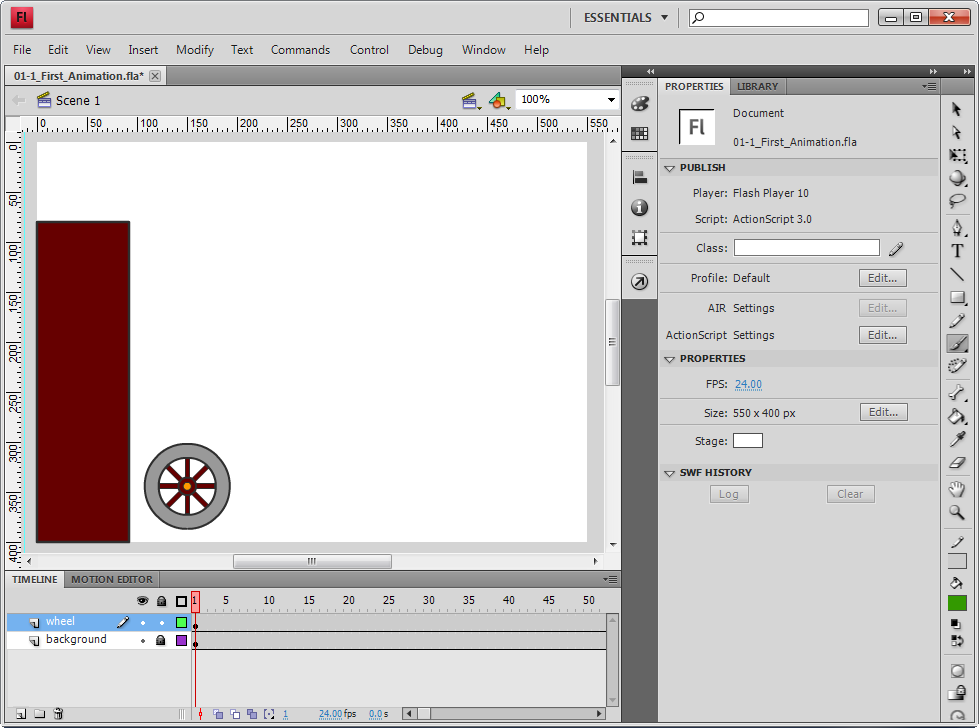

Get the file 01-1_First_Animation.fla and save it on your computer. You may want to create a FlashMM folder in your My Documents or Documents folder to hold your Missing Manual exercises. Launch Flash, and then choose File→Open. When the Open dialog box appears, navigate to the file you just downloaded, and then click Open. When you open a document, the Welcome screen disappears. Flash shows you the animation on the stage, surrounded by the usual timeline, toolbars, and panels. If you’re using the Essentials workspace, it should look like Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-12. After you open the exercise in Flash, your screen should look like this. At the bottom, the timeline shows two layers—one named background and the other, wheel. The stage shows (surprise, surprise) a background and a wheel. To the right, the Properties panel displays the properties for the document.

The Properties panel appears docked to the right side of the stage when you open a new document. As shown in Figure 1-13, it shows the Property settings for objects. Initially, it shows the properties for the Flash document itself. Click another object, such as the wheel, and you see its properties. Why are properties so important? They give you an extremely accurate description of objects. If you need to precisely define a color or the dimensions of an object, the Properties panel is the tool to use. It not only reports the details, but it also gives you the tools to make changes, as shown in this little exercise:

At the top of the Tools panel, click the Selection tool (solid arrow).

As an alternative, press V, the keyboard shortcut for the Selection tool.

Click the white part of the stage.

The Properties panel shows the properties for your Flash document. At the top, you see the word “Document,” and underneath, you see the filename.

Click the triangle button to open the Properties subpanel.

The button works like a toggle to open and close the subpanel. The subpanel displays three settings: FPS (frames per second), Size, and Stage.

Click the white rectangle next to Stage.

A panel opens with color swatches.

Click a color swatch—any color will do.

The background color of the stage changes to the color you chose.

Click the wheel.

Information about the wheel fills the Properties panel. The wheel is a special type of object called a Movie Clip symbol. You’ll learn much more about Movie Clips and other reusable symbols in Chapter 7.

Note

You may notice that you can’t select anything else in this document. That’s because the other objects are in the background layer, which is locked. (For more details on locking layers, see Locking and Unlocking Layers.)

