Chapter 1. Our Emotional Relationship with Technology

TAKE A MOMENT TO imagine what your home will look like in 10 years. Maybe you imagine living in that house. You know the one. It’s a pristine space—all curved lines and smooth, white surfaces. Objects are minimally designed with intelligence embedded deep within, or maybe with a projected layer of augmented reality. You might imagine wandering from one behaviorally and emotionally optimized choice to the next, occasionally enlisting the help of a chatbot here or a robot companion there. Or maybe you don’t have to imagine.

In 2015, Target launched Open House in San Francisco. Part retail space and part lab, the project uses interactive storytelling as a way to help people picture the smart home of the future. Open House, designed by Local Projects, is arranged like a 3,500-square-foot home that just happens to be filled with internet-connected everything. The products are present day, from a kitchen with smart coffee pots to a bedroom with a Withings smart baby monitor to a living room outfitted with Sonos speakers and a Nest thermostat. With transparent walls lit by Philips Hue lighting and sensors that detect your presence, the house pops up conversation bubbles above each product.

Figure 1-1. Clearly, the quintessential home of the future (source: Target)

Beyond crafting a tangible future for purchase, Open House reveals a vision of ease and convenience, running on an invisible layer of technology. On the surface, Target is promoting what technology of the near future can do. Look a little closer and you can sense something else. This future is about how we feel.

More and more, we assume that the good life runs on technology. As designers, developers, and makers, we take care in crafting experiences that make life easier. Yet, we don’t devote as much attention to how technology runs much deeper. In this chapter, we begin by looking at the ways technology is inextricably intertwined with our inner lives and what it means for design.

Inventing Our Best Lives

Depending on how you look, you can glimpse two futures for our lives with technology. Put on your rose-colored virtual-reality headset, and you’ll see the promise of unparalleled ease. Scroll, bleary-eyed, through your social media feed and it’s a cacophony of voices foretelling the collapse of the world as we know it. What can these future visions tell us about our emotional relationship with technology?

FRICTION-FREE TECH UTOPIAS

Tech utopias are few and far between in science fiction. Star Trek or The Jetsons and a handful of novels are all we have to bring us from the brink of despair. A positive future world of technology has, however, been vividly imagined for consumers.

Target’s Open House is just one version of the home of the future in a long line of future home fantasies. From the 1933 Homes of Tomorrow exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair, to Disney’s Home of the Future of the 1950s, to the contemporary Google House of Dubai, future homes invariably feature smart ovens, robot butlers, and beds that make themselves. Food is prepared at the push of a button. Clothes clean themselves. Life is leisurely.

The office of the future has the same glossy vibe. At the office, a central physical space with meditation pods coexists peacefully with flickering screens projecting dashboards on a conveniently placed wall here and there. Remote work, situated in the high-tech home of the future, transports us via hologram.

Visions of smart cities are sprinkled with pixel stardust, too. From moving sidewalks to hoverboards, from flying cars to autonomous vehicles, fantasies of future cities place ease at a premium. We see this future vision spread from city to city—Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs creating a high-tech future city on the Toronto waterfront, and the German town of Duisburg partnering with Huawei to infuse daily living with technology. Outside the city, a dusting of Elon Musk’s solar-tiled rooftops might be visible to the trained eye.

At home or at work, utopians’ futures look remarkably similar—clean and minimal, the soft whir of subtle technology. And our smart world seems to hum along on universally agreed-upon values of ease to fuel productivity at work and leisure at home. Emotionally speaking, you might say it’s serene. But it’s difficult to tell; emotions are muffled.

Maybe that’s because people only rarely inhabit this future. Homes, workplaces, even whole cities are mostly empty. Colorful lights bounce off slick surfaces, while the robots roll quietly through deserted hallways. A world that’s been so carefully calibrated for comfort doesn’t engage our participation, making it difficult to imagine the kind of life we might make there.

Or maybe we imagine ourselves in front of that smart mirror (Figure 1-2) that seems ubiquitous—to tech insiders, at least. I like to think of it as the Lacanian mirror phase of technology. We begin to recognize ourselves in the future, but it’s a challenge. This future lacks the human touch.

