Chapter 1. Scaling Hiring: Growing the Team

Great vision without great people is irrelevant.

Jim Collins, Good to Great (HarperBusiness)

Growing a team requires dedicated effort by team leaders to identify, recruit, and hire the best candidates, and probably a lot more effort than you think. You need a well-designed recruiting process that channels this effort to yield the results you want: great hires. This is especially critical in a teamâs early days, since the founders and early employees form the bedrock of what the company hopes to become. Hiring poorly is often worse than not hiring at all.

In this and the next two chapters, we outline a scalable hiring process that can take a team from single digits to hundreds of employees. Weâll explain how to evaluate candidates efficiently and accurately, minimize bias in the recruiting process, and maximize the chance that your new hires will be strong contributors. But first, letâs discuss the principles that form the foundation of any effective recruiting process.

Hiring to Scale

Teams that need to hire are trying to bridge the gap between what they can do today and what they need to do in the future. These could be skill gaps, such as the group of hardware engineers who realize their product needs a major software component. Or they could be capacity gaps, such as when the founding team realizes they are unable to keep up with customer demand for new features and support requests. In either case, what should team leaders do to best fill those gaps and help the team succeed?

Key Principles

Before outlining the full recruiting lifecycle, letâs cover the key principles for hiring.

Hire for talent

It goes without saying that you want to hire the best employees you can. By âbest,â we mean the employees that can contribute the most to team success over the long term. Often, teams focus too much on filling specific short-term skill gaps, or simply getting a âwarm bodyâ on board who can handle the work that isnât currently getting done. Itâs critical to remember that the hires you make at your current stage will set the tone for hires you make in later stages.

Hire for the team

Every team is different, and in larger companies, so is the organization that surrounds them. The best person for your team may be very different than the best person for your friendâs team at a nearby startup. We often hear the advice that you should only hire âAâ players, but we believe that building an âAâ team is more important. A super-talented hire who has very different values can pull a team apart rather than bringing it together. We will share insights on how to identify individuals who can magnify the teamâs strengths, who are genuinely passionate about the product and will reinforce the value of being an open, product-focused organization.

Minimize bias

A biased interview process is a flawed interview process. Besides the inherent unfairness to the individuals involved, bias reduces the chance of finding the best hire for your team by allowing irrelevant factors such as race, gender, or age to influence the hiring decision. This chapter explains why diversity matters when youâre building teams, and what simple changes can be made to reduce the impact of hidden bias in the interview process.

Donât cut corners

A rigorous interview process is analogous to a rigorous code review process. Finding bugs in code review is much less expensive than finding them in production, and similarly, rejecting a candidate that is wrong for your team during the interview process is much less expensive than hiring them and dealing with the resulting problems later. This is sometimes described as âoptimizing for false negatives.â Later in this chapter, we discuss how to do this appropriately, as well as cover when itâs strategically sound to take a risk on a candidate who may not seem like a perfect fit.

Treat candidates with respect

Candidates often talk to friends, family, and colleagues about their interview experience, and may even post summaries on sites like Glassdoor and Quora. Providing a great experience will improve your chances of landing the candidate you want and may encourage others to apply. A bad experience can not only lose you a candidate but might also prevent their entire network from interviewing with you! Your goal should be to have every candidate walk away from the interview wanting to work for your company, whether you decide to make an offer or not.

Know how much risk to take

In times of hyper-growth, you may feel pressure to take risks in order to meet your growth targets. You might take a chance on a borderline candidate or blindly hire a referral because one of your cofounders heard good things about them. But we advise a more cautious path. There are enough distractions in your organization already without the added disruption of having to terminate the new hire that didnât work out. Firings will happen regardless, but they happen even more frequently when you take more risk in the hiring process.

