Although reading a book is a good way to learn the ins and outs of a program, nothing beats sitting in front of a computer and putting that program through its paces. Many of this book’s chapters, therefore, conclude with hands-on training: step-by-step tutorials that show you how to create a real, working, professionally designed website for a fictional café, Cafe Soylent Green.

The rest of this chapter introduces Dreamweaver by taking you step by step through the process of building a web page. It shouldn’t take more than an hour. When it’s over, you’ll have learned the basic steps for building any web page: creating and saving a new document, adding and formatting text, inserting graphics, adding links, and tapping the program’s site-management features.

If you already use Dreamweaver and want to jump right into the details of the program, feel free to skip this tutorial. (And if you’re the type who likes to read first and try second, read Chapter 2 through Chapter 5 and then return to this point to practice what you just learned.)

Note

The tutorial in this chapter requires the example files from this book’s website, http://www.sawmac.com/dwcs6/. Click the Download Tutorials link to save the files to your local drive. The tutorial files are in Zip format, a technology that compresses a lot of files into one, smaller archive file.

Windows folks should download the Zip file and then double-click it to open the archive. Click the Extract All Files option and then follow the instructions the Extraction Wizard gives you to store the files on your computer. Mac users can just double-click the file to decompress it.

After you download and decompress the Zip file, you should have an MM_DWCS6 folder on your computer, containing all the tutorial files for this book.

Before you start working in Dreamweaver, make sure the program’s set up to work for you. In the following steps, you’ll double-check some key Dreamweaver settings and organize your workspace using Dreamweaver’s Workspace Layout feature.

First, make sure your preferences are all set:

If it isn’t already open, start Dreamweaver.

Hey, you’ve got to start with the basics, right?

Choose Edit→Preferences (Windows) or Dreamweaver→Preferences (Macs).

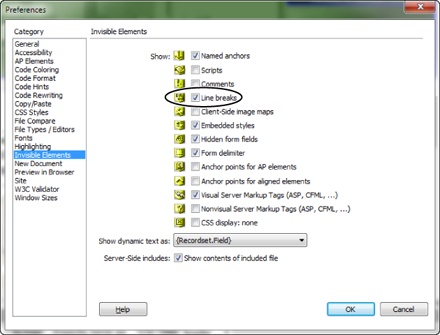

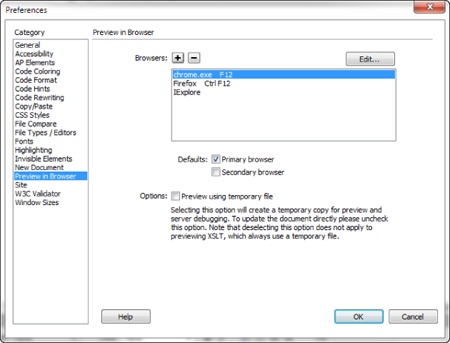

The Preferences dialog box opens, listing a dizzying array of categories and options (see Figure 1-19).

In the Preferences dialog box, select the Invisible Elements category and then turn on the fourth checkbox from the top, Line Breaks (circled in Figure 1-19).

Sometimes, when you paste text from other programs, like Microsoft Word or an email program, Dreamweaver displays what were once separate paragraphs as one long, single paragraph broken up with invisible characters called line breaks (for you HTML-savvy readers, this is the <br> tag). Normally, you can’t see the line break character in Dreamweaver’s Design view. This setting makes sure you can—it represents breaks in the document window using a little gold shield. The shield gives you an easy way to select a line break and remove it to create a single paragraph by combing the text before and after the line break, or to create two paragraphs.

Click OK.

The Preferences dialog box closes. You’re ready to get your workspace in order. As noted at the beginning of this chapter, Dreamweaver offers many windows to help you build web pages. For this tutorial, though, you need only three: the Insert panel, the document window, and the Property Inspector. But, for good measure (and to give you a bit of practice), you’ll open another panel and rearrange the workspace a little. To get started, have Dreamweaver display the space-saving Classic workspace.

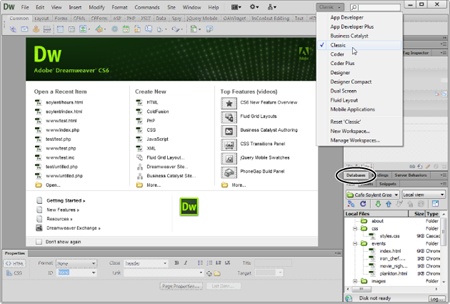

From the Workspace Switcher on the Application bar, select Classic (see Figure 1-20), or go to Window→Workspace Layout from the main menu and then select Classic from the drop-down list.

If you see Classic already selected, choose Reset ‘Classic,’ which moves any panels that were resized, closed, or repositioned back to their original locations. The Classic workspace puts the Property Inspector at the bottom of the screen, turns the Insert panel into an Insert toolbar that appears directly below the Application bar, opens the CSS Styles and Files panels on the right edge, and displays other closed tabs (for Adobe BrowserLab and a group of tabs for working with server-side programming and databases).