Figure 1-2. The smart mirror doesn’t make it easier to picture ourselves in the future (source: MirroCool)

DYSTOPIAN FUTURES

Contrast the sparse future of tech utopias with the chaotic clamor of dystopia. Swipe through the news any given day, and you’ll hear predictions of smart robots taking our jobs, autonomous cars taking out innocent pedestrians, and mass virtual-reality escapism. Or you might read perilous projections of a near future in which technology harvests all your data, reducing your life’s purpose to a few salient data points that are superimposed over security-camera captures. You end the day, staying up later than you intended, to watch just one more episode of Black Mirror or Westworld.

You can find a dystopian future almost anywhere you click. The relentless repetition of negative headlines comes at the pace of innovation. The vast worlds of compelling sci-fi dystopias are populated with carefully crafted details that fuel our dismal dreams. From time to time, we can spot these fictional futures come true. From TASERs to animojis (Figure 1-3), gadgets created to support a fictional dystopia become a cliché embedded in our all-too-real present day. Falling into dystopian rumination about the coming end times turns out to be effortless, especially when it’s been so fully realized.

Figure 1-3. When sci-fi futures surface in the present, should we call them self-unfulfilling prophecies? (source: @blackmirror)

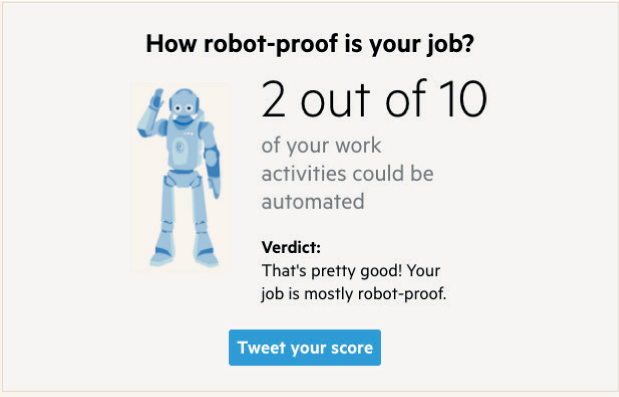

Dystopias don’t just limit our imagination, they might already be having a real effect in our everyday lives. According to the World Health Organization, more than 300 million people of all ages suffer from depression.1 Although there are a range of factors that lead to depression, data from the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index tells us that unemployed adults are about twice as likely to be depressed as people employed full-time.2 Anxiety about looming job losses might already be contributing to a mental health crisis. Imagine hearing that your job is easily automated, and that you need to reskill with money you probably don’t have. For those who have jobs that seem safer from automation, there’s a sense of relief tinged with guilt followed by apprehension. It’s only a matter of time, after all (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. No reason to be smug; automation will come for you, too (source: McKinsey Global Institute)

So, here we are, trapped between a placid future of convenience and a post-apocalyptic hellscape where anxiety-plagued humans have designed their own obsolescence. To complicate things just a bit more, these binary futures play out in our present-day triumphs and trials with technology.

The Present: It’s Complicated

Most of us struggle a bit with being human in the digital age. We sleep poorly. Our necks are sore from bending over our phones. Social media quietly chips away at our self-worth while heightening our sense of collective anxiety. We feel isolated despite being more connected than ever. Study after study tells us that heavy use of technology is making us depressed.

Yet, we can catch a little glimpse of our best selves in each innovation. From fitness bands to smart speakers, from travel tools to productivity apps, technology promises, and often delivers, confidence. Social media often cultivates compassionate action. Skype calls with far-flung friends can be joyful.

Just as our futures are alternately calm and crazed, our present is a whipsaw of wonder and worry. Even so, the triumphs and tribulations of our personal experience with technology aren’t typically framed in emotional terms.

STREAMLINING THE WORLD, STREAMLINING US

One way that technology strives to create calm or contentment is by streamlining our lives, especially those aspects that seem mundane. Convenience has emerged as a value, even a way of life. With a promise of effortless efficiency, technology frees us up to pursue what we really want to do, even if we aren’t always sure what that is.

Some of us do benefit from home automation and work productivity tools. Amazon’s Echo orders our groceries when we don’t have time to pop by the store, and Nest turns down thermostats while we’re away. Google Docs and to-do apps help us stay organized and get work done faster.