There are certainly arguments for taking more risk and tolerating false positives in order to find a diamond in the rough. As Henry Ward explains in his article, âHow to Hireâ: âDo not be afraid of hiring false positives. Give people chances. Be afraid of missing the 20x employee.â Itâs certainly possible to construct a system in which hiring decisions are made more loosely, relying instead on a more rigorous on-the-job evaluation process that identifies bad hires quickly. But even when you make a quick decision that someone needs to leave, it takes time and energy to manage those people out, and time and energy are especially precious resources during hyper-growth. This is why our default advice is to not take too much risk.

Know when to listen to your gut

Experienced interviewers often develop a strong gut feeling that kicks in 10 or 15 minutes into an interview. Because gut feelings can be a source of bias, they should not replace a thorough hiring decision; instead, they are an indicator that you should dig deeperâinto the candidate, and your own reactions.

Hiring for Diversity

Because bias can affect every stage of the process, each chapter on scaling hiring includes suggestions about how to reduce bias and minimize its impact. But before getting into specifics, letâs first define what is impacted by bias: team diversity. Some characteristics of team diversity are race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, physical ability, and sexual orientation. A more complete list can be found at CodeOfConduct.com. Too often, discussions of diversity narrow in on one or two characteristics rather than taking a broader view.

Beyond the inherent unfairness to those affected, bias reduces the effectiveness of your recruiting efforts by unnecessarily narrowing the field of qualified candidates. From a purely pragmatic view, excluding certain groups only serves to limit the size of an otherwise huge talent pool.

The result is a less diverse team which is likely to perform worse than more diverse teams, particularly in situations that require creativity and innovation. For a more complete discussion of the research, see the McKinsey reports âWhy Diversity Mattersâ and âThe Case for Team Diversity Gets Even Betterâ.

Diverse teams are also more likely to understand the perspectives of their customers. A homogeneous workforce (typically young, white, heterosexual males in the tech industry) might not question product decisions are insensitive or hurtful to their users. There are plenty of examples we can cite, such as Snapchat releasing âanimeâ and âbob marleyâ filters that were immediately condemned as harkening back to the days when white artists performed in âyellowfaceâ or âblackfaceâ makeup.

In general, the problem you face when scaling a startup is that you naturally tend to hire people who are similar to one another from the very start, in part because itâs often the referral networks of the founding team members that lead to early hires. This intimacy quickly becomes a disadvantage. Once you have a homogeneous core team, people with other traits and backgrounds are less likely to join the company. As an example, letâs say you have 50 employees, none of whom have kids. Will someone with three children join that team, especially if there are often meetings at 8:00 p.m., when they need to put their kids to bed? And who wants to be the first woman on a âbroâ team? Unreflective homogeneity can prove daunting and prohibitive to potential new hires, and quite reasonably so.

Form the founding team and choose early hires based on who shares values and ideas with youâpeople who are passionate about the mission of the team. If all these people are white and male, so be it. If they are black and female, so be it. After that, however, diversifying the team must be a high priority. Weâll talk about how to accomplish this goal throughout this chapter.

Also note that creating an inclusive workplace is essential to maintaining team diversity. It doesnât much help to hire a diverse team if you canât retain them. Inclusion is covered in more detail in âBuilding an Inclusive Workplaceâ.

The Hiring Process

With this overview in place, letâs dive into the details of a typical hiring process, describe some warning signs that indicate that the process isnât scaling, and discuss some ideas for how to adjust as you continue to grow.

