Chapter 1. What Is a Game?

GAMES AND PLAY ARE NOT THE SAME THING.

Imagine a boy playing with a ball. He kicks the ball against a wall, and the ball bounces back to him. He stops the ball with his foot and kicks it again. By engaging in this kind of play, the boy learns to associate certain movements of his body with the movements of the ball in space. We could call this associative play.

Now imagine that the boy is waiting for a friend. The friend appears, and the two boys begin to walk down a sidewalk together, kicking the ball back and forth as they go. Now the play has gained a social dimension; one boy’s actions suggest a response, and vice versa. You could think of this form of play as a kind of improvised conversation, where the two boys engage each other using the ball as a medium. This kind of play has no clear beginning or end; rather, it flows seamlessly from one state into another. We could call this streaming play.

Now imagine that the boys come to a small park, and that they become bored simply kicking the ball back and forth. One boy says to the other, “Let’s take turns trying to hit that tree. You have to kick the ball from behind this line.” The boy draws a line by dragging his heel through the dirt. “We’ll take turns kicking the ball. Each time you hit the tree you get a point. First one to five wins.” The other boy agrees and they begin to play. Now the play has become a game; a fundamentally different kind of play.

What makes a game different? We can break down this very simple game into some basic components that separate it from other kinds of play.

- Game space:

To enter into a game is to enter another kind of space where the rules of ordinary life are temporarily suspended and replaced with the rules of the game. In effect, a game creates an alternative world, a model world. To enter a game space, the players must agree to abide by the rules of that space, and they must enter willingly. It’s not a game if people are forced to play. This agreement among the players to temporarily suspend reality creates a safe place where the players can engage in behavior that might be risky, uncomfortable, or even rude in their normal lives. By agreeing to a set of rules (stay behind the line, take turns kicking the ball, etc.), the two boys enter a shared world. Without that agreement, the game would not be possible.

- Boundaries:

A game has boundaries in time and space. There is a time when a game begins—when the players enter the game space—and a time when they leave the game space, ending the game. The game space can be paused or activated by agreement of the players. We can imagine that the players agree to pause the game for lunch, or so that one of them can go to the bathroom. The game will usually have a spatial boundary, outside of which the rules do not apply. Imagine, for example, that spectators gather to observe the kicking contest. It’s easy to see that they could not insert themselves between a player and the tree, or distract the players, without spoiling or at least changing the game.

- Rules for interaction:

Within the game space, players agree to abide by rules that define the way the game world operates. The game rules define the constraints of the game space, just as physical laws, like gravity, constrain the real world. According to the rules of the game world, a boy could no more kick the ball from the wrong side of the line than he could make a ball fall up. Of course, he could do this, but not without violating the game space—something we call cheating.

- Artifacts:

Most games employ physical artifacts; objects that hold information about the game, either intrinsically or by virtue of their position. The ball and the tree in our game are such objects. When the ball hits the tree a point is scored. That’s information. Artifacts can be used to track progress and to maintain a picture of the game’s current state. We can easily imagine, for example, that as each point is scored, the boys place a stone on the ground or make hash marks in the dirt to help them keep track of the score—another kind of information artifact. The players are also artifacts in the sense that their position can hold information about the state of a game. Compare the position of players on a sports field to the pieces on a chessboard.

- Goal:

Players must have a way to know when the game is over; an end state that they are all striving to attain, that is understood and agreed to by all players. Sometimes a game can be timed, as in many sports, such as football. In our case, a goal is met every time a player hits the tree with the ball, and the game ends when the first player reaches five points.

We can find these familiar elements in any game, whether it is chess, tennis, poker, ring-around-the-rosie, or the games you will find in this book.