Sometimes, though, the streamlining doesn’t quite work as intended. Productivity apps don’t make us more productive but give us another app to manage. Work communication tools, from email to Slack, create yet another channel to actively monitor. GPS will give us the fastest route, but it might just end up taking us out of the way. We’ll never know, of course, because we forgot how to read maps. Apple Watch promises that we can “do more in an instant.” Or is it “fill up every instant with more to do”?

As technology has crept into our personal lives, smart seems a little dull. Google Photos categorizes and organizes our lives by theme. As much as Pinterest might feed our artistic impulses, it does so in a standardized way. Fitness trackers tell us precisely how many steps we’ve taken but reveal nothing about the journey itself.

Our days can seem like a sequence of answers to questions we outgrew in grade school: What do you like? Will you share it? Do you love it? Likewise, it can trivialize what should be important. When a friend posts of a pet’s passing, it’s a little too easy to click the sad face rather than to send a note. Thanks to predictive text, emojis, and automated rejoinders, we readily dismiss uncomfortable moments rather than doing the hard work of maintaining relationships.

This quiet efficiency has another unhappy side effect—it streamlines us. In a given hour, you might have an argument with your spouse, feel elated at a small victory at work, experience deep gratification at a note from a colleague, look wistfully at a picture of the beach from last summer, feel excited to set up plans with a friend at a restaurant in the evening. Our technology doesn’t acknowledge all that.

Instead, it tends to interpret who we are to fit neatly into predetermined, ad-friendly categories. “Married, currently interacting with two other people; at work with IP address x in location y; likes beaches; favors restaurants near work; booked a hotel last July for four days; one female tagged in photo; face matches user.” As much as details keep flowing in, technology somehow misses the mark. These data-verified assumptions prompt offers and suggestions and impersonal personalizations that threaten to reduce us to a shadow of ourselves.

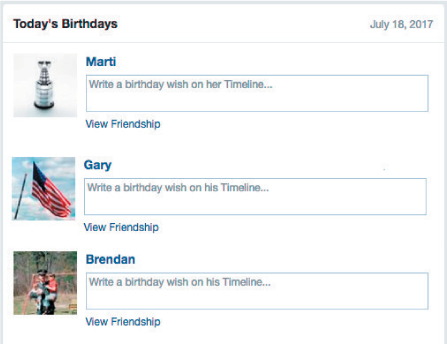

Even though some of us may be smugly sipping Soylent, reveling in the efficiency of scientifically engineered nutrition and unmatched ease of preparation, more of us will tire of it. We’ll miss the texture, the flavor, the effort, and all the interesting mistakes we make preparing our meals. It might feel great to not miss a friend’s happy birthday, but does it feel great to have “happy birthdays” stack up like tidy bricks on our walls, only to prompt another round of obligatory liking and thanking? (See Figure 1-5.)

Figure 1-5. Making quick work of happy birthdays, oh snap

The cult of convenience fails to acknowledge that difficulty is core to human experience. The joy of a slow journey, the satisfaction that comes from challenges, the confidence that comes from learning through trial and error trump convenience. All our focus on fewer steps hasn’t resulted in human flourishing. Perhaps it has even made us more conscious of time.

SAVING TIME, WASTING TIME

When the promise of technology is framed around ease and efficiency, we consider its breakdown in increments of time. Time is the unspoken, but deeply embedded, value. It’s so pervasive that we might not even notice it anymore.

One way we frame our bad feelings about technology is as a distraction. This isn’t new. Aldous Huxley in Brave New World Revisited (Harper & Row, 1958) wrote with dismay about our “infinite appetite for distraction” in the form of news. Years later, Neil Postman attributed our hunger for distraction to television (Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business [Methuen, 1985]). In The Shallows (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), Nicholas Carr writes, “The net is designed to be an interruption system, a machine geared to dividing attention” (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010).

Now, distraction centers on the gravitational pull we feel to our phones. When we are idle, we check our phones. When we are bored, we check our phones. When we can’t fall asleep, we check our phones. Distraction takes us away from all of the fulfilling things we should be doing. Hint: those things we should be doing probably don’t involve endlessly scrolling social media feeds (Figure 1-6).