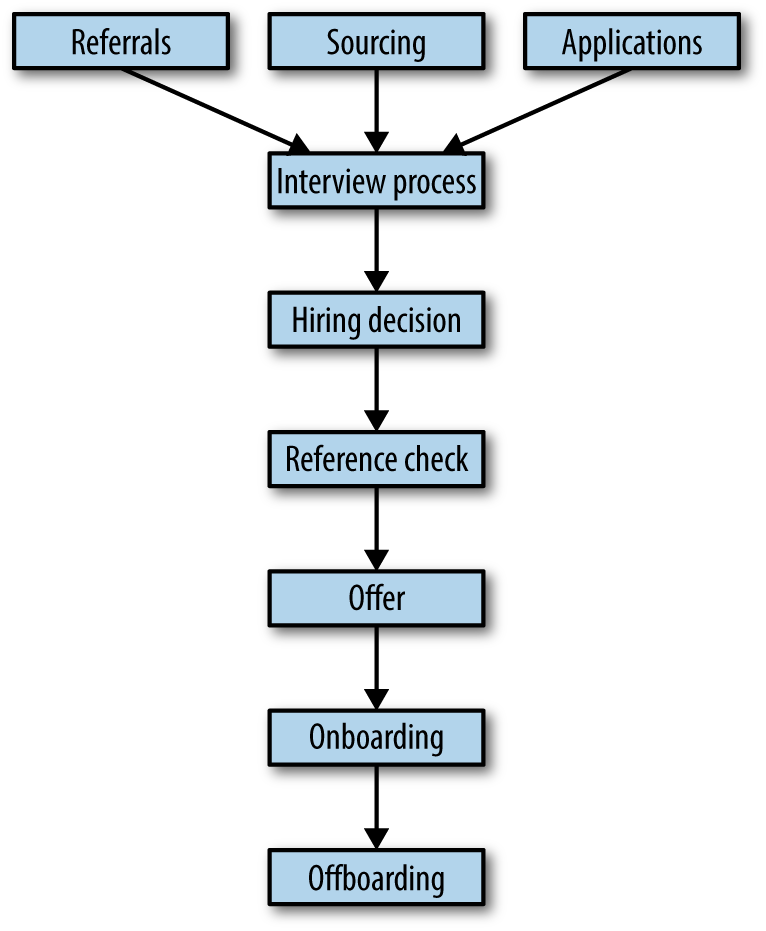

Figure 1-1 illustrates a typical hiring process. Candidates come in from three different sources and go through a set of screens and interviews. Next, a âhireâ or âno-hireâ decision has to be made. If itâs a âhireâ and the candidate accepts, they go through on-boarding before settling into their new role. We also include the off-boarding process because it can help you gain valuable insights into your hiring and organization. This isnât the only way to hire, but the broad strokes shown here are how the majority of tech companies approach hiring.

Figure 1-1. Hiring process illustrated

Finding People

There are three main sources for new candidates: a candidate applies directly, is sourced by a recruiter, or is referred by someone. In Chapter 3 we will discuss another way of getting candidatesâacquiring a company in order to hire some or all of their employees. But in the following sections, weâll examine in detail the three most common ways to find people.

Referrals

Arguably the most effective method for finding new candidates is through referrals. A referral means that current employees (or other friends of the company, such as advisors, investors, and board members) identify potential candidates from their existing networks.1 Ideally, this is someone the referrer has worked with in the past, so the referrer knows the personâs qualifications, talents, and values. Referrals have a lot of advantages over other channels, but also a few caveats you should be mindful of. The advantages include:

- Reduced cost and effort

- Although you may pay a referral bonus, which weâll cover later, you donât have to pay a recruiter to source the candidate. And the process tends to be much faster than when you hire from other sources.2

- Retention

- Referred employees stay longer at the company, and employees who made successful referrals stay longer than employees who didnât.3

- Success rate

- Referred candidates are usually already motivated when entering the hiring process, as they have already spoken with current employees about the company beforehand. They come in much better informed about the company than other candidates, and because of this tend to have compatible values, work quality, work style, and a good fit with the culture. And perhaps most importantly, people tend to refer people they think will do a good job and are thus hired at a higher rate than other sources.4

A high rate of referrals can be a very good indicator of company health. Conversely, a lack of referrals can mean employees are unhappy with their jobs or unsure about the future of the company. Tracking referral data can provide insight into the morale of the team. Watch for trends here!

But there are also disadvantages to relying too much on referrals in the hiring process; essentially, groups tend to become groups because theyâre relatively alike. White males are likely to know other white males. So hiring more diverse team members through referrals alone becomes extremely difficult. Referrals, in other words, can dilute diversity right out of the gate, especially if the founding team itself lacks diversity. Research from Freada Kapor-Klein5 shows that, statistically, if we are white, then 90% of our friends are also white. If we are African American, 85% of our friends are as well.

