The beauty of life in the Era of Switchers is that most of the big-boy programs are available in nearly identical versions for both the Mac and Windows. Word, Excel, and PowerPoint; Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign; FileMaker Pro; Dreamweaver; and many other programs are available for both Mac and Windows. Sometimes you have to buy the Mac version separately; sometimes it’s on the same CD.

The best part: The documents you create with the Mac versions are generally identical in format to the ones created in Windows. A Microsoft Word document, for example, requires no conversion when transferred from a Mac to a PC or vice versa. It is what it is—a .doc or .docx file.

Same thing with Excel spreadsheets (.xls), PowerPoint slideshows (.ppt), Photoshop documents (.psd), and on and on. You may occasionally encounter a tiny formatting difference—a line thickness change, a movie file that requires a plug-in—but most documents open flawlessly when moved between Macs and PCs. (Chapter 7 offers more detail on finding Mac versions of your favorite PC programs.)

But even if switching to the Mac OS X versions of your programs is relatively easy, learning how Mac OS X programs in general operate may require some study. As this chapter will make clear, the relationship between programs and their documents differs in several substantial ways from the way things work in Windows.

Many of the techniques for launching (opening) a program work just as they do in Windows. For example:

Click a program’s icon on the Dock, the Sidebar, or the Finder toolbar.

Use Spotlight. Hit ⌘-space bar, type the first letters of the program’s name, and then press Return.

Double-click an application’s icon in the Finder.

Highlight an application icon and then press ⌘-O (short for File→Open) or ⌘-↓.

Use the submenus of the

menu’s Recent Items→Applications command.

menu’s Recent Items→Applications command.Open a document icon in any of these ways, or drag a document onto the icon of a program that can open it (whether in the Dock, the Finder toolbar, the Sidebar, or in a folder window).

When you launch a program, the Mac reads its computer code, which lies on your hard drive’s surface, and feeds it quickly into RAM (memory). During this brief interval, the icon of the opening program jumps up and down eagerly in your Dock.

What happens next depends on the program you’re using. Most present you with a new, blank, untitled document. Some, like iDVD, automatically open the last file you worked on. Some, like FileMaker and PowerPoint, ask if you want to open an existing document or create a new one.

And a few oddball programs don’t open any window at all when first launched.

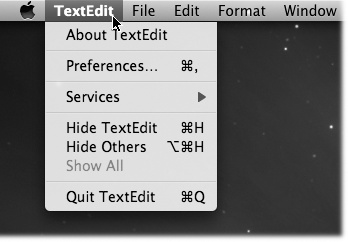

In each case, however, the very first menu after the ![]() appears with bold lettering and identifies the program you’re using. It might say iTunes, or Microsoft Word, or Stickies.

appears with bold lettering and identifies the program you’re using. It might say iTunes, or Microsoft Word, or Stickies.

This Application menu (Figure 4-1) offers a number of commands pertaining to the entire program and its windows, including About, Quit, and Hide.

In Macintosh lingo, you don’t “exit” a program when you’re finished with it, you “quit” it. And the command to do so isn’t in the File menu—it’s at the bottom of the Application menu.

But Mac OS X offers two much more fun ways to quit a program:

Right-click a program’s Dock icon and then choose Quit from the pop-up menu.

When you’ve pressed ⌘-Tab to summon the “heads-up display” of open programs, type the letter Q without releasing the ⌘ key. The highlighted program quits without further ado.

Mac OS X is a rock-solid operating system, but that doesn’t mean programs never screw up. Individual programs are as likely as ever to freeze—or, rather, to hang (to lock up and display the “spinning beach ball of death” cursor). In such cases, you have no choice but to force-quit the program—or, in Windows lingo, to terminate it or “end its task.”

Doing so doesn’t destabilize your Mac; you don’t have to restart it. In fact, you can usually reopen the very same program and get on with your life.

You can force-quit a stuck program in any of several ways:

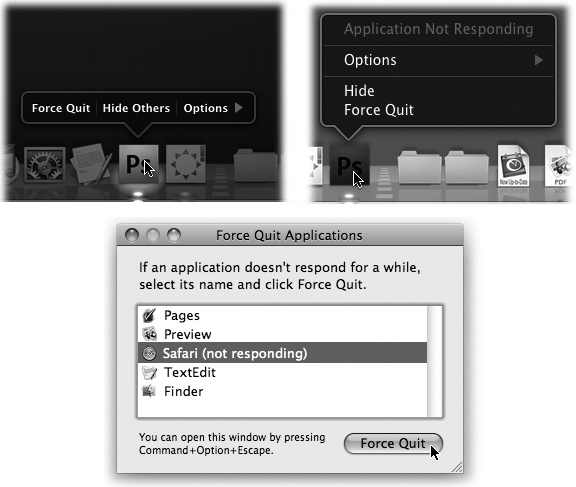

Click-and-hold on the program’s Dock icon. That triggers the Exposé function, of course, but it also offers a Quit button just above your cursor. Press the Option key to make the button say Force Quit (Figure 4-2 left). Click it.

Control-click (right-click) its Dock icon. Once the shortcut menu appears, press Option so that the Quit command now says Force Quit (Figure 4-2 bottom). Bingo—that program is outta here.

Figure 4-2. Top: Thanks to the Option key, you can force quit a program from the Dock—either by click-and-holding (left) or Control-clicking (right). Bottom: When you press Option-⌘-Esc or choose Force Quit from the

menu, a tidy box listing all open programs appears. Just click the one you want to abort, click Force Quit, and click Force Quit again in the confirmation box. (Using more technical tools like the Unix kill command, there are other ways to jettison programs. But these are often the most convenient.)

menu, a tidy box listing all open programs appears. Just click the one you want to abort, click Force Quit, and click Force Quit again in the confirmation box. (Using more technical tools like the Unix kill command, there are other ways to jettison programs. But these are often the most convenient.)Press Option-⌘-Esc, the traditional Mac force-quit keystroke, or choose

→Force Quit. Either way, proceed as shown in Figure 4-2.

→Force Quit. Either way, proceed as shown in Figure 4-2.

Again, force-quitting is not bad for your Mac. The only downside to force-quitting a program is that you lose any unsaved changes to your open documents, along with any preference settings you may have changed while the program was open.

Just as in Windows, there’s a handy keystroke for switching from one open program to another; it’s the ⌘-Tab keystroke (see Figure 4-3).

You can use this feature in three different ways, which are well worth learning:

If you keep the ⌘ key pressed, each press of the Tab key highlights the Dock icon of another program, in left-to-right Dock order. Release both keys when you reach the one you want. Mac OS X brings the corresponding program to the front. (To move backward through the open programs, press Shift-⌘-Tab.)

If you leave the ⌘ key pressed, you can choose a program by clicking its icon with your mouse.

A single press of ⌘-Tab takes you to the program you used most recently, and another, separate ⌘-Tab bounces back to the program you started in.

Figure 4-3. Apple calls this row of open program icons a “heads-up display,” named after the projected data screens on a Navy jet windshield that lets pilots avoid having to look down at their instruments.

Imagine you’re doing a lot of switching between two programs—your Web browser and your email program, for example. If you have five other programs open, you don’t waste your time ⌘-Tabbing your way through all open programs just to “get back” to your Web browser.

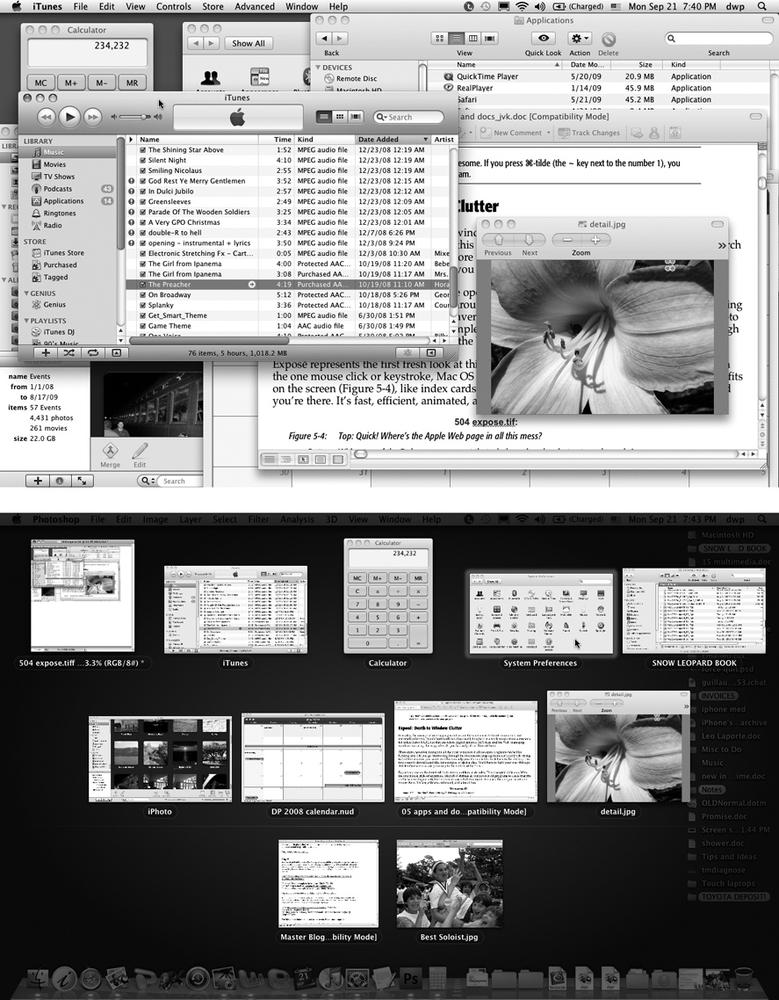

Managing all the open windows in all the open programs used to be like herding cats. Off you would go, burrowing through the microscopic pop-up menus of your Dock, trying to find the window you want.

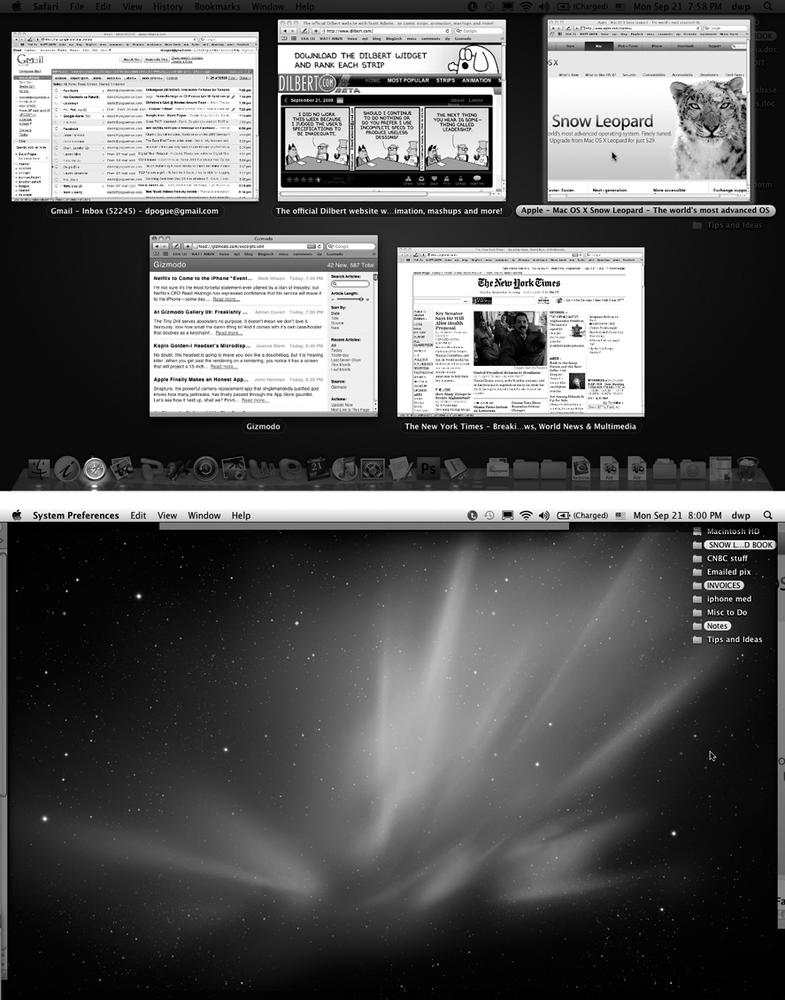

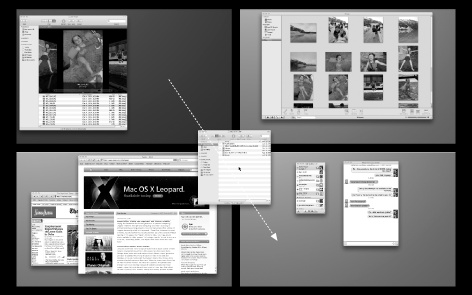

Exposé represents the first fresh look at this problem in decades. The concept is delicious: With the one mouse click or keystroke, Mac OS X shrinks all windows in all programs to a size that fits on the screen (Figure 4-4), like index cards on a bulletin board. You click the one you want, and you’re there. It’s fast, efficient, animated, and a lot of fun.

Now, this is going to get very mind-blowing very fast, so read slowly and keep your shoulders relaxed.

There are actually three different Exposé modes. One shows you miniatures of all windows in all programs; one shows you miniatures of all the windows in just one program; and one hides all windows in all programs so you can see the desktop.

Each of these three modes, moreover, can be triggered using different combinations of the mouse and keyboard. The following pages will cover all of them, but you’re not expected to learn all that. Just find the one trigger that seems most convenient, and stick with it.

The first and most famous Exposé method is shown in Figure 4-4. Every window in every program is arrayed before you, nothing covered up, nothing hidden. It’s a great way to get your bearings in a hurry.

Here are the best ways to get this effect:

Current keyboards: Press F3 (

). On recent Apple laptop and desktop keyboards—aluminum with very flat, thin keys poking up—the F3 key is dedicated to Exposé. It’s even painted with a special Exposé logo (

). On recent Apple laptop and desktop keyboards—aluminum with very flat, thin keys poking up—the F3 key is dedicated to Exposé. It’s even painted with a special Exposé logo ( ). Tap that key to get the all-apps Exposé effect.

). Tap that key to get the all-apps Exposé effect.Figure 4-4. Top: Quick! Where’s System Preferences in all this mess? Bottom: With a tap of the F3 key, you can spot that window, shrunken but not overlapped. Each thumbnail window offers a label to help you identify it. These aren’t static snapshots of the windows at the moment you Exposé'd them. They’re live, still-updating windows, as you’ll discover if one of them contains a playing QuickTime movie or a Web page that’s still loading. If you’re not pointing to a window, tapping F3 again turns off Exposé without changing anything; if you’re pointing to a window, tapping F3 again brings it forward.

Plastic keyboards: Press F9. On older keyboards, the white or black plastic ones, press F9 instead.

Laptops: Swipe downward with four fingers. Sounds contrived, it’s true. But giving your trackpad a four-finger swipe is a quick and easy way to trigger all-apps Exposé. (Then you can get back to what you were doing by swiping upward with four fingers.)

Note

Older Mac laptops don’t have multitouch trackpads and therefore don’t offer this four-finger option. To find out if yours is eligible—and to make sure the four-finger swiping feature is turned on—open System Preferences→Trackpad. Confirm that there’s a list of gestures at the left side of the panel, as shown on On, Off, and Sleep.

As you can read later in this section, you can also trigger all-apps Exposé by pressing special buttons on your mouse, or by flinging the cursor into a specified corner of the screen. But start with baby steps.

To exit Exposé, click one of the miniaturized windows, or repeat any of the Exposé triggers.

Note

If you’ve minimized a program’s windows, they now show up in Exposé, too—as miniatures below a fine horizontal line. You can see the effect in Figure 4-4.

A second Exposé function is designed to present miniatures of all windows only in the program you’re using—great when you’re Web browsing or word processing. All the program’s windows spread out, and shrink if necessary, so you can click the one you want (Figure 4-5 top).

Figure 4-5. Top: When you trigger one-app Exposé, you get a clear shot at any window in the current program (Safari, in this example). In the meantime, the rest of your screen attractively dims, as though someone has just shined a floodlight onto the windows of the program in question. It’s a stunning effect. Bottom: Trigger desktop Exposé when you need to duck back to the desktop for a quick administrative chore. Here’s your chance to find a file, throw something away, eject a disk, or whatever, without having to disturb your application windows. In either case, tap the same function key again to turn off Exposé. Or click one of the window edges, which you can see peeking out from all four edges of the screen.

Here’s how Apple intends most people to trigger this option:

Current keyboards: Press Control-F3. That’s the keystroke on current laptops and desktops, the ones with aluminum keyboards.

Tip

As noted in the box on All-Apps Exposé, you can also press Fn-F10, or with some tweaking, F10 alone. Or you can change the keystroke altogether as described on Changing a Menu Keyboard Shortcut.

Plastic keyboards: Press F10.

Use Dock Exposé. That is, click any program’s Dock icon and hold the button down for half a second.

This feature has one chief advantage over the keystroke method: You can Exposé-ize any program’s windows, not just the one you’re using at the moment.

The third flavor of Exposé is surprisingly handy. It sends all windows in all programs cowering to the edges of your screen, revealing the desktop beneath in all its uncluttered splendor (Figure 4-5 bottom).

Here’s the keystroke scheme:

Current keyboards: Press ⌘-F3. That’s the trigger for aluminum keyboards and laptops.

Note

Once again, you can also press Fn-F11, or (if you set it up) F11 by itself. See the box on All-Apps Exposé.

Plastic keyboards: Press F11.

The windows fly off to the edges of the screen, where they remain—forever, or until you tap the keystroke again, click a visible window edge, double-click an icon, or take some other window-selection step.

This is a spectacular opportunity to save headache and hassle in situations like these:

You’re writing an email message, and you want to attach a file. Tap the desktop Exposé keystroke, root around in the Finder until you locate the file you want. Begin to drag it, and then, without releasing the mouse button, tap the desktop Exposé keystroke again to bring back your email window. (Or drag the attachment directly onto your email program’s icon on the Dock and pause until its window thumbnails appear.)

Move your cursor, with the file in mid-drag, directly over the outgoing message window; release the cursor to create the attachment. You’ve just added an attachment from the desktop in one smooth motion.

You want to open a different document. For many people, having access to the entire Finder beats the pants off having to use the Open dialog box. Double-clicking the icon you want automatically opens it and turns off Exposé.

You’re on the Web, and you want to see if some file has finished downloading. Trigger desktop Exposé to survey the situation on your desktop.

If the layer of open programs is the atmosphere, the Finder is the earth below—and the ability to teleport you back and forth is a huge timesaver.

Just having your world o’ windows spread out like index cards is magic enough. But these windows are live. You can work with them. Let us count the ways:

Tab through Exposé'd apps. Once you’ve started one-app Exposé, and a program’s windows are arrayed before you, tap the Tab key to switch to the next running program. All its windows spring to the fore. Tab, Tab, Tab through all your open programs. (Shift-Tab, as usual, cycles through the programs in the opposite direction.)

Enter Exposé from the heads-up display. The New, Improved “Alt-Tab” describes the heads-up display—the Mac OS X application switcher, the row of “these are your open programs” icons—which appears when you press ⌘-Tab.

The cool thing is that once you’ve got that heads-up display open, you can press ↑, or ↓ to enter Exposé for whatever program’s icon is highlighted! From there, release the keys and hit Tab to cycle through your open apps.

Hold down instead of two presses. Most of the time, you’ll probably use Exposé in two steps. You’ll tap the keystroke once to get the windows out of the way, and tap it again to bring them back (if, indeed, you haven’t clicked a window to bring them back).

In some cases, though, you may find it easier to hold down the relevant key. For example, hold down ⌘-F3 to see if a file is finished copying to the desktop, then release the keys to bring back all of the windows. (Actually, you can let go of the ⌘ key as soon as you’ve entered Exposé.) For quick window-clearing situations, that method saves you the step of having to press the key a second time to turn off Exposé.

Use the spring-loaded Dock. This trick is great when you want to drop a file from one program into a particular window belonging to another.

The most common example: You want to add an attachment to an outgoing email message. In the Finder, locate the file’s icon. Drag it directly onto your email program’s Dock icon—and pause with your finger still on the button. After a half second, Exposé happens, showing all your email program’s open windows. Now continue your drag onto the miniaturized window of the outgoing message so it’s highlighted, tap the space bar to open it, and release. Presto! The file is attached.

This trick also works great when you want to drop a photo into a newsletter, for example, or a text clipping into a word processing document.

Sort the windows. That’s right: you can sort the windows as they appear on the screen. Press ⌘-1 to sort the window names alphabetically, or ⌘-2 to sort them according to the programs they belong to.

The trouble with miniaturized windows is that, well, they’re miniaturized. The more windows you’ve Exposé'd, the smaller they are, and the harder it is to see what’s in them.

Fortunately, your old friend Quick Look (Quick Look) is standing by to help.

Once you’ve got shrunken windows on the screen (using all-apps Exposé or one-app Exposé), tap your arrow keys to highlight a window (or point with your mouse without clicking). You’ll see a bright-blue border move from window to window.

At any point, you can press the space bar to make that one window return to life size. You haven’t really activated it—you can’t edit it—but at least you can see it at full size.

And here’s the very cool part. Once you’ve triggered Quick Look like this, you can press the arrow keys to zap other mini windows back to full size, without having to exit Quick Look. Or, again, point to other windows without clicking. Each zooms in to 100 percent size. (All of this is much easier to do than to imagine.)

You can keep examining your windows at full size until you spot the one you’re after; now tap Return (or click the mouse in the window) to exit Quick Look and Exposé. You’ve just opened that window, and you’re ready to roll.

Exposé is wonderful and all, but the standard keys for triggering its three functions may leave something to be desired. For one thing, they might already be “taken” by other functions in your programs (like Microsoft Word) or even by your computer. For another thing, those keys are at the top of the keyboard where your typing fingers aren’t used to going, and you may have to hunt to make sure you’re pressing the right one.

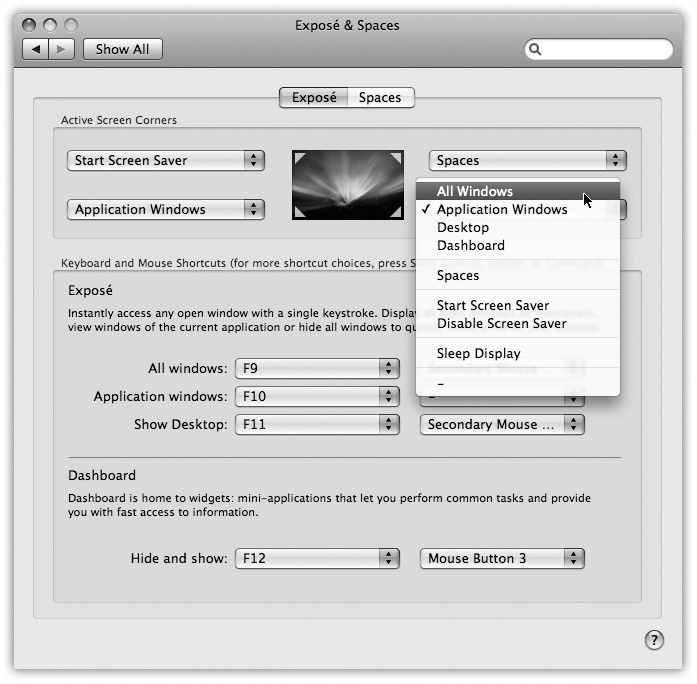

Fortunately, you can reassign the Exposé functions to a huge range of other keys, with or without modifiers like Shift, Control, and Option. To view your options, choose ![]() →System Preferences and then click the Exposé & Spaces icon (Figure 4-6).

→System Preferences and then click the Exposé & Spaces icon (Figure 4-6).

Here, you’ll discover that you can trigger Exposé’s functions in any of three ways:

The four pop-up menus (Figure 4-6) represent the four corners of your screen. Using these menus, you can assign an Exposé trigger to each corner; for example, if you choose Desktop from the first pop-up menu, when your pointer hits the upper-left corner of the screen, you’ll hide all windows and expose the desktop. (To make the windows come back, click any visible edge of a window, highlight a window thumbnail and press Return, or twitch the cursor back into the same corner.)

Figure 4-6. You can trigger Exposé in any of three ways: by twitching your cursor into a certain corner of the screen (top), pressing a key (lower left), or clicking the extra buttons on a multibutton mouse (lower right), including Apple’s Mighty Mouse or Magic Mouse. Of course, there’s nothing to stop you from setting up all three ways, so you can press in some situations and twitch or click in others.

Depending on the size of your screen, this option can feel awkward at first. But if you’ve run out of keystrokes that aren’t assigned to other functions, be glad that Apple offers you this alternative.

Also in the Exposé preferences, you’ll find three pop-up menus—“All windows,” “Application windows,” and “Show Desktop”—that correspond to the three functions of Exposé as described above. (The fourth pop-up menu, Dashboard, is described at the end of this chapter.) You can’t assign any old keystroke to Exposé, but you have far more options than the puny F9, F10, and F11 keys (or the variations on F3).

Within each pop-up menu, for example, you’ll discover that all your F-keys—F1, F2, F3, and so on—are available as triggers. If, while the pop-up menu is open, you press one or more of your modifier keys (Shift, Option, Control, or ⌘), all these F-key choices change to reflect the key you’re pressing; now the pop-up menu says Shift-F1, Shift-F2, Shift-F3, and so on. That’s how you can make Shift- F1 trigger the hide-all-windows function, for example.

These pop-up menus also contain choices like Left Shift, which refers to the Shift key on the left side of your keyboard. That is, instead of pressing F9 to make all your windows shrink, you could simply tap the Shift key.

Note

This is only an example. Repeat: This is only an example. Actually using the Shift key to shrink all your windows is a terrible, terrible idea, as you’ll quickly discover the next time you try to type a capital letter. This feature is intended exclusively for hunt-and-peck typists who never use the Shift key on one side.

If you have a laptop, you’ll also find out that you can tap the Fn key alone for Exposé—and this time, it’s a great choice, because Fn otherwise has very little direction in life.)

If your mouse has more than one button, you see a second column of pop-up menus in System Preferences. Each pop-up menu offers choices like Right Mouse Button, Middle Mouse Button, and so on. Use these pop-up menus to assign the three Exposé modes (or Dashboard) to the various clickers on your mouse: right-click to hide all windows, left-side click to reveal the desktop, and so on.

Note, by the way, that on a laptop, for example, the wording isn’t “right mouse button”—it’s “secondary mouse button.” Which means “right-click.” Which means that on a laptop, you can set it up so that a “right-click” trackpad gesture triggers Exposé. See That One-Button Mouse for all the different ways you can trigger a right-click.

Exposé is pretty darned cool. But Mac OS X offers another radical step forward in window management that you may even come to prefer. It’s called Spaces.

This feature gives you two, four, six, eight, or even 16 full-size monitors. Ordinarily, of course, attaching so many screens to a single computer would be a massively expensive proposition, not to mention the number it would do on your living space and personal relationships.

But the bonus monitors that Spaces gives you are virtual. They exist only in the Mac’s little head. You can look at only one at a time; you switch using a keystroke, a menu, or the mouse. Instead of shuffling through your windows using Exposé, you can now leave them all spread out over a much larger virtual desktop.

Just because the Spaces screens are simulated doesn’t mean they’re not useful, though. You can dedicate each one to a different program or kind of program. Screen 1 might contain your email and chat windows, arranged just the way you like them. Screen 2 can hold Photoshop, with an open document and the palettes carefully arrayed. On Screen 3: your Web browser in full-screen mode.

You can also have the same program running on multiple screens—but different documents or projects open on each one.

Now, virtual screens aren’t a new idea—this sort of software has been available for the Mac and Windows for years. But it’s never before been a standard feature of an operating system.

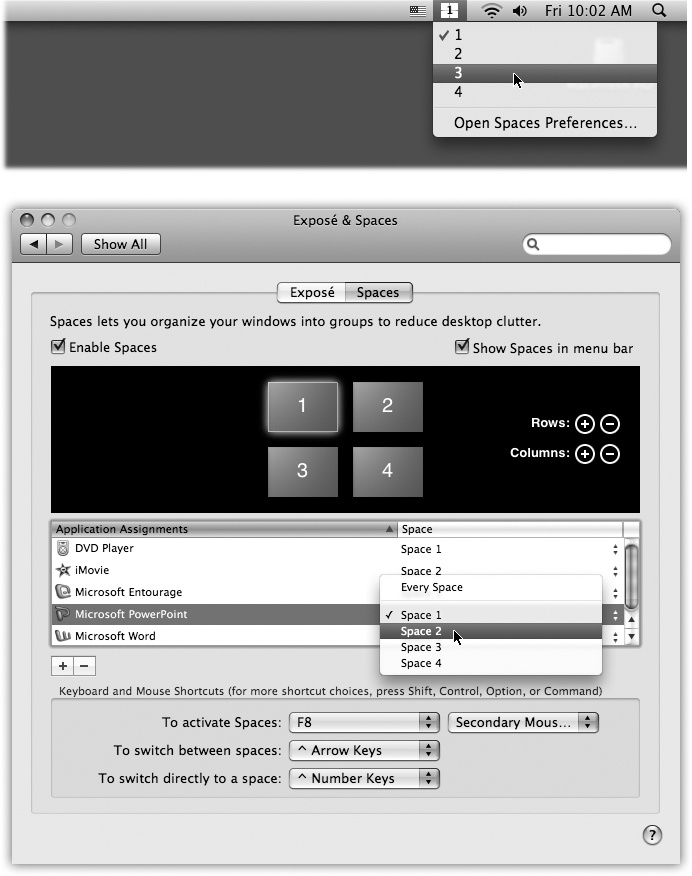

To “install” your new monitors, start by choosing ![]() →System Preferences. Click the Exposé & Spaces icon, then click the Spaces tab. You see something like Figure 4-7.

→System Preferences. Click the Exposé & Spaces icon, then click the Spaces tab. You see something like Figure 4-7.

The setup ritual goes like this:

Turn Spaces on. The “Enable Spaces” checkbox is the master on/off switch.

Add the menulet. Turn on “Show Spaces in menu bar” to make a menu of your virtual screens appear in the menu bar. It not only lets you switch screens, but the numeral on it also reminds you which screen you’re on.

Add rows or columns. Click the + and - buttons to add rows or columns of virtual monitors. There’s a difference between rows and columns, by the way. Not only will you eventually learn to sense where your various window setups live, but you can also move from one screen to another by bumping the mouse against the corresponding edge of your current screen—and you’ll need to know which edge.

Set up program auto-screen assignments. Spaces starts to become truly useful only when you make it part of your routine. You’ll eventually memorize where everything is: Web stuff, top left. Email, top right. Photoshop, lower left. Finder with Applications folder open, lower right.

For that reason, you can use the controls in the center of the System Preferences pane to specify onto which screen certain programs automatically go when they open. Click the + button to view your Applications folder. Double-click a program’s icon to make it appear in the list. Now use the pop-up menu in the Space column to indicate which space you want this program to live on, as shown in Figure 4-7.

Tip

You can also choose All Spaces, meaning that this program’s windows are available on every virtual screen. That’s handy if it’s something you use constantly, like a stock ticker or your phone-book program.

Figure 4-7. Use the controls at the top to specify how many virtual screens you want—how many rows, how many columns, up to 16 in all. Use the middle section to specify where you want particular programs to appear (that is, on which screen) when they open. Use the bottom controls to set up how you want to move from one screen to another.

To make a program stop opening into a certain screen, click its name, and then click the - button.

Set up keyboard or mouse triggers. Once you’ve got your majestic array of Cineplex Displays assembled, you need a way to move among them.

Spaces comes set up with the Control key as the “I’m switching screens” key. For example, press Control-↑, to move up one screen, Control-→ to move one screen to the right, and so on. Or, if you have tons of screens, you can jump to one by number (as indicated in the map shown in Figure 4-7): Control-1, Control-4, Control-9, or whatever.

You’re welcome to change these keyboard assignments, however, especially if you’re already using the Control key for other functions. Use the two bottom pop-up menus.

For example, suppose you want to switch screens by pressing the Option key rather than Control. In that case, you’d open the “To switch between Spaces” pop-up menu, press Option, and choose "

Arrow Keys.” (In these pop-up menus,

Arrow Keys.” (In these pop-up menus,  means the Option key, ⌘ is the Command key, and ^ means Control.)

means the Option key, ⌘ is the Command key, and ^ means Control.)

Tip

The pop-up menu at the bottom of the window, “To activate Spaces,” lets you choose a keystroke that opens up the master map of all your screens. (See Figure 4-9.)

Once you’ve got Spaces set up and turned on, the fun begins. Start by moving to the virtual screen you want. Here are some ways to do that:

Choose a virtual screen’s number from the Spaces menulet, shown in Figure 4-7.

Press Control-arrow key, or whatever keystroke you set up as described above. Or hold down Control and keep tapping the arrow key to scroll through all your screens.

Press Control-number key to jump to a screen without having to scroll.

Use the heads-up switcher (The New, Improved “Alt-Tab”), or the Dock, to select a program; Spaces switches to the proper screen automatically.

When you make a switch, you see a flash of animation as one screen flies away and another appears. You also see the display shown in Figure 4-8 to help you orient yourself among your magnificent array of virtual monitors.

Figure 4-8. This display appears momentarily when you switch screens. The arrow shows you the screens you’re moving to and from. You can even move diagonally. While pressing Control, press two arrow keys on your keyboard at once (like ↓ and →).

Now that you’re “on” the screen you want, open programs and arrange windows onto it as usual.

The Fn-F8 key opens up a gigantic miniature (if there is such a thing) of your entire Spaces universe (Figure 4-9).

Clicking the Spaces icon in the Dock brings up the same display.

Note

As usual, you may run into trouble with this key if you’re using Apple’s aluminum, superflat keyboard. See the box on All-Apps Exposé.

Figure 4-9. Press F8, or click Spaces in your Dock, to open this live master view of all the windows on all the screens. (The windows update in real time—if you’re in a chat or playing a movie, for example.) You can actually drag individual windows from one of these “window panes” (actually virtual screens) to another. In fact, you can even use the Exposé keystrokes to make all the windows on all the screens visible at once, for ease in moving them around the screens.

Get oriented. You could have sworn you opened your favorite Web site—where the heck is it? Pressing Fn-F8 gives you an instant readout of where all your windows are sitting at the moment.

Switch screens. Click any “pane” of the big-picture view to jump to the screen.

Reorder the screens. Using any blank background spot as a handle, you can drag the actual panes of the big-picture view around to rearrange them. If you decide that your email screen should really be at top left, drag it there.

Move windows around. Here’s the real power of the big-picture view. As shown in Figure 4-9, you can actually drag windows from one screen to another. You can use any part of the window as a handle, not just the title bar.

Hit an Exposé keystroke. You can actually use the F9 and F10 Exposé keystrokes while you’re in the Fn-F8 big-picture view.

Yes, this gets kind of meta, but it’s useful when you’re trying to arrange your windows and programs among your screens. Once you’re in the big-picture view, for example, you can hit F9 to see all windows on all screens scurry apart, so that nothing is covered up. Then start dragging windows onto different screens as necessary.

One way to move a particular window to a different screen is to drag it in big-picture view, as shown in Figure 4-9.

But there are two other ways that don’t require entering the Fn-F8 big-picture view:

Drag a window (using its title bar as a handle) all the way to the edge of the screen. Stay there with the mouse button still down. After about a second, you’ll see the adjacent screen slide into view; you’ve just moved the window.

Click anywhere inside a window, and keep the mouse button down. Now press your screen-switching keystroke (Control-←, for example, or Control-3). You’ve just moved the window to the designated screen.

To be sure, these are power-user techniques that may not come naturally. But the Fn-F8 big-picture view is always waiting should you become befuddled.

Tip

What if you want to drag something from one screen (like a photo in iPhoto) into a window that’s on a different screen (like an outgoing email message)?

Two ways; take your pick. First, you can start dragging whatever it is—and then, in mid-drag, press F8 to open the big-picture view, and complete the drag directly onto the other Space (and even into the relevant window in that Space).

Another approach: Start dragging. With the mouse still down, press ⌘-Tab to open the application switcher. Continue the drag onto the icon of the receiving program, and still keep the mouse button down. Mac OS X switches to the appropriate virtual screen automatically.

When it comes to getting windows out of your way, nothing can touch Exposé and Spaces for speed and entertainment value. Once you’ve mastered those features, the traditional rituals of hiding windows will seem charmingly quaint. “When I was your age,” long-time Mac people will tell their grandchildren, “we used to have to hold down the Option key to hide windows!”

But you know the drill at software companies: They addeth, but they never taketh away. All the old techniques are still around.

For the purposes of this discussion, when a program is hidden, all its windows, tool palettes, and button bars disappear. You can bring them back only by bringing the program to the front again (by clicking its Dock icon again, for example).

If your aim is to hide only the program you’re currently using, Mac OS X offers a whole raft of approaches to the same problem. Many of them involve the Option key, as listed here:

Option-click any visible portion of the desktop. The program you were in vanishes, along with all its windows.

Option-click any other program’s icon on the Dock. You open that program (or bring all its windows to the front) and hide all the windows of the one you were using.

Option-click any visible portion of another program’s windows. Once again, you switch programs, hiding the one you were using at the time.

From the Application menu, choose Hide iPhoto (or whatever the program is). The Application menu is the boldfaced menu that bears the program’s name.

When you’ve highlighted a Dock icon by pressing ⌘-Tab to rotate through the running programs, press the letter H key. The program hides itself instantly. Leave the ⌘ key down the whole time, and after pressing the H, press Tab again to move on to the next program. If you release the keys while “stopped” on the program instead, you’ll bring it forward rather than hiding it.

Press ⌘-H. This may be the easiest and most useful trick of all (although it doesn’t work in every program). Doing so hides the program you’re in; you then “fall down” into the next running program.

To unhide a program and its windows, click its Dock icon again, choose the Show All command in the Application menu, or press ⌘-Tab to summon the heads-up application display.

In Mac OS X, there’s more to managing your window clutter than simply hiding entire programs. You can also hide or show individual windows of a single program. In fact, Apple must believe that hiding a window will become one of your favorite activities, because it offers at least four ways to do so:

Choose Window→Minimize Window, if your program offers such a command, or press ⌘-M.

Click the Minimize button on the window’s title bar, as shown in Figure 4-10.

Double-click the window’s title bar.

In any case, the affected window shrinks down until it becomes a new icon in the right side of the Dock. Click that icon to bring the window back.

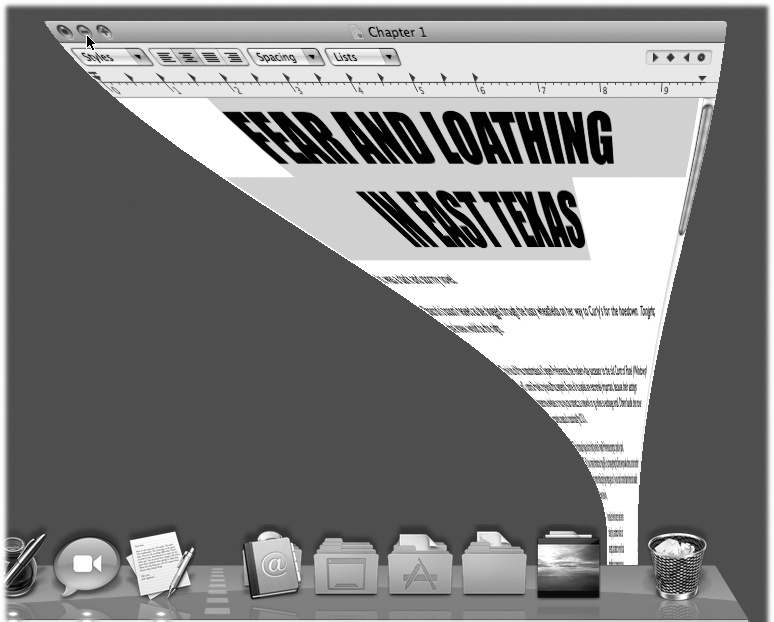

Every operating system needs a mechanism to associate documents with the applications that created them. When you double-click a Microsoft Word document icon, for example, it’s clear that you want Microsoft Word to launch and open the document.

So how does Mac OS X know how to find a document’s mommy?

It actually has two different mechanisms.

Filename extensions. A filename extension is a suffix following a period in the file’s name, as in Letter to Mom.doc. (It’s usually three letters long, but doesn’t have to be.) These play a role in determining which documents open into which programs.

That’s how Windows identifies its documents, too. If you double-click something called memo.doc, it opens in Microsoft Word. If you double-click memo.wri, it opens in Microsoft Write, and so on.

Note

Mac OS X comes set to hide most filename extensions, on the premise that they make the operating system look more technical and threatening. If you’d like to see them, however, choose Finder→Preferences, click the Advanced button, and then turn on “Show all file extensions.” Now examine a few of your documents; you’ll see that their names now display the previously hidden suffixes.

Figure 4-10. When you click the center button on a window title bar, double-click the title bar, or press ⌘-M, you minimize that window, getting it out of your way and off your screen. Minimizing on the Mac is a lot like minimizing in Windows; the minimized window is now represented by an icon on your Dock, which you can click to reopen the window.

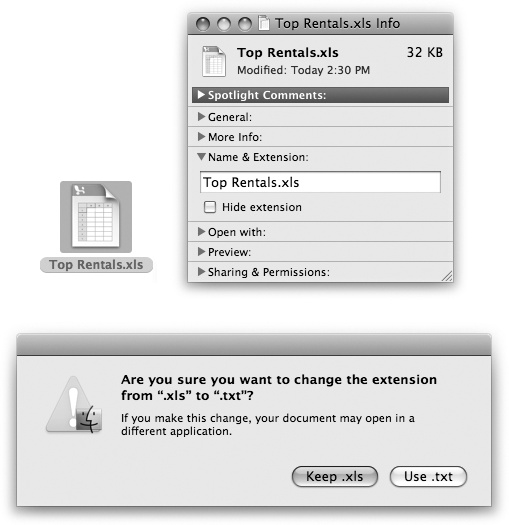

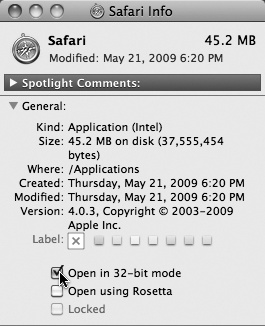

You can hide or show these suffixes on an icon-at-a-time basis, too (or a clump-at-a-time basis). Just highlight the icon or icons you want to affect, and then choose File→Get Info. In the resulting Info window, proceed as shown in Figure 4-11.

Your preferences. If you’ve used the “Always Open with” command to specify which program opens your document (described next), that’s the one that opens; this preference overrides the filename extension system. Snow Leopard memorizes that new pairing in an internal Unix database. (If you’re a Unix geek, you can actually open and inspect that database.)

It’s possible to live a long and happy life without knowing anything about these suffixes and relationships. Indeed, the vast majority of Mac fans may never even encounter them. But if you’re prepared for a little bit of technical bushwhacking, you may discover that understanding document-program relationships can be useful in troubleshooting, keeping your files private, and appreciating how Mac OS X works.

Filename extensions don’t know which parent program should open a particular document. Suppose you’ve downloaded a graphic called Sunset.jpg. Well, almost any program these days can open a JPEG graphic—Photoshop, Word, Preview, Safari, and so on. How does Mac OS X know which of these programs to open when you double-click the file?

Figure 4-11. Top: In the Info window, open the Name & Extension pane. Now you can see what Mac OS X really thinks your file is called. Turn “Hide extension” on if you’d rather not see the file name suffix in the Finder. Bottom: If you try to add a suffix of your own, Mac OS X objects, in effect saying, “Hey—I’ve already got a filename extension for this, even if you can’t see it. Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” (And you can turn off this warning, if you like. Choose Finder→Preferences→Advanced pane. Turn off “Show warning before changing an extension.”)

Fortunately, you can decide. You can reassign a document (or all documents of its kind) to a specific program. Here’s the rundown.

Double-clicking a graphics file generally opens it in Preview, the graphics viewer included with Mac OS X. Most of the time, that’s a perfectly good arrangement. But Preview has only limited editing powers. What if you decide to edit a graphics file more substantially? You’d want it to open, just this once, into a different program—Photoshop Elements, for example.

To do so, you must access the Open With command. You can find it in two places:

Highlight the icon, and then choose File→Open With.

Right-click the file’s icon. Or, in a Finder window, highlight the icon and then open the

menu. In the shortcut menu, choose Open With.

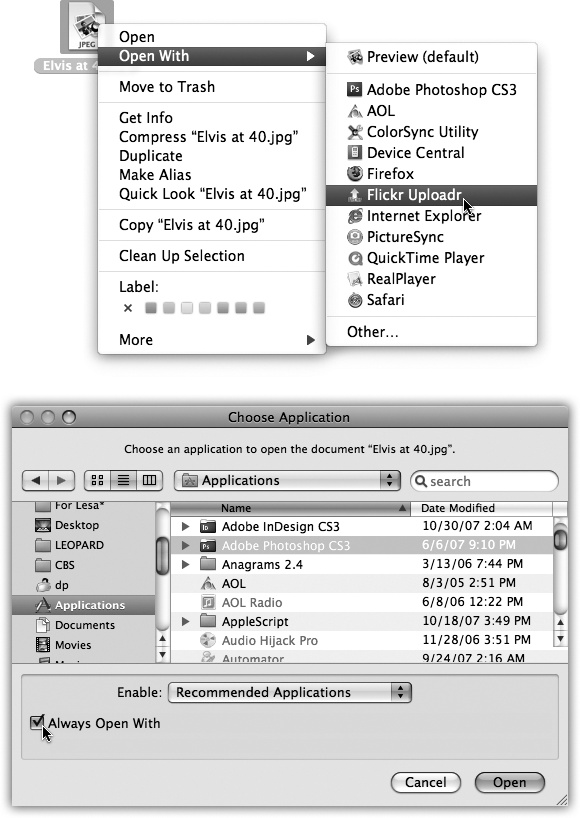

menu. In the shortcut menu, choose Open With.Study the submenu for a moment (Figure 4-12, top). The program whose name says “(default)” indicates which program usually opens this kind of document.

Figure 4-12. Top: The shortcut menu offers a list of programs capable of opening an icon. If you were to press the Option key right now, the words Open With would suddenly change to say Always Open With. Bottom: If you choose Other, you’re prompted to choose a different program. Turn on Always Open With if you’ll always want this document to open in the new parent program. Otherwise, this is a one-time reassignment.

From this pop-up menu, choose the name of the program you’d rather open this particular file, right now, just this once.

After opening a TIFF file in, say, Photoshop Elements for editing, you haven’t really made any changes in the fabric of your Mac universe. The next time you double-click that file, it opens once again in Preview.

If you wish this particular file would always open in Photoshop Elements, the steps are slightly different. In fact, there are three different ways:

In the Choose an Application dialog box (the one that appears when you double-click a document whose “parent” program isn’t clear), turn on “Always Open With” (shown at bottom in Figure 4-12).

Start out with one of the previously described techniques (File→Open With, or Control-click/right-click the file’s icon and choose Open With)—but after you see the menu, press the Option key, too. Before your very eyes, the Open With command changes to say Always Open With.

Highlight the icon, and then choose File→Get Info. Open the “Open with” panel. Choose a new “parent” program’s name from the pop-up menu. You’ll see that the word “(default)” changes position, now tacking itself onto the name of the program you’ve chosen.

So much for reassigning one document (or a group of documents) at a time. What if you’re writing, say, a book about Mac OS X, and you’ve been taking a lot of screenshots? Mac OS X saves each captured screen illustration as a graphics file in something called PNG format. That’s all fine, except that every time you double-click one of these, it opens into Preview, where you can’t paint out unwanted details.

You could reassign all these files, one at a time, to a different program, but your grandchildren would have grandchildren by the time you finish. In this case, you want to tell Mac OS X, “For heaven’s sake, make all PNG files open in Photoshop from now on!”

To make it happen, start by highlighting any PNG file. Choose File→Get Info. (The shortcut menus won’t help you in this case.) Open the “Open with” panel.

From its pop-up menu, choose the program you want to open this kind of document from now on. (If the one you prefer isn’t listed, use the Other option, which opens the Choose an Application dialog box so you can navigate to the one you want. Find and double-click the program.)

This time, follow up by clicking Change All beneath the pop-up menu. (This button is dimmed until you’ve actually selected a different program from the pop-up menu.) Mac OS X asks you to confirm by clicking Continue or pressing Return.

From now on, double-clicking any similar kind of document opens it in the newly selected program.

In Windows, of course, you can operate every menu in every program from the keyboard—and every control in every dialog box—thanks to the power of the Alt key.

Mac OS X offers full keyboard control, too. You can operate every control in every dialog box from the keyboard, including pop-up menus and checkboxes. And you can even redefine many of the keyboard shortcuts in Mac OS X and even your programs. In short, if you were a keyboard power-user in Windows, you’ll feel right at home in Mac OS X.

Here are some of the ways you can control your Mac mouselessly. In the following descriptions, you’ll encounter the factory settings for the keystrokes that do the magic—but as you’ll see in a moment, you can change these key combos to anything you like. (The System Preferences→Keyboard→Keyboard Shortcuts tab contains the on/off switches for these features.)

Note

On modern-day, aluminum keyboards, the keystrokes described below may not work unless you also press the Fn key simultaneously.

If that seems just a tad clumsy, you can eliminate the Fn-key requirement either by using the “Use all F1, F2, etc. keys as standard function keys” option described on The Complicated Story of the Function Keys—or by choosing a different keystroke altogether (Changing a Menu Keyboard Shortcut).

When you press Control-F2, the ![]() menu is highlighted. At this point, you can “walk” to another menu by pressing the ← or → keys (or Tab and Shift-Tab). When you reach the menu you want, open it by pressing ↓, space, Return, or Enter.

menu is highlighted. At this point, you can “walk” to another menu by pressing the ← or → keys (or Tab and Shift-Tab). When you reach the menu you want, open it by pressing ↓, space, Return, or Enter.

Walk down the commands in the menu by pressing ↑, or ↓, or jump directly to a command in the menu by typing the first couple of letters of its name. Finally, “click” a menu command by pressing Enter, Return, or the space bar.

You can also close the menu without making a selection by pressing Esc or ⌘-period.

Once you’ve pressed Control-F3, you can highlight any icon on the Dock by pressing the appropriate arrow keys (or, once again, Tab and Shift-Tab).

Then, once you’ve highlighted a Dock icon, you “click it” by pressing Return or the space bar. Again, if you change your mind, press Esc or ⌘-period.

Every time you press Control-F4, you bring the next window forward, eventually cycling through every window in every open program. Add the Shift key to cycle through them in the opposite order.

You may remember that Mac OS X offers a different keystroke for cycling through the different windows in your current program (it’s ⌘-~, the tilde symbol at the upper left of your keyboard). Control-F4, on the other hand, tours all windows in all programs. Both keystrokes are useful in different situations.

This one is on the unpredictable side, but it more or less works in most programs that display a Mac OS X–style toolbar: the Finder, System Preferences, and so on.

When you press Control-F5, you highlight the first button on that toolbar. Move the “focus” by pressing the arrow keys or Tab and Shift-Tab. Then tap Return or the space bar to “click” the highlighted button.

In a few programs that feature floating tool palettes, you can highlight the frontmost palette by pressing Control-F6. At this point, use the arrow keys to highlight the various buttons on the palette. You can see the effect when, for example, you’re editing text in TextEdit and you’ve also opened the Font palette. Pressing Control-F6 highlights the Font palette, taking the “focus” off your document.

You can even operate menulets—those menu-bar status indicators for your speaker volume, wireless networks, and so on—from the keyboard.

This time, the trick is to hit Control-F8. That highlights the leftmost Apple menulet. Now you can use your ← and → arrow keys to move around the menu bar; when you’ve highlighted the one you want, press Return or the space bar to “click” that menu and open it.

You can also navigate and manipulate any dialog box from the keyboard.

See the dialog box shown in Figure 4-13 If you turn on “All controls” at the bottom, then pressing the Tab key highlights the next control of any type, whatever it may be—radio button, pop-up menu, and so on. Press the space bar to “click” a button or open a pop-up menu. Once a menu is open, use the arrow keys (or type letter keys) to highlight commands on it, and the space bar to “click” your choice.

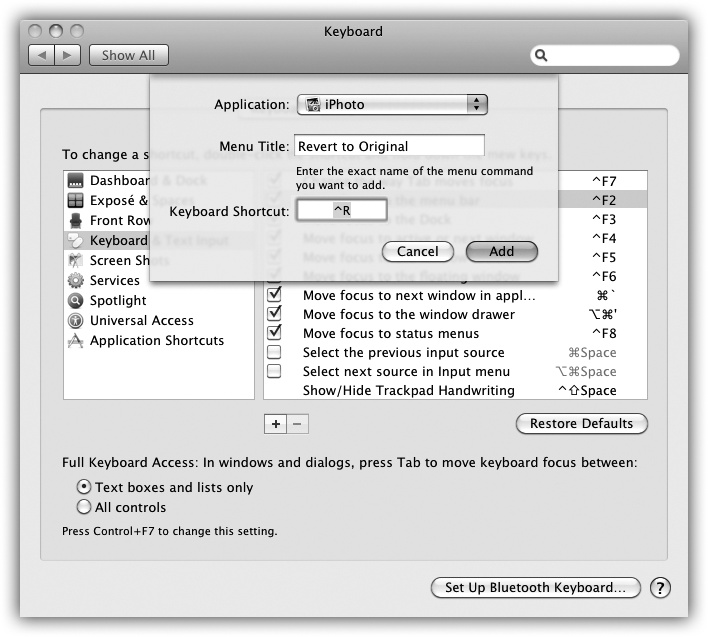

Suppose you love iPhoto (and who doesn’t?) but one thing drives you crazy: The Revert to Original command, which discards all the changes you’ve ever made since taking the photo, has no keyboard equivalent. You must trek up to the menu bar every time you need that command.

Figure 4-13. If you choose All Applications from the top pop-up menu, you can change the keyboard combo for a certain command wherever it appears. You could, for example, change the keystroke for Page Setup in every program at once. (Beware the tiny yellow triangles; they let you know if a chosen keystroke conflicts with another Mac OS X keystroke.)

This is why Mac OS X lets you add keyboard shortcuts to menu commands that lack them—or change the command in programs whose key assignments break with tradition. (It works in any program that uses the standard Mac OS X menu software, which rules out Microsoft Word and the other Office programs.) Here’s the routine:

Choose

→System Preferences→Keyboard. Click the Keyboard Shortcuts tab.

→System Preferences→Keyboard. Click the Keyboard Shortcuts tab.You’re shown a list of all of Mac OS X’s built-in keyboard assignments.

Click the + button just beneath the list.

The dialog box shown in Figure 4-13 appears.

Indicate which program needs behavior modification.

In this example, you’d choose iPhoto from the Application pop-up menu. (If the program’s name doesn’t appear in the pop-up menu, choose Other; navigate to, and double-click, the program you want.)

Carefully type in the name of the menu command whose keyboard shortcut you want to change or add.

Type it exactly as it appears in the menu, complete with capitalization and the little ellipsis (…) that may follow it. (You make the ellipsis character by pressing Option-semicolon.)

Click in the Keyboard Shortcut box. Press the new or revised key combo you want.

For example, press Control-R for iPhoto’s Revert to Original command. You’ll see the Mac’s notation of your keystroke appear in the Keyboard Shortcut box—unless, of course, the combo you selected is already in use within that program. In that case, you hear only an error sound that means “Try again.”

Click Add.

The dialog box closes. By scrolling down in your Keyboard Shortcuts list, you’ll see that the keystroke you selected has now been written down for posterity under the appropriate program’s flippy triangle. (To get rid of it, click its name and then click the - button beneath the list.)

The next time you open the program you edited, you’ll see that the new keystroke is in place.

Tip

To delete or change one of your custom menu shortcuts, open System Preferences→Keyboard→Keyboard Shortcuts. Click Application Shortcuts in the list at left. Click the command you’d like to edit. Press Delete to get rid of it; or, to try a different key combo, click where the existing keyboard shortcut appears, and then press a new one.

As you’ve no doubt become painfully aware, there are hundreds of keyboard combinations for the various Mac OS X functions and settings. That’s good, because keyboard shortcuts are efficient and quicker than using the mouse. But that’s also bad, because there’s no way you’ll be able to remember all of them—and some of most useful shortcuts are ridiculous, multikey affairs that you’ll never remember at all.

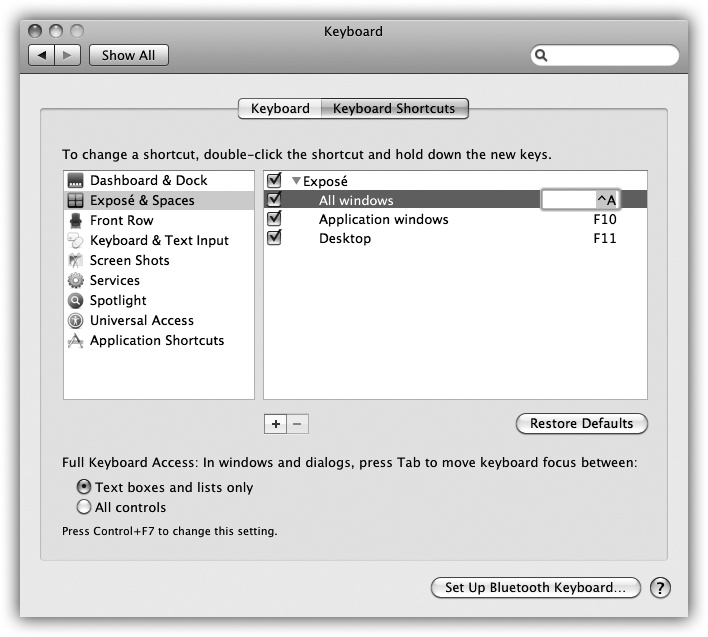

Snow Leopard comes with a keyboard-shortcut center, shown in Figure 4-14. Here, you can look over all of the common Mac OS X hidden keyboard functions—for Exposé, Spotlight, Spaces, the Dashboard, the Dock, and many others—and change them.

Here’s how it goes:

Choose

→System Preferences. Click Keyboard. Click the Keyboard Shortcuts tab.

→System Preferences. Click Keyboard. Click the Keyboard Shortcuts tab.You arrive at the dialog box shown in Figure 4-14.

In the left-side list, click the category or function you want.

Your choices include Dashboard & Dock, Exposé & Spaces, Front Row, Keyboard & Text Input, and so on. When you click a category name, you see the available keyboard shortcuts.

Tip

You don’t have to be content with changing one of these keyboard shortcuts. You can also turn it off by clicking the corresponding checkbox. That’s great if one of Apple’s predefined keystrokes—for a function you don’t even use—is interfering with one in a program you like.

Figure 4-14. The keyboard shortcut center in Snow Leopard lets you redefine the keystrokes that trigger many basic Mac OS X features, menu commands in your programs, and software you’ve built yourself using Automator (Address Book).

Click the command you want to change. Then click the current keyboard combination.

Suppose, for example, that you wished that the All-Apps Exposé keystroke were something easier to remember, like Control-A. So in step 2, you’d click Exposé & Spaces. In this step, you’d click “All windows,” as shown in Figure 4-14. Then you’d click where it currently says F9.

Press a new key combination.

In this example, you’d press Control-A.

Be careful, though. Mac OS X keystrokes take precedence over all others. So if you choose a keystroke like ⌘-P for something, well, by golly, you’ll no longer be able to use ⌘-P to print anything in any of your programs. Think before you assign. Run a couple of tests afterward.

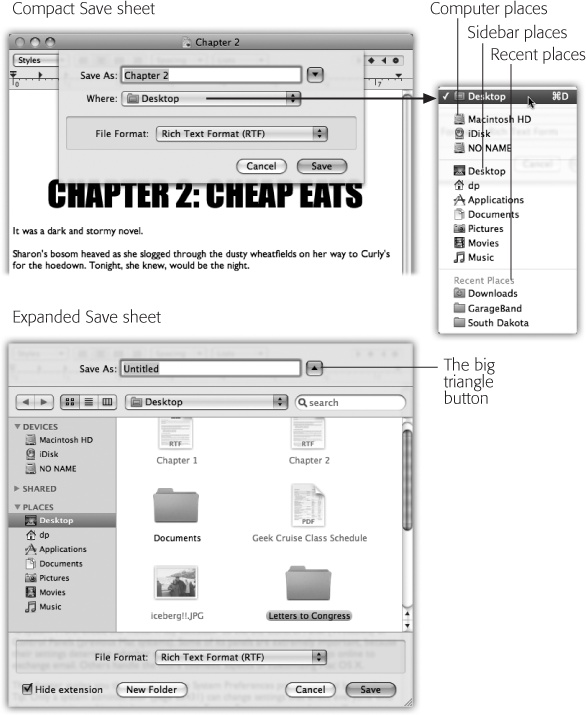

When you choose File→Save, you’re asked where you want the new document stored on your hard drive. The resulting dialog box is crystal-clear—more than ever, it’s a miniature Finder. All the skills you’ve picked up working at the desktop come into play here.

To give it a try, launch any Mac OS X program that has a Save or Export command—TextEdit, for example. Type a couple of words, and then choose File→Save. The Save sheet appears (Figure 4-15).

Tip

In Mac OS X, a quick glance at the Close button in the upper-left corner of a document window tells you whether it’s been saved. When a small dot appears in the red button, it means you’ve made changes to the document that you haven’t saved yet. (Time to press ⌘-S!). The dot disappears as soon as you save your work.

In the days of operating systems gone by, the Save dialog box appeared dead center on the screen, where it commandeered your entire operation. Moreover, because it seemed stuck to your screen rather than to a particular document, you couldn’t actually tell which document you were saving—a real problem when you quit out of a program that had three unsaved documents open.

In most Mac OS X programs, there’s no mystery regarding which document you’re saving, because a little Save dialog box called a sheet slides directly out of the document’s title bar. Now there’s no mistaking which document you’re saving.

Better still, this little Save box is a sticky note attached to the document. It stays there, neatly attached and waiting, even if you switch to another program, another document, the desktop, or wherever. When you finally return to the document, the Save sheet is still there, waiting for you to type a file name and save the document.

Of course, you, O savvy reader, have probably never saved a document into some deeply nested folder by accident, never to see it again. But millions of novices (and even a few experts) have fallen into this trap.

When the Save sheet appears, however, a pop-up menu shows you precisely where Mac OS X proposes putting your newly created document: usually in the Documents folder of your own Home folder. For many people, this is an excellent suggestion. If you keep everything in your Documents folder, it will be extremely easy to find, and you’ll be able to back up your work just by dragging that single folder to a backup disk. As shown at top in Figure 4-15, the Where pop-up menu gives you direct access to some other places you might want to save a newly created file. (The keystrokes for the most important folders work here, too—Shift-⌘-H for your Home folder, for example.)

Figure 4-15. Top: The Save dialog box, or sheet, often appears in its compact form. Right (inset): If you open the Where pop-up menu, you’ll find that Mac OS X lists all the places it thinks you might want to save your new document: on the hard drive or iDisk, in a folder you’ve put into your Sidebar (Zoom Button), or into a folder you’ve recently opened. Bottom: If you want to choose a different folder or create a new folder, click the ▼ button shown above to expand the dialog box. Here, you see the equivalent of the Finder—with a choice of icon, list, or column view. Even the Sidebar is here, complete with access to other disks on the network. Supertip: Even in the Save or Open dialog box, you can highlight an icon (or several) and then press ⌘-I. You switch back to the Finder, where the Get Info box is waiting with the date, size, and other details about the selected icons.

In any case, when you save a file, the options in the Where pop-up menu have you covered 90 percent of the time. Most people work with a limited set of folders for active documents.

But when you want to save a new document into a new folder, or when you want to navigate to a folder that isn’t listed in the Where pop-up menu, all is not lost. Click the ▼ button identified in Figure 4-15. The Save sheet expands miraculously into a very familiar sight: a miniature version of the Finder.

There’s your Sidebar, complete with access to the other computers on your network. There’s the Back button. There’s your toggle switch between views; in Snow Leopard, you can even switch to icon view here, in addition to the traditional list and column views.

Tip

In column view, your first instinct should be to widen this window, making more columns available. Do so by carefully dragging the lower-right corner of the dialog box. Mac OS X remembers the size you like for this Save sheet independently in each program.

Most of the familiar Finder-navigation shortcuts work here, too. For example, press the right and left arrow keys to navigate the columns, or the up and down arrow keys to highlight the disk and folder names within a column. Once you’ve highlighted a column, you can also type to select the first letters of disk or folder names.

Highlight the name of the folder in which you want to save your newly created document. Alternatively, you can click the New Folder button to create a new folder inside whatever folder is highlighted in the column view. (The usual New Folder keystroke works here, too: Shift-⌘-N.) You’ll be asked to type the new name for the folder. After you’ve done so, click Create (or press Return). The new folder appears in the rightmost pane of the column view. You can now proceed with saving your new document into it, if you like.

The next time you save a new document, the Save sheet reappears in whatever condition you left it. That is, if you used column view the last time, it’s still in column view. At any time, you can collapse it into simplified view, shown at top in Figure 4-15, by clicking the ▴ button to the right of the Where pop-up menu.

Tip

The Save box always displays whatever places you’ve put in your Sidebar. (In compact view, the Where pop-up menu lists them; in expanded view, you see the Sidebar itself.)

The bottom line: If, on some project, you find yourself wanting to save new documents into the same deeply buried folder all the time, press F11 to duck back to the Finder, and add it to your Sidebar. From now on, you’ll have quick access to it from the Save dialog box.

The Search bar at the top of the Open and Save dialog box is a clone of the Finder’s Search bar (Chapter 3). Press ⌘-F to make your insertion point jump there. Type a few letters of the name of the file or folder you’re looking for, and up it pops, regardless of its actual hard-disk location.

Your savings: five minutes of burrowing through folders to find it, and several pages of reading about how to navigate the Save and Open boxes.

The Save dialog box in many programs offers a pop-up menu of file formats below the Save As box. Use this menu when preparing a document for use by somebody else—somebody whose computer doesn’t have the same software. For example, if you’ve used a graphics program to prepare a photograph for use on the Web, this menu is where you specify JPEG format (the standard Web format for photos).

The dialog box that appears when you choose File→Open is almost identical to the expanded Save File sheet. Because you encounter it only when you’re opening an existing file, this dialog box lacks the Save button, file name field, and so on.

Note

Furthermore, the Open dialog box shows you only icons for disks, folders, and documents that you can actually open at this moment. For example, when you’re using GarageBand, picture files show up dimmed.

But it does have a new Sidebar category called Media, which gives you direct access to all your photos, music, and movies. The premise is that Apple figures you might want to import these items into a document you’re working on.

Most of the other Save File dialog box controls, however, are equally useful here. That handy Spotlight search bar is still there, only a ⌘-F away. Once again, you can begin your navigation by seeing what’s on the desktop (press ⌘-D) or in your Home folder (press Shift-⌘-H). Once again, you can find a folder or disk by beginning your quest with the Sidebar, and then navigate using either list or column view. And once again, you can drag a folder, disk, or file icon off your desktop directly into the dialog box to specify where you want to look. (If you drag a file icon, you’re shown the folder that contains it.)

When you’ve finally located the file you want to open, do so by double-clicking it or highlighting it (which you can do from the keyboard), and then pressing Return, Enter, or ⌘-O.

In general, most people don’t encounter the Open File dialog box nearly as often as the Save File dialog box. That’s because the Mac offers many more convenient ways to open a file—double-clicking its icon in the Finder, choosing its name from the ![]() →Recent Items command, and so on—but only a single way to save a new file.

→Recent Items command, and so on—but only a single way to save a new file.

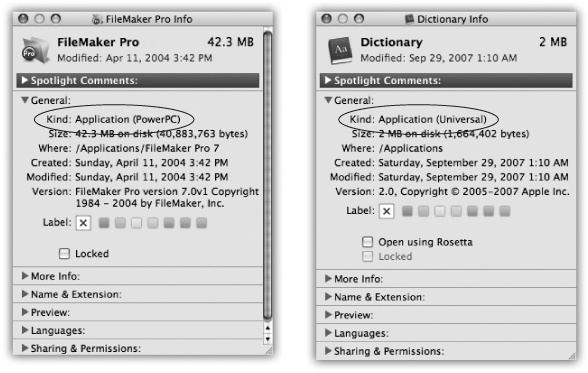

By the end of 2006, Apple had abandoned the PowerPC processors (made by IBM and Motorola) that had been in Macs since the beginning. It switched its entire Macintosh product line over to Intel’s Core Duo processors (the successor to the Pentium).

Yes, that Intel. The company that Mac partisans had derided for years as part of the Dark Side. The company that Steve Jobs routinely belittled in his demonstrations of PowerPC chips. The company whose marketing mascot Apple lit on fire in a 1996 attack ad on TV.

Why the change? Apple’s computers can only be as fast as the chips inside them, and the chips that IBM had in the works just weren’t keeping up with the industry. As one editorial put it, “Apple’s doing a U-turn out of a dead-end road.”

And sure enough, Intel-based Macs start up and run much faster than the old Macs, thanks to the endless march of speed improvements in the chip-making world. And thanks to that Intel chip, today’s Macs can even run Microsoft Windows and all of the thousands of Windows programs. (Chapter 8 has details.)

At the time, though, there was a small glitch: Existing Mac software didn’t run on Intel chips.

Apple would have to ask the world’s software companies to rewrite their programs yet again, after already having dragged them through the Mac OS 9-to-Mac OS X transition only a few years earlier.

Fortunately, the transition wasn’t as gruesome as you might expect. First, Apple had already secretly recompiled (reworked) Mac OS X itself to run on Intel chips.

Furthermore, Apple wrote an invisible translation program, code-named Rosetta, which permits the existing library of Mac OS X programs—Photoshop, Word, and so on—to run, unmodified, on Intel Macs.

Note

When you install Snow Leopard, as described in Appendix A, you have the option to install Rosetta, so you’ll have it just in case you want to run a pre-Intel program. (All software that’s still on the market has long since been updated to the so-called Universal versions—that is, Intel-compatible. But plenty of older programs, long since abandoned, or whose software companies have gone under, are still around.)

But if it’s too late to install Rosetta along with Snow Leopard, or if you bought a new Mac with Snow Leopard already installed, don’t worry. When the day comes that you try to run a pre-Intel program, Snow Leopard offers to grab Rosetta for you. It says: “To open BeeKeeper Pro, you need to install Rosetta. Would you like to install it now?” When you click Install, Snow Leopard downloads it for you automatically.

They do not, however, run especially fast on Intel Macs. In fact, many of them run slower than they did on pre-Intel Macs.

To make their programs perform at full speed on Intel-based Macs, programmers have to update their wares. All the big software companies promised to make their programs into universal binaries—programs that run equally well on PowerPC- and Intel-based Macs with a double-click on the very same Finder icon.

Figure 4-16. Here’s a quick way to tell if a program is an old one that will run slowly on an Intel Mac (instead of a Universal or Intel one that won’t require the Rosetta software translation). Highlight its icon and choose File→Get Info. Near the top, you see either “Application: PowerPC” (old and slow), “Application: Intel” (runs only on Intel Macs), or “Application: Universal” (runs fast on both Intel and PowerPC machines).

It took two years for all the big-name programs to fall in line, but they finally did. Photoshop, Microsoft Office, Final Cut Pro, QuarkXPress, FileMaker, Firefox…one by one, the world’s most popular Mac programs were reworked into Universal versions. (There’s even a list of them—over 7,000 so far—at www.apple.com/universal/.)

You have only two indications that you’re using a program originally designed for PowerPC-based Macs: First, you’ll see a notation in the program’s Get Info window (see Figure 4-16). Second, you’ll probably discover that the program isn’t as fast as it used to be.

If all this talk about architectures and chips makes your brain hurt, you can at least take comfort in one fact: No matter which kind of Mac you’ve got Snow Leopard installed on, every feature, tip, and trick you’ve learned from this book will work exactly the same.

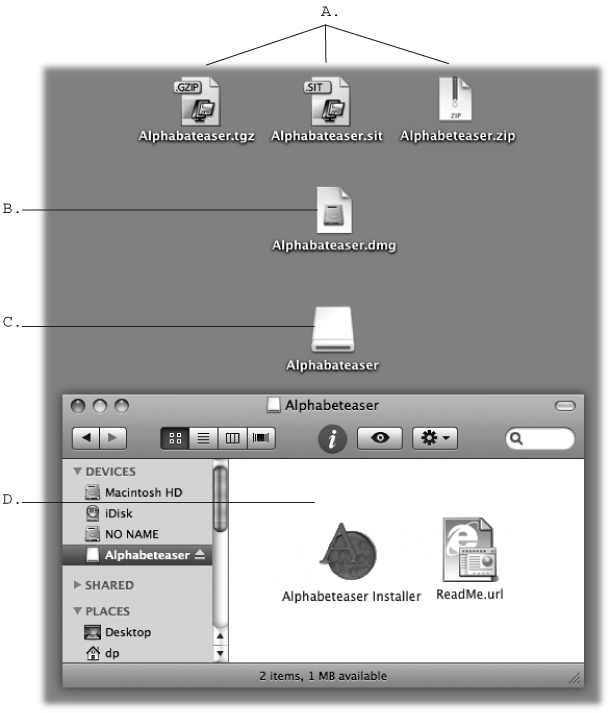

In general, new programs arrive on your Mac via one of two avenues: on a CD or DVD, or via an Internet download. The CD method is slightly simpler; see Performing the Installation later in this section.

For help installing downloaded programs, on the other hand, read on.

Programs you download from the Internet generally arrive in a specially encoded, compressed form. (And unless you’ve changed the settings, they arrive in the Downloads folder stack on your Dock.)

The downloaded file’s name usually has one of these filename extensions:

.sit indicates a StuffIt file, the standard Macintosh file-compression format of years gone by.

.zip is the standard Windows compression file format. And because Snow Leopard has a built-in Compress command right in the File menu (and doesn’t come with StuffIt Expander), .zip is the new standard Macintosh compression format. It certainly makes life easier for people who have to exchange files with the Windows crowd.

.tar is short for tape archive, an ancient Unix utility that combines (but doesn’t compress) several files into a single icon, for simplicity in sending.

.gz is short for gzip, a standard Unix compression format.

.tar.gz or .tgz represents one compressed archive containing several files.

.dmg is a disk image, described below.

Fortunately, if you use Safari (Chapter 12) as your Web browser, you don’t have to worry about all this, because it automatically unzips and unstuffs them.

If you use some other browser, StuffIt Expander can turn all of them back into usable form when you download a file. (StuffIt Expander doesn’t come with Mac OS X, but you can download it for free from, for example, this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.)

Once you’ve unzipped a downloaded program, it often takes the form of a disk image file, whose name ends with the letters .dmg (second from top in Figure 4-17). Some files arrive as disk images straight from the Web, too, without having been compressed first.

Disk images are extremely common in Mac OS X. All you have to do is double-click the .dmg icon. After a moment, it magically turns into a disk icon on your desktop, which you can work with just as though it’s a real disk (third from top in Figure 4-17). For example:

Double-click it to open it. The software you downloaded is inside.

Remove it from your desktop by dragging it to the Trash (whose icon turns into a big silver Eject key as you drag), highlighting it and pressing ⌘-E (the shortcut for File→Eject), clicking its

button in the Sidebar, or right-clicking it, and then choosing Eject from the shortcut menu. (You’ve still got the original .dmg file you downloaded, so you’re not really saying goodbye to the disk image forever.)

button in the Sidebar, or right-clicking it, and then choosing Eject from the shortcut menu. (You’ve still got the original .dmg file you downloaded, so you’re not really saying goodbye to the disk image forever.)

When you’ve finished unzipping or unstuffing a downloaded file, you may have several icons on your desktop or in the Downloads folder. Some are useful; some you’re free to trash:

The original compressed file. It’s safe to throw away the .sit, .tar, .gz, or .tgz file you originally downloaded (after it’s decompressed, of course).

The .dmg file. Once you’ve turned it into an actual disk-drive icon, installed the software from it, and “ejected” the disk-drive icon, you can delete the .dmg file. Keep it only if you think you might need to reinstall the software someday.

The disk image itself. This final icon, the one that contains the actual software or its installer (third from top in Figure 4-17), doesn’t exist as a file on your hard drive. It’s a phantom drive, held in memory, that will go away by itself when you log out. So after installing its software, feel free to drag it to the Trash (or highlight it and press ⌘-E to “eject” it).

Working with .tar, .gz, and .dmg files are all skills unique to downloading Mac OS X programs from the Internet. Installing software from a CD or DVD is much more straightforward.

Figure 4-17. Downloading a program may strew your desktop or Downloads folder with icons. A: These are the original downloaded files. Delete them after they’re decompressed. B: The compressed file turns into this .dmg file. Double-click it to “mount” the disk image (if it didn’t appear automatically). C: And now, the disk image itself. Double-click it to open the software installer window. Eject it after the installation is complete. D: Here’s the actual software installer window. Drag the software’s icon to your Applications folder, or double-click the installer, if you see one here. After the installation is complete, you can delete all of this stuff (except maybe the .dmg file, if you think you might want to install the software again later).

In either case, once you’ve got a disk icon on your desktop (either a pseudo-disk from a disk image or a CD or DVD you’ve inserted), you’re ready to install the software. You can install many Mac OS X programs just by dragging their icons or folders to your hard drive (usually the Applications folder). Others offer a traditional installer program that requires you to double-click, read and accept a license agreement, and so on.

In both cases, where you decide to install the new program is suddenly a big issue. You have two alternatives:

In the Applications folder. Most programs, of course, sit in your Applications folder. Most of the time, this is where you’ll want to install new programs. Putting them in the Applications folder makes them available to anyone who uses the Mac.

Note

You can’t put anything in your Applications folder unless you have an Administrator account, as described on Creating an Account.

In your Home folder. Suppose you share your Mac with other people, as described in Chapter 13. If that’s your situation, you may occasionally want to install a program privately, reserving it for your own use only. In that case, just install or drag it into your Home folder, or a folder inside it. When other people log onto the machine, they won’t even know you’ve installed that new program, since it doesn’t show up in the Applications folder.

If you don’t have an Administrator account, in fact, this is your only option for installing new programs.

In Mac OS X, there’s generally no Uninstall program, and no Add/Remove Programs window. To uninstall a program, you just drag it (or its folder) from the Applications folder (or wherever it is) to the Trash.

Some programs also leave harmless scraps of themselves behind; to check for them, look for preference files or folders bearing the dearly departed program’s name in your Library folders (especially in Application Support) and your Home→Library→Preferences folder.

The essence of using most operating systems is running programs, which often produce documents.

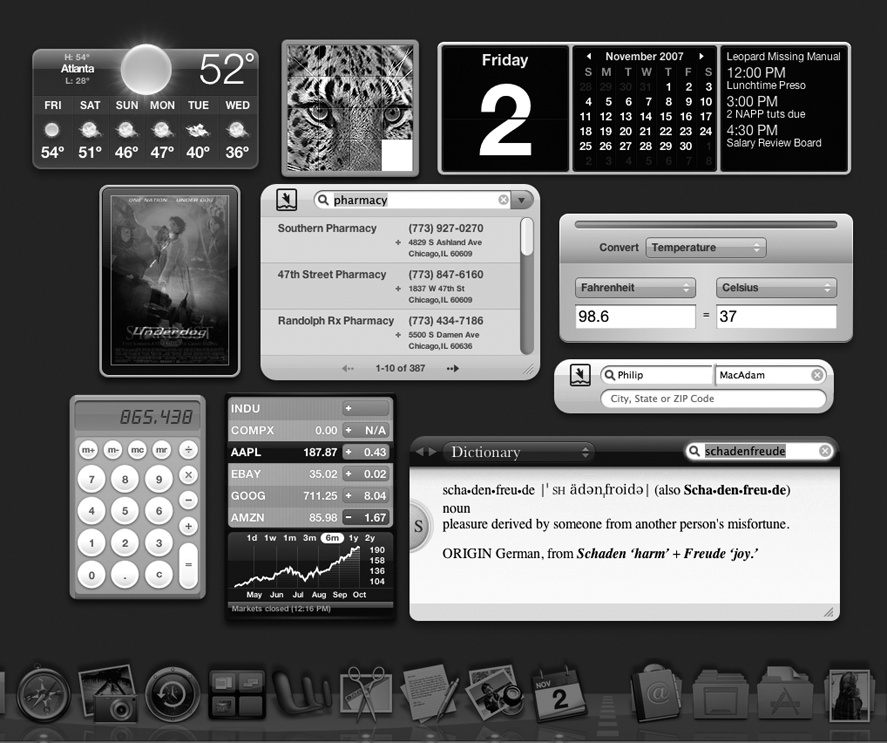

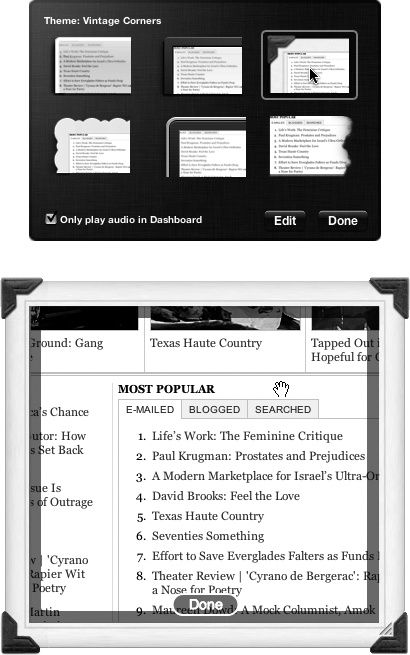

In Mac OS X, however, there’s a third category: a set of weird, hybrid entities that Apple calls widgets. They appear, all at once, floating in front of your other windows, when you press the F4 (![]() ) key. Welcome to the Dashboard (Figure 4-18).

) key. Welcome to the Dashboard (Figure 4-18).

Note

The keystroke is F4 if you have a current Apple keyboard—the thin aluminum one on a laptop or desktop Mac. In fact, you can see a tiny Dashboard logo ![]() painted right on the key.

painted right on the key.

On older, plastic keyboards, the keystroke is usually F12. Or, on laptops where F12 is the ![]() key, you have to hold down the Fn key (lower-left corner).

key, you have to hold down the Fn key (lower-left corner).

In either case, you can change the Dashboard keystroke to whatever you like, as described below.

What are these weird, hybrid entities, anyway? They’re not really programs. What they most resemble, actually, is little Web pages. They’re meant to display information, much of it from the Internet, and they’re written using Web programming languages like HTML and JavaScript.

Mastering the basics of Dashboard won’t take you long at all:

To move a widget, drag it around the screen. (Click anywhere but on a button, menu, or text box.)

To close a widget, press the Option key as you move the mouse across the widget’s face. You’ll see the

button appear at the widget’s top-left corner; click it.

button appear at the widget’s top-left corner; click it.Tip

If the Widget bar is open (as described below), every widget displays its

close button. You don’t need the Option key.

close button. You don’t need the Option key.Figure 4-18. When you summon the Dashboard, you get a fleet of floating miniprograms that convey or convert all kinds of useful information. They appear and disappear all at once, on a tinted translucent sheet that floats in front of all your other windows. You get rid of Dashboard either by pressing the same key again (F12 or whatever) or by clicking anywhere on the screen except on a widget.

To open a closed widget, click the

button at the bottom of the screen. Now the entire screen image slides upward by about an inch to make room for the Widget bar: a “perforated metal” tray containing the full array of widgets, even the ones that aren’t currently on the screen (Figure 4-19). Open one by clicking its icon.

button at the bottom of the screen. Now the entire screen image slides upward by about an inch to make room for the Widget bar: a “perforated metal” tray containing the full array of widgets, even the ones that aren’t currently on the screen (Figure 4-19). Open one by clicking its icon.

On Macs with newish graphics cards, a new widget appears by splashing down into the center of your screen, sending realistic pond ripples across the liquidy glass of your screen. These widgets really know how to make an appearance, don’t they?

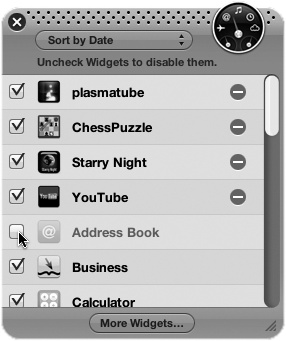

To hide one of Apple’s widgets, or to delete one you’ve installed yourself, use the Widget widget described in Figure 4-20.

To rearrange your widgets as they appear in the Widget bar, open your hard drive→Library→Widgets folder. Here you’ll find the icons for the standard Apple Dashboard widgets. To rearrange them, you have to rename them; they appear on the Widget bar in alphabetical order. (You can also remove a widget for good by deleting it from this folder, if you must.)

Tip

The Dashboard icon also appears in your Dock, just in case you forget the F4 keystroke. On the other hand, if you prefer the keystroke, you can remove the icon from your Dock to make room for more important stuff. Control-click (or right-click) the icon and, from the shortcut menu, choose Remove from Dock.

Figure 4-19. You’ll probably have to scroll the Widget bar to see all the widgets, by clicking the arrows at either end. When you’re finished opening new widgets, close the Widget bar by clicking its ![]() button at the left side of your screen.

button at the left side of your screen.

Figure 4-20. The Widget widget (whose icon appears at lower left in Figure 4-19) opens up this list of widgets. Turn off a checkmark to hide a widget, or click – to completely uninstall any widget you installed yourself. The ones whose boxes aren’t checked are the ones that no longer appear on the Widget bar.

Dashboard is crawling with cool tips and tricks. Here are a few of the biggies:

If you just click an icon on the Widget bar, the widget appears right in the middle of your screen. But if you drag the widget’s icon off the bar, you can deposit it anywhere you like.

There’s a great keystroke that opens and closes the Widget bar: ⌘-= (equals sign). (This keystroke may be different on non-U.S. keyboard layouts.)

To refresh a certain widget—for example, to update its information from the Internet—click it and press ⌘-R. The widget instantly twist-scrambles itself into a sort of ice-cream swirl (you’ve got to see it to believe it) and then untwists to reveal the new data.

You can open more than one copy of the same widget. Just click its icon more than once in the Widget bar. You wind up with multiple copies of it on your screen: three World Clocks, two Stock Trackers, or whatever. That’s a useful trick when, for example, you want to track the time or weather in more than one city, or when you maintain two different stock portfolios.

If you keep the Shift key pressed when you summon Dashboard, the widgets fly onto the screen in gorgeous, translucent, 3-D slow motion. Aren’t you just glad to be alive?

To change the Dashboard keystroke to something other than F4 or F12, choose ![]() →System Preferences, and then click Keyboard→Keyboard Shortcuts.

→System Preferences, and then click Keyboard→Keyboard Shortcuts.

Tip

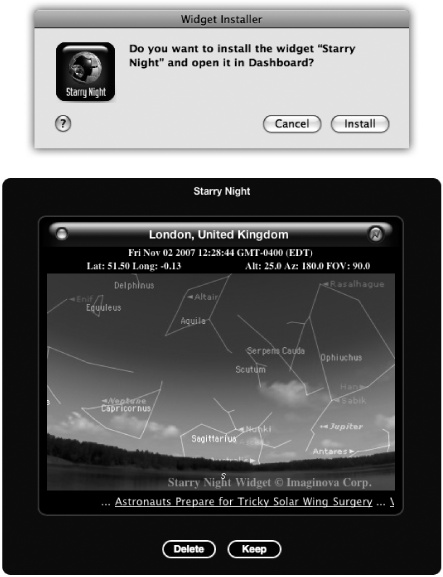

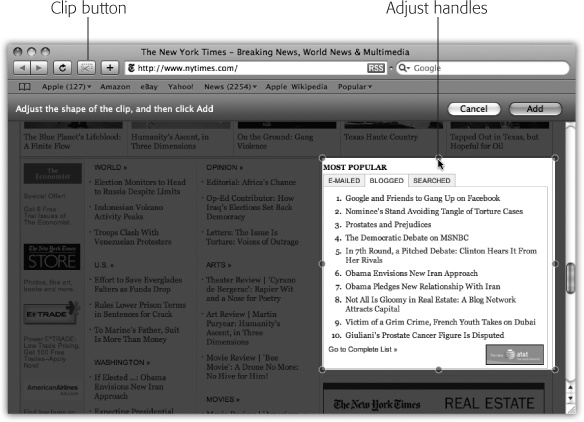

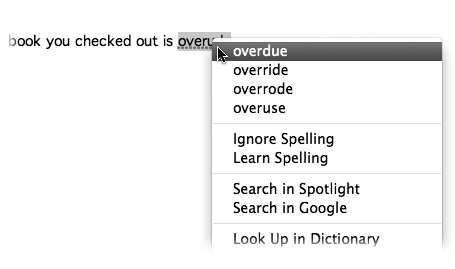

For faster service, Control-click (right-click) the Dashboard icon on the Dock. Choose Dashboard Preferences from the shortcut menu.