The Evolution of the Game World

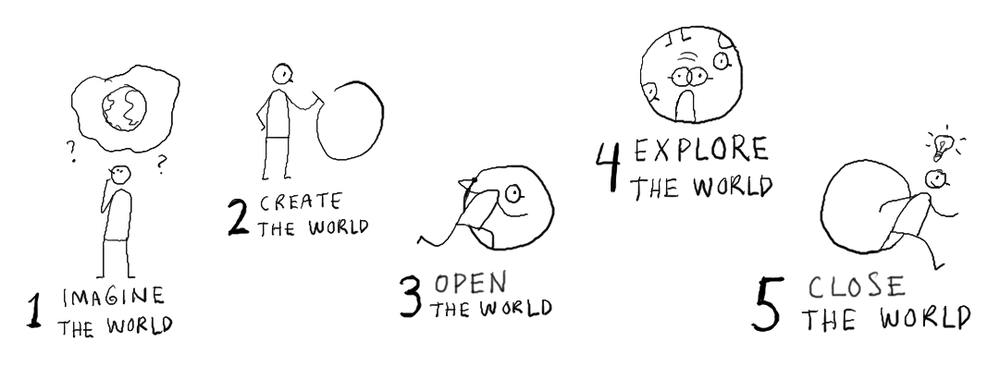

Every game is a world which evolves in stages, as follows: imagine the world, create the world, open the world, explore the world, and close the world. Here’s how it works:

- Imagine the world.

Before the game can begin you must imagine a possible world; a temporary space, within which players can explore any set of ideas or possibilities.

- Create the world.

A game world is formed by giving it boundaries, rules, and artifacts. Boundaries are the spatial and temporal boundaries of the world; its beginning and end, and its edges. Rules are the laws that govern the world; artifacts are the things that populate the world.

- Open the world.

A game world can only be entered by agreement among the players. To agree, they must understand the game’s boundaries, rules, artifacts; what they represent, how they operate, and so on.

- Explore the world.

Goals are the animating force that drives exploration; they provide a necessary tension between the initial condition of the world and some desired state. Goals can be defined in advance or by the players within the context of the game. Once players have entered the world they try to realize their goals within the constraints of the game world’s system. They interact with artifacts, test ideas, try out various strategies, and adapt to changing conditions as the game progresses, in their drive to achieve their goals.

- Close the world.

A game is finished when the game’s goals have been met. Although achieving a goal gives the players a sense of gratification and accomplishment, the goal is not really the point of the game so much as a kind of marker to ceremonially close the game space. The point of the game is the play itself, the exploration of an imaginary space that happens during the play, and the insights that come from that exploration.

Imagine the world, create the world, open the world, explore the world, and close the world. The first two stages are the game design, and the remaining three stages are the play.

You can see that a game, once designed, can be played an infinite number of times. So, if you’re playing a predesigned game there will be only three stages: open the world, explore the world, and close the world.

Gamestorming is about creating game worlds specifically to explore and examine business challenges, to improve collaboration, and to generate novel insights about the way the world works and what kinds of possibilities we might find there. Game worlds are alternative realities—parallel universes that we can create and explore, limited only by our imagination. A game can be carefully designed in advance or put together in an instant, with found materials. A game can take 15 minutes or several days to complete. The number of possible games, like the number of possible worlds, is infinite. By imagining, creating, and exploring possible worlds, you will open the door to breakthrough thinking and real innovation.

The Game of Business

Let’s begin by boiling the “game of business” down to its most basic components.

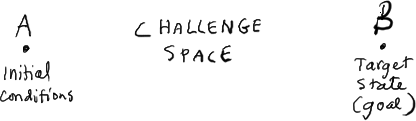

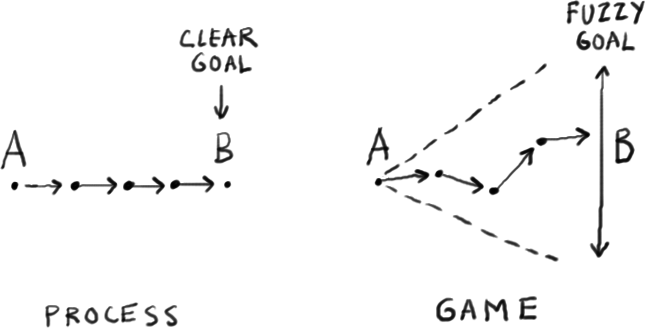

Business, like many other human activities, is built around goals. Goals are a way we move from A to B; from where we are to where we want to be. A goal sets up a tension between a current state A—an initial condition—and a targeted future state B—the goal. In between A and B is something we can call the challenge space; the ground we need to cover in order to get there.