Be careful to avoid creating subgroups comprising friends who were already friends before they joined. They can end up building their own culture, and then maybe even leaving the company together.

Handling referrals in the hiring process

Though a referral is a strong sign, itâs important to ensure that everybody goes through the same hiring process. If a candidate gets a softball interview, then the rest of the team may question whether they are truly qualified, which is not a good starting point.

Although all candidates should be treated respectfully during the hiring process, this is especially true for referrals. A bad hiring experience can seriously annoy the person who made the referral and discourage them from making any more in the future. If your hiring experience needs improvement across the board, consider focusing your efforts on referrals first and expanding from there. And donât forget to keep the referring employee up to date on the candidateâs status, which will help them feel included and encourage them to make more referrals.

Generating referrals

It is amazing how many referrals you can get if you just ask employees for them. Set yourself up to regularly communicate job openings and ask everyone on the team to refer qualified candidates. This can be handled by the recruiting team or by the manager (who could then use one-on-ones for referrals).

You should also decide whether to pay a bonus for successful referrals. Most companies do. Itâs a simple approach, and it works well. Consider the following points:

-

No referral bonus should be paid to managers who refer someone for their own team. Hiring for your own team is part of your job and shouldnât generate extra pay.

-

When considering how much to give as a referral fee, consider how much an external recruiter might charge. That dollar amount should be the upper limit. Most companies pay in the $2,000â$5,000 range.

-

Some companies (such as Amazon) have a progressive scale where the bonus gets larger for each referral generated. This can motivate employees to keep thinking of referrals and not stop after one or two, assuming that theyâve done their part.

Companies that donât offer bonuses often state that referrals are just part of the job, and employees should refer great colleagues so that they can work with the best people. One can imagine that a bonus might encourage someone to refer less qualified colleagues, but hopefully your interview process is rigorous enough to filter out those who arenât a good fit.

Applications

Applications are one of the most straightforward methods of finding new employees. Candidates simply apply directly to the company, mainly by using a form on the companyâs website. But this method is not effective for most small companies as they are unlikely to be known by many qualified applicants.

There are techniques that can help raise awareness of a new company, such as advertising on job boards or getting mentioned in the press. Another way is to publish blog posts about the companyâs social values or engineering culture. Besides being a positive thing to do, it attracts like-minded future staff. Stewart Butterfield, for example, sent a letter to all Slack employees urging them to take time to reflect on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day despite the fact that not all businesses observe it as a holiday.

The downside of applications is the high level of noiseâapplications that clearly are not a good fit for the advertised position. There is no easy remedy for this issue; reading CVs simply takes patience and time.

Sourcing

Sourcing is a proactive recruiting technique in which you search social networks, open source hosting sites like GitHub, or other relevant sites for potential candidates and then contact them directly. This can be done internally by dedicated recruiters or hiring managers, or externally by contractors, often called âhead hunters.â

In the beginning, sourcing might be handled by the founders or other senior leaders, with the task of scheduling interviews being handled by the office manager. This illustrates very nicely the two main roles in recruiting:

-

A recruiter does the actual sourcing work, approaching candidates through various methods.

-

A recruitment coordinator is responsible for organizing the candidate experienceâthat is, scheduling interviews, welcoming candidates, and making sure interviews happen as planned. Itâs easy to underestimate how much work this is.

The recruitment work can also be done by an external recruiter, which can get you access to a large, preexisting candidate pool. External recruiters tend to use one of these three approaches:

- Commission

- Depending on the market, an external recruiter might take 10%â25% of a new hireâs first-year salary as a commission. Usually, no up-front payment is required.

- Executive (fixed fee)

- An executive recruiter usually works for a fixed fee. The fee structure varies from firm to firm, but often they are paid in three installments, one at the beginning of the search, one when candidates start interviewing, and the last when a candidate they sourced is hired. Note that the first two payments are often required, even if you hire someone from a different source or decide to give the job to an internal candidate. Executive recruiters charge more than other recruiters, but their fee often gives you access to an exclusive candidate pool.

