The next step after building and installing a mod_perl-enabled Apache server is to configure it. This is done in two distinct steps: getting the server running with a standard Apache configuration, and then applying mod_perl-specific configuration directives to get the full benefit out of it.

For readers who haven’t previously been exposed to the Apache web server, our discussion begins with standard Apache directives and then continues with mod_perl-specific material.

The startup.pl file can be used in many ways to improve performance. We will talk about all these issues later in the book. In this chapter, we discuss the configuration possibilities that the startup.pl file gives us.

<Perl> sections are a great time saver if

you have complex configuration files. We’ll talk

about <Perl> sections in this chapter.

Another important issue we’ll cover in this chapter is how to validate the configuration file. This is especially important on a live production server. If we break something and don’t validate it, the server won’t restart. This chapter discusses techniques to prevent validation problems.

At the end of this chapter, we discuss various tips and tricks you may find useful for server configuration, talk about a few security concerns related to server configuration, and finally look at a few common pitfalls people encounter when they misconfigure their servers.

Apache configuration can be confusing. To minimize the number of things that can go wrong, it’s a good idea to first configure Apache itself without mod_perl. So before we go into mod_perl configuration, let’s look at the basics of Apache itself.

Prior to Version 1.3.4, the default Apache installation used three configuration files: httpd.conf, srm.conf, and access.conf. Although there were historical reasons for having three separate files (dating back to the NCSA server), it stopped mattering which file you used for what a long time ago, and the Apache team finally decided to combine them. Apache Versions 1.3.4 and later are distributed with the configuration directives in a single file, httpd.conf . Therefore, whenever we mention a configuration file, we are referring to httpd.conf.

By default, httpd.conf is installed in the conf directory under the server root directory. The default server root is /usr/local/apache/ on many Unix platforms, but it can be any directory of your choice (within reason). Users new to Apache and mod_perl will probably find it helpful to keep to the directory layouts we use in this book.

There is also a special file called .htaccess , used for per-directory configuration. When Apache tries to access a file on the filesystem, it will first search for .htaccess files in the requested file’s parent directories. If found, Apache scans .htaccess for further configuration directives, which it then applies only to that directory in which the file was found and its subdirectories. The name .htaccess is confusing, because it can contain almost any configuration directives, not just those related to resource access control. Note that if the following directive is in httpd.conf:

<Directory />

AllowOverride None

</Directory>Apache will not look for .htaccess at all unless

AllowOverride

is set to a value other than

None in a more specific

<Directory> section.

.htaccess can be renamed by using the

AccessFileName

directive. The following example

configures Apache to look in the target directory for a file called

.acl instead of .htaccess:

AccessFileName .acl

However, you must also make sure that this file can’t be accessed directly from the Web, or else you risk exposing your configuration. This is done automatically for .ht* files by Apache, but for other files you need to use:

<Files .acl>

Order Allow,Deny

Deny from all

</Files>Another often-mentioned file is the startup file, usually named startup.pl . This file contains Perl code that will be executed at server startup. We’ll discuss the startup.pl file in greater detail later in this chapter, in Section 4.3.

Beware of editing httpd.conf without understanding all the implications. Modifying the configuration file and adding new directives can introduce security problems and have performance implications. If you are going to modify anything, read through the documentation beforehand. The Apache distribution comes with an extensive configuration manual. In addition, each section of the distributed configuration file includes helpful comments explaining how each directive should be configured and what the default values are.

If you haven’t moved Apache’s directories around, the installation program will configure everything for you. You can just start the server and test it. To start the server, use the apachectl utility bundled with the Apache distribution. It resides in the same directory as httpd, the Apache server itself. Execute:

panic% /usr/local/apache/bin/apachectl start

Now you can test the server, for example by accessing http://localhost/ from a browser running on the same host.

A basic setup requires little configuration. If you moved any directories after Apache was installed, they should be updated in httpd.conf. Here are just a couple of examples:

ServerRoot "/usr/local/apache" DocumentRoot "/usr/local/apache/docs"

You can change the port to which the server is bound by editing the

Port directive. This example sets the port to 8080

(the default for the HTTP protocol is 80):

Port 8080

You might want to change the user and group names under which the server will run. If Apache is started by the user root (which is generally the case), the parent process will continue to run as root, but its children will run as the user and group specified in the configuration, thereby avoiding many potential security problems. This example uses the httpd user and group:

User httpd Group httpd

Make sure that the user and group httpd already exist. They can be created using useradd(1) and groupadd(1) or equivalent utilities.

Many other directives may need to be configured as well. In addition

to directives that take a single value, there are whole sections of

the configuration (such as the <Directory>

and <Location> sections) that apply to only

certain areas of the web space. The httpd.conf

file supplies a few examples, and these will be discussed shortly.

Let’s discuss the basics of the

<Directory>,

<Location>, and

<Files> sections. Remember that there is

more to know about them than what we list here, and the rest of the

information is available in the Apache documentation. The information

we’ll present here is just what is important for

understanding mod_perl configuration.

Apache considers directories and files on the machine it runs on as resources. A particular behavior can be specified for each resource; that behavior will apply to every request for information from that particular resource.

Directives in

<Directory>

sections apply to specific directories on the host machine, and those

in

<Files>

sections apply only to specific files (actually, groups of files with

names that have something in common).

<Location>

sections

apply to specific URIs. Locations are given relative to the document

root, whereas directories are given as absolute paths starting from

the filesystem root (/). For example, in the

default server directory layout where the server root is

/usr/local/apache and the document root is

/usr/local/apache/htdocs, files under the

/usr/local/apache/htdocs/pub directory can be

referred to as:

<Directory /usr/local/apache/htdocs/pub> </Directory>

or alternatively (and preferably) as:

<Location /pub> </Location>

Exercise caution when using <Location> under

Win32. The Windows family of operating systems are case-insensitive.

In the above example, configuration directives specified for the

location /pub on a case-sensitive Unix machine

will not be applied when the request URI is

/Pub. When URIs map to existing files, such as

Apache::Registry scripts, it is safer to use the

<Directory> or

<Files> directives, which correctly

canonicalize filenames according to local filesystem semantics.

It is up to you to decide which directories on your host machine are mapped to which locations. This should be done with care, because the security of the server may be at stake. In particular, essential system directories such as /etc/ shouldn’t be mapped to locations accessible through the web server. As a general rule, it might be best to organize everything accessed from the Web under your ServerRoot, so that it stays organized and you can keep track of which directories are actually accessible.

Locations do not necessarily have to refer to existing physical directories, but may refer to virtual resources that the server creates upon a browser request. As you will see, this is often the case for a mod_perl server.

When a client (browser) requests a resource (URI plus optional arguments) from the server, Apache determines from its configuration whether or not to serve the request, whether to pass the request on to another server, what (if any) authentication and authorization is required for access to the resource, and which module(s) should be invoked to generate the response.

For any given resource, the various sections in the configuration may

provide conflicting information. Consider, for example, a

<Directory> section that specifies that

authorization is required for access to the resource, and a

<Files> section that says that it is not. It

is not always obvious which directive takes precedence in such cases.

This can be a trap for the unwary.

Scope: Can appear in server and virtual host configurations.

<Directory>

and

</Directory> are used to enclose a group

of

directives that will apply to only the named directory and its

contents, including any subdirectories. Any directive that is allowed

in a directory context (see the Apache documentation) may be used.

The path given in the <Directory> directive

is either the full path to a directory, or a string containing

wildcard characters (also called globs). In the

latter case, ? matches any single character,

* matches any sequence of characters, and

[ ] matches character ranges. These are similar to

the wildcards used by sh and similar shells. For

example:

<Directory /home/httpd/docs/foo[1-2]>

Options Indexes

</Directory>will match /home/httpd/docs/foo1 and

/home/httpd/docs/foo2. None of the wildcards

will match a / character. For example:

<Directory /home/httpd/docs>

Options Indexes

</Directory>matches /home/httpd/docs and applies to all its subdirectories.

