Chapter 1. Cocoa Development Tools

Developing applications using Cocoa and Cocoa Touch involves using a set of tools developed by Apple. In this chapter, you’ll learn about these tools, where to get them, how to use them, how they work together, and what they can do.

These development tools have a long and storied history. Originally a set of standalone application tools for the NeXTSTEP OS, they were eventually adopted by Apple for use as the official OS X tools. Later, Apple largely consolidated them into one application, known as Xcode, though some of the applications (such as Instruments and the iOS Simulator) remain somewhat separate, owing to their relatively peripheral role in the development process.

In addition to the development applications, Apple offers memberships in its Developer Programs (formerly Apple Developer Connection), which provide resources and support for developers. The programs allow access to online developer forums and specialized technical support for those interested in talking to the framework engineers.

Now, with the introduction of Apple’s curated application storefronts for OS X and iOS, these developer programs have become the official way for developers to provide their credentials when submitting applications to the Mac App Store or iTunes App Store—in essence, they are your ticket to selling apps through Apple. In this chapter, you’ll learn how to sign up for these programs, as well as how to use Xcode, the development tool used to build apps for OS X and iOS.

The Mac and iOS Developer Programs

Apple runs two developer programs, one for each of the two platforms you can write apps on: iOS and OS X.

You need to have a paid membership to the iOS Developer Program if you want to run code on your iOS devices, because signing up is the only way to obtain the necessary code-signing certificates. (At the time of writing, membership in this program costs $99 USD per year.) It isn’t as necessary to be a member of the Mac Developer Program if you don’t intend to submit apps to the Mac App Store (you may, for example, prefer to sell your apps yourself). However, the Mac Developer Program includes useful things like early access to the next version of the OS, so it’s worth your while if you’re serious about making apps. Downloading Xcode is free, even if you aren’t a member of either developer program.

Both programs provide the following, among a host of other smaller features:

- Access to the Apple Developer Forums, which are frequented by Apple engineers and designed to allow you to ask questions of your fellow developers and the people who wrote the OS.

- Access to beta versions of the OS before they are released to the public, which enables you to test your applications on the next version of OS X and iOS and make necessary changes ahead of time. You also receive beta versions of the development tools.

- A digital signing certificate (one each for OS X and iOS) used to identify you to the App Stores. Without this, you cannot submit apps to the App Store, making the programs mandatory for anyone who wants to release software either for free or for sale via the App Store.

As a developer, you can register for one or both of the developer programs. They don’t depend on each other.

Finally, registering for a developer program isn’t necessary to view the documentation or to download the current version of the developer tools, so you can play around with writing apps without opening your wallet.

Registering for a Developer Program

To register for one of the developer programs, you’ll first need an Apple ID. It’s quite likely that you already have one, as the majority of Apple’s online services require one to identify you. If you’ve ever used iCloud, the iTunes store (for music or for apps), MobileMe, or Apple’s support and repair service, you already have an ID. You might even have more than one (one of the authors of this book has four). If you don’t yet have an ID, you’ll create one as part of the registration process. When you register for a program, it gets added to your Apple ID.

To get started, visit the Apple site for the program you want to join.

- For the Mac program, go to http://developer.apple.com/programs/mac/.

- For the iOS program, go to http://developer.apple.com/programs/ios/.

Simply click through the steps to enroll.

You can choose to register as an individual or as a company. If you register as an individual, your apps will be sold under your name. If you register as a company, your apps will be sold under your company’s legal name. Choose carefully, as it’s very difficult to convince Apple to change your program’s type.

If you’re registering as an individual, you’ll just need your credit card. If you’re registering as a company, you’ll need your credit card as well as documentation that proves you have authority to bind your company to Apple’s terms and conditions.

Note

For information on code signing, and using Xcode to test and run your apps on your own physical devices, see Apple’s App Distribution Guide.

Apple usually takes about 24 hours to activate an account for individuals, and longer for companies. Once you’ve received confirmation from Apple, you’ll be emailed a link to activate your account; when that’s done, you’re a full-fledged developer!

Downloading Xcode

To develop apps for either platform, you’ll use Xcode, Apple’s integrated development environment. Xcode combines a source code editor, debugger, compiler, profiler, iPhone and iPad simulator, and more into one package, and it’s where you’ll spend the majority of your time when developing applications.

Note

Xcode is only available for Mac.

You can get Xcode from the Mac App Store. Simply open the App Store application and search for “Xcode,” and it’ll pop up. It’s a free download, though it’s rather large (several gigabytes at the time of writing).

Once you’ve downloaded Xcode, it’s straightforward enough to install it. The Mac App Store gives you an installer to double-click. Follow the prompts to install.

Creating Your First Project with Xcode

Xcode is designed around a single window. Each of your projects will have one window, which adapts to show what you’re working on.

To start exploring Xcode, you’ll first need to create a project by following these steps:

Launch Xcode. You can find it by opening Spotlight (by pressing ⌘-Spacebar) and typing Xcode. You can also find it by opening the Finder, going to your hard drive, and opening the Applications directory. If you had any projects open previously, Xcode will open them for you. Otherwise, the Welcome to Xcode screen appears (see Figure 1-1).

Create a new project. Do this simply by clicking “Create a new Xcode project” or go to File→New→Project.

You’ll be asked what kind of application to create. The template selector is divided into two areas. On the lefthand side, you’ll find a collection of categories that applications can be in. You can choose to create an iOS or Mac project template, which sets up a project directory that will get you started in the right direction.

Because we’re just poking around Xcode at the moment, it doesn’t really matter, so choose Application under the iOS header and select Single View Application. This creates an empty iOS application.

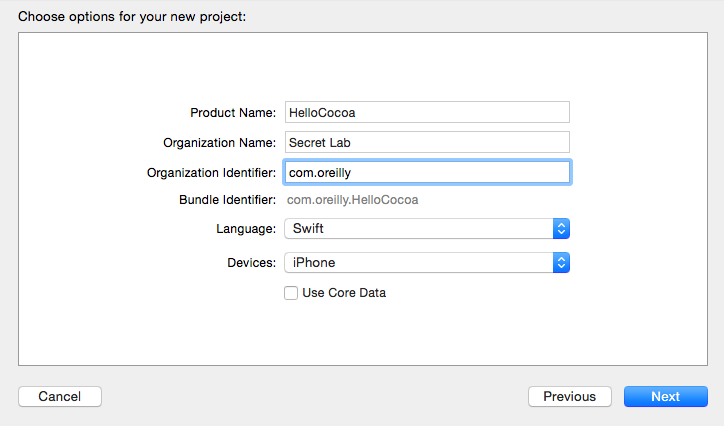

Enter information about the project. Depending on the kind of project template you select, you’ll be asked to provide different information about how the new project should be configured.

At a minimum, you’ll be asked for the following information, no matter which platform and template you choose:

- The product’s name

- This is the name of the project and is visible to the user. You can change this later.

- Your organization identifier

This is used to generate a bundle ID, a string that looks like a reverse domain name (e.g., if O’Reilly made an application named MyUsefulApplication, the bundle ID would be com.oreilly.MyUsefulApplication).

Note

Bundle IDs are the unique identifier for an application, and are used to identify that app to the system and to the App Store. Because each bundle ID must be unique, the same ID can’t be used for more than one application in either of the iOS or Mac App Stores. That’s why the format is based on domain names—if you own the site usefulsoftware.com, all of your bundle IDs would begin with com.usefulsoftware, and you won’t accidentally use a bundle ID that someone else is using or wants to use because nobody else owns the same domain name.

If you don’t have a domain name, enter anything you like, as long as it looks like a backwards domain name (e.g., com.mycompany will work).

Note

If you plan on releasing your app, either to the App Store or elsewhere, it’s very important to use a company identifier that matches a domain name you own. The App Store requires it, and the fact that the operating system uses the bundle ID that it generates from the company identifier means that using a domain name that you own eliminates the possibility of accidentally creating a bundle ID that conflicts with someone else’s.

If you’re writing an application for the Mac App Store, you’ll also be prompted for the App Store category (whether it’s a game, an educational app, a social networking app, or something else).

Depending on the template, you may also be asked for other information (e.g., the file extension for your documents if you are creating a document-aware application, such as a Mac app). You’ll also be asked which language you want to use; because this book is about Swift, you should probably choose Swift! The additional information needed for this project is in the following steps.

- Name the application. Enter “HelloCocoa” in the Product Name section.

Make the application run on the iPhone. Choose iPhone from the Devices drop-down list.

Note

iOS applications can run on the iPad, iPhone, or both. Applications that run on both are called “universal” applications and run the same binary but have different user interfaces. For this exercise, just choose iPhone.

Click Next to create the project. Leave the rest of the settings as shown in Figure 1-2.

- Choose where to save the project. You’ll be asked where to save the project. Select a location that suits you.

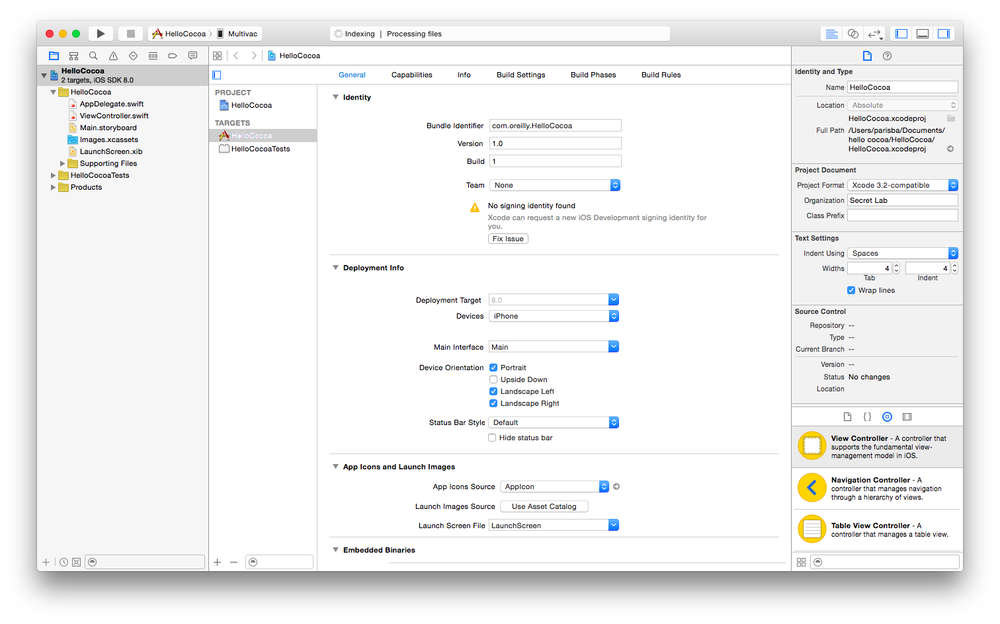

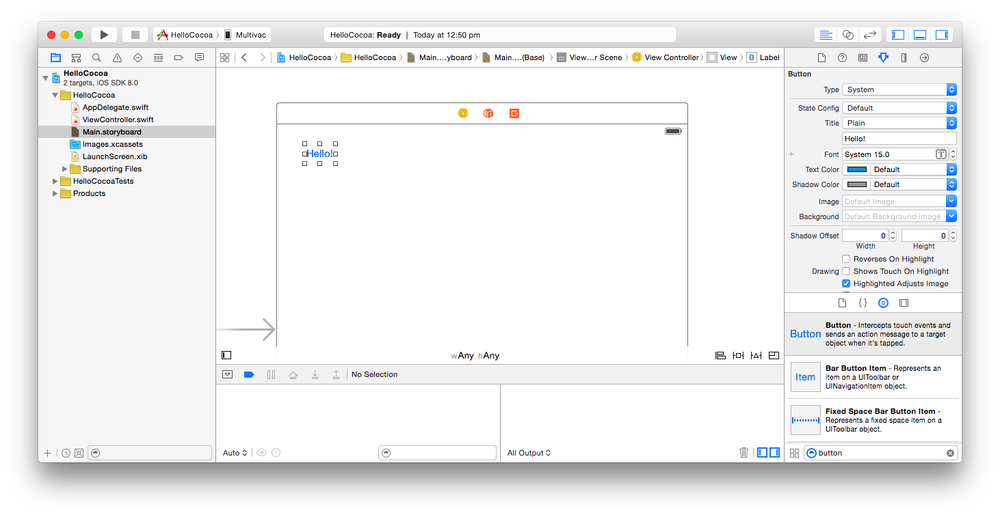

Once you’ve done this, Xcode will open the project and you can now start using the entire Xcode interface, as shown in Figure 1-3.

The Xcode Interface

As mentioned, Xcode shows your entire project in a single window, which is divided into a number of sections. You can open and close each section at will, depending on what you want to see.

Let’s take a look at each of these sections and examine what they do.

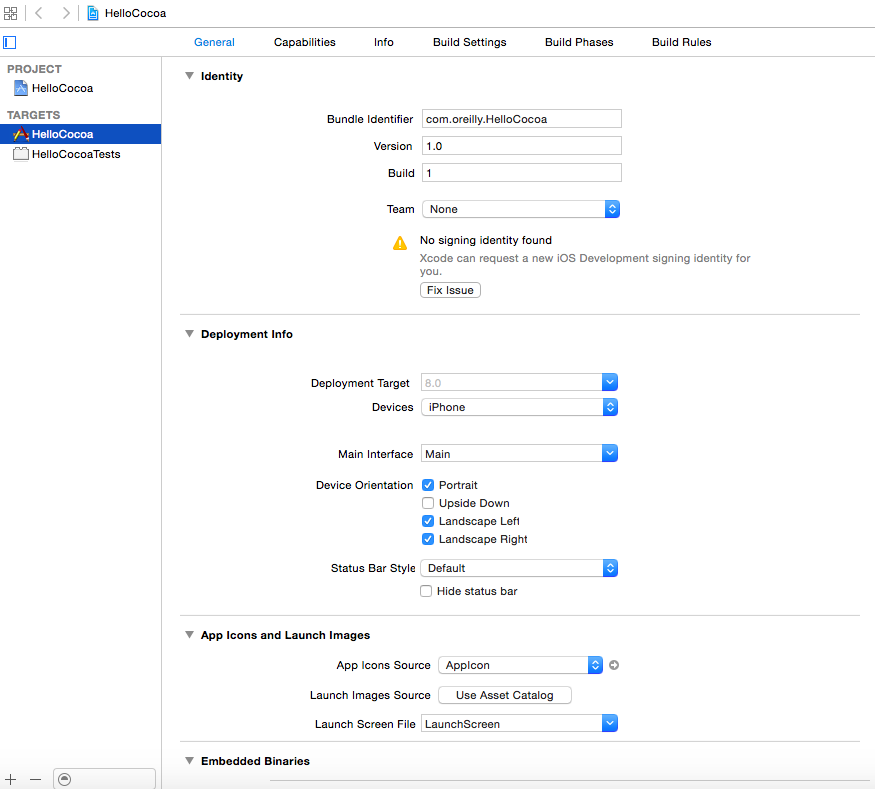

The editor

The Xcode editor (Figure 1-4) is where you’ll be spending most of your time. All source code editing, interface design, and project configuration take place in this section of the application, which changes depending on which file you currently have open.

If you’re editing source code, the editor is a text editor, with code completion, syntax highlighting, and all the usual features that developers have come to expect from an integrated development environment. If you’re modifying a user interface, the editor becomes a visual editor, allowing you to drag around the components of your interface. Other kinds of files have their own specialized editors as well.

The editor can also be split into a main editor and an assistant editor. The assistant shows files that are related to the file currently open in the main editor. It will continue to show files that have that relationship to whatever is open, even if you open different files.

For example, if you open an interface file and then open the assistant, the assistant will, by default, show related code for the interface you’re editing. If you open another interface file, the assistant will show the code for the newly opened files.

You can also jump directly from one file in the editor to its counterpart—for example, from an interface file to the corresponding implementation file. To do this, hit Control-⌘-Up Arrow to open the current file’s counterpart in the current editor. You can also hit Control-⌘-Option-Up Arrow to open the current file’s counterpart in an assistant pane.

The toolbar

The Xcode toolbar (Figure 1-5) acts as mission control for the entire interface. It’s the only part of Xcode that doesn’t significantly change as you develop your applications, and it serves as the place where you can control what your code is doing.

From left to right, after the OS X window controls, the toolbar features the following items:

- Run button

Clicking this button instructs Xcode to compile and run the application. Depending on the kind of application you’re running and your currently selected settings, this button will have different effects:

- If you’re creating a Mac application, the new app will appear in the Dock and will run on your machine.

- If you’re creating an iOS application, the new app will launch in either the iOS Simulator or on a connected iOS device, such as an iPhone or iPad. Additionally, if you click and hold this button, you can change it from Run to another action, such as Test, Profile, or Analyze. The Test action runs any unit tests that you have set up; the Profile action runs the application Instruments (see Chapter 17); and the Analyze action checks your code and points out potential problems and bugs.

- Stop button

- Clicking this button stops any task that Xcode is currently doing—if it’s building your application, it stops, and if your application is currently running in the debugger, it quits it.

- Scheme selector

- Schemes are what Xcode calls build configurations—that is, what’s being built and how. Your project can contain multiple targets, which are the final build products created by your application. Targets can share resources like code, sound, and images, allowing you to more easily manage a task like building an iOS version of a Mac application. You don’t need to create two projects, but rather have one project with two targets that can share as much code as you prefer. To select a target, click on the lefthand side of the scheme selector. You can also choose where the application will run. If you are building a Mac application, you will almost always want to run the application on your current Mac. If you’re building an iOS application, however, you have the option of running the application on an iPhone simulator or an iPad simulator. (These are in fact the same application; it simply changes shape depending on the application that is run inside it.) You can also choose to run the application on a connected iOS device if it has been set up for development.

- Status display

- The status display shows what Xcode is currently doing—building your application, downloading documentation, installing an application on an iOS device, and so on. If there is more than one task currently in progress, a small button will appear on the lefthand side, which cycles through the current tasks when clicked.

- Editor selector

- The editor selector determines how the editor is laid out. You can choose to display either a single editor, the editor with the assistant, or the versions editor, which allows you to compare different versions of a file if you’re using a revision control system like Git or Subversion.

Note

We don’t have anywhere near the space needed to talk about using version control in your projects in this book, but it’s an important topic. We recommend Jon Loeliger and Matthew McCullough’s Version Control with Git, 2nd Edition (O’Reilly).

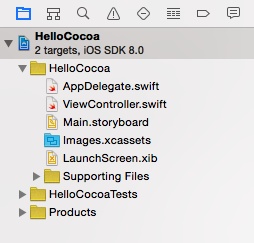

The navigator

The lefthand side of the Xcode window is the navigator, which presents information about your project (Figure 1-6).

The navigator is divided into eight tabs, from left to right:

- The project navigator gives you a list of all the files that make up your project. This is the most commonly used navigator, as it determines what is shown in the editor. Whatever is selected in the project navigator is opened in the editor.

- The symbol navigator lists all the classes and functions that exist in your project. If you’re looking for a quick summary of a class or want to jump directly to a method in that class, the symbol navigator is a handy tool.

- The search navigator allows you to perform searches across your project if you’re looking for specific text. (The shortcut is ⌘-Shift-F. Press ⌘-F to search the current open document.)

- The issue navigator lists all the problems that Xcode has noticed in your code. This includes warnings, compilation errors, and issues that the built-in code analyzer has spotted.

- The test navigator shows all the unit tests associated with your project. Unit tests used to be an optional component of Xcode, but are now built into Xcode directly. Unit tests are discussed in The Testing Framework.

- The debug navigator is activated when you’re debugging a program, and it allows you to examine the state of the various threads that make up your program.

- The breakpoint navigator lists all of the breakpoints that you’ve currently set for use while debugging.

- The report navigator lists all the activity that Xcode has done with your project (such as building, debugging, and analyzing). You can go back and view previous build reports from earlier in your Xcode session, too.

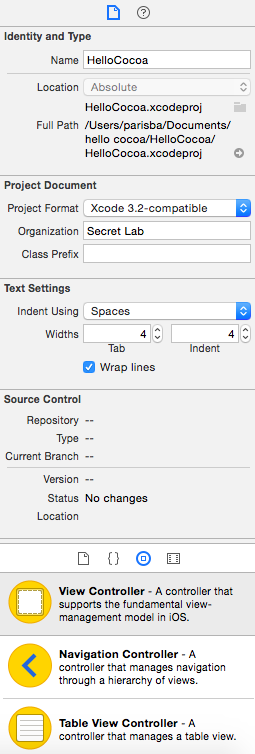

Utilities

The Utilities pane (Figure 1-7) shows additional information related to what you’re doing in the editor. If you’re editing an interface, for example, the Utilities pane allows you to configure the currently selected user interface element.

The Utilities pane is split into two sections: the inspector, which shows extra details and settings for the currently selected item, and the library, which is a collection of items that you can add to your project. The inspector and the library are most heavily used when building user interfaces; however, the library also contains a number of useful items such as file templates and code snippets, which you can drag and drop into place.

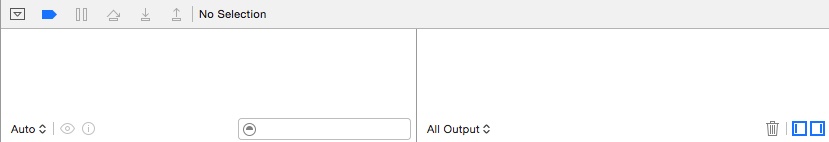

The debug area

The debug area (Figure 1-8) shows information reported by the debugger when the program is running. Whenever you want to see what the application is reporting while running, you can view it in the debug area.

The area is split into two sections: the lefthand side shows the values of local variables when the application is paused; the righthand side shows the ongoing log from the debugger, which includes any logging that comes from the debugged application.

Developing a Simple Swift Application

Let’s jump right into working with Xcode. We’ll begin by creating a simple iOS application and then connect it together. If you’re more interested in Mac development, don’t worry—the same techniques apply.

This sample application will display a single button that, when tapped, will pop up an alert and change the button’s label to “Test!” We’re going to build on the project we created earlier, so make sure you have that project open.

It’s generally a good practice to design the interface first and then add code. This means that your code is written with an understanding of how it maps to what the user sees.

To that end, we’ll start by designing the interface for the application.

Designing the Interface

When building an application’s interface using Cocoa and Cocoa Touch, you have two options. You can either design your application’s screens in a storyboard, which shows how all the screens link together, or you can design each screen in isolation. This book covers storyboards in more detail later; for now, this first application has only one screen, so it doesn’t matter much either way.

Start by opening the interface file and adding a button. These are the steps you’ll need to follow:

First, open the main storyboard. Because newly created projects use storyboards by default, your app’s interface is stored in the Main.storyboard file.

Open it by selecting it in the project navigator. The editor will change to show the application’s single, blank screen.

Next, drag in a button. We’re going to add a single button to the screen. All user interface controls are kept in the object library, which is at the bottom of the Utilities pane on the righthand side of the screen.

To find the button, you can either scroll through the list until you find Button, or type “button” in the search field at the bottom of the library.

Once you’ve located it, drag it into the screen.

At this point, we need to configure the button. Every item that you add to an interface can be configured. For now, we’ll only change the label.

Select the new button by clicking it, and select the Attributes Inspector, which is the third tab from the right at the top of the Utilities pane. You can also reach it by pressing ⌘-Option-4.

Change the button’s Title to “Hello!”

Note

You can also change the button’s title by double-clicking it in the interface.

Our simple interface is now complete (Figure 1-9). The only thing left is to connect it to code.

Connecting the Code

Applications aren’t just interfaces—as a developer, you also need to write code. To work with the interface you’ve designed, you need to create connections between your code and your interface.

There are two kinds of connections that you can make:

- Outlets are variables that refer to objects in the interface. Using outlets, you can instruct a button to change color or size, or hide itself. There are also outlet collections, which allow you to create an array of outlets and choose which objects it contains in the Interface Builder.

- Actions are methods in your code that are run in response to the user interacting with an object. These interactions include the user touching a finger to an object, dragging a finger, and so on.

To make the application behave as we’ve just described—tapping the button displays a label and changes the button’s text—we’ll need to use both an outlet and an action. The action will run when the button is tapped, and will use the outlet connection to the button to modify its label.

To create actions and outlets, you need to have both the interface editor and its corresponding code open. Then hold down the Control key and drag from an object in the interface editor to your code (or to another object in the interface editor, if you want to make a connection between two objects in your interface).

We’ll now create the necessary connections:

First, open the assistant. To do this, select the second tab in the editor selector in the toolbar.

The assistant should show the corresponding code for interface ViewController.swift. If it doesn’t, click the interwining circles icon (which represents the assistant) and navigate to Automatic→ViewController.swift.

Create the button’s outlet. Hold down the Control key and drag from the button into the space below the first

{in the code.A pop-up window will appear. Leave everything as the default, but change the Name to “helloButton.” Click Connect.

A new line of code will appear: Xcode has created the connection for you, which appears in your code as a property in your class.

Create the button’s action. Hold down the Control key, and again drag from the button into the space below the line of code we just created. A pop-up window will again appear.