Figure 1-6. A block of Japanese text and a bunny never fail to spark joy (source: @carrot666)

But, then, what does count? When I read news, am I wasting time because I should be working instead? Is it time misspent if I watch cat videos, but not if I watch a TED talk? Does browsing reviews on Goodreads count? What if I don’t intend to read the book? It’s difficult to say. Time online is often viewed as a monolith. Even if we admit that all of our time online might not be wasted, we still try to minimize it. Time “offline” is considered intrinsically better.

Distraction is more than a minor irritant, to be sure. What you focus on minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day begins to add up. When our attention is diverted or we simply have too much drawing our attention, we have a hard time focusing on what’s important. All these distractions could theoretically ensure that you forget to lead the life you want to lead.

And it’s more than distraction. When we feel out of control, it veers into addiction. Internet addiction is a real condition, matter of debate, and widely accepted universal state of mind. Study after study finds a strong positive correlation between heavy smartphone use and anxiety, depression, and other symptoms of mental illness. We can quibble over the details, but the toll it takes is real.

But what are we addicted to, anyway? Is it the phone itself? Some studies make the case. We get pangs of anxiety when separated from our phones. Other studies suggest that we are less focused when our smartphone is nearby. Our brains flood with oxytocin when we hear our phones — we might literally love our iPhones. Even the sound triggers love and loss. The object, security.

Social media, in particular, has been declared addictive in studies and by experts. A friend likes your photo, another friend comments on your post, and we get a kind of rush and then a letdown. Maybe we are addicted to the approval we get?

Or are we addicted to the content, interactions, the stuff of the app? It’s difficult to untangle the device from the app from the content. Entrepreneurs study addictive behavior, after all, to help create it. Product teams work hard to engage us, hijacking our time.

Perhaps we are simply addicted to distraction itself. Like gamblers who get in a “machine zone,” we are caught up in the rhythm of repetition. An alternate reality flow state drives us toward interactions that are only occasionally satisfying. I wonder if the real fear is that our addiction to machines make us more machine-like.

EMOTIONAL UPS AND DOWNS

When the ideal technology frees up our time, it makes sense to frame the downsides in terms of attention. Tech insiders and the general public have become attuned to the unreasonable demands technology can make on our time. The demands on our emotions, however, are the current that runs beneath.

Our emotional life online can be uplifting—affirmations from friends, genuine offers of help, convivial communities. Once in a while, there’s that great feeling of the immensity and connectedness of humanity. Or just the pure joy of being back in someone’s life again.

Online, people feel free to explore new identities. The online disinhibition effect, first noted by psychologist John Suler (Psychology of the Digital Age: When Humans Become Electric [Cambridge University Press, 2016]), means that people don’t behave as they would face-to-face. Sometimes this disinhibition can be positive. It can let people feel that they can truly be themselves. But it can also be negative. Bullying and trolling might be attributed, in part, to a false sense of anonymity.

Almost since social media came to be, it’s been studied for negative emotional impact. From social comparison to fear of missing out to bullying or worse, social media seems to amplify the worst in us. With all the perfect vacations and beautiful babies and romantic gestures, social comparison has become a daily routine rather than an occasional meditation. Is everyone faking it? Maybe. But then we begin to worry that we’re the imposters with everyone else being so consistently brilliant. When we aren’t comparing, we feel that pang of missing out on the good life that everyone seems to be enjoying without us.

Empathy online, when we do stumble on it, can be genuine. It feels good to tap a sad reaction or share a cheery gif. It feels like lending support or showing you care. And it does, a little. But we worry that we will begin to prefer diminished substitutes. After all, it’s easier to leave a message than actually talk on the phone. It’s easier to email rather than call. It’s easier to click a heart rather than leave a comment. We worry that we will become streamlined to convey information rather than connect with grace.

Life online, for some of us, requires what I’ll call continuous partial empathy. Whether it’s dealing with harassment on Twitter or offering support on Facebook or shouldering care on GoFundMe, many of us spend our time supporting friends, family, and a wide range of people we might not know very well at all. At scale, it can take a toll on emotional well-being, leaving us drained or stressed.