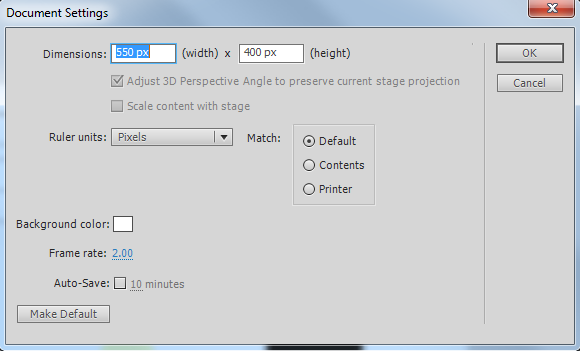

In Flash, the size of your stage is the actual finished size of your animation, so setting its exact dimensions is one of the first things you do when you create an animation, as you’ll see in the next chapter. But you can resize the stage at any time.

Here’s how to change the size of your stage:

With the Selection tool, click on a blank area of the stage (to make sure nothing on the stage is selected).

Alternatively, you can click the Selection tool and then choose Edit→Deselect All.

In the Properties panel, open the Properties subpanel, and then click the Edit button.

The Document Settings window appears, as shown in Figure 1-14. At the top of the window are boxes labeled Dimensions. That’s where you’re going to work your magic.

Figure 1-14. The Document Settings dialog box puts several related settings in one place. At the top are the document’s dimensions. In the lower-left corner are settings for the stage’s background color and the frame rate. Click “Ruler units” to choose among Inches, Points, Centimeters, Millimeters, and Pixels.

Click in the width box (which currently reads “550 px”), and then type 600.

You can change both the width and the height. The changes won’t take place until you click OK. So if you have second thoughts and don’t want to make any changes, then just click Cancel.

Tip

If you want to change the stage back to its original dimensions after you’ve clicked OK, you can do that by choosing Edit→Undo or pressing Ctrl+Z (⌘-Z on a Mac). Undo works like it does in most programs, undoing your last action, and you can press it multiple times to work your way back through your recent actions.

Click OK when you’re done.

When your Flash project gets big or complicated, you may want to focus on just a portion of the stage. If you’ve used other graphics programs—from Windows Paint to iPhoto or Photoshop—there’s not much mystery to the process. In the Tools panel, click the Zoom tool, which looks like a magnifying glass (Figure 1-15). Initially, the Zoom tool shows a + sign, meaning it’s all set to zoom in. Click any spot you want to zoom in on, and you get a closer view. As an alternative, you can click and drag over an area to zoom in with more precision. As you drag, a rectangle appears to mark the area of interest.

Figure 1-15. Choose the Zoom tool and then click the stage to zoom in on your Flash document. Hold the Alt (Option) key down to zoom out. Once you’re zoomed in, you can move around using either the scrollbars or the Hand tool (H).

Using the Zoom tool, you can get so close that you see individual pixels in your artwork. Very handy for some operations. Once you’re zoomed in, you can use the scroll bars at the right and bottom of the stage to reposition the stage in the viewing area. Even easier, choose the Hand tool (H) and then click and drag the stage within the viewing area.

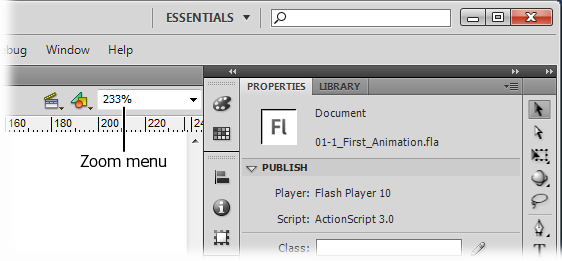

Want to zoom out? Hold down the Alt (Option) key as you use the Zoom tool. Each time you click, you see more and more of the stage. Directly above the stage is the Edit bar. (If you don’t see it, select Window→Toolbars→Edit Bar.) A menu on the Edit bar sets the Magnification or Zoom property as a percentage, as shown in Figure 1-16.

If you’ve followed along in the exercises up to this point, you deserve a taste of the Flash magic to come. Enough studying panels and tools—Flash is an animation program. It’s time to make something move, or more precisely, to make something bounce. With the help of a little feature called Motion Presets, it’s easier than you think:

In the Magnification menu, choose “Fit in Window.”

This gives you a view of the entire stage.

With the Selection tool (V), drag the wheel to the top of the stage.

All the parts of the wheel (tire, spokes, hub) move as a single unit because they’re grouped within a Flash symbol, called a Movie Clip.