Matching a regular expression is done by using the

<DirectoryMatch regex> ...

</DirectoryMatch> or <Directory

~ regex> ... </Directory> syntax. For example:

<DirectoryMatch /home/www/.*/public>

Options Indexes

</DirectoryMatch>will match /home/www/foo/public but not

/home/www/foo/private. In a regular expression,

.* matches any character (represented by

.) zero or more times (represented by

*). This is entirely different from the

shell-style wildcards used by the

<Directory> directive. They make it easy to

apply a common configuration to a set of public directories. As

regular expressions are more flexible than globs, this method

provides more options to the experienced user.

If multiple (non-regular expression)

<Directory> sections match the directory (or

its parents) containing a document, the directives are applied in the

order of the shortest match first, interspersed with the directives

from any .htaccess files. Consider the following

configuration:

<Directory />

AllowOverride None

</Directory>

<Directory /home/httpd/docs/>

AllowOverride FileInfo

</Directory>Let us detail the steps Apache goes through when it receives a request for the file /home/httpd/docs/index.html:

Apply the directive

AllowOverride None(disabling .htaccess files).Apply the directive

AllowOverride FileInfofor the directory /home/httpd/docs/ (which now enables .htaccess in /home/httpd/docs/ and its subdirectories).Apply any directives in the group

FileInfo, which control document types (AddEncoding,AddLanguage,AddType, etc.—see the Apache documentation for more information) found in /home/httpd/docs/.htaccess.

Scope: Can appear in server and virtual host configurations, as well as in .htaccess files.

The <Files>

directive provides access control by

filename and is comparable to the

<Directory> and

<Location> directives.

<Files> should be closed with the

corresponding </Files>. The directives

specified

within this section will be applied to any object with a basename

matching the specified filename. (A basename is the last component of

a path, generally the name of the file.)

<Files> sections are processed in the order

in which they appear in the configuration file, after the

<Directory> sections and

.htaccess files are read, but before

<Location> sections. Note that

<Files> can be nested inside

<Directory> sections to restrict the portion

of the filesystem to which they apply. However,

<Files> cannot be nested inside

<Location> sections.

The filename argument should include a filename or a wildcard string,

where ? matches any single character and

* matches any sequence of characters, just as with

<Directory> sections. Extended regular

expressions can also be used, placing a tilde character

(~) between the directive and the regular

expression. The regular expression should be in quotes. The dollar

symbol ($) refers to the end of the string. The

pipe character (|) indicates alternatives, and

parentheses (()) can be used for grouping. Special

characters in extended regular expressions must be escaped with

backslashes (\). For example:

<Files ~ "\.(pl|cgi)$">

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Registry

Options +ExecCGI

</Files>would match all the files ending with the .pl or

.cgi extension (most likely Perl scripts).

Alternatively, the <FilesMatch regex> ...

</FilesMatch> syntax can be used.

Scope: Can appear in server and virtual host configurations.

The <Location>

directive

provides for directive scope limitation by URI. It is similar to the

<Directory> directive and starts a section

that is terminated with the </Location>

directive.

<Location> sections are processed in the

order in which they appear in the configuration file, after the

<Directory> sections,

.htaccess files, and

<Files> sections have been interpreted.

The <Location> section is the directive that

is used most often with mod_perl.

Note that URIs do not have to refer to real directories or files

within the filesystem at all; <Location>

operates completely outside the filesystem. Indeed, it may sometimes

be wise to ensure that <Location>s do not

match real paths, to avoid confusion.

The URI may use wildcards. In a wildcard string, ?

matches any single character, * matches any

sequences of characters, and [ ] groups characters

to match. For regular expression matches, use the

<LocationMatch regex> ...

</LocationMatch> syntax.

The <Location> functionality is especially

useful when combined with the SetHandler

directive. For example, to enable server status requests (via

mod_status) but allow them only from browsers at

*.example.com, you might use:

<Location /status>

SetHandler server-status

Order Deny,Allow

Deny from all

Allow from .example.com

</Location>As you can see, the /status path does not exist on the filesystem, but that doesn’t matter because the filesystem isn’t consulted for this request—it’s passed on directly to mod_status.

When configuring the server, it’s important to understand the order in which the rules of each section are applied to requests. The order of merging is:

<Directory>(except for regular expressions) and .htaccess are processed simultaneously, with the directives in .htaccess overriding<Directory>.<DirectoryMatch>and<Directory ~ >with regular expressions are processed next.<Files>and<FilesMatch>are processed simultaneously.<Location>and<LocationMatch>are processed simultaneously.

Apart from <Directory>, each group is

processed in the order in which it appears in the configuration

files. <Directory>s (group 1 above) are

processed in order from the shortest directory component to the

longest (e.g., first / and only then

/home/www). If multiple

<Directory> sections apply to the same

directory, they are processed in the configuration file order.

Sections inside <VirtualHost> sections are

applied as if you were running several independent servers. The

directives inside one <VirtualHost> section

do not interact with directives in other

<VirtualHost> sections. They are applied

only after processing any sections outside the virtual host

definition. This allows virtual host configurations to override the

main server configuration.

If there is a conflict, sections found later in the configuration file override those that come earlier.

Let’s

say that you want all files to be

handled the same way, except for a few of the files in a specific

directory and its subdirectories. For example, say you want all the

files in /home/httpd/docs to be processed as

plain files, but any files ending with .html and

.txt to be processed by the content handler of

the Apache::Compress module (assuming that you are

already running a mod_perl server):

<Directory /home/httpd/docs>

<FilesMatch "\.(html|txt)$">

PerlHandler +Apache::Compress

</FilesMatch>

</Directory>The + before Apache::Compress

tells mod_perl to load the Apache::Compress module

before using it, as we will see later.

Using

<FilesMatch>,

it is possible to embed sections inside other sections to create

subgroups that have their own distinct behavior. Alternatively, you

could also use a <Files> section inside an

.htaccess file.

Note that you can’t put

<Files> or

<FilesMatch> sections inside a

<Location> section, but you can put them

inside a <Directory> section.

Normally, if

multiple Options

directives apply to a directory, the most specific one is taken

completely; the options are not merged.

However, if all the options on the Options

directive are preceded by either a + or

- symbol, the options are merged. Any options

preceded by + are added to the options currently

active, and any options preceded by - are removed.

For example, without any + or -

symbols:

<Directory /home/httpd/docs>

Options Indexes FollowSymLinks

</Directory>

<Directory /home/httpd/docs/shtml>

Options Includes

</Directory>

Indexes and FollowSymLinks will

be set for /home/httpd/docs/, but only

Includes will be set for the

/home/httpd/docs/shtml/ directory. However, if

the second Options directive uses the

+ and - symbols:

<Directory /home/httpd/docs>

Options Indexes FollowSymLinks

</Directory>

<Directory /home/httpd/docs/shtml>

Options +Includes -Indexes

</Directory>then the options FollowSymLinks and

Includes will be set for the

/home/httpd/docs/shtml/ directory.

MinSpareServers

,

MaxSpareServers

,

StartServers

, and

MaxClients

are

standard Apache configuration

directives that control the number of servers being launched at

server startup and kept alive during the server’s

operation. When Apache starts, it spawns

StartServers child processes. Apache makes sure

that at any given time there will be at least

MinSpareServers but no more than

MaxSpareServers idle servers. However, the

MinSpareServers rule is completely satisfied only

if the total number of live servers is no bigger than

MaxClients.

MaxRequestsPerChild lets you specify the maximum

number of requests to be served by each child. When a process has

served MaxRequestsPerChild requests, the parent

kills it and replaces it with a new one. There may also be other

reasons why a child is killed, so each child will not necessarily

serve this many requests; however, each child will not be allowed to

serve more than this number of requests. This feature is handy to

gain more control of the server, and especially to avoid child

processes growing too big (RAM-wise) under mod_perl.