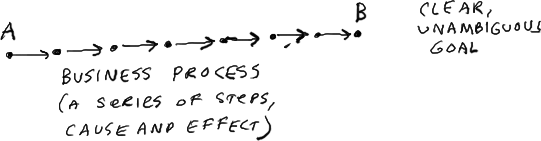

In industrial work, we want to manage work for consistent, repeatable, predictable results. Industrial goals are best when they are specific and quantifiable. In such cases, we want to ensure that our goals are as clear and unambiguous as possible. The more specific and measurable the goal is, the better. When we have a clear, precise industrial goal, the best way to address the challenge space is with a business process—a series of steps that, if followed precisely, will create a chain of cause and effect that will lead consistently to the same result.

But in knowledge work we need to manage for creativity—in effect, we don’t want predictability so much as breakthrough ideas, which are inherently unpredictable. In any creative endeavor, the goal is not to incrementally improve on the past but to generate something new.

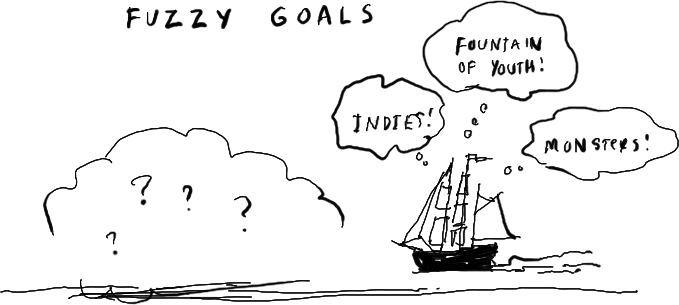

New, by definition, means “not seen before.” So, if a team wants to truly create, there is simply no way to precisely define the goal in advance, because there are too many unknowns. Embarking on this kind of project is akin to a voyage of discovery: like Columbus, you may begin your journey by searching for a route to India, but you might find something like America; completely different, but perhaps more valuable.

Fuzzy Goals

Like Columbus, in order to move toward an uncertain future, you need to set a course. But how do you set a course when the destination is unknown? This is where it becomes necessary to imagine a world; a future world that is different from our own. Somehow we need to imagine a world that we can’t really fully conceive yet—a world that we can see only dimly, as if through a fog.

In knowledge work we need our goals to be fuzzy.

Gamestorming is an alternative to the traditional business process. In gamestorming, goals are not precise, and so the way we approach the challenge space cannot be designed in advance, nor can it be fully predicted.

While a business process creates a solid, secure chain of cause and effect, gamestorming creates something different: not a chain, but a framework for exploration, experimentation, and trial and error. The path to the goal is not clear, and the goal may in fact change.

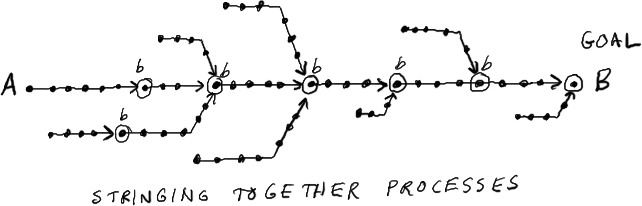

This is true at both a micro scale and a macro scale. To create a complex industrial product requires the close integration of many processes. When you string a bunch of processes together you will see a branching structure with many dependencies. As long as every step is followed precisely and nothing changes along the way, you will achieve your goal reliably and predictably every time. The management challenge is one of precision, accuracy, and consistency.

