The commands discussed in this section are simple and familiar to most Unix users. For this reason, they’re often overlooked in system administration discussions. However, I believe you’ll find them to be an indispensable part of your repertoire. One other important communications mechanism is electronic mail (see Chapter 9).

A system administrator frequently needs to send a message to a

user’s screen (or window). write is

one way to do so:

$ write

username[tty]where username indicates the user to whom

you wish to send the message. If you want to write to a user who is logged in more than

once, the tty argument may be

used to select the appropriate terminal or window. You can find out

where a user is logged in using the who command.

Once the write

command is executed, communication is established between your

terminal and the user’s terminal: lines that you type on your terminal

will be transmitted to him. End your message with a CTRL-D. Thus, to

send a message to user harvey for which no reply

is needed, execute a command like this:

$write harveyThe file you needed has been restored.Additional lines of message text^D

In some implementations (e.g., AIX, HP-UX and Tru64), write may also be used over a network by

appending a hostname to the username. For example, the command below

initiates a message to user chavez on the host

named hamlet:

$ write chavez@hamletWhen available, the rwho

command may be used to list all users on the local subnet (it requires

a remote who daemon be running on the remote system).

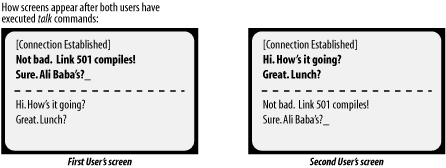

The talk command is a more

sophisticated version of write. It

formats the messages between two users in two separate spaces on the

screen. The recipient is notified that someone is calling her, and she

must issue her own talk command to

begin communication. Figure

1-1 illustrates the use of talk.

Users may disable messages from both write and talk by using the command mesg n (they can include it in their .

login or .

profile initialization file).

Sending messages as the superuser overrides this command. Be aware,

however, that sometimes users have good reasons for turning off

messages.

If you need to send a message to every user on the system, you

can use the wall command. wall stands

for “write all” and allows the administrator to send a message to all

users simultaneously.

To send a message to all users, execute the command:

$wallFollowed by the message you want to send, terminated with CTRL-D on a separate line^D

Unix then displays a phrase like:

Broadcast Message from root on console ...

to every user, followed by the text of your message. Similarly,

the rwall command sends a message

to every user on the local subnet.

Anyone can use this facility; it does not require superuser

status. However, as with write and

talk, only messages from the

superuser override users’ mesg n

commands. A good example of such a message would be to give advance

warning of an imminent but unscheduled system shutdown.

Login time is a good time to communicate certain types of information to users. It’s one of the few times that you can be reasonably sure of having a user’s attention (sending a message to the screen won’t do much good if the user isn’t at the workstation). The file /etc/motd is the system’s message of the day. Whenever anyone logs in, the system displays the contents of this file. You can use it to display system-wide information such as maintenance schedules, news about new software, an announcement about someone’s birthday, or anything else considered important and appropriate on your system. This file should be short enough so that it will fit entirely on a typical screen or window. If it isn’t, users won’t be able to read the entire message as they log in.

On many systems, a user can disable the message of the day by creating a file named . hushlogin in her home directory.

On Solaris, HP-UX, Linux and Tru64 systems, the contents of the file /etc/issue is displayed immediately before the login prompt on unused terminals. You can customize this message by editing this file.

On other systems, login prompts are specified as part of the terminal-related configuration files; these are discussed in Chapter 12.

Get Essential System Administration, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.