These five directives are very important for getting the best performance out of your server. The process of tuning these variables is described in great detail in Chapter 11.

When you have tested that the Apache server works on your machine, it’s time to configure the mod_perl part. Although some of the configuration directives are already familiar to you, mod_perl introduces a few new ones.

It’s a good idea to keep all mod_perl-related configuration at the end of the configuration file, after the native Apache configuration directives, thus avoiding any confusion.

To ease maintenance and to simplify multiple-server installations,

the mod_perl-enabled Apache server configuration system provides

several alternative ways to keep your configuration directives in

separate places. The

Include

directive in

httpd.conf lets you include the contents of

other files, just as if the information were all contained in

httpd.conf. This is a

feature of Apache itself. For example,

placing all mod_perl-related configuration in a separate file named

conf/mod_perl.conf can be done by adding the

following directive to httpd.conf:

Include conf/mod_perl.conf

If you want to include this configuration conditionally, depending on

whether your Apache has been compiled with mod_perl, you can use the

IfModule directive :

<IfModule mod_perl.c> Include conf/mod_perl.conf </IfModule>

mod_perl adds two more directives.

<Perl>

sections allow you to execute Perl code from within any configuration

file at server startup time. Additionally, any file containing a Perl

program can be executed at server startup simply by using the

PerlRequire or PerlModule

directives, as we will show shortly.

For many reasons, a server can never allow access to its entire directory hierarchy. Although there is really no indication of this given to the web browser, every path given in a requested URI is therefore a virtual path; early in the processing of a request, the virtual path given in the request must be translated to a path relative to the filesystem root, so that Apache can determine what resource is really being requested. This path can be considered to be a physical path, although it may not physically exist.

For instance, in mod_perl systems, you may intend that the translated path does not physically exist, because your module responds when it sees a request for this non-existent path by sending a virtual document. It creates the document on the fly, specifically for that request, and the document then vanishes. Many of the documents you see on the Web (for example, most documents that change their appearance depending on what the browser asks for) do not physically exist. This is one of the most important features of the Web, and one of the great powers of mod_perl is that it allows you complete flexibility to create virtual documents.

The ScriptAlias

and Alias

directives provide a mapping of a URI to a filesystem directory. The

directive:

Alias /foo /home/httpd/foo

will map all requests starting with /foo to the files starting with /home/httpd/foo/. So when Apache receives a request to http://www.example.com/foo/test.pl, the server will map it to the file test.pl in the directory /home/httpd/foo/.

Additionally, ScriptAlias assigns all the requests

that match the specified URI (i.e., /cgi-bin) to

be executed by mod_cgi.

ScriptAlias /cgi-bin /home/httpd/cgi-bin

is actually the same as:

Alias /cgi-bin /home/httpd/cgi-bin

<Location /cgi-bin>

SetHandler cgi-script

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>where the SetHandler

directive invokes mod_cgi. You

shouldn’t use the ScriptAlias

directive unless you want the request to be processed under mod_cgi.

Therefore, when configuring mod_perl sections, use

Alias instead.

Under mod_perl, the Alias directive will be

followed by a section with at least two directives. The first is the

SetHandler/perl-script

directive, which tells Apache to

invoke mod_perl to run the script. The second directive (for example,

PerlHandler) tells mod_perl which handler (Perl

module) the script should be run under, and hence for which phase of

the request. Later in this chapter, we discuss the available

Perl*Handlers[1] for

the various request phases. A typical mod_perl configuration that

will execute the Perl scripts under the

Apache::Registry handler looks like this:

Alias /perl/ /home/httpd/perl/

<Location /perl>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Registry

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>The last directive tells Apache to execute the file as a program, rather than return it as plain text.

When you have decided which methods to use to run your scripts and where you will keep them, you can add the configuration directive(s) to httpd.conf. They will look like those below, but they will of course reflect the locations of your scripts in your filesystem and the decisions you have made about how to run the scripts:

ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ /home/httpd/cgi-bin/

Alias /perl/ /home/httpd/perl/

<Location /perl>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Registry

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>In the examples above, all requests issued for URIs starting with /cgi-bin will be served from the directory /home/httpd/cgi-bin/, and those starting with /perl will be served from the directory /home/httpd/perl/.

Sometimes you will want to map the same directory to a few different locations and execute each file according to the way it was requested. For example, in the following configuration:

# Typical for plain cgi scripts:

ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ /home/httpd/perl/

# Typical for Apache::Registry scripts:

Alias /perl/ /home/httpd/perl/

# Typical for Apache::PerlRun scripts:

Alias /cgi-perl/ /home/httpd/perl/

<Location /perl/>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Registry

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>

<Location /cgi-perl/>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::PerlRun

Options +ExecCGI

</Location>the following three URIs:

http://www.example.com/perl/test.pl http://www.example.com/cgi-bin/test.pl http://www.example.com/cgi-perl/test.pl

are all mapped to the same file,

/home/httpd/perl/test.pl. If

test.pl is invoked with the URI prefix

/perl, it will be executed under the

Apache::Registry handler. If the prefix is

/cgi-bin, it will be executed under mod_cgi, and

if the prefix is /cgi-perl, it will be executed

under the Apache::PerlRun handler.

This means that we can have all our CGI scripts located at the same place in the filesystem and call the script in any of three ways simply by changing one component of the URI (cgi-bin|perl|cgi-perl).

This technique makes it easy to migrate your scripts to mod_perl. If

your script does not seem to work while running under mod_perl, in

most cases you can easily call the script in straight mod_cgi mode or

under Apache::PerlRun without making any script

changes. Simply change the URL you use to invoke it.

Although in the configuration above we have configured all three

Aliases to point to the same directory within our

filesystem, you can of course have them point to different

directories if you prefer.

This should just be a migration strategy, though. In general, it’s a bad idea to run scripts in plain mod_cgi mode from a mod_perl-enabled server—the extra resource consumption is wasteful. It is better to run these on a plain Apache server.

The

<Location>

section assigns a number of rules that the server follows when the

request’s URI matches the location. Just as it is a

widely accepted convention to use /cgi-bin for

mod_cgi scripts, it is habitual to use /perl as

the base URI of the Perl scripts running under mod_perl.

Let’s review the following very widely used

<Location> section:

Alias /perl/ /home/httpd/perl/

PerlModule Apache::Registry

<Location /perl>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::Registry

Options +ExecCGI

Allow from all

PerlSendHeader On

</Location>This configuration causes all requests for URIs starting with

/perl to be handled by the mod_perl Apache

module with the handler from the Apache::Registry

Perl module.

Remember the Alias from the previous section? We

use the same Alias here. If you use a

<Location> that does not have the same

Alias, the server will fail to locate the script

in the filesystem. You need the Alias setting only

if the code that should be executed is located in a file.

Alias just provides the URI-to-filepath

translation rule.

Sometimes there is no script to be executed. Instead, a method in a

module is being executed, as with /perl-status,

the code for which is stored in an Apache module. In such cases, you

don’t need Alias settings for

these <Location>s.

PerlModule is equivalent to

Perl’s native use( ) function

call. We use it to load the Apache::Registry

module, later used as a handler in the

<Location> section.

Now let’s go through the directives inside the

<Location> section:

-

SetHandler perl-script The

SetHandlerdirective assigns the mod_perl Apache module to handle the content generation phase.-

PerlHandler Apache::Registry The

PerlHandlerdirective tells mod_perl to use theApache::RegistryPerl module for the actual content generation.-

Options +ExecCGI Options +ExecCGIordinarily tells Apache that it’s OK for the directory to contain CGI scripts. In this case, the flag is required byApache::Registryto confirm that you really know what you’re doing. Additionally, all scripts located in directories handled byApache::Registrymust be executable, another check against wayward non-script files getting left in the directory accidentally. If you omit this option, the script either will be rendered as plain text or will trigger a Save As dialog, depending on the client. [2]-

Allow from all The

Allowdirective is used to set access control based on the client’s domain or IP adress. Thefrom allsetting allows any client to run the script.-

PerlSendHeader On The

PerlSendHeader Online tells mod_perl to intercept anything that looks like a header line (such asContent-Type: text/html) and automatically turn it into a correctly formatted HTTP header the way mod_cgi does. This lets you write scripts without bothering to call the request object’ssend_http_header( )method, but it adds a small overhead because of the special handling.