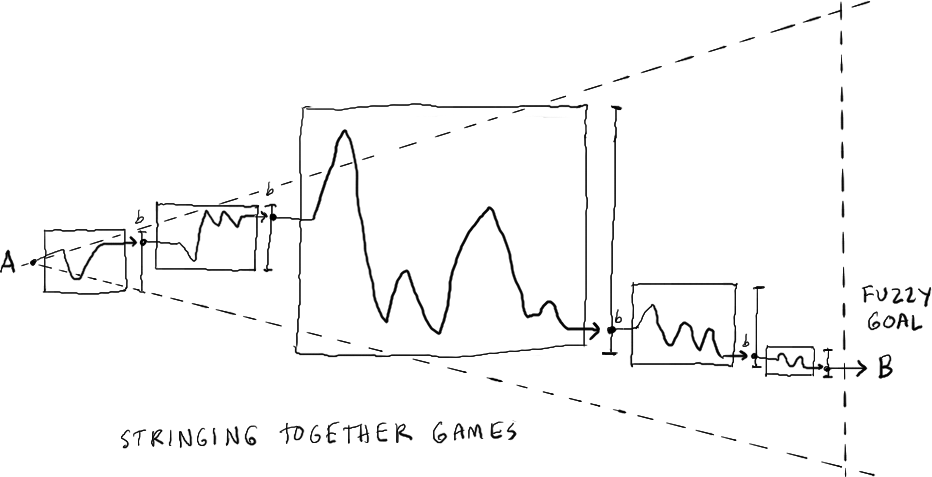

Managing creative work requires a different approach. Because the goal cannot be determined precisely in advance, a project must proceed based on intuition, hypotheses, and guesses. This kind of approach is very familiar in the world of the military, where ambiguous, uncertain, volatile environments are the norm.

We all know that the military uses games and simulations as a way to practice for war. But they also use something called a concept of operations, or CONOPS, to (1) create an overall picture of the system and the goals that they want to achieve, and (2) communicate that picture to the people who will work together to reach those goals. A concept of operations is a way to say, “Given what we know today, here is how we think this system works, and here is how we plan to approach it.”

A concept of operations is a way to imagine a world.

This may seem like a big challenge, but think about our two boys playing ball: the world we create does not necessarily need to be complicated to be interesting and to help us move forward. Imagining a world can be as simple or as complex as you want to make it, depending on your goal, your situation, and the time you have available.

Unlike a large and complex process, which must be planned in advance, a concept of operations is under constant revision and adjustment based on what you learn as you go. So, yes, you need to have a goal, but since you really know very little about the challenge space, it’s very likely that your goal will change as you try out ideas and learn more about what works and what doesn’t.

In gamestorming, games are not links in a chain, so much as battles in a campaign.

In a paper titled “Radical innovation: crossing boundaries with interdisciplinary teams,” Cambridge researcher Alan Blackwell and colleagues identified fuzzy goals (they called it a pole-star vision) as an essential element of successful innovation. A fuzzy goal is one that “motivates the general direction of the work, without blinding the team to opportunities along the journey.” One leader described his approach as “sideways management.” Important factors identified by the Cambridge research team include the balance between focus and serendipity, and coordinating team goals and the goals of individual collaborators.

Fuzzy goals straddle the space between two contradictory criteria. At one end of the spectrum is the clear, specific, quantifiable goal, such as 1,000 units or $1,000. At the other end is the goal that is so vague as to be, in practice, impossible to achieve; for example, peace on Earth or a theory of everything. While these kinds of goals may be noble, and even theoretically achievable, they lack sufficient definition to focus the creative activity. Fuzzy goals must give a team a sense of direction and purpose while leaving team members free to follow their intuition.