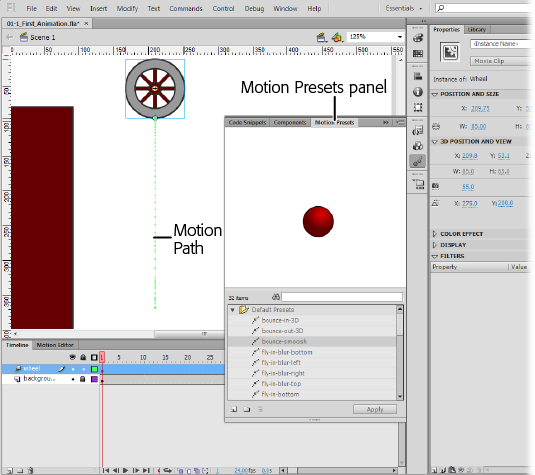

Choose Window→Motion Presets.

A floating panel appears, as shown in Figure 1-17. Motion Presets are covered in detail on Applying Motion Presets, but for this exercise, you just need a couple of basic steps.

Click the triangle next to Default Presets.

The Default Presets folder opens, showing many predesigned motions.

Click the words “bounce-smoosh.”

At the top of the panel, the preview window gives you an idea of how the bounce-smoosh preset works.

Make sure the wheel is selected on the stage and that “bounce-smoosh” is selected in the Motion Presets panel, and then click the Apply button.

A green line appears hanging from the bottom of the wheel. This line is called the motion path, and it shows you how the wheel will move over the course of the animation. In the timeline, the wheel layer turns to blue to indicate that it’s now a motion tween.

Close the Motion Presets panel.

That’s all it takes to animate the wheel, so you might as well close the Motion Presets window. You can always bring it back later if you want to try out some of the other presets on the wheel.

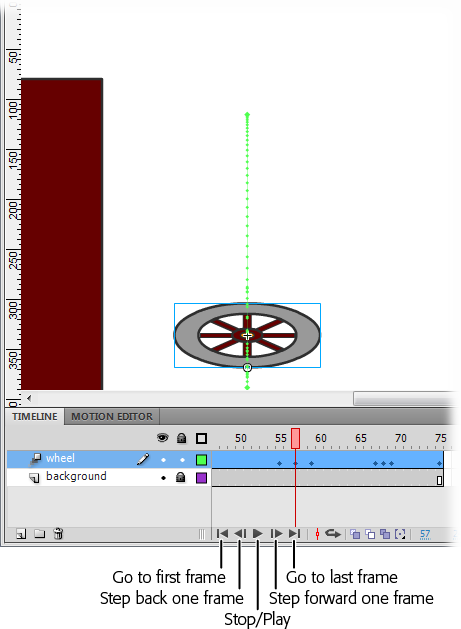

Naturally, after you’ve animated an object in Flash, you want to see the results. You’ll be checking your work frequently, so Adobe makes it easy to play an animation. Just press Enter (Return), and your animation bounces and smooshes as advertised. In the timeline, notice how the playhead moves along frame by frame as your animation plays. You can see your animation at all the different stages by dragging the playhead up and down the timeline—a process sometimes called scrubbing.

New in Flash CS6, the animation controller is fixed to the bottom of the timeline (Figure 1-18). That’s the perfect place because it’s always available.

Saving your work frequently is important in any program, and Flash is no exception. You don’t want to have to go back and recreate that perfect animated sequence because the power went out. The minute you finish a sizable chunk of work, save your Flash file by pressing Ctrl+S (⌘-S). The Save command also appears on the menu bar: File→Save. Both maneuvers save the animation with the current name. So, if after following the exercises in this chapter, you use the Save command, you end up with a single Flash document using the original filename: 01-1_First_Animation.fla.

If you want to save the file under a different name, use Save As or Ctrl+Shift+S (Shift-⌘-S). A standard window opens where you can choose a folder and give your document a name. When you use Save As, you end up with two documents, the original and one saved with the new name. The newly named document is the one that remains open in the Flash workspace.

If you close a document (File→Close) after you’ve made changes, Flash automatically asks if you want to save it. You’re given three options. Choose Save to save your work and close the document. Choose Don’t Save to close the document without saving your work. Choose Cancel if you don’t want to save and don’t want to close the document.

Note

Flash Professional CS6 provides a new life-saving feature for files. When you create a new document you can turn on Auto-Save. This feature saves your document periodically even if you forget. You even get to choose the period. Initially, the Auto-Save period is set to every 10 minutes. To change that, click the number and type a new value.

Get Flash CS6: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.