Figure 1-20. The Dreamweaver Welcome screen pictured in the middle of this figure lists recently opened files in the left column. Clicking one of the file names opens that file for editing. The middle column provides a quick way to create a new web page or define a new site. In addition, you can access introductory videos and other getting-started material from the screen’s right-hand panel. You see the Welcome screen only when you have no other web files open.

Adobe BrowserLab, discussed on Previewing Web Pages in BrowserLab, provides a quick way to see what your web page will look like in different browsers on both Windows and Mac PCs. You won’t be needing the server-side tabs (Databases, Bindings, and Server Behaviors); Dreamweaver uses them with its outdated server-side tools, so you’re best off avoiding them. Fortunately, you can close a group of tabs to get them out of the way.

Right-click (Control-click) the Databases tab (circled in Figure 1-20), and choose Close Tab Group from the drop-down menu.

The Databases panel and its two other tabs disappear (you can always get them back by selecting Window→Databases).

The CSS Styles panel is very useful; it also comprises three panes stacked one on top of the next, so giving it plenty of vertical room is a good idea.

Drag the thick line that appears between the top of the Files panel and the bottom of the CSS Styles panel (circled in Figure 1-21) down until the Files panel is about half the size of the CSS Styles panel.

Now the workspace looks great. It displays most of the panels you need for this tutorial (and for much of your web page building). Since this arrangement is so useful, you’ll want to save it as a custom layout (OK, maybe you don’t, but play along).

Figure 1-21. Make a panel taller or shorter by dragging the thick line separating two panels (circled). The options in some panels, like the CSS Styles panel here, are dimmed if you don’t have a web page open. You can also minimize a panel group by double-clicking its tab. For example, double-clicking the Files tab in this figure hides the Files panel (the list of files) and expands the CSS Styles panel—a good technique if you need more space for a particular panel. To re-open a closed panel, just click its tab once.

From the Application bar’s Workspace Switcher, choose New Workspace.

The Save Workspace window appears, waiting for you to name your new layout.

Type Missing Manual (or any name you like), and then click OK.

You just created a new workspace layout. To see if it works, switch to another one of Dreamweaver’s layouts, see how the screen changes, and then switch back to your new setup.

From the Workspace Switcher, choose App Developer Plus.

This moves the panels around quite a bit, and even displays some panels in Dreamweaver’s iconic mode (described on Iconic Panes). This layout is a bit too complicated for your needs, so you’ll switch back.

From the Workspace Switcher, choose Missing Manual (or whatever you named your custom space in step 9).

Voilà! Dreamweaver resets everything the way you had it before. You can create multiple workspaces for different websites or different types of sites.

As discussed on Setting Up a Site, whenever you use Dreamweaver to create or edit a website, your first step should always be to show Dreamweaver the location of your local site folder (also called the local root folder)—the master folder for all your website’s files. You do this by setting up a site, like so:

Choose Site→New Site.

The Site Setup window appears. You only need to provide two pieces of information to get started.

Type Test Drive in the Site Name field.

The name you type here is solely for your own reference; it lets you identify the site in Dreamweaver’s Site menu. Dreamweaver also asks where you want to store the website’s files. In this example, you’ll use one of the folders you downloaded from this book’s website (at other times, you’ll choose or create a folder of your own).

Click the folder icon next to the label “Local site folder.”

The Choose Root Folder window opens so you can navigate to a folder on your hard drive to serve as your local folder. (This is the folder on your computer where you’ll store the HTML documents and graphics, CSS, and other web files that make up your site.)

Browse to and select the Chapter01 folder located inside the MM_DWCS6 folder you downloaded earlier. Click the Select (Choose) button to set this folder as the local root folder.

At this point, you’ve given Dreamweaver all the information it needs to successfully work with the tutorial files.

Click Save to close the Site Setup window.

After you set up a site, Dreamweaver creates a site cache for it (see Creating a Web Page). Since there are hardly any files in the Chapter01 folder, you may not even notice this happening—it goes by in the blink of an eye.

“Enough already! I want to build a web page,” you’re probably saying. You’ll do just that now:

Choose File→New.

The New Document window opens. Creating a blank web page involves a few clicks.

From the left-hand list of document categories, select Blank Page; in the Page Type list, highlight HTML; and from the Layout list, choose <none>. From the DocType menu in the bottom-right, select HTML 5.

As discussed on Document Types, HTML comes in a variety of flavors, called doctypes. HTML5 is the latest and greatest version, so use it.

Click Create.

Dreamweaver opens a new, blank HTML page. Even though the underlying code for an HTML page differs in slight ways depending on which document type you chose (HTML 4.01 Transitional, XHTML 1.0 Strict, HTML5, and so on), you have nothing to worry about: When you add HTML in Design view, Dreamweaver writes the correct code for your doctype.

If you see a bunch of strange text in the document window, you’re looking at the underlying HTML, and you’re in either Code or Split view. If your monitor is wide enough to view both the Code and Design views side-by-side, select the Split button at the top of the document window; if your monitor is on the small side, click Design. (If you don’t see these buttons, choose View→Toolbars→Document.) You’ll work mainly in the visual Design view for this tutorial.