If you use CGI.pm’s

header( ) function to generate HTTP headers, you

do not need to activate this directive, because

CGI.pm detects that it’s running

under mod_perl and calls send_http_header( ) for

you.

You will want to set PerlSendHeader Off for

non-parsed headers (nph) scripts and generate

all the HTTP headers yourself. This is also true for mod_perl

handlers that send headers with the send_http_header(

) method, because having PerlSendHeader

On as a server-wide configuration option might be a

performance hit.

-

</Location> </Location>closes the<Location>section definition.

As we

saw earlier, a module should be loaded

before its handler can be used.

PerlModule

and

PerlRequire

are the two mod_perl directives that

are used to load modules and code. They are almost equivalent to

Perl’s use( ) and

require( ) functions (respectively) and are called

from the Apache configuration file. You can pass one or more module

names as arguments to PerlModule:

PerlModule Apache::DBI CGI DBD::Mysql

Generally, modules are preloaded from the startup script, which is

usually called startup.pl. This is a file

containing Perl code that is executed through the

PerlRequire directive. For example:

PerlRequire /home/httpd/perl/lib/startup.pl

A PerlRequire filename can be absolute or relative

to the ServerRoot or to a path in

@INC.

As with any file with Perl code that gets use( )d

or require( )d, it must return a true value. To

ensure that this happens, don’t forget to add

1; at the end of startup.pl.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, Apache specifies 11 phases of the request loop. In order of processing, they are: Post-read-request, URI translation, header parsing, access control, authentication, authorization, MIME type checking, fixup, response (also known as the content handling phase), logging, and finally cleanup. These are the stages of a request where the Apache API allows a module to step in and do something. mod_perl provides dedicated configuration directives for each of these stages:

PerlPostReadRequestHandler PerlInitHandler PerlTransHandler PerlHeaderParserHandler PerlAccessHandler PerlAuthenHandler PerlAuthzHandler PerlTypeHandler PerlFixupHandler PerlHandler PerlLogHandler PerlCleanupHandler

These configuration directives usually are referred to as

Perl*Handler directives. The *

in Perl*Handler is a placeholder to be replaced by

something that identifies the phase to be handled. For example,

PerlLogHandler is the Perl handler that (fairly

obviously) handles the logging phase.

In addition, mod_perl adds a few more stages that happen outside the request loop:

-

PerlChildInitHandler Allows your modules to initialize data structures during the startup of the child process.

-

PerlChildExitHandler Allows your modules to clean up during the child process shutdown.

PerlChildInitHandlerandPerlChildExitHandlermight be used, for example, to allocate and deallocate system resources, pre-open and close database connections, etc. They do not refer to parts of the request loop.-

PerlRestartHandler Allows you to specify a routine that is called when the server is restarted. Since Apache always restarts itself immediately after it starts, this is a good phase for doing various initializations just before the child processes are spawned.

-

PerlDispatchHandler Can be used to take over the process of loading and executing handler code. Instead of processing the

Perl*Handlerdirectives directly, mod_perl will invoke the routine pointed to byPerlDispatchHandlerand pass it the Apache request object and a second argument indicating the handler that would ordinarily be invoked to process this phase. So for example, you can write aPerlDispatchHandlerhandler with a logic that will allow only specific code to be executed.

Since most mod_perl applications need to handle only the response

phase, in the default compilation, most of the

Perl*Handlers are disabled. During the

perl Makefile.PL mod_perl build stage, you must

specify whether or not you will want to handle parts of the request

loop other than the usual content generation phase. If this is the

case, you need to specify which phases, or build mod_perl with the

option EVERYTHING=1, which enables them all. All

the build options are covered in detail in Chapter 3.

Note that it is mod_perl that recognizes these directives, not Apache. They are mod_perl directives, and an ordinary Apache server will not recognize them. If you get error messages about these directives being “perhaps mis-spelled,” it is a sure sign that the appropriate part of mod_perl (or the entire mod_perl module!) is missing from your server.

All <Location>,

<Directory>, and

<Files> sections contain a physical path

specification. Like PerlChildInitHandler and

PerlChildExitHandler, the directives

PerlPostReadRequestHandler and

PerlTransHandler cannot be used in these sections,

nor in .htaccess files, because the path

translation isn’t completed and a physical path

isn’t known until the end of the translation

(PerlTransHandler) phase.

PerlInitHandler is more of an alias; its behavior

changes depending on where it is used. In any case, it is the first

handler to be invoked when serving a request. If found outside any

<Location>,

<Directory>, or

<Files> section, it is an alias for

PerlPostReadRequestHandler. When inside any such

section, it is an alias for

PerlHeaderParserHandler.

Starting with the header parsing phase, the

requested URI has been mapped to a physical server pathname, and thus

PerlHeaderParserHandler can be used to match a

<Location>,

<Directory>, or

<Files> configuration section, or to process

an .htaccess file if such a file exists in the

specified directory in the translated path.

PerlDispatchHandler,

PerlCleanupHandler, and

PerlRestartHandler do not correspond to parts of

the Apache API, but allow you to fine-tune the mod_perl API. They are

specified outside configuration sections.

The Apache documentation and the book Writing Apache Modules with Perl and C (O’Reilly) provide in-depth information on the request phases.

By default, the

mod_perl API expects a subroutine named

handler( ) to handle the request in the registered

Perl*Handler module. Thus, if your module

implements this subroutine, you can register the handler with

mod_perl by just specifying the module name. For example, to set the

PerlHandler to

Apache::Foo::handler, the following setting would

be sufficient:

PerlHandler Apache::Foo

mod_perl will load the specified module for you when it is first used. Please note that this approach will not preload the module at startup. To make sure it gets preloaded, you have three options:

You can explicitly preload it with the

PerlModuledirective:PerlModule Apache::Foo

You can preload it in the startup file:

use Apache::Foo ( );

You can use a nice shortcut provided by the

Perl*Handlersyntax:PerlHandler +Apache::Foo

Note the leading

+character. This directive is equivalent to:PerlModule Apache::Foo <Location ..> ... PerlHandler Apache::Foo </Location>

If you decide to give the handler routine a name other than

handler( ) (for example, my_handler(

)), you must preload the module and explicitly give the

name of the handler subroutine:

PerlModule Apache::Foo

<Location ..>

...

PerlHandler Apache::Foo::my_handler

</Location>This configuration will preload the module at server startup.

If a module needs to know which handler is currently being run, it

can find out with the current_callback( ) method.

This method is most useful to PerlDispatchHandlers

that take action for certain phases only.

if ($r->current_callback eq "PerlLogHandler") {

$r->warn("Logging request");

}Imagine a complex server setup in which many

different Perl and non-Perl handlers participate in the request

processing, and one or more of these handlers misbehaves. A simple

example is one where one of the handlers alters the request record,

which breaks the functionality of other handlers. Or maybe a handler

invoked first for any given phase of the process returns an

unexpected OK status, thus preventing other

handlers from doing their job. You can’t just add

debug statements to trace the offender—there are too many

handlers involved.

The simplest solution is to get a trace of all registered handlers for each phase, stating whether they were invoked and what their return statuses were. Once such a trace is available, it’s much easier to look only at the players that actually participated, thus narrowing the search path down a potentially misbehaving module.

The

Apache::ShowRequest

module shows the phases the request goes through, displaying module

participation and response codes for each phase. The content response

phase is not run, but possible modules are listed as defined. To

configure it, just add this snippet to

httpd.conf:

<Location /showrequest>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler +Apache::ShowRequest

</Location>To see what happens when you access some URI, add the URI to

/showrequest.