- By effort

- Alternatively, a recruiter may charge by the effort it takes to find candidates, usually just an hourly rate.

Table 1-1 shows the pros and cons of these approaches.

| Â | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Commission |

|

|

| Executive |

|

|

| By effort |

|

|

When selecting an external recruiter, we recommend the following:Â

-

Ask your network to refer you to recruiters theyâve used successfully in the past.

-

Check references; ideally, theyâve worked with companies that have a strong hiring process. A proven track record of unbiased (or less biased) hiring is important if you want to get diversity right.

-

Interview them on how they calibrate with hiring managers, as this can tell you how well the recruiter will be able to find appropriate candidates. A recruiter who doesnât understand what you need will have a hard time finding good people.

General recommendation

For roles with titles held by only one person, such as a VP of Product, it makes sense to hire an external recruiter, as there isnât likely an existing pipeline of candidates. If that position is relatively senior, consider using an executive recruiter. In other cases, use a recruiter who is working on commission or on an hourly basis. For positions you constantly recruit for, such as a Junior Programmer, we recommend building internal expertise.

Calibration between hiring manager and recruiter

The most important aspect of the relationship between a recruiter (external or internal) and the hiring manager is continuous calibration. This means that the recruiter and the hiring manager are in regular contact to review the requirements for potential hires. If these two people are misaligned, you are likely to waste effort interviewing and rejecting candidates that donât fit the role. You can tell you need to work on calibration if you hear from interviewers that the interviews they are doing are not worth their time, and the quality of candidates is not good enough.

To align the hiring manager and the recruiter, you can use a calibration exercise, in which the recruiter prepares a list of 10â20 hypothetical candidates with different backgrounds, seniority levels, and strengths and weaknesses. The hiring manager and the recruiter then spend approximately one hour together, during which the hiring manager screens the CVs and explains to the recruiter why certain CVs are interesting and others are not. Usually, this helps both sides tremendously; the hiring manager often gains a clearer understanding of what they are looking for, which helps the recruiter do a better job of searching for and filtering candidates. Executive recruiters commonly use this technique at the beginning of a search to get a clearer understanding of the ideal candidate.

The first calibration exercise (finding 10â20 candidates with different backgrounds) requires significant effort, but after itâs done, a weekly, in-person review of CVs by the recruiter and the hiring manager can efficiently keep them in sync. Instead of simply saying âyesâ or ânoâ for each candidate, the hiring manager should try to understand where the recruiter was coming from so the two are in agreement about which qualities are important and can adjust their expectations. Best is to have the recruiter explain: âI said ânoâ to this candidate because of X and Y, and I presented you this other candidate because I thought Z was interesting.â Over time, the recruiter will get a better sense of whatâs attractive to the hiring manager. We recommend taking this approach for every open position.

When to hire an internal recruiter

The right time to hire an internal recruiter depends on a couple of factors: how much time hiring managers are spending on recruitment work, and your overall recruiting strategy. Look for these warning signs:

-

The process of scheduling interviews, booking flights, and so on takes so much time that the team office assistant or a department lead spends most of their time arranging these details, and as a result ends up neglecting the tasks they were actually hired to do. Administrative arrangements like these can be delegated to a recruitment coordinator.

-

The same is true for screening calls. At one company, there was only one person in engineering screening CVs and doing the initial calls with candidates. This took more than half of their time. Only after the company hired a recruiter was the original person able to focus on other tasks. You can delegate these calls to engineers, but without proper calibration, it might not end well. A well-calibrated recruiter, who does most of the screening work, can help here.

One full-time recruiter typically hires one to two candidates each month for companies with rigorous hiring standards and adequate organizational support for the recruiting effort. Assuming the same rate applies to a hiring manager, you can calculate the time it takes for a hiring manager to be successful in recruiting. In the first stages of building a recruitment team, it is very important to focus on the quality of the recruiter, and to make sure the recruiter and hiring manager maintain a very close relationship.