Many experiences, as currently designed, thrive on extreme emotions. Jonah Berger, in Contagious: Why Things Catch On (Simon & Schuster, 2013), found that anger spreads fastest on social network. Negative emotions like outrage and fear activate. Although positive emotions are less viral, pronounced emotions like awe, amazement, and surprise drive engagement, too. This explains why our life with technology can feel like an emotional rollercoaster.

More and more, technology is designed to fuel a cycle of emotions. Whether it’s “solving” a low-key negative emotion like boredom with a curiosity-induced headline or conjuring high-intensity outrage for clicks, the behavioral approach to design kills the pain temporarily. And then, if it’s successful, repeatedly.

Glance at a notification on your phone, or pull to refresh your email, or endlessly scroll Facebook or Twitter, and you might or might not find what you are seeking. When you do, you get a little burst of dopamine and you feel good. The good feeling doesn’t last for long and the false sense of urgency creates a new source of stress. When you don’t find it you just keep going anyway. Is the answer opting out?

DETOX, RETOX

Just as our futures are sketched in binary opposition, so it seems our present-day experience of technology ping-pongs between highs and lows. Our approach to this conundrum is predictably binary, too. Experts encourage us to “detox,” to take some time offline. Whether it’s a no-smartphone family dinner, a weekend off maybe at a Restival, or a vacation without WiFi at Camp Grounded, taking a break restores balance. A detox feels virtuous at first, but somehow ends back where we started: reaching for the phone 200 times or more a day.

Even though it’s certainly not a bad idea to put down your device, it’s not a successful strategy for balance in the long term. It doesn’t create long-lasting change. The Light Phone (Figure 1-7), a minimalist phone with limited features, was funded at light speed on Kickstarter at the same time Nokia 3310 relaunched its iconic “dumb phone.” Apps like Flippd and Moment encourage a technology time-out. Google launched, to much acclaim, tools to help us track our time online and occasionally take a breather.

Figure 1-7. Minimalist devices still require a “real” companion phone (source: Light Phone)

As much as it might help us become aware of our destructive habits, this will produce new anxieties, too. Dread will likely mount as we warily watch our online intensity indicator move from green to red. The count of hours online will no doubt end in unhealthy social comparison. Nudges to go offline will be met with annoyance.

Design that gives us a breather from a downward spiral into the sixth level of notification hell is a noble effort, but it doesn’t get us closer to a sustainable relationship with technology either. Reminding people of their time spent online is more abdication than answer. Detox design ignores the bigger picture—technology silently scripts our conversations and behaviors, and even our thoughts and feelings.

Design Designs Us

Internet critics tell us that our brains are being rewired. Well, of course. Wouldn’t it be strange if we were still expected to think, feel, and behave the same way, despite all this new technology?

Even a simple walk through the woods is haunted by the world in our pockets. We might frame our walk with TripAdvisor reviews. We are conscious of notifications accumulating as we walk along. In turn, each step tempts us to check on our health app. The lovely scene demands to be shared via Instagram. There might be some Pokémons to collect just beyond that tree (Figure 1-8). Even if we’ve left our phone behind, we can’t experience that walk without technology. In other words, our existential concerns are underscored by lolcats.

Figure 1-8. Pokémon GO frames the modern condition (source: Niantic)

Technology doesn’t just frame how we perceive the world, it alters our behaviors. Nest prompts us to rewire our homes to control our comfort. Lyft lets us stay a little longer at that party. Echo encourages us to change the kind of detergent we buy so that we can order it through Amazon. Snapchat scripts our conversations. Facebook shifts how we tackle community problems.

Technology reframes our relationships. It might prompt us to see others too often in terms of endorsements or obligations: posts to like, comments to make, people to follow define relationships in a tightly circumscribed way. But it shapes our relationships in the so-called real world, too. Facebook underpins my own small community, which means we can band together in a power outage or pass on a pair of ice skates with ease.

Technology is tied with our identity. We’ve become shape shifters, moving between roles we perform for the world and for ourselves. Whether a keynote speaker on Twitter, doting parent on Facebook, or angry anonymous commenter on the New York Times website, we try on different roles.