This time, change the Connection from Outlet to Action. Set the Name to

showAlert. Click Connect.A second new line of code will appear. Xcode has created the connection, which is a method inside the

ViewControllerclass.-

In the

showAlertmethod you just created, add in the new code:

@IBActionfuncshowAlert(sender:AnyObject){varalert=UIAlertController(title:"Hello!",message:"Hello, world!",preferredStyle:UIAlertControllerStyle.Alert)alert.addAction(UIAlertAction(title:"Close",style:UIAlertActionStyle.Default,handler:nil))self.presentViewController(alert,animated:true,completion:nil)self.helloButton.setTitle("Clicked",forState:UIControlState.Normal)}

This code creates a UIAlertController, which displays a message to the user

in a pop-up window. It prepares it by setting its title to “Hello!” and the

text inside the window to “Hello, world!” The alert is then shown to the

user. Finally, an action (doing nothing but dismissing the alert in this case) is added with the text “Click.” It then sets the title of the button to “Clicked.”

The application is now ready to run. Click the Run button in the upper-left corner. The application will launch in the iPhone simulator.

Note

If you happen to have an iPhone or iPad connected to your computer, Xcode will by default try to launch the application on the device rather than in the simulator. To make Xcode use the simulator, go to the Scheme menu in the upper left corner of the window and change the currently selected scheme to the simulator.

When the app finishes launching in the simulator, tap the button. An alert will appear; when you close it, you’ll notice that the button’s text has changed.

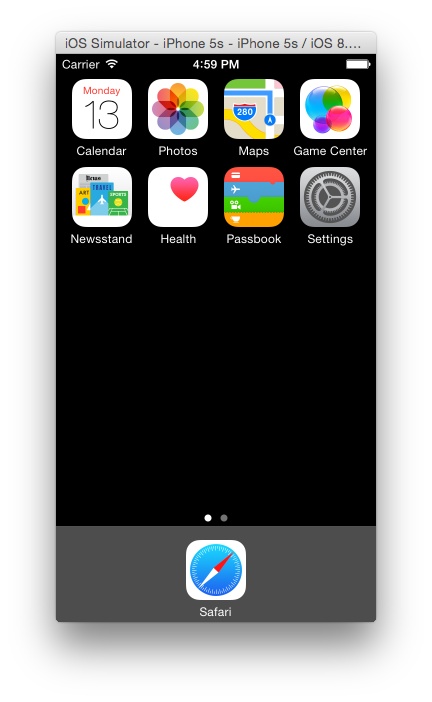

Using the iOS Simulator

The iOS Simulator (Figure 1-10) allows you to test out iOS applications without having to mess around with devices. It’s a useful tool, but keep in mind that the simulator behaves very differently compared to a real device.

For one thing, the simulator is a lot faster than a real device and has a lot more memory. That’s because the simulator makes use of your computer’s resources—if your Mac has 8 GB of RAM, so will the simulator, and if you’re building a processor-intensive application, it will run much more smoothly on the simulator than on a real device.

The iOS Simulator can simulate many different kinds of devices: everything from the iPad 2 to the latest iPads, and from the Retina display 3.5- and 4-inch iPhone-sized devices to the latest 4.7-inch and 5.5-inch iPhones.

To change the device, open the Hardware menu, choose Device, and select the device you want to simulate. You can also change which simulator to use via the scheme selector in Xcode.

You can also simulate hardware events, such as the home button being pressed or the iPhone being locked. To simulate pressing the home button, you can either click the virtual button underneath the screen, choose Hardware→Home, or press ⌘-Shift-H. To lock the device, press ⌘-L or choose Hardware→Lock.

Note

If there’s no room on the screen, the simulator won’t show the virtual hardware buttons. So if you want to simulate the home button being pressed, you need to use the keyboard shortcut ⌘-Shift-H.

There are a number of additional features in the simulator, which we’ll examine more closely as they become relevant to the various parts of iOS we’ll be discussing.

Testing iOS Apps with TestFlight

TestFlight is a service operated by Apple that allows you to send copies of your app to people for testing. Using TestFlight, you can send builds of your app to people in your organization and up to 1,000 external testers.

TestFlight allows you to submit testing builds to up to 25 people who are members of your Developer Program account. Additionally, you can send the app to up to a thousand additional people for testing, once the app is given a preliminary review by Apple.

To use TestFlight, you configure the application in iTunes Connect by providing information like the app’s name, icon, and description. You also create a list of users who should receive the application. You then upload a build of the app through Xcode, and Apple emails them a link to download and test it.

For more information on how to use TestFlight, see the iTunes Connect documentation.

Get Swift Development with Cocoa now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.