Apache::ShowRequest uses

PATH_INFO to obtain the URI that should be

executed. So, to run /index.html with

Apache::ShowRequest, issue a request for

/showrequest/index.html. For

/perl/test.pl, issue a request for

/showrequest/perl/test.pl.

This module produces rather lengthy output, so we will show only one section from the report generated while requesting /showrequest/index.html:

Running request for /index.html Request phase: post_read_request [snip] Request phase: translate_handler mod_perl ....................DECLINED mod_setenvif ................undef mod_auth ....................undef mod_access ..................undef mod_alias ...................DECLINED mod_userdir .................DECLINED mod_actions .................undef mod_imap ....................undef mod_asis ....................undef mod_cgi .....................undef mod_dir .....................undef mod_autoindex ...............undef mod_include .................undef mod_info ....................undef mod_status ..................undef mod_negotiation .............undef mod_mime ....................undef mod_log_config ..............undef mod_env .....................undef http_core ...................OK Request phase: header_parser [snip] Request phase: access_checker [snip] Request phase: check_user_id [snip] Request phase: auth_checker [snip] Request phase: type_checker [snip] Request phase: fixer_upper [snip] Request phase: response handler (type: text/html) mod_actions .................defined mod_include .................defined http_core ...................defined Request phase: logger [snip]

For each stage, we get a report of what modules could participate in the processing and whether they took any action. As you can see, the content response phase is not run, but possible modules are listed as defined. If we run a mod_perl script, the response phase looks like:

Request phase: response handler (type: perl-script) mod_perl ....................defined

With the

mod_perl stacked

handlers mechanism, it is possible for more than one

Perl*Handler to be defined and executed during any

stage of a request.

Perl*Handler directives can define any number of

subroutines. For example:

PerlTransHandler Foo::foo Bar::bar

Foo::foo( ) will be executed first and

Bar::bar( ) second. As always, if the

subroutine’s name is handler( ),

you can omit it.

With the Apache->push_handlers( ) method,

callbacks (handlers) can be added to a stack at

runtime by mod_perl modules.

Apache->push_handlers( ) takes the callback

handler name as its first argument and a subroutine name or reference

as its second. For example, let’s add two handlers

called my_logger1( ) and my_logger2(

) to be executed during the logging phase:

use Apache::Constants qw(:common);

sub my_logger1 {

#some code here

return OK;

}

sub my_logger2 {

#some other code here

return OK;

}

Apache->push_handlers("PerlLogHandler", \&my_logger1);

Apache->push_handlers("PerlLogHandler", \&my_logger2);You can also pass a reference to an anonymous subroutine. For example:

use Apache::Constants qw(:common);

Apache->push_handlers("PerlLogHandler", sub {

print STDERR "_ _ANON_ _ called\n";

return OK;

});After each request, this stack is erased.

All handlers will be called in turn, unless a handler returns a

status other than OK or

DECLINED.

To enable this feature, build mod_perl with:

panic% perl Makefile.PL PERL_STACKED_HANDLERS=1 [ ... ]

or:

panic% perl Makefile.PL EVERYTHING=1 [ ... ]

To test whether the version of mod_perl you’re

running can stack handlers, use the

Apache->can_stack_handlers

method. This method will return a true

value if mod_perl was configured with

PERL_STACKED_HANDLERS=1, and a false value

otherwise.

Let’s look at a few real-world examples where this method is used:

The widely used

CGI.pmmodule maintains a global object for its plain function interface. Since the object is global, under mod_perl it does not go out of scope when the request is completed, and theDESTROYmethod is never called. Therefore,CGI->newarranges to call the following code if it detects that the module is used in the mod_perl environment:Apache->push_handlers("PerlCleanupHandler", \&CGI::_reset_globals);This function is called during the final stage of a request, resetting

CGI.pm’s globals before the next request arrives.Apache::DCELoginestablishes a DCE login context that must exist for the lifetime of a request, so theDCE::Loginobject is stored in a global variable. Without stacked handlers, users must set the following directive in the configuration file to destroy the context:PerlCleanupHandler Apache::DCELogin::purge

This is ugly. With stacked handlers,

Apache::DCELogin::handlercan call from within the code:Apache->push_handlers("PerlCleanupHandler", \&purge);Apache::DBI, the persistent database connection module, can pre-open the connection when the child process starts via itsconnect_on_init( )function. This function usespush_handlers( )to add aPerlChildInitHandler:Apache->push_handlers(PerlChildInitHandler => \&childinit);

Now when the new process gets the first request, it already has the database connection open.

Apache::DBIalso usespush_handlers( )to havePerlCleanupHandlerhandle rollbacks if itsAutoCommitattribute is turned off.PerlTransHandlers(e.g.,Apache::MsqlProxy) may decide, based on the URI or some arbitrary condition, whether or not to handle a request. Without stacked handlers, users must configure it themselves.PerlTransHandler Apache::MsqlProxy::translate PerlHandler Apache::MsqlProxy

PerlHandleris never actually invoked unlesstranslate( )sees that the request is a proxy request ($r->proxyreq). If it is a proxy request,translate( )sets$r->handler("perl-script"), and only then willPerlHandlerhandle the request. Now users do not have to specifyPerlHandler Apache::MsqlProxy, because thetranslate( )function can set it withpush_handlers( ).

Now let’s write our own example using stacked handlers. Imagine that you want to piece together a document that includes footers, headers, etc. without using SSI. The following example shows how to implement it. First we prepare the code as shown in Example 4-1.

Example 4-1. Book/Compose.pm

package Book::Compose;

use Apache::Constants qw(OK);

sub header {

my $r = shift;

$r->send_http_header("text/plain");

$r->print("header text\n");

return OK;

}

sub body {

shift->print("body text\n");

return OK;

}

sub footer {

shift->print("footer text\n");

return OK;

}

1;The code defines the package Book::Compose,

imports the OK constant, and defines three

subroutines: header( ) to send the header,

body( ) to create and send the actual content, and

finally footer( ) to add a standard footer to the

page. At the end of each handler we return OK, so

the next handler, if any, will be executed.

To enable the construction of the page, we now supply the following configuration:

PerlModule Book::Compose

<Location /compose>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Book::Compose::header Book::Compose::body Book::Compose::footer

</Location>We preload the Book::Compose module and construct

the PerlHandler directive by listing the handlers

in the order in which they should be invoked.[3]

Finally, let’s look at the technique that allows

parsing the output of another PerlHandler. For

example, suppose your module generates HTML responses, but you want

the same content to be delivered in plain text at a different

location. This is a little trickier, but consider the following:

<Location /perl>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Book::HTMLContentGenerator

</Location>

<Location /text>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Book::HTML2TextConvertor Book::HTMLContentGenerator

</Location>Notice that Book::HTML2TextConvertor is listed

first. While its handler( ) will be called first,

the actual code that does the conversion will run last, as we will

explain in a moment. Now let’s look at the sample

code in Example 4-2.

