If you’re new to the Nikon D90, then you’re probably much more interested in doing some shooting than in reading a book. So, in this chapter I’m going to quickly get you up to speed on the camera’s automatic features so that you can get out the door right away and start using the camera. One of the great features of the D90’s design is that you can use it just like a point-and-shoot camera and then activate more sophisticated controls as you need them. This first chapter explains the fundamental concepts of camera and photographic technique that I’ll build on through the rest of the book.

If you’ve shot only with a point-and-shoot camera, then you’ll find much to like about working with a single-lens reflex (SLR). The bright, clear viewfinder, the ability to change lenses, and the advanced manual controls will give you far more creative power than you probably had on your point-and-shoot camera. If you’re an old-school SLR film shooter, then the switch to digital will bring you huge improvements in workflow, image editing, and overall image quality.

Obviously, with all the power packed into a camera like the D90, you have a lot to learn. However, since the camera also has advanced auto functions, you can get started shooting with it right away and, to a degree, use it just like you used your point-and-shoot.

The best way to learn your camera is to use it, so before I cover the specific parts and components of your D90, you should do a little snapshot shooting just to get your hands on the camera and get a feel for the general control layout.

If you’ve already been playing with your D90, you might have changed some of the internal settings. To ensure that your camera behaves the way that I’ll describe in this book, you should reset to the camera’s defaults.

To reset the D90 to its default settings, follow these steps:

The LCD screen on the top of the camera will go blank for a moment, and when it comes back up, the camera’s essential settings will be reset to their factory defaults. (In Custom Settings of the D90 manual, you’ll find a complete list of the settings that are affected by this operation.)

The D90 has full autofocus and autoexposure features that can make all of the photographic decisions that you need to make in most situations. When in Auto, all you have to do is frame the shot and press the shutter button, and the camera will automatically figure out just about every other relevant setting. However, you still need to know a few things to get the most out of Auto mode.

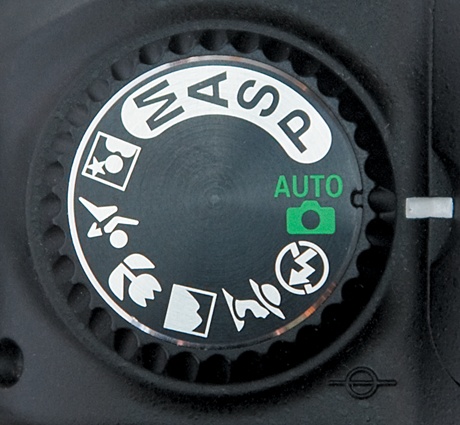

On the top of the D90, on the left side of the camera, is a Mode dial. The mode that you choose with this dial determines which functions the camera will perform automatically and which will be left up to you. So if you want more creative control, then you’ll want to select a mode that offers less automation and leaves more power in your hands.

For snapshot shooting, Auto mode will be your best bet and will make your D90 function much like a simple point-and-shoot camera—but one that delivers the superior image quality of an SLR.

If you haven’t done so already, take the lens cap off the camera. You don’t have to worry about accidentally shooting with it on, because if the lens cap is on, you won’t see anything in the viewfinder. Make sure the switch on the lens is set to autofocus, not manual.

Figure 1-4. The 18–55mm lens kit includes an autofocus switch, and most other lenses will have a similar switch. Make certain it’s set to A.

This next part you probably already know: Look through the viewfinder, and frame your shot. If you have a zoom lens attached to your camera, you can zoom to frame tighter or wider. For now, you don’t have to worry about composition, because I’ll be discussing that in detail later.

With your shot framed, you’re ready to shoot. However, although pressing the shutter button may seem a simple thing, there are some important things to understand about it, because it’s your key to the camera’s autofocus feature.

Once you’ve framed the shot, press the shutter button halfway. When you do this, the camera will analyze your scene and try to determine what the subject is.

There are eleven focus points that the camera can analyze. The D90 will light up all of the focus points that are sitting on what it has determined to be the subject. The lens will focus on that subject.

Figure 1-5. When you half-press the shutter button to autofocus, the D90 will light up the focus spots that it thinks are correct for your subject.

Note that the camera may light up more than one focus point. Often, several potential subjects sit on the same plane (that is, they’re all the same distance from the camera). The D90 will show you all of the focus points that it considers in focus. As long as one of them is on your subject, then it has focused correctly.

When the D90 has achieved focus, it will beep and show a green circle on the left side of the viewfinder status display. (You can see this in the previous figure.)

This half-press of the shutter is a crucial step when using the D90 (or any other autofocus camera). If you wait until the moment you want to take the shot and then press the shutter button all the way down, you’ll miss the shot, because the camera will have to focus, meter, and calculate white balance before it can fire, and these things take time.

Once the camera has told you that it’s focused and ready to shoot, gently squeeze the shutter button. If you jab at the button, you might jar the camera, resulting in a potential loss of sharpness in your image.

REMINDER: “My flash popped up!”

In Auto mode, the D90 will decide whether it needs to use the flash. If it decides that it needs it, the flash will automatically pop up and will be fired when you take the shot.

After you shoot, the camera will display the image for two seconds, giving you a moment to review. When you’re ready to shoot again, follow the same procedure. It’s very important to remember to do a half-press of the shutter to give the camera time to autofocus.

Those are the basics of shooting. Compose your shot, press the shutter button halfway to focus, and then squeeze the shutter button. This is the process that you’ll use no matter what mode you’re shooting in.

Flash Shooting

In a low-light situation, you may see some strange flashes coming from the flash when you press the shutter halfway. These flashes serve to help the camera’s autofocus mechanism “see” when the light is low. Once focus is locked, the camera will beep, indicating that you can press the button the rest of the way, whenever you’re ready, to take your shot.

Spend some time shooting in Auto mode to get a feel for the shutter and basic camera controls.

When you press the shutter button halfway down, several things happen inside the D90’s viewfinder. As I already mentioned, the camera shows you which focus points it has selected for autofocus. It also uses the readout at the bottom of the viewfinder to tell you about its exposure choices and to give you some additional status information.

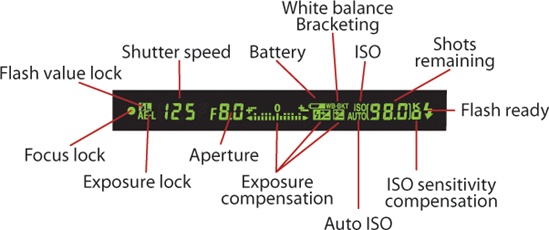

From left to right, the readout works as follows:

When the camera locks focus after you half-press the shutter, then the focus lock circle will appear. If you are using either the flash value lock or autoexposure lock feature, then the appropriate indicator will highlight.

Next, the camera displays its chosen shutter speed and aperture. You’ll learn more about these in Chapter 5.

If you are using exposure compensation features, the appropriate indicators will light. Several other indicators reveal ISO settings, white balance settings, and battery life. For now, all you need to know about these is that the higher the ISO number is, the grainier your images will be.

Next comes the shots remaining indicator. When the shutter button is not pressed, this indicator shows how many shots will fit in the remaining space on your card. When you half-press the shutter, the indicator changes to a lowercase r and shows the number of shots that you can shoot before you will have to wait for the camera’s buffer to empty. The camera has enough onboard RAM to shoot approximately 21 images when in Auto mode.

However, as soon as you shoot, the camera immediately starts writing its buffer out to the storage card. So, if you’re not shooting too fast, you’ll never come close to overrunning the buffer. If you’re shooting bursts of images—at a sporting event, say—then there’s a chance that you’ll fill up the buffer and have to wait a moment before you can shoot again.

You don’t have to wait until all 21 images are available again. As long as the number reads at least 1, you can still shoot.

If the number of remaining images is greater than 1,000, then the camera will switch to an abbreviated view. For example, if your card has room for 1,159 images, the remaining images display will read “1.1 K.”

The S in the upper-right corner indicates that the camera is set to shoot a single image when you press the shutter button down, rather than continuing to shoot for as long as you keep the shutter pressed.

Finally, if the camera has chosen to use the flash, then it will display the

icon. Note that the

icon. Note that the  icon will not appear until the flash is charged and ready to go. How quickly the flash will charge depends on several factors, including the strength of your battery.

icon will not appear until the flash is charged and ready to go. How quickly the flash will charge depends on several factors, including the strength of your battery.

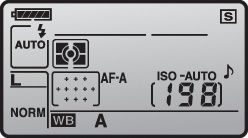

In addition to the in-viewfinder status display, the D90 also shows a lot of status information on the LCD control panel located on the top of the camera. What’s displayed on the screen varies depending on what mode you’re in simply because in some modes you don’t have as much manual control and so don’t need as much status feedback. In Auto mode, your screen should look something like this:

Figure 1-8. In Auto mode, the LCD control panel on the top of the D90 should look something like this.

As you can see, you can easily tell how many shots are remaining, how charged the battery is, and the image format that you’re shooting in. The camera also shows what light metering mode you’re using, which, to be honest, is kind of strange, because you can’t actually change this when shooting in Auto.

Other readouts show which focus point has been selected, your current white balance mode, and whether the camera is set to beep.

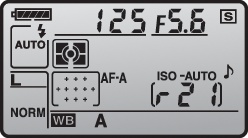

When you half-press the shutter button to tell the camera to focus and meter, it displays its chosen shutter speed and aperture at the top of the status display, as well as the number of shots remaining in the buffer. In later chapters, I’ll explore what these exposure settings mean. (As you’ve already seen, this same data is also shown in the viewfinder status display.)

Figure 1-9. After you half-press the shutter button, the status screen will show the shutter speed and aperture that the camera’s meter selected.

If you don’t do anything else with the camera, the shutter speed, aperture, and remaining buffer displays will go blank after about six seconds to save battery power. Pressing the shutter button halfway again will re-meter and reactivate the display.

Note that even when the camera is turned off, the number of remaining images is still displayed on the control panel. This makes it easy to determine whether the camera’s card has enough space for your intended shoot. If it doesn’t, then you’ll want to change cards or clean off the card that’s in the camera. You’ll learn how to do all of these things later in this book.

If you rotate the power switch to the right, past the On position, a light will illuminate the control panel. For working in low-light conditions, this feature can be essential for reading the control panel.

Shoot some more in Auto mode, and get comfortable with the camera’s controls. Although the camera has a lot of other buttons and dials, you don’t really need to worry about them right now.

If the Viewfinder Is Not Sharp

If you wear glasses and like to remove them when shooting, you can use the diopter control, the small knob next to the viewfinder, to compensate for some near- or farsightedness. Turn the knob until the nine autofocus boxes inside the viewfinder are sharp. Note that the diopter may not be able to completely compensate for extremely bad vision. Also, you’ll have to change it back if you put your glasses back on. If the viewfinder ever inexplicably goes out of focus, it might just be that you bumped the diopter knob. Turn it until focus is restored.

As you’ve seen, the D90 displays your image for a brief time after you shoot. Later, you’ll learn how you can change this time by altering a menu setting. When it comes time to review more than the most recent image, you’ll want to use the camera’s playback mode.

To review your images, press the Playback button ![]() on the back of the camera (obviously, the camera needs to be powered on for this to work).

on the back of the camera (obviously, the camera needs to be powered on for this to work).

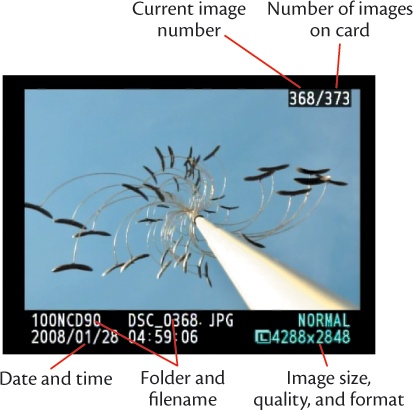

The camera displays the last image that you shot, along with some status information.

Figure 1-10. When you play back an image on the D90, the camera displays some important status information along with your image.

On the back of the camera is a four-way control pad, with a big OK button in the middle. The left and right buttons on this control pad let you navigate forward and backward through your images. Playback mode has a number of other features that you’ll learn about in Chapter 3.

At any time, you can press the Playback button again or give a half-press to the shutter button to return to shooting mode. Note that the D90 can change between shooting and playback modes very quickly, much faster than most point-and-shoot cameras, meaning you don’t have to worry about missing a shot because the camera is locked up in playback mode.

You should now be fairly comfortable with how the D90’s Auto mode works. Since Auto mode takes care of all of the critical decisions regarding camera settings, it’s an ideal mode for snapshot shooting and for getting used to the camera. Before you go off for more shooting, though, let’s take a quick look at some other auto features that you might find useful while getting started.

On the Mode dial, you’ll see a bunch of little icons underneath the Auto setting. These are the D90’s scene modes.

Figure 1-11. These options on the Mode dial are scene modes, which bias the camera’s decisions under specific conditions so that it calculates more appropriate exposures.

Scene modes are also fully automatic, but each one biases some of the camera’s decisions in a certain way so that the camera makes decisions that are more appropriate to particular types of shooting.

Normally, when shooting in Auto mode, the camera will pop up the flash any time it thinks it’s necessary to get a good exposure. If you’re shooting in an environment where you know you don’t want flash—say, a museum or auditorium where flash is not allowed—then you’ll want to choose the Auto (Flash Off) mode, which works just like Auto mode but never uses the flash.

When shooting without the flash, you may find that when you meter, the camera displays “Lo” where it would normally show the shutter speed. When this happens, you’ll also see the exposure compensation display flash. This is the camera’s way of telling you that light is low, so you need to be extra careful to hold the camera steady. Also, be aware that when these indicators are going, there’s a good chance that your resulting image will be too dark.

Portrait mode is ideal for shooting—you guessed it!—portraits. What makes a portrait different from any other type of shot? Typically, in a portrait you want the background blurred out, to bring more attention to your subject. Ideally you also want softer skin tones. Portrait mode biases its exposure decisions to attempt to blur the background.

Figure 1-12. In the upper image, I shot with a deeper depth of field to reveal details in the background. In the lower image, I shot with a shallow depth of field to blur the background out and bring more focus to the subject.

If you want a really soft background, try to position your subject away from the background as much as possible.

Landscape mode can help your landscape shots because it will choose settings that attempt to maximize the amount of your scene that will be in focus. It’s basically the opposite of Portrait mode. Landscape mode also cancels the flash.

Close-up shots of flowers or small objects (what is traditionally referred to as macro photography) are made easier with Close-up mode. In this mode, the camera automatically focus on the subject under the center focus point.

When shooting fast-moving subject matter such as moving wildlife or a sporting event, opt for Sports mode. Sports mode biases the camera’s exposure so that fast-moving objects will be sharp and clear.

When using Sports mode, make sure that the center focus point is on your subject when you press the shutter button halfway down. Unlike other modes, you won’t hear a beep when the camera has locked focus. Instead, the camera will begin beeping continuously to indicate that it is now tracking your subject! Yes, Sports mode uses the D90’s Continuous-servo focus feature to track a moving object and keep it in focus. Sports mode also deactivates the camera’s flash.

Press the shutter to take a shot. If you keep the shutter button held down, the camera will continue to shoot.

One of the biggest mistakes people make when shooting with flash is that they assume that a flash can light up an entire scene, just as if it were daylight. But the flash on any camera has a limited range. It’s usually enough to light up your subject but not your background, leaving you with a subject that appears to be standing in the middle of a dark limbo.

REMINDER: Night Portraits Require Still Subjects

When shooting with Night Portrait mode, the flash will fire, but the camera’s shutter will stay open for a bit. So, it’s important to tell your subject not to move until after you say so.

While the rest of this book is going to cover just about every aspect of shooting in great detail—from holding the camera to processing images—you can do a lot with the Auto capability that you’ve already learned about. Since the camera is taking care of most of the technical issues for you, it’s a good time to practice handling the camera and composing shots. I’m going to talk about composition in great detail in Chapter 8. For now, consider the following tips when shooting snapshots.

When shooting a portrait or candid snapshot of someone, you usually do not need a lot of headroom, unless you want to show something about the environment they’re in.

For example, in this image, the extra headroom doesn’t add anything to the picture. In fact, it’s kind of distracting and takes up space that could be used to show a larger image of the person. In the next image, I fill the frame with more of the person. You can see a better view of them, but you still get enough background detail to get an idea of the environment they’re in.

Figure 1-16. In this image I’ve filled the entire frame, which results in a larger view of the subject.

“Fill the frame” is one of the most important compositional rules you can learn, no matter what type of image you’re shooting. Don’t waste space in the frame. Empty space in your image is space that could be used to provide a larger, better view of your subject.