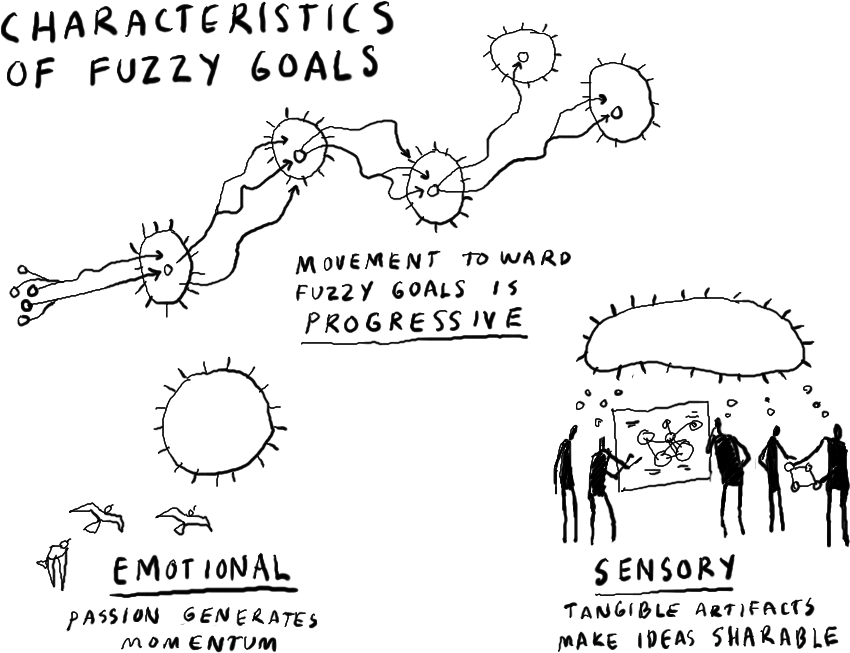

What is the optimal level of fuzziness? To define a fuzzy goal you need a certain amount of ESP: fuzzy goals are Emotional, Sensory, and Progressive.

- Emotional:

Fuzzy goals must be aligned with people’s passion and energy for the project. It’s this passion and energy that gives creative projects their momentum; therefore, fuzzy goals must have a compelling emotional component.

- Sensory:

The more tangible you can make a goal, the easier it is to share it with others. Sketches and crude physical models help to bring form to ideas that might otherwise be too vague to grasp. You may be able to visualize the goal itself, or you may be able to visualize an effect of the goal, such as a customer experience. Either way, before a goal can be shared it needs to be made explicit in some way.

- Progressive:

Fuzzy goals are not static; they change over time. This is because, when you begin to move toward a fuzzy goal, you don’t know what you don’t know. The process of moving toward the goal is also a learning process, sometimes called successive approximation. As the team learns, the goals may change, so it’s important to stop every once in awhile and look around. Fuzzy goals must be adjusted (and sometimes, completely changed) based on what you learn as you go.

Innovative teams need to navigate ambiguous, uncertain, and often complex information spaces. What is unknown usually far outweighs what is known. In many ways it’s a journey in the fog, where the case studies haven’t been written yet, and there are no examples of where it’s been done successfully before. Voyages of discovery involve greater risks and more failures along the way than other endeavors. But the rewards are worth it.

Game Design

If you want to get started with gamestorming right away, you can flip to the collection of games that begins with Chapter 5 and start making things happen in your workplace. But if you want to really master gamestorming, you’ll need to learn how to design your own games, based on your goals and more specific to what you want to accomplish.