Example 4-2. Book/HTML2TextConvertor.pm

package Book::HTML2TextConvertor;

sub handler {

my $r = shift;

untie *STDOUT;

tie *STDOUT => _ _PACKAGE_ _, $r;

}

sub TIEHANDLE {

my($class, $r) = @_;

bless { r => $r}, $class;

}

sub PRINT {

my $self = shift;

for (@_) {

# copy it so no 'read-only value modification' will happen

my $line = $_;

$line =~ s/<[^>]*>//g; # strip the html <tags>

$self->{r}->print($line);

}

}

1;It untie( )s STDOUT and

re-tie( )s it to its own package, so that content

printed to STDOUT by the previous content

generator in the pipe goes through this module. In the

PRINT( ) method, we attempt to strip the HTML

tags. Of course, this is only an example; correct HTML stripping

actually requires more than one line of code and a quite complex

regular expression, but you get the

idea.

panic% perl Makefile.PL PERL_METHOD_HANDLERS=1 [ ... ]

or:

panic% perl Makefile.PL EVERYTHING=1 [ ... ]

it’s possible to write method handlers in addition

to function handlers. This is useful when you want to write code that

takes advantage of inheritance. To make the handler act as a method

under mod_perl, use the $$ function prototype in

the handler definition. When mod_perl sees that the handler function

is prototyped with $$, it’ll pass

two arguments to it: the calling object or a class, depending on how

it was called, and the Apache request object. So you can write the

handler as:

sub handler ($$) {

my($self, $r) = @_;

# ...

}The configuration

is almost as usual. Just use the

class name if the default method name handler( )

is used:

PerlHandler Book::SubClass

However, if you choose to use a different method name, the object-oriented notation should be used:

PerlHandler Book::SubClass->my_handler

The my_handler( ) method will then be called as a

class (static) method.

Also, you can use objects created at startup to call methods. For example:

<Perl>

use Book::SubClass;

$Book::Global::object = Book::SubClass->new( );

</Perl>

...

PerlHandler $Book::Global::object->my_handlerIn this example, the my_handler( ) method will be

called as an instance method on the global object

$Book::Global.

To reload

PerlRequire,

PerlModule, and other use( )d

modules, and to flush the Apache::Registry cache

on server restart, add this directive to

httpd.conf:

PerlFreshRestart On

You should be careful using this setting. It used to cause trouble in older versions of mod_perl, and some people still report problems using it. If you are not sure if it’s working properly, a full stop and restart of the server will suffice.

Starting with mod_perl Version 1.22,

PerlFreshRestart is ignored when mod_perl is

compiled as a DSO. But it almost doesn’t matter, as

mod_perl as a DSO will do a full tear-down (calling

perl_destruct( )).[4]

In addition to

Apache’s

SetEnv and PassEnv directives,

respectively setting and passing shell environment variables,

mod_perl provides its own directives:

PerlSetEnv

and

PerlPassEnv

.

If you want to globally set an environment variable for the server,

you can use the PerlSetEnv directive. For example,

to configure the mod_perl tracing mechanism (as discussed in Chapter 21), add this to httpd.conf:

PerlSetEnv MOD_PERL_TRACE all

This will enable full mod_perl tracing.

Normally, PATH is the only shell environment

variable available under mod_perl. If you need to rely on other

environment variables, you can have mod_perl make those available for

your code with PerlPassEnv.

For example, to forward the environment variable

HOME (which is usually set to the home of the user

who has invoked the server in httpd.conf), add:

PerlPassEnv HOME

Once you set the environment variable, it can be accessed via the

%ENV hash in Perl (e.g.,

$ENV{HOME}).

PerlSetEnv and PerlPassEnv work

just like the Apache equivalents, except that they take effect in the

first phase of the Apache request cycle. The standard Apache

directives SetEnv and PassEnv

don’t affect the environment until the fixup phase,

which happens much later, just before content generation. This works

for CGI scripts, which aren’t run before then, but

if you need to set some environment variables and access them in a

handler invoked before the response stage, you should use the

mod_perl directives. For example, handlers that want to use an Oracle

relational database during the authentication phase might need to set

the following environment variable (among others) in

httpd.conf:

PerlSetEnv ORACLE_HOME /share/lib/oracle/

Note that PerlSetEnv will override the environment

variables that were available earlier. For example, we have mentioned

that PATH is always supplied by Apache itself. But

if you explicitly set:

PerlSetEnv PATH /tmp

this setting will be used instead of the one set in the shell program.

As with other configuration scoping rules, if you place

PerlSetEnv or PerlPassEnv in

the scope of the configuration file, it will apply everywhere (unless

overridden). If placed into a <Location>

section, or another section in the same group, these directives will

influence only the handlers in that section.

PerlSetVar

is another directive introduced by

mod_perl. It is very similar to PerlSetEnv, but

the key/value pairs are stored in an Apache::Table

object and retrieved using the dir_config( )

method.

There are two ways to use PerlSetVar. The first is

the usual way, as a configuration directive. For example:

PerlSetVar foo bar

The other way is via Perl code in <Perl>

sections:

<Perl>

push @{ $Location{"/"}->{PerlSetVar} }, [ foo => 'bar' ];

</Perl>Now we can retrieve the value of foo using the

dir_config( ) method:

$foo = $r->dir_config('foo');Note that you cannot use the following code in

<Perl> sections, which we discuss later in

this chapter:

<Perl>

my %foo = (a => 0, b => 1);

push @{ $Location{"/"}->{PerlSetVar} }, [ foo => \%foo ];

</Perl>All values are passed to Apache::Table as strings,

so you will get a stringified reference to a hash as a value (such as

"HASH(0x87a5108)“). This cannot be turned back

into the original hash upon retrieval.

However, you can use the

PerlAddVar

directive to push more values into

the variable, emulating arrays. For example:

PerlSetVar foo bar PerlAddVar foo bar1 PerlAddVar foo bar2

or the equivalent:

PerlAddVar foo bar PerlAddVar foo bar1 PerlAddVar foo bar2

To retrieve the values, use the $r->dir_config->get(

) method:

my @foo = $r->dir_config->get('foo');Obviously, you can always turn an array into a hash with Perl, so you can use this directive to pass hashes as well. Consider this example:

PerlAddVar foo key1 PerlAddVar foo value1 PerlAddVar foo key2 PerlAddVar foo value2

You can then retrieve the hash in this way:

my %foo = $r->dir_config->get('foo');Make sure that you use an even number of elements if you store the retrieved values in a hash.

Passing a list or a hash via the PerlAddVar

directive in a <Perl> section should be

coded in this way:

<Perl>

my %foo = (a => 0, b => 1);

for (%foo) {

push @{ $Location{"/"}->{PerlAddVar} }, [ foo => $_ ];

}

</Perl>Now you get back the hash as before:

my %foo = $r->dir_config->get('foo');This might not seem very practical; if you have more complex needs, think about having dedicated configuration files.

Customized configuration directives can also be created for the specific needs of a Perl module. To learn how to create these, please refer to Chapter 8 of Writing Apache Modules with Perl and C (O’Reilly), which covers this topic in great detail.

Certain Perl modules used in CGI code (such as

CGI.pm) rely on a number of environment variables

that are normally set by mod_cgi. For example, many modules depend on

QUERY_STRING, SCRIPT_FILENAME,

and REQUEST_URI. When the

PerlSetupEnv

directive is turned on,

mod_perl provides these environment variables in the same fashion

that mod_cgi does. This directive is On by

default, which means that all the environment variables you are

accustomed to being available under mod_cgi are also available under

mod_perl.

The process of setting these environment variables adds overhead for each request, whether the variables are needed or not. If you don’t use modules that rely on this behavior, you can turn it off in the general configuration and then turn it on in sections that need it (such as legacy CGI scripts):

PerlSetupEnv Off

<Location /perl-run>

SetHandler perl-script

PerlHandler Apache::PerlRun

Options +ExecCGI

PerlSetupEnv On

</Location>You can use mod_perl methods to access the information provided by

these environment variables (e.g.,

$r->path_info instead of

$ENV{PATH_INFO}). For more details, see the

explanation in Chapter 11.

PerlWarn

and

PerlTaintCheck

have two possible values,

On and Off.

PerlWarn turns warnings on and off globally to the

whole server, and PerlTaintCheck controls whether

the server is running with taint checking or not. These two variables

are also explained

in Chapter 6.

At server startup, before child processes are spawned, you can do much more than just preload modules. You might want to register code that will initialize a database connection for each child when it is forked, tie read-only DBM files, fill in shared caches, etc.

