Chapter 4. Scaling the Incident Response

Incident Response and Escalation

Small incidents with low impact typically require less people and management framework, and perhaps rely more on problem solving by individuals. Large problems with high impact typically require more incident responders, more management framework, more teamwork, more tasks to complete and track, more stress, and more business impact to consider. These larger incidents generally require a robust management framework to stay organized and a stronger Incident Commander to keep the effort moving forward in a clear and purposeful manner.

There is no perfect management formula for either situation and no hard-and-fast rules. It’s up to each Incident Commander to create the right mixture of command and framework to create the most effective incident resolution environment, which is matched to the size and scope of the incident. Part of being a good Incident Commander is the ability to know how to expertly mix the elements of command, framework, and problem-solving.

Span of Control

As humans, we all have limits around how much information we can process at any given moment or how much attention we can pay to competing conversations or tasks, especially under stress. In peacetime, multitasking is commonplace. In wartime, incident responders should be mindful of not getting overwhelmed with too much data, too many simultaneous conversations, or too many tasks to complete in a compressed time frame. It is critical to recognize your limits and the limits of others, and not stretch to the point of breaking, especially when managing people under stress during an incident.

Span of control is the maximum number of people that one person can manage. Typically, that number is 5–7 people. Keeping an acceptable span of control ensures unity of command, or clear lines of reporting authority. When 30 people join an incident conference call bridge, with or without a defined leader, the conversation can quickly degrade, become unproductive, and lose focus, which wastes time that can never be recovered.

In simple terms, span of control is a management tactic for the Incident Commander. It’s used when there is a need to organize many incident responders in a way that maintains control of the tasks being assigned and the discussions that must take place. It’s breaking down a large set of tasks into smaller, more manageable activities and delegating the work in a way that allows the work to be tracked and managed efficiently.

This is not to say that the recommended span of control of 5–7 direct reports must never be violated. Remember that incidents are dynamic and can change, often quite rapidly and dramatically, but don’t get caught with too large a span of control.

Let’s review the concept of span of control in action with this example, using the CAN report format:

- Conditions

-

-

System performance has slowed after a recent software change in a critical application

-

The cause is unknown

-

- Actions

-

-

Level 1 help desk has determined the problem is beyond their scope and escalated to the IRT

-

- Needs

-

-

IRT to investigate

-

Note

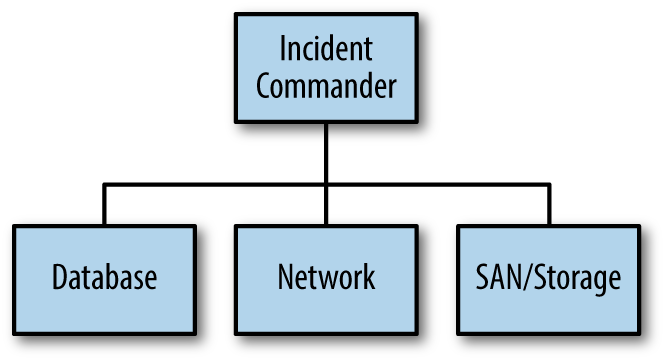

Again, in low-impact issues, it may be as basic as an Incident Commander leading a small group of only two or three incident responders, as seen in Figure 4-1. In this illustration, the organizational chart represents a small group of first responders (SMEs) to arrive on an incident conference call bridge: one DBA, one network engineer, a SAN/Storage engineer, and the Incident Commander.

As with any incident, the Incident Commander role is initially filled by the first qualified IC on the bridge. However, keep in mind that the function of Command may be transferred at any time to anyone for any reason as long as that person is qualified to fill the role of Incident Commander.

Even for this simple seeming incident response (low-severity, noncomplex), the position of Incident Commander should be established. Again, looking toward the fire service as a guide, you could hear something like this radio transmission on a regular basis, even on what might be considered a routine incident: “Engine 2 on scene of a two-vehicle traffic accident. Looks like all parties are out of the vehicles. Engine 2 establishing Oak Street Command.” There are certainly variations on the words used, but the point is that even though this incident seems like a small green-yellow box issue, the fire service does it that way because it is the way, and when that same fire engine pulls up on a large incident, the process of establishing command is familiar and automatic.

Figure 4-1. Simple command structure for a low-severity issues

You’ll also notice in Figure 4-1 that the boxes aren’t identified by the name of the person filling the position, rather only the job functions are named: IC, Database, Network, and SAN/Storage. Going back to the example just given about the fire service, the company officer (leader of the team) on Engine 2 didn’t say, “Frank, Pete, Bill, and Kathy are on scene.” They were identified by their function, which in this case it is a team function called Engine 2. As another example, the big ladder trucks you see at a fire represent a specific function, just as the hazardous materials response unit is a function, and so is a technical rescue team. To that point, the process of establishing command and directing resources by job function (SMEs) instead of by name of person allows for the organizational chart to grow quickly and clearly, even if the person filling the function changes for some reason. The function is the constant. The specific person who fills it may vary day to day, and even during an incident.

If more than one DBA is needed in the example shown in Figure 4-1, a database group can be created and the Incident Commander will only need to communicate with the leader of the database function (Database Group Leader, or DGL) without keeping track of the multiple individuals assigned to it. If your organization is small and everyone knows each other, this may seem ridiculous, but when the SME pool is large or spread around the globe, it’s much clearer to keep track of your SMEs by function rather than name.

To continue with the example shown in Figure 4-1, assume that after a few minutes of discussion, three more DBAs from another time zone join the incident conference call bridge. The Incident Commander acknowledges the new incident responders that joined the bridge and the ensuing conversation might sound like this:

SME: “Hi this is Allen from database.”

SME: “Kelly just joined as well.”

Incident Commander: “Hi, Allen. This is Ben. I’m the Incident Commander and we are working a SEV 1. Thanks for joining. I also heard Kelly joined.”

SME Kelly: “Yes, I’m a DBA in Sydney, Australia. I’m here with James as well.”

Incident Commander: “Copy that, sorry to wake you at this hour, but we need your help. I’m in the middle of a conversation with the SAN/Storage engineer and will give you a CAN report shortly. Stand by for now.”

SME: “Copy that. Stand by.”

SME Kelly with James: “Okay.”

In this quick exchange, the Incident Commander has laid out the rules of engagement for the SMEs to join the bridge, then must decide the timing of giving updates and/or engaging the SMEs. If an important conversation is in progress and a new person joins, the Incident Commander may wait to acknowledge the SME in favor of not breaking the flow of the conversation. There are no set rules on this. It is up to the Incident Commander how to manage the flow of incident responders arriving on the incident conference call bridge.

Additionally, some IRTs use a status page or some other way to electronically capture events and make the information available to all incident responders. This is an efficient way to provide status updates and up-to-the-minute information about the incident response. Absent that, however, the Incident Commander can provide CAN reports at regular intervals to keep everyone informed.

Let’s fast forward and assume that our example of an incident response scenario is quickly increasing in severity and the number of incident responders has grown to nine. To prevent chaos on the bridge, the Incident Commander would need to maintain span of control. Let’s assume that the incident is identified as a database issue and there is robust conversation occurring between the DBAs. Since there are now five DBAs on the call, and depending on what is being discussed on the bridge, it might make sense for the Incident Commander to:

-

Create a database group.

-

Assign one of the DBAs to the role of the Database Group Leader (DGL).

-

Direct them to set up another incident conference bridge and move their conversations to that bridge.

-

Ask that only the DGL report back to the Incident Commander and/or answer for the group.

The DGL may or may not be a peacetime database manager or even the most experienced DBA. In fact, it’s totally the Incident Commander’s choice (with DBA input and what’s right for the situation), but the DBAs need to support their DGL.

The newly appointed DGL should take the following actions:

-

Move the database group from the main incident conference call bridge to a database-group bridge.

-

Lead the discussions on the database-group bridge.

-

Assign tasks to DBAs in the database group and facilitate discussions.

-

Report back to the Incident Commander on the main incident conference call bridge.

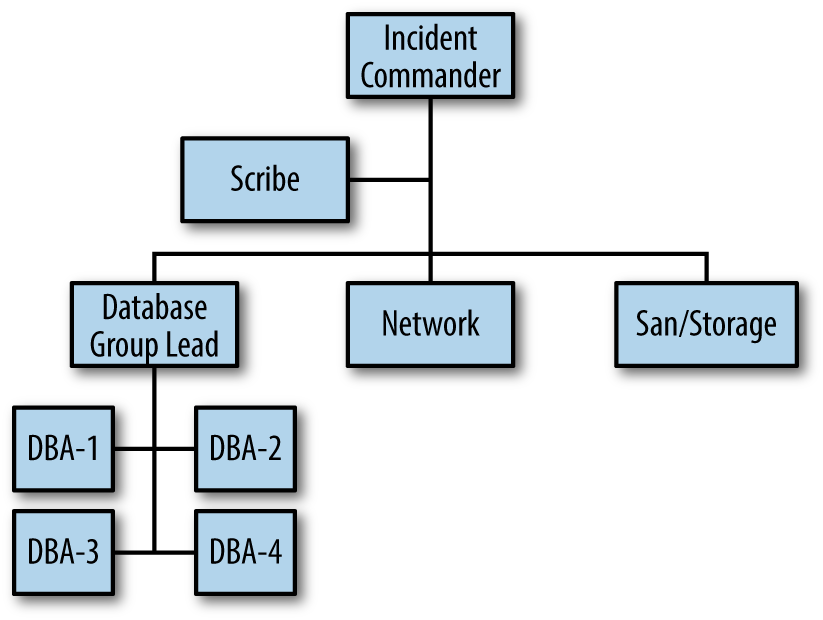

Figure 4-2 illustrates the organizational chart representing the newly formed database group. You can see that the Incident Commander is mindful of span of control by grouping the DBAs together.

Note

The Incident Commander can be creative with the command structure, but the idea is to delegate or chunk off the tasks in a way that keeps the number of people reporting to any other person within the 5–7 span of control range.

It’s appropriate for the DGL to inform the Incident Commander of the results of the database group work and or recommendations/actions. In that discussion, the Incident Commander should direct questions to the DGL. Importantly, the DGL is the only person who speaks for the database group. If the database group is disbanded after the tasks are completed, everyone from the database group, including the DGL, are available for another set of tasks.

This is a simple illustration of the point, but with the modular nature of IMS, an Incident Commander can build out a structure to streamline and monitor/control the response more effectively. By grouping resources, appointing group leaders (GL), and assigning tasks by function, communication is direct and easier to follow. If another group of experts were needed, the Incident Commander could create another group with another name, appoint a leader, outline tasks with a timeline, and expect a report from the GL on the incident conference call bridge.

Figure 4-2. The incident organizational chart for an expanded incident

Additionally, you see the position of scribe (SitStat) is added to the organizational chart. It’s also called SitStat because it’s the function that keeps the situational status at all times during the incident. A scribe (whether it is a person performing the task or perhaps automated in some way) is useful to assist the Incident Commander with documenting: the incident responders; incident timeline; assignments made by function with time deadlines; and actions taken. Not all organizations have the luxury of a large IRT or a large pool of SMEs, so this position may not be realistic for your IRT. If not, scribing should still be done, but it gets done by the Incident Commander. You may be documenting the response electronically, which is certainly useful, but keep in mind that the scribe position is a great way for junior members of the IRT to gain experience and observe a more senior member handling an incident response. Additionally, scribing may be viewed as a mundane task, when in reality it is quite important in terms of keeping an accurate timeline of the incident and becomes the basis for an After Action Review (AAR).

Note

The scribe (SitStat) position is shown here as a function to be filled and doesn’t count against the span of control for the Incident Commander. It is a supportive role and not active in problem-solving effort.

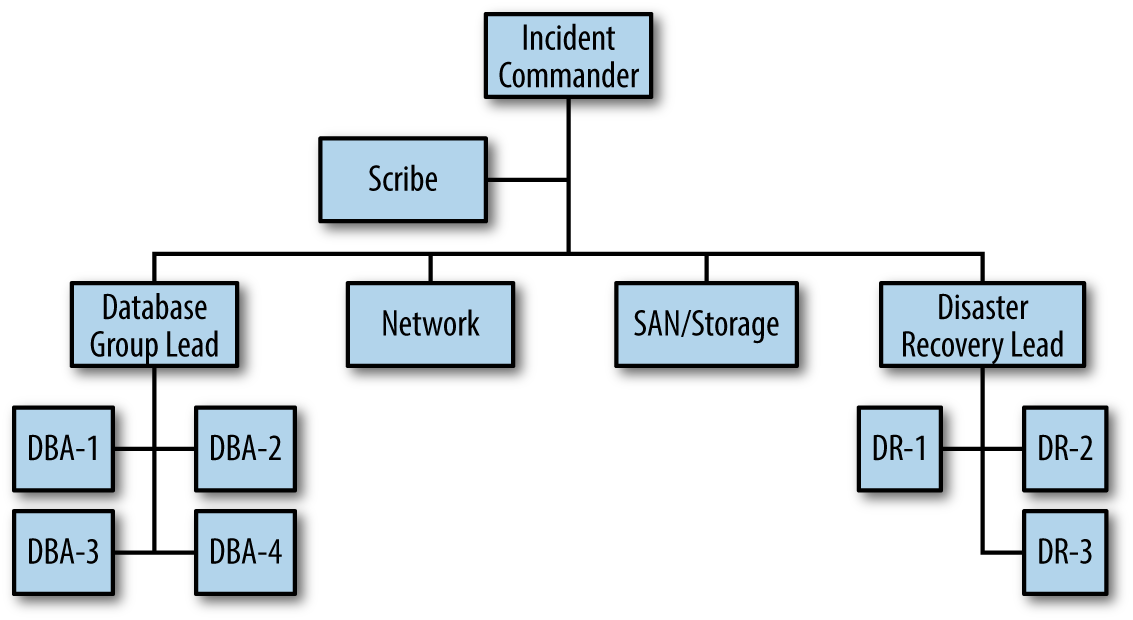

Figure 4-3 represents a possible way the example in Figure 4-2 might escalate with even more incident responders, still maintaining a proper span of control.

At this point, it’s useful to define the term escalate. In IT, to escalate has two separate, but interrelated meanings: 1) to take an issue to a higher-ranking manager for a decision; 2) in the event a person identified as a primary on-call resource does not respond within a time frame, call the secondary or tertiary resource. Here’s a typical dialogue for the first definition: “This is a network decision I don’t have the authority to make, so I’m going to escalate to my network manager to make the call.” Here’s a typical dialogue for the second definition: “The primary network on-call was paged 15 minutes ago and hasn’t joined the incident conference call bridge, so I’m going to escalate to the secondary on-call so we can get someone from network onto the bridge.”

In the fire service, to escalate has a very different definition: to request more or different resources as conditions change on an incident. Here’s a typical fire service dialogue from the Incident Commander: “Fire has spread to the second floor, dispatch a second alarm and two more ambulances.”

We recommend using the fire service definition of escalate in IT. As we described earlier, MTTA is the only part of the incident response that the IRT can truly control. In the second definition of escalate in IT, a primary on-call incident responder is not responding, which is hindering the IRT from moving forward to resolve the incident, and wasting valuable time. As we discussed earlier, if an incident responder is available, they are in a position of operational readiness, will join an incident conference call bridge with a sense of urgency, and arrive able to complete assignments from the Incident Commander.

We had a client ask us “How does the fire department deal with a fire engine that is dispatched to a scene but doesn’t show up?” We were flabbergasted by the question, because that situation never happens in the fire department! To be sure, fire engines get flat tires or break down and can’t respond, but if they are available for incident response, they are in a position of operational readiness, will respond with a sense of urgency, and will arrive able to complete assignments from the Incident Commander. The nonresponsive primary on-call issue should be discussed with their manager off the incident conference call bridge to prevent this from occurring again.

Back to our example: The incident expanded quickly and the Incident Commander chose to increase the SEV level and call for the different resources, “I’m escalating this to a SEV 1. Let’s get the Disaster Recovery Team (DR) team activated.”

Figure 4-3. The incident organizational chart showing a greater expansion in the incident