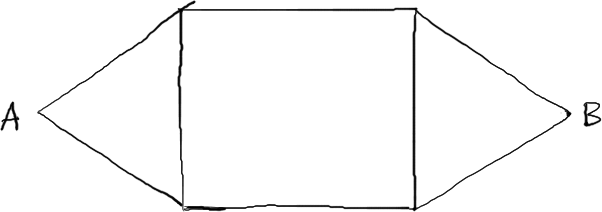

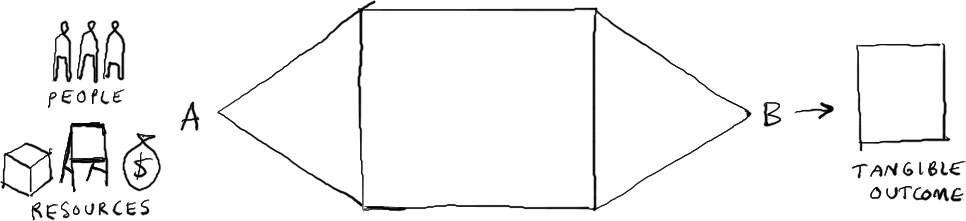

Let’s start with this idea. A game has a shape. It looks something like a stubby pencil sharpened at both ends. The goal of the game is to get from A, the initial state, to B, the target state, or goal of the game. In between A and B you have the stubby pencil—that’s the shape you need to fill in with your game design.

- Target State:

To design a game you begin with the end in mind: you need to know the goal of the game. What do you want to have accomplished by the end of the game? What does victory look like? What’s the takeaway? That’s the outcome of the game, the target state. I like to think of the target state in terms of some tangible thing, which can be anything from a prototype to a project plan or a list of ideas for further exploration. Remember, it helps if a goal is tangible; it gives people something meaningful to shoot for and gives them a sense of accomplishment when they have finished. And when they are done, they’ll be able to look at something they created together.

- Initial State:

We also need to know what the initial state looks like. What do we know now? What don’t we know? Who is on the team? What resources do we have available?

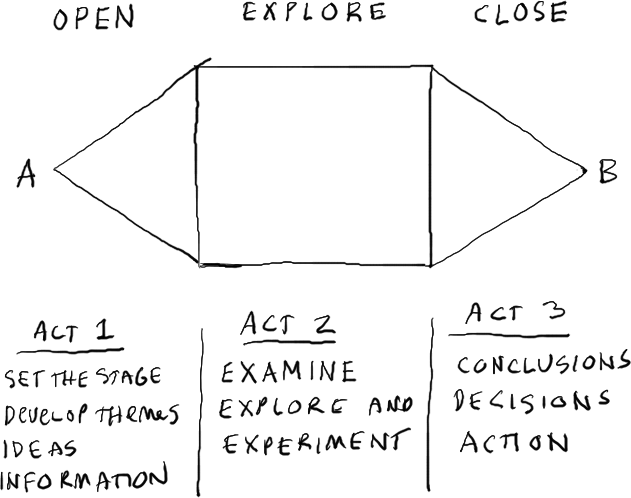

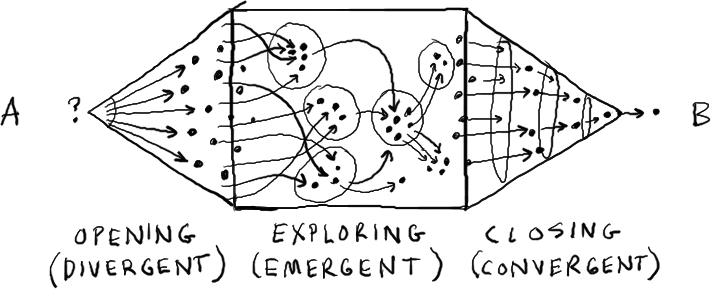

Once we understand the initial and target states as best we can (remember that many goals are fuzzy!), it’s time to fill in the shape of the game. A game, like a good movie, unfolds in three acts.

The first act opens the world by setting the stage, introducing the players, and developing the themes, ideas, and information that will populate your world. In the second act, you will explore and experiment with the themes you develop in act one. In the third act, you will come to conclusions, make decisions, and plan for the actions that will serve as the inputs for the next thing that happens, whether it’s another game or something else.

Each of the three stages of the game has a different purpose.

- Opening:

The first act is the opening act, and it’s all about opening—opening people’s minds, opening up possibilities. The opening act is about getting the people in the room, the cards on the table, the information and ideas flowing. You can think of the opening as a big bang, an explosion of ideas and opportunities.