The startup.pl file is an ideal place to put

code that should be executed when the server starts. Once you have

prepared the code, load it in httpd.conf before

other mod_perl configuration directives with the

PerlRequire directive:

PerlRequire /home/httpd/perl/lib/startup.pl

Be careful with the startup file. Everything run at server

initialization is run with root privileges if

you start the server as root (which you have to

do unless you choose to run the server on an unprivileged port,

numbered 1024 or higher). This means that anyone who has write access

to a script or module that is loaded by

PerlModule, PerlRequire, or

<Perl> sections effectively has

root access to the system.

Let’s look at a real-world startup file. The elements of the file are shown here, followed by their descriptions.

use strict;

This pragma is worth using in every script longer than half a dozen lines. It will save a lot of time and debugging later.

use lib qw(/home/httpd/lib /home/httpd/extra-lib);

This permanently adds extra directories to @INC,

something that’s possible only during server

startup. At the end of each request’s processing,

mod_perl resets @INC to the value it had after the

server startup. Alternatively, you can use the

PERL5LIB environment variable to add extra

directories to @INC.

$ENV{MOD_PERL} or die "not running under mod_perl!";This is a sanity check. If mod_perl wasn’t properly built, the server startup is aborted.

use Apache::Registry ( ); use LWP::UserAgent ( ); use Apache::DBI ( ); use DBI ( );

Preload the

modules that get used by Perl code serving

requests. Unless you need the symbols (variables and subroutines)

exported by preloaded modules to accomplish something within the

startup file, don’t import

them—it’s just a waste of startup time and

memory. Instead, use the empty import list ( ) to

tell the import( )

function not to import anything.

use Carp ( );

$SIG{_ _WARN_ _} = \&Carp::cluck;This is a useful snippet to enable extended warnings logged in the error_log file. In addition to basic warnings, a trace of calls is added. This makes tracking potential problems a much easier task, since you know who called what.

The only drawback of this method is that it globally overrides the

default warning handler behavior—thus, in some places it might

be desirable to change the settings locally (for example, with

local $^W=0, or no warnings

under Perl 5.6.0 and higher). Usually warnings are turned off on

production machines to prevent unnecessary clogging of the

error_log file if your code is not very clean.

Hence, this method is mostly useful in a development environment.

use CGI ( );

CGI->compile(':all');Some modules, such as CGI.pm, create their

subroutines at runtime via AUTOLOAD to improve

their loading time. This helps when the module includes many

subroutines but only a few are actually used. (Also refer to the

AutoSplit manpage.) Since the module is loaded

only once with mod_perl, it might be a good idea to precompile all or

some of its methods at server startup. This avoids the overhead of

compilation at runtime. It also helps share more compiled code

between child processes.

CGI.pm’s compile(

)

method performs this task. Note that

compile( ) is specific to

CGI.pm; other

modules that implement this feature may use another name for the

compilation method.

As with all modules we preload in the startup file, we don’t import symbols from them because they will be lost when they go out of the file’s scope.

The following code snippet makes sure that when the child process is spawned, a connection to the database is opened automatically, avoiding this performance hit on the first request:

Apache::DBI->connect_on_init

("DBI:mysql:database=test;host=localhost",

"user", "password", {

PrintError => 1, # warn( ) on errors

RaiseError => 0, # don't die on error

AutoCommit => 1, # commit executes immediately

}

);We discuss this method in detail in Chapter 20.

The file ends with 1; so it can be successfully

loaded by Perl.

The entire startup.pl file is shown in Example 4-3.

Example 4-3. startup.pl

use strict;

use lib qw(/home/httpd/lib /home/httpd/extra-lib);

$ENV{MOD_PERL} or die "not running under mod_perl!";

use Apache::Registry ( );

use LWP::UserAgent ( );

use Apache::DBI ( );

use DBI ( );

use Carp ( );

$SIG{_ _WARN_ _} = \&Carp::cluck;

use CGI ( );

CGI->compile(':all');

Apache::DBI->connect_on_init

("DBI:mysql:database=test;host=localhost",

"user", "password", {

PrintError => 1, # warn( ) on errors

RaiseError => 0, # don't die on error

AutoCommit => 1, # commit executes immediately

}

);

1;If the startup file doesn’t include any modules that require the mod_perl runtime environment during their loading, you can validate its syntax with:

panic% perl -cw /home/httpd/perl/lib/startup.pl

The -c switch tells Perl to validate only the file’s syntax, and the -w switch enables warnings.

Apache::DBI is an example of a module that cannot

be loaded outside of the mod_perl environment. If you try to load it,

you will get the following error message:

panic% perl -MApache::DBI -c -e 1 Can't locate object method "module" via package "Apache" (perhaps you forgot to load "Apache"?) at /usr/lib/perl5/site_perl/5.6.1/Apache/DBI.pm line 202. Compilation failed in require. BEGIN failed--compilation aborted.

However, Apache::DBI will work perfectly once

loaded from within mod_perl.

Every module loaded at server startup will be shared among the server children, saving a lot of RAM on your machine. Usually, we put most of the code we develop into modules and preload them.

You can even preload CGI scripts with

Apache::RegistryLoader, as explained in Chapter 10.

Some people

wonder why they need to duplicate use Modulename

in the startup file and in the script itself. The confusion arises

due to misunderstanding use( ).

Let’s take the POSIX module as an

example. When you write:

use POSIX qw(setsid);

use( ) internally performs two operations:

BEGIN {

require POSIX;

POSIX->import(qw(setsid));

}The first operation loads and compiles the module. The second calls

the module’s import( ) method and

specifies to import the symbol setsid into the

caller’s namespace. The BEGIN

block makes sure that the code is executed as soon as possible,

before the rest of the code is even parsed. POSIX,

like many other modules, specifies a default export list. This is an

especially extensive list, so when you call:

use POSIX;

about 500 KB worth of symbols gets imported.

Usually, we don’t need POSIX or

its symbols in the startup file; all we want is to preload it.

Therefore, we use an empty list as an argument for use(

):

use POSIX ( );

so the POSIX::import( ) method

won’t be even called.

When we want to use the POSIX module in the code,

we use( ) it again, but this time no loading

overhead occurs because the module has been loaded already. If we

want to import something from the module, we supply the list of

symbols to load:

use POSIX qw(:flock_h);

This example loads constants used with the flock(

) function.

Technically, you aren’t required to supply the

use( ) statement in your handler code if the

module has already been loaded during server startup or elsewhere.

When writing your code, however, don’t assume that

the module code has been preloaded. Someday in the future, you or

someone else will revisit this code and will not understand how it is

possible to use a module’s methods without first

loading the module itself.

Please refer to the Exporter and

perlmod manpages, and to the section on

use( ) in the perlfunc

manpage for more information about import( ).

Remember that you can always use require( ) to

preload the files at server startup if you don’t add

( ), because:

require Data::Dumper;

is the same as:

use Data::Dumper ( );

except that it’s not executed at compile-time.

With <Perl> ...

</Perl> sections,

you

can

configure your server entirely in Perl. It’s

probably not worth it if you have simple configuration files, but if

you run many virtual hosts or have complicated setups for any other

reason, <Perl> sections become very handy.

With <Perl> sections you can easily create

the configuration on the fly, thus reducing duplication and easing

maintenance.[5]

To enable <Perl> sections, build mod_perl

with:

panic% perl Makefile.PL PERL_SECTIONS=1 [ ... ]

or with EVERYTHING=1.

<Perl> sections

can contain

any and as much Perl code as you wish.

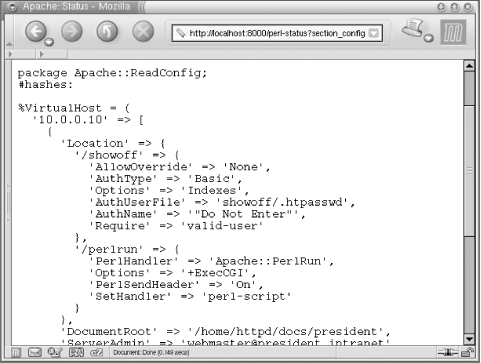

<Perl> sections are compiled into a special

package called Apache::ReadConfig. mod_perl looks

through the symbol table for Apache::ReadConfig

for Perl variables and structures to grind through the Apache core

configuration gears. Most of the configuration directives can be

represented as scalars ($scalar) or arrays

(@array). A few directives become hashes.