The right time to hire a recruitment coordinator depends on how long the team assistant, executive assistant, or hiring manager can deal with the work associated. An experienced and talented first hire can often act as both recruiter and coordinator for some time.

Building an Employer Brand

You might think, âThere are so many things to doâwhy should I invest in an employer brand?â But a strong brand can help you tremendously with recruiting. High-quality candidates are often motivated to apply by insightful posts on the companyâs blog. It can also boost retention; when you give your employees the opportunity to promote their work, either through public posts or conference appearances, it helps them build their careers and feel recognized for their work.

Engineering/Product/Design Blog

If the nature of your business allows you to share internal stories, set up a blog to talk about them. Beyond the points just described, many candidates will read your posts to get an impression of your team culture, the technologies and methodologies you use, and so on. Just make sure you keep up a regular cadence of posts. A stale, outdated blog is a disadvantage when it comes to recruiting.

Meetups

Meetups are an easy way to connect to local candidates. If your office allows it, consider hosting meetups related to your business or to the technologies your team has chosen. The organizers are often very grateful for the space and will give you a few minutes to talk about your team and any relevant job openings. The costs of sponsoring meetups are very low compared to conferences and therefore a good way for smaller companies to gain some exposure. Finally, speaking at meetups about interesting things going on at your company can help motivate candidates to apply.

Speaking at Conferences

Speaking at conferences can give you a lot of publicity, assuming you choose the conferences wisely. Preparing a talk requires a lot of time, so letting your employees talk at irrelevant conferences makes no sense. Look for one of these two conditions before approving a conference talk:

-

Do potential candidates visit the conference, and is the topic of the attendeeâs talk likely to be interesting to them?

-

Are there talks or speakers the attendee can learn from?

In short, a conference has to be either a recruiting opportunity or a learning opportunity.

Open Source Contributions

Many engineers value the ability to contribute to open source software (OSS), especially if the company allows them to contribute during work time. But keep in mind the needs of your companyâs business before agreeing to open source your teamâs work. A reasonable policy is to encourage contributions during work time for OSS products used internally and to allow engineers to open source technologies that donât provide a competitive advantage. But keep in mind that an open source project requires ongoing maintenance and support. Simply dumping some code into a repository and then never updating it or accepting pull requests might end up damaging your engineering brand.

Conclusion

Hiring great people is essential to building a great team. In this chapter, weâve covered the key principles that underlie a scalable recruiting process, and the best ways of getting qualified candidates into your recruiting pipeline. The next step is to sort through the candidates, evaluate which ones best fit your needs, and make a hiring decision, all of which we will cover in Chapter 2, Scaling Hiring: Interviews and Hiring Decisions.

Additional Resources

-

Tammy Hanâs âA Primer for Startups and Job Seekers to BOTH Win the Talent Warâ gives advice to companies and candidates on how to make the right choices.

-

In âThoughts on Diversity Part 2. Why Diversity Is Difficultâ, Leslie Miley reflects on his time at Twitter and the problems faced while trying to build a more diverse workforce.

-

The Wikipedia entry for âDiversity (business)â gives a good overview of the business advantages of diversity.

-

Riley Newman and Elena Grewalâs âBeginning with OurselvesâUsing Data Science to Improve Diversity at Airbnbâ describes how Airbnbâs Data Science team improved diversity using some of the techniques they are using for customers.

1 Paul Petrone, âHere Is Why Employee Referrals Are the Best Way to Hireâ, LinkedIn Talent Blog, August 3, 2015, http://bit.ly/2hNYNxx.

2 This is discussed more fully in âWhy Employee Referrals Are the Best Source of Hireâ.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Kim-Mai Cutler, âWhat the Kapors Have Learned from Years of Working on Diversity in Techâ, TechCrunch, April 2, 2015.

Get Scaling Teams now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.