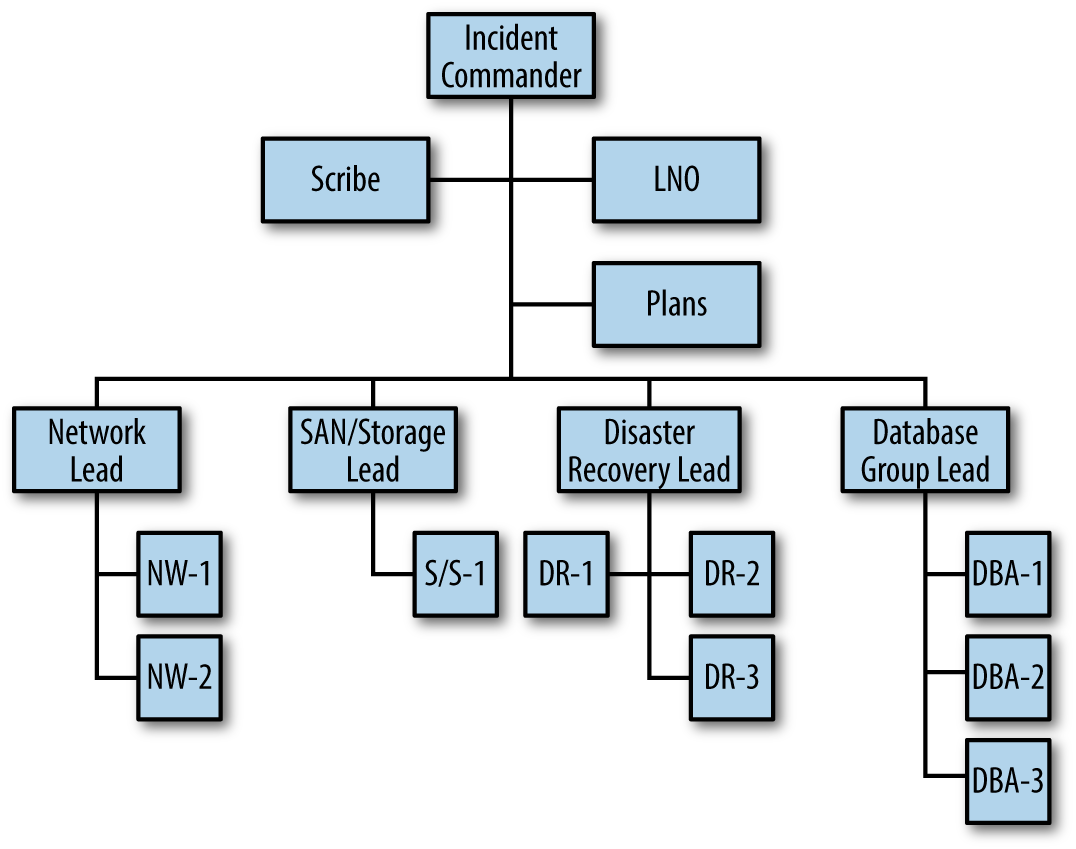

When the DR team arrives on the bridge, the organizational chart would change accordingly. Again, more incident responders joined, but the span of control of the Incident Commander remained within an acceptable range. Figure 4-4 represents a further expansion of the IMS framework. Don’t worry about understanding the job functions in terms of their specific duties for this scenario. Rather, focus on the organizational chart and how an expanding incident can accommodate a large number of incident responders by assigning groups. Functions like plans, liaison officer, and scribe are called command staff functions (assigned to assist the Incident Commander directly) and are not counted against the span of control. Again, the Incident Commander can configure the organizational chart to keep control over the resource pool and maintain an effective span of control.

Figure 4-4. IMS organization chart for an escalating incident. This level of response may be indicated for red-box incidents.

Transfer of Command

If incidents go on for an extended period of time, command (as well as any of the other functions) can be transferred to another qualified member of the IRT. The transfer should be an orderly process and announced on the incident conference bridge. So, when is this done? Transferring command or any other job function can happen anytime during an incident response, but it most commonly occurs when:

-

There is a natural break in a work period, such as shift changes or global handoffs between teams.

-

An Incident Commander is fatigued and it’s in the best interest of the incident to get a well-rested person into the position.

-

An Incident Commander may be struggling and a more qualified person is available.

-

For business reasons, a more senior or higher-ranking peacetime person should be leading the incident response.

As mentioned, the off-going Incident Commander should announce to the group that command is being transferred and introduce the new oncoming Incident Commander to the group. Prior to that, the off-going Incident Commander should provide a CAN report to the on-coming Incident Commander off the incident conference call bridge in order to bring that person up to speed on the current conditions and activities on the bridge. The reason this is done off the incident conference call bridge is so that the two Incident Commanders can have a candid conversation about the incident response efforts. If there is a problem SME that the off-going Incident Commander was not able to handle, they can discuss a strategy to deal with this situation. The off-going Incident Commander may have wanted to go another direction but the team was resistive. The new Incident Commander can come in and present the new plan and move it forward. When a new direction is needed, a change in Incident Commanders can facilitate this redirection.

Summary

In the world of public safety, some incidents are big and complex and require a lot of people to be coordinated and managed—like the World Trade Center incident on 9/11. Some incidents are relatively small and can be handled in most cases by a small team of incident responders—like a small house fire. A routine medical call requires a smaller incident response and would typically be handled by a smaller team of medical and fire personnel.

In IT, the IRT may be called upon to solve and recover from large, complex incidents, such as a widespread, persistent DDoS attack. High SEV incidents might require the collective problem-solving skills of network engineers, DBAs, key peacetime executives, outside vendors, and perhaps even a disaster recovery team, which may result in dozens of people cycling on and off an incident conference call bridge. Conversely, a handful of engineers may be working a problem with a single customer having an issue with an application.

-

The best way to build skill and proficiency in incident management is to regularly use IMS for green and yellow box issues, not just on large, complex red- and black-box incidents.

-

Each Incident Commander should strive to find the right mixture of command, framework, and problem-solving effort to create the most effective incident resolution environment, matched to the size and scope of the incident.

-

Span of control is the maximum number of people that one person can manage. Typically, that number is 5–7 people.

-

The function of Command (or any other job function on a response) may be transferred at any time to anyone for any reason as long as that person is qualified to fill the role.

-

Job functions during an incident response are constant. The people who fill the function may vary.

Get Incident Management for Operations now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.