How do you know which Perl global variables to use? Just take the

Apache directive name and prepend either $,

@, or % (as shown in the

following examples), depending on what the directive accepts. If you

misspell the directive, it is silently ignored, so

it’s a good idea to check your settings.

Since Apache directives are case-insensitive, their Perl equivalents are case-insensitive as well. The following statements are equivalent:

$User = 'stas'; $user = 'stas'; # the same

Let’s look at all possible cases we might encounter while configuring Apache in Perl:

Directives that accept zero or one argument are represented as scalars. For example,

CacheNegotiatedDocsis a directive with no arguments. In Perl, we just assign it an empty string:<Perl> $CacheNegotiatedDocs = ''; </Perl>Directives that accept a single value are simple to handle. For example, to configure Apache so that child processes run as user httpd and group httpd, use:

User = httpd Group = httpd

What if we don’t want user and group definitions to be hardcoded? Instead, what if we want to define them on the fly using the user and group with which the server is started? This is easily done with

<Perl>sections:<Perl> $User = getpwuid($>) || $>; $Group = getgrgid($)) || $); </Perl>We use the power of the Perl API to retrieve the data on the fly.

$Useris set to the name of the effective user ID with which the server was started or, if the name is not defined, the numeric user ID. Similarly,$Groupis set to either the symbolic value of the effective group ID or the numeric group ID.Notice that we’ve just taken the Apache directives and prepended a

$, as they represent scalars.Directives that accept more than one argument are represented as arrays or as a space-delimited string. For example, this directive:

PerlModule Mail::Send Devel::Peek

becomes:

<Perl> @PerlModule = qw(Mail::Send Devel::Peek); </Perl>@PerlModuleis an array variable, and we assign it a list of modules. Alternatively, we can use the scalar notation and pass all the arguments as a space-delimited string:<Perl> $PerlModule = "Mail::Send Devel::Peek"; </Perl>Directives that can be repeated more than once with different values are represented as arrays of arrays. For example, this configuration:

AddEncoding x-compress Z AddEncoding x-gzip gz tgz

becomes:

<Perl> @AddEncoding = ( ['x-compress' => qw(Z)], ['x-gzip' => qw(gz tgz)], ); </Perl>Directives that implement a container block, with beginning and ending delimiters such as

<Location>...</Location>, are represented as Perl hashes. In these hashes, the keys are the arguments of the opening directive, and the values are the contents of the block. For example:Alias /private /home/httpd/docs/private <Location /private> DirectoryIndex index.html index.htm AuthType Basic AuthName "Private Area" AuthUserFile /home/httpd/docs/private/.htpasswd Require valid-user </Location>These settings tell Apache that URIs starting with /private are mapped to the physical directory /home/httpd/docs/private/ and will be processed according to the following rules:

The users are to be authenticated using basic authentication.

PrivateArea will be used as the title of the pop-up box displaying the login and password entry form.

Only valid users listed in the password file /home/httpd/docs/private/.htpasswd and who provide a valid password may access the resources under /private/.

If the filename is not provided, Apache will attempt to respond with the index.html or index.htm directory index file, if found.

Now let’s see the equivalent

<Perl>section:<Perl> push @Alias, qw(/private /home/httpd/docs/private); $Location{"/private"} = { DirectoryIndex => [qw(index.html index.htm)], AuthType => 'Basic', AuthName => '"Private Area"', AuthUserFile => '/home/httpd/docs/private/.htpasswd', Require => 'valid-user', }; </Perl>First, we convert the

Aliasdirective into an array@Alias. Instead of assigning, however, we push the values at the end. We do this because it’s possible that we have assigned values earlier, and we don’t want to overwrite them. Alternatively, you may want to push references to lists, like this:push @Alias, [qw(/private /home/httpd/docs/private)];

Second, we convert the

Locationblock, using /private as a key to the hash%Locationand the rest of the block as its value. When the structures are nested, the normal Perl rules apply—that is, arrays and hashes turn into references. Therefore,DirectoryIndexpoints to an array reference. As shown earlier, we can always replace this array with a space-delimited string:$Location{"/private"} = { DirectoryIndex => 'index.html index.htm', ... };Also notice how we specify the value of the

AuthNameattribute:AuthName => '"Private Area"',

The value is quoted twice because Apache expects a single value for this argument, and if we write:

AuthName => 'Private Area',

<Perl>will pass two values to Apache, “Private” and “Area”, and Apache will refuse to start, with the following complaint:[Thu May 16 17:01:20 2002] [error] <Perl>: AuthName takes one argument, The authentication realm (e.g. "Members Only")

If a block section accepts two or more identical keys (as the

<VirtualHost>...</VirtualHost>section does), the same rules as in the previous case apply, but a reference to an array of hashes is used instead.In one company, we had to run an Intranet machine behind a NAT/firewall (using the 10.0.0.10 IP address). We decided up front to have two virtual hosts to make both the management and the programmers happy. We had the following simplistic setup:

NameVirtualHost 10.0.0.10 <VirtualHost 10.0.0.10> ServerName tech.intranet DocumentRoot /home/httpd/docs/tech ServerAdmin webmaster@tech.intranet </VirtualHost> <VirtualHost 10.0.0.10> ServerName suit.intranet DocumentRoot /home/httpd/docs/suit ServerAdmin webmaster@suit.intranet </VirtualHost>In Perl, we wrote it as follows:

<Perl> $NameVirtualHost => '10.0.0.10'; my $doc_root = "/home/httpd/docs"; $VirtualHost{'10.0.0.10'} = [ { ServerName => 'tech.intranet', DocumentRoot => "$doc_root/tech", ServerAdmin => 'webmaster@tech.intranet', }, { ServerName => 'suit.intranet', DocumentRoot => "$doc_root/suit", ServerAdmin => 'webmaster@suit.intranet', }, ]; </Perl>Because normal Perl rules apply, more entries can be added as needed using

push( ).[6] Let’s say we want to create a special virtual host for the company’s president to show off to his golf partners, but his fancy vision doesn’t really fit the purpose of the Intranet site. We just let him handle his own site:push @{ $VirtualHost{'10.0.0.10'} }, { ServerName => 'president.intranet', DocumentRoot => "$doc_root/president", ServerAdmin => 'webmaster@president.intranet', };Nested block directives naturally become Perl nested data structures. Let’s extend an example from the previous section:

<Perl> my $doc_root = "/home/httpd/docs"; push @{ $VirtualHost{'10.0.0.10'} }, { ServerName => 'president.intranet', DocumentRoot => "$doc_root/president", ServerAdmin => 'webmaster@president.intranet', Location => { "/private" => { Options => 'Indexes', AllowOverride => 'None', AuthType => 'Basic', AuthName => '"Do Not Enter"', AuthUserFile => 'private/.htpasswd', Require => 'valid-user', }, "/perlrun" => { SetHandler => 'perl-script', PerlHandler => 'Apache::PerlRun', PerlSendHeader => 'On', Options => '+ExecCGI', }, }, }; </Perl>We have added two

Locationblocks. The first, /private, is for the juicy stuff and accessible only to users listed in the president’s password file. The second, /perlrun, is for running dirty Perl CGI scripts, to be handled by theApache::PerlRunhandler.<Perl>sections don’t provide equivalents for<IfModule>and<IfDefine>containers. Instead, you can use themodule( )anddefine( )methods from theApachepackage. For example:<IfModule mod_ssl.c> Include ssl.conf </IfModule>can be written as:

if (Apache->module("mod_ssl.c")) { push @Include, "ssl.conf"; }And this configuration example:

<IfDefine SSL> Include ssl.conf </IfDefine>can be written as: