Schema-driven XML editing describes the

ability to give the user choices according to the document context

they are in, guiding the editing process according to constraints in

the schema, and keeping them from creating invalid documents. For

example, in the context of an element whose type definition consists

of an exclusive xsd:choice group, the user could

be prompted to choose among the valid element choices in that context

but disallowed from selecting more than one of the choices. This kind

of guided editing perfectly describes the aim of Smart Documents,

introduced in Chapter 5.

Unfortunately, Word does not provide any sort of robust, schema-driven editing functionality out of the box. (Once again, check out InfoPath in Chapter 10, if that’s what you need.) However, there is some limited schema-aware editing functionality available in Word, specifically through the XML Structure task pane and the Attributes dialog. We’ll examine those now and discuss how they can still be useful.

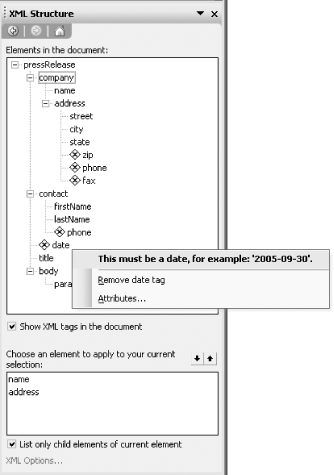

The XML Structure task pane is available whenever a document has a schema attached to it. It provides a tree view of the custom XML elements in the merged instance document. Figure 4-19 shows the XML Structure task pane for our press release template.

The tree view shows the local name of each custom XML element in the

document. The small yellow “X”

icons represent schema validation errors. Since this document is our

empty press release template, a number of elements are not yet valid,

because they are empty. Specifically, the zip,

phone, fax,

phone, and date elements are

all invalid. You can see the specific validation error by

right-clicking the element name. In this case, the user has

right-clicked “date,” yielding a

pop-up message showing the details of the problem.

By clicking on different parts of the tree, you can jump to different

parts of the document. Though the main pane isn’t

shown here, you can determine that the cursor is currently inside the

company element, because

“company” is highlighted in the XML

Structure task pane.

Clicking the “Show XML tags in the document” checkbox is equivalent to pressing Ctrl-Shift-X; it toggles the option on or off.

Finally, the list at the bottom of the task pane gives you some

choices of elements to insert into the document at the current cursor

position or to “apply” to your

current selection in the document. If you click one of these names,

Word will insert a new instance of that element into the document. If

the “List only child elements of current

element” checkbox is checked (which it is, by

default), the list will contain only the possible children of the

current element, according to the schema. If it is unchecked,

you’ll get a list of all element names declared in

the schema. In this case, since the checkbox is checked and the

current context is the company element, only the

name and address elements are

listed. The list does not change according to what elements are

already present in the document or what order

they’re in; it’s not that smart. In

other words, it won’t keep you from making invalid

insertions.

Thus, the XML Structure task pane tells you if something’s wrong, but it doesn’t keep you from doing something wrong in the first place. In that respect, it scores a 100% on validation, and something far less than 100% on schema-driven editing. So, if the XML Structure task pane is just a poor man’s version of schema-driven XML editing, what good is it? If it’s not user-friendly and doesn’t keep users from getting into trouble, why is it a part of the Word application at all? Fortunately, there is a good answer to this question. The XML Structure task pane, rather than being primarily a tool for end users, is an excellent tool for developers in building custom XML editing solutions for Word. In fact, the XML Structure task pane was used heavily in the creation of our press release template. See Section 4.13 later in this chapter.

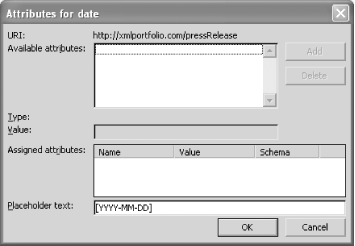

You

may have noticed that our press release schema (conveniently) does

not declare any attributes. There is a reason for this. Without using

Smart Documents, Word provides only one way to directly edit custom

XML attributes: the Attributes dialog. You can open the Attributes

dialog either by right-clicking an element in the XML Structure task

pane or by right-clicking the custom XML tag itself (assuming

“Show XML tags” is turned on).

Figure 4-20 shows the Attributes dialog for the

date element in our press release template.

Since our schema does not declare any attributes for the

date element (or any other element for that

matter), the list of “Available

attributes” is empty. If there were legal attributes

for the date element, then the user could select

one from the list, enter its value in the Value text box, and click

the Add button. The attribute would then be added to the

“Assigned attributes” list, and

would be added as a normal XML attribute to the start tag of the

date element in the underlying WordprocessingML

representation.

The Attributes dialog performs one other function; it lets you

specify what the placeholder text for a particular element instance

should be. In this case, the placeholder text for the

date element is [YYYY-MM-DD].

While this feature may seem out of place in the Attributes dialog, in

a certain sense it is appropriately positioned, because the

underlying representation of placeholder text (as we saw in Example 4-4) is an attribute, namely the

w:placeholder attribute. In any case, this is not

something the end user would normally edit. This adds support to the

argument that it’s unreasonable to force users to

edit attributes using the Attributes dialog.

Like the XML Structure task pane, the Attributes dialog may not be terribly useful for end users, but it can be handy for developers in creating custom XML editing solutions, at least insofar as it allows you to insert placeholder text via the Word UI, as you are constructing your template. See Section 4.13 later in this chapter.

As implied above, the use of Smart Documents could allow users to

edit attributes without using the generic Attributes dialog. However,

there is also a way to enable users to edit attribute values without

resorting to Smart Document programming. It is true that the

Attributes dialog is the only way to directly

edit custom XML attributes in Word, but by using both an

onload

stylesheet and an onsave stylesheet, you can

enable users to indirectly edit attributes

without using the Attributes dialog. Here’s how it

works. First, the onload XSLT stylesheet

translates the attributes to elements, so that users can edit them as

elements. Then, the onsave stylesheet translates

them back to attributes when the user saves the document. In this

approach, the schema in the schema library does not necessarily

reflect the actual structure of the XML documents being edited, but

rather an intermediate structure that exists only for the purpose of

editing within Word. Such restructuring is a typical use case for

onsave XSLT transformations, which

we’ll discuss in “The

`Apply Custom Transform’ Document

Option” later in this chapter.

Get Office 2003 XML now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.