How Git Thinks About Merges

At first, Gitâs automatic merging support seems nothing short of magical, especially compared to the more complicated and error-prone merging steps needed in other version control systems.

Letâs take a look at whatâs going on behind the scenes to make it all possible.

Merges and Gitâs Object Model

In most version control systems, each commit has only

one parent. On such a system, when you merge

some_branch into my_branch, you

create a new commit on my_branch with the changes

from some_branch. Conversely, if you merge

my_branch into some_branch, this

creates a new commit on some_branch containing the

changes from my_branch. Merging branch A into

branch B and merging branch B into branch A are two different

operations.

However, Git designers noticed that each of these two operations

results in the same set of files when youâre done. The natural way to

express either operation is simply to say âMerge all the changes

from some_branch and

another_branch into a single branch.â

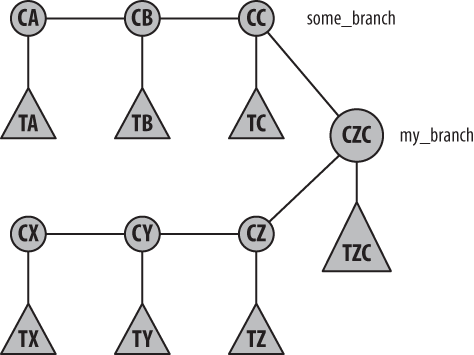

In Git, the merge yields in a new tree object with the merged files, but it also introduces a new commit object on only the target branch. After these commands:

$git checkout my_branch$git merge some_branch

the object model looks like Figure 9-10.

Figure 9-10. Object model after a merge

In Figure 9-10, each

C is a commit object

and each xT represents the corresponding tree ...x

Get Version Control with Git now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.