The more ideas you can get out in the open, the more you will have to work with in the next stage. The opening is not the time for critical thinking or skepticism; it’s the time for blue-sky thinking, brainstorming, energy, and optimism. The keyword for opening is “divergent”: you want the widest possible spread of perspectives; you want to populate your world with as many and as diverse a set of ideas as you can.

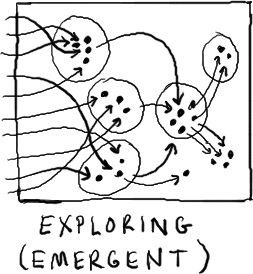

- Exploring:

Once you have the energy and the ideas flowing into the room, you need to do some exploration and experimentation. This is where the rubber hits the road, where you look for patterns and analogies, try to see old things in new ways, sift and sort through ideas, build and test things, and so on. The keyword for the exploring stage is “emergent”: you want to create the conditions that will allow unexpected, surprising, and delightful things to emerge.

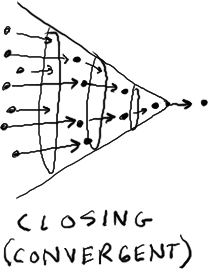

- Closing:

In the final act you want to move toward conclusions—toward decisions, actions, and next steps. This is the time to assess ideas, to look at them with a critical or realistic eye. You can’t do everything or pursue every opportunity. Which of them are the most promising? Where do you want to invest your time and energy? The keyword for the closing act is “convergent”: you want to narrow the field in order to select the most promising things for whatever comes next.

When you are designing an exercise or workshop, you want to think like a composer, orchestrating the activities to achieve the right harmony between creativity, reflection, thinking, energy, and decision making. There is no single right way to design a game. Every company, and every country, has its own unique culture, and every group has its own dynamic. Some need to move faster than others, and some need more time for reflection.

For example, in Finland, long silences where people consider and reflect on a question before answering are not uncommon. This can feel very uncomfortable if you’re not accustomed to that culture. You’ll need to do your homework and compose a flow that’s right for the group you are working with, and the situation you are working on.

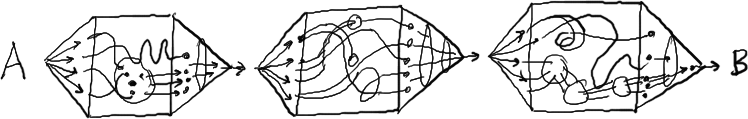

Opening, exploring, and closing are the core principles that will help you orchestrate the flow and get the best possible outcomes from any group. A typical daylong workshop may be filled with many games that can be linked to each other in an infinite variety of ways. Games can be played in series, where the outcomes of one game create the initial conditions for the next.

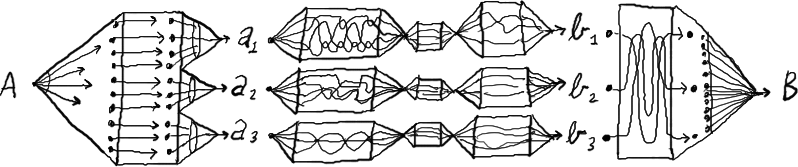

Here’s a series where three games are played in a row. Each game has a clear opening, exploration, and closing. The outcome of each game serves as the input for the next. This kind of design is very simple, clear, and easy for everyone in the group to understand.

In the next series, three longer, more intensive games are interspersed with two shorter games. The shorter games might give the groups a chance to loosen up a bit between more intensive activities.

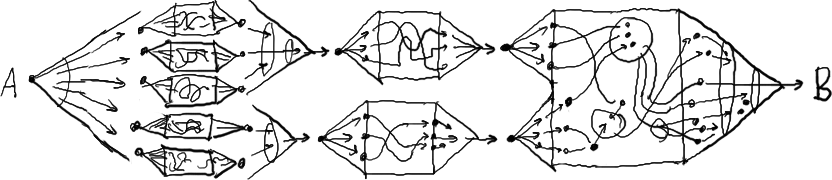

Sometimes, especially with a larger group, it makes sense to pursue multiple goals. A key concept in game design is a variation on opening and closing called break out/report back, where a larger group diverges by breaking out into smaller subgroups, plays a game or two, and converges by reporting back the outcome of their efforts to the larger group. This is a way to keep groups small and dynamic, and also increase the variety of ideas, by playing multiple games in parallel.