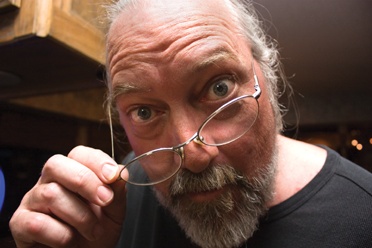

Another portrait tip: You don’t have to show a person’s entire face or head. Don’t be afraid to crop them and get in close for a very personal shot.

Figure 1-17. When shooting portraits, don’t be afraid to get in close. You don’t have to show a person’s whole head. It’s fine to crop.

You can get close either by standing physically close to the person or by standing farther away and zooming in. However, as you’ll see in Chapter 6, these two options produce very different images, so you’ll want to think about which approach is right for your subject.

When shooting a portrait of someone who’s looking off-frame, consider leading the subject. When someone is looking out of the frame, we’re more interested in the space that’s in front of them than the space that’s behind them. Even if we can’t see what it is they’re looking at, we still want to feel extra space that sits in the direction they’re looking.

It’s easy to forget about that third dimension that you can move in and shoot all of your shots while standing up. Don’t forget that you can bend your knees (or even lie on the ground) to get a different angle. Getting down low is especially important when shooting children and animals, since it puts you at a more personal, eye-to-eye relationship with them.

Don’t pay attention just to your subject; remember that they’re also standing in front of something. Make sure there’s nothing “sticking out” of their head or juxtaposed in a distracting way.

This is loosely related to the previous tip. Be careful about shooting your subject in front of a brightly lit background, such as a window, or shooting into the sun. Although sometimes you can use such an approach to great effect, for simple snapshots you’ll get better results keeping a close eye on the backlight in your shots.

If you find yourself shooting someone in front of a window or bright light, try to move them or yourself so that the light is not directly behind them.

Figure 1-21. The window is throwing off the camera’s meter. Shooting with flash helps illuminate the foreground and evens out the exposure.

The problem with bright lights in the background of a shot is that they confuse the camera’s light meter. When a bright light appears in the background, the camera meters to properly expose that bright light. This usually means the foreground is left underexposed and appears too dark.

In Auto mode, the D90 should recognize such a situation and automatically pop up the flash. The flash will serve to light up the foreground, creating a more even exposure with the background.

You’ll learn more about metering, as well as other strategies for handling backlighting, in Chapter 7. For now, even if you aren’t sure exactly how to handle such a situation, at least start learning to recognize when you’re shooting in this type of difficult lighting condition.

Although the flash on the D90 can do a good job of illuminating a subject, you have to remember that it has a limited range. Anything beyond about 13 feet from the camera will fall out of the flash’s range and not be illuminated at all. So if you’re standing at night across the street from a person or building and you shoot a picture with the flash popped up, you’ll probably get a shot that’s completely black.

For this situation, flash is not the answer. Instead, you’ll need to employ some low-light shooting strategies, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 7.

Use Night Portrait Mode

As you saw earlier, flash range can also impact the background of your scene. If your subject is in range of the flash but your background isn’t, you can end up with people standing in totally black, limbo environments. See Night Portrait Mode earlier in this chapter.

There’s one mistake that all beginning photographers make: They think an expert photographer sees a scene or subject, determines how to best frame and expose it, and then takes a picture of it. If you describe this process to an “expert” or “professional” photographer, they’ll most likely laugh.

The fact is, even the most accomplished photographer rarely gets it right the first time and so rarely shoots only one exposure of a subject. Instead, they work their subject—something we’ll be talking about a lot through the rest of this book.

Very often, the only way to find the best composition or angle on a shot is to move around. Get closer and farther, stand on your tiptoes, squat down low, circle the object—and look through the viewfinder the whole time, and shoot the whole time.

If you like, review your shots and try again. Often, photography is like sculpture. You can’t see the finished shot right away. Instead, you have to “sculpt” the scene, trying different vantage points until you find the angle that makes for the most interesting composition and play of light, shadow, and color.

Remember: When a subject catches your eye, the chances that you happen to be standing in the very best spot in the world and that you happen to be the perfect height to photograph it are pretty slim. So, go out now and practice shooting broad coverage of some scenes. Stay moving, play with distance and angle, and notice the difference in what you see in the viewfinder, what you recognize while you’re shooting, and what the final results look like on the camera’s screen.

You may be surprised to find that the final images you like best are the ones that are very different from what you originally envisioned.

Get The Nikon D90 Companion now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.