Technology shapes our emotions in ways we are only beginning to understand, too. It creates new emotions, like “three-dot anxiety” as we wait for a text; vemödalen, the frustration of photographing something amazing when thousands of identical photos already exist; or FOMO, the fear of missing out. Then there’s that feeling when tech creates emotions that we haven’t yet named. As the connective tissue of our modern lives, inside and out, our relationship with technology is emotional.

Why Emotionally Intelligent Design?

Technology has expanded to fill every open space in our lives. And it occupies new spaces that we didn’t even realize were there. Yet, we still seem reluctant to acknowledge the emotional layer of our experience. At its worst, technology fills us with rage or unease. At its best, we think technology should be calm, or once in a while, deliver a ping of delight. That’s an extremely limited emotional range.

The hyper-connected, autonomous, conversational, increasingly AI-powered devices might be called “smart” on a good day. Sure, they’re code-smart, but they aren’t people-smart. Technology can’t tell whether we feel happy or sad, much less rejected or bored or optimistic or petulant or “hangry.” Technology doesn’t respond any differently to a soothing voice or crazed screaming (not that I would know, of course). Technology doesn’t encourage us to be aware of our own emotions or the emotions of those around us. And that’s a problem.

Designers, developers, information architects, content strategists, and now script writers, AI trainers, and countless others responsible for designing technology have treated emotion more like an achievement to be unlocked. Journeys start low and end high. We trace the happy path between human and machine, apprehensively contemplating the possibility of many more unhappy paths. Just in case, we hide a little surprise here and there, hoping to soothe hurt feelings.

New technology is prodding us toward a reconsideration of emotion. Voice humanizes interactions, so much so that therapy chatbots can really help people work through difficult times and home assistants gamely fill in for children’s playmates. Social robots dance and play music and pull up recipes while we cook dinner. Virtual reality beckons us to reflect deeply on the lives of others, from the plight of refugees to the experience of solitary confinement. Each imperfectly realized, yet undeniably emotional.

THE NEW EMOTIONAL DESIGN

The next wave of tech will venture further into emotional territory. Smart speakers, autonomous vehicles, televisions, connected refrigerators, and mobile phones will soon be able to read emotional cues. Your fridge might work with you on stress eating. Your bathroom mirror might sense that you’re feeling blue and turn on the right mood-enhancing music. Your email software will ask you to reflect before you hit send. The most meaningful technologies are very likely to be the most emotionally intelligent.

Ready or not, those of us working in tech need to not just acknowledge the complexity of emotional experience but find new ways to design for it.

Emotion has already become an organizing principle for design in other contexts. Cities from Bogota, Columbia, to Somerville, Massachusetts, have been using happiness as a method to guide urban planning. Architecture has long considered how the shape of a building can inspire anything from a moment of awe to an emotional climate of civic engagement. Creating convivial warmth in our homes, whether by seeing if objects “spark joy” or create a sense of hygge (the Danish concept of inviting coziness), is a full-blown trend.

What’s key to all these movements is that emotional resonance is not a gift we bestow on the world with design. It’s made by designers and people from all walks of life together. It doesn’t take just one shape, it takes many shapes. It doesn’t take us out of the world, it gives us new ways of being in the world.

Something as complex as emotionally intelligent design can’t be summarized into a quick list of features. We can’t add it as a step in the process: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and—ta dah!—social and emotional well-being. It’s not a set of tips to polish the experience. What you’ll find here is not a hierarchy or a diagram or a handy set of quick-hit methods.

Instead, I’ll propose this: emotional intelligence as a way to change our perspective on design. More than anything, the latest thinking on emotion helps us to see the world in a new way. As we go along in this book, we pause to consider a broad range of research on emotion—from emotional intelligence to happiness to personality models to affective forecasting. And we combine that with movements in the design world, including value-sensitive design and speculative design and our own tradition of emotional design.

Think of each chapter as a way to intentionally tune in to emotion in a new way. At the beginning, or the next beginning (some might call it the end), or somewhere in the middle, these exercises can help build emotionally sustainable relationships with the technology.

Let’s start.

Get Emotionally Intelligent Design now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.