People also need time to reflect on ideas. Breakouts (or breaks) can be a good time for this. Break out/report back is a way to balance sharing and reflection and to create quiet time. For example, you can ask people in a group to spend time working on an individual exercise which they can then share with the group.

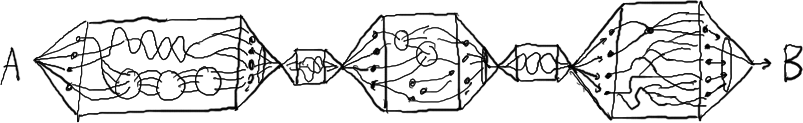

Here’s a series where an initial, opening session reveals three different goals that can be pursued in parallel breakout groups. At the end of the series the three groups’ outcomes are shared in a report-back session with the larger group.

Here’s a series where the outcomes of the first game generate inputs for five games, which generate inputs for two games, which generate the input for a single, longer game. This kind of string might indicate a workshop including multiple ideas and agendas that need to be worked on in parallel.

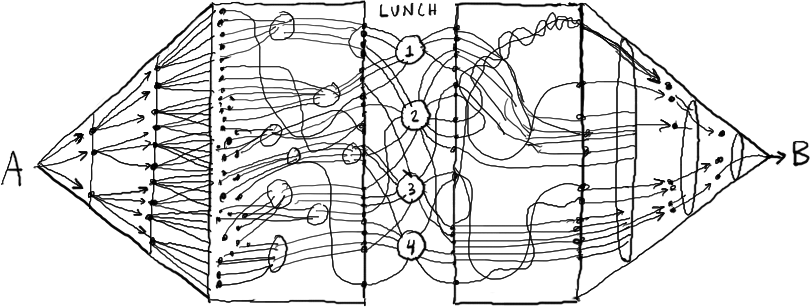

Here’s a daylong game where a big chunk of the morning is spent on divergent activities, generating a lot of ideas and information, and the exploration phase is split into two parts, with a break for lunch, followed by an afternoon of convergent activities that flow into a single outcome. The group will lunch together at four tables for informal conversation and reflection on the morning’s activities before going into the afternoon session. This kind of design might be appropriate for a group where everyone had some level of interest in every component of the day, and nobody wanted to be left out of any part of the game.

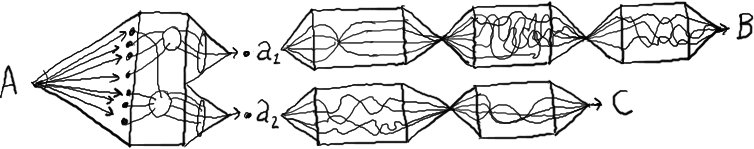

Sometimes you make discoveries while a game is underway that require a change in direction. In the following series, the initial opening and exploration revealed a new goal that the team had not anticipated. The group agreed to break into two subgroups; one group pursued the original goal and the second worked on the new goal.

OK, so it’s time to compose a game, or maybe a series of games. Where do you begin? What do you compose with? Remember that gamestorming is a way to approach work when you want unpredictable, surprising, or breakthrough results—a method for exploration and discovery.

Think about the people who explored the natural world for a moment: people like Columbus, Lewis and Clark, Ernest Shackleton, and Admiral Byrd. Imagine what it must have felt like to be one of these explorers. You are searching for something that you may not find. You will almost certainly find things you don’t expect. You have only a vague idea of what you will encounter along the way, and yet, like a turtle, you must carry everything you need on your back.

Get Gamestorming now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.