Choose File→Save.

The Save As dialog box opens.

Always save a newly created page right away. This good habit prevents serious headaches if the power goes out as you finish that beautiful—but unsaved—creation.

Save the page in the Chapter01 folder as index.html.

You could also save the page as index.htm; both .html and .htm are valid extensions for HTML files. On most web servers, you’ll name the home page index.html (see the box on All Those Index Pages for an explanation).

Make sure you save this page in the correct folder. In Phase 2 (Phase 2: Creating a Website), you told Dreamweaver to use the Chapter01 as the site’s root folder—the folder that holds all the pages and files for the site. If you save the page in a folder outside of Chapter01, Dreamweaver gets confused and its site-management features won’t work correctly.

If the document window toolbar isn’t already open, choose View→Toolbars→Document to display it.

The toolbar at the top of the document window provides easy access to a variety of tasks you’ll perform frequently, such as titling a page, previewing it in a web browser, and looking at the HTML.

In the toolbar’s Title field, select the text “Untitled Document,” and then type in “Welcome to Cafe Soylent Green.”

The Title field lets you set a page’s title—the information that appears in the title bar of a web browser. The title also shows up as the name of your page when someone searches the web using a search engine like Google or Bing. In addition, a clear and descriptive title that identifies the main point of the page can also help increase a page’s rank among the major search engines.

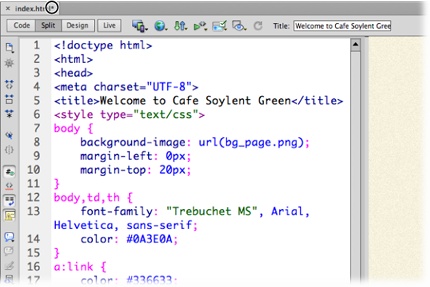

If you have Split view turned on, you’ll notice that in Code view, Dreamweaver updated the <title> tag in the HTML to read “<title>Welcome to Cafe Soylent Green</title>.”

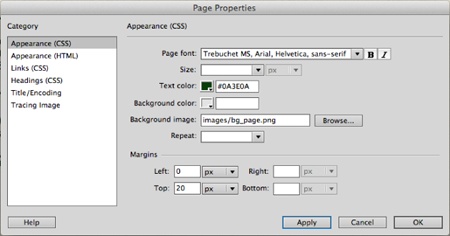

In the Property Inspector, click the Page Properties button, or choose Modify→Page Properties.

The Page Properties dialog box opens (see Figure 1-22), letting you define the basic look of each web page you create. Six categories of settings control attributes like text color, background color, link colors, and page margins.

From the “Page font” menu, select “Trebuchet MS, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif.”

This sets a basic font (and three backup fonts, in case your visitor’s machine lacks Trebuchet MS) that Dreamweaver automatically uses for all the text on the page. However, as you’ll see later in this tutorial, you can always specify a different font for selected text.

Next to “Text color,” click the small gray box. From the pop-up color palette, choose a color (a dark green color works well with this site).

Unless you intervene, all web page text starts out black; the text on this page reflects the color you select here. In the next step, you’ll add an image as a background to liven up the page.

Note

Alternatively, you could type a color value, like #333333, into the field beside the palette icon. That’s hexadecimal notation, which is familiar to HTML coding gurus. Both the pop-up color palette and the hexadecimal color-specifying field appear fairly often in Dreamweaver. Dreamweaver CS6 even lets you specify a color using other values, such as RGB (red-green-blue) and HSL (hue-saturation-lightness) values. See Adding Bold and Italic for more on setting colors in Dreamweaver.

To the right of the “Background image” field, click the Browse button.

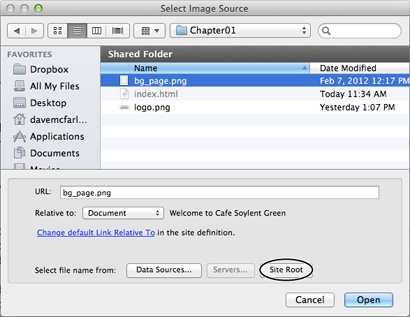

The Select Image Source window appears (see Figure 1-23). Use it to navigate to and select a graphic.

Figure 1-23. Use the Select Image Source window to insert graphics on a web page. The Site Root button (circled) is a shortcut to your local site’s main, or root, folder—a nifty way to quickly get to your root folder when you search for a file. On Windows, the Site Root button appears at the top of the window.

Click the Site Root button at the top of the window (bottom of the window on Macs). Select the file bg_page.png, and then click OK (Open).

In Dreamweaver, you can select a file and close the selection window just by double-clicking the file name.

Note

Windows Users: Normally, Windows doesn’t display a file’s extension. So when you navigate to the images folder in step 13 above, you might see bg_page instead of bg_page.png. Since file extensions are an important way people (and web servers) identify the types of files a website uses, you probably want Windows to display extensions. Here’s how you do that: In Windows Explorer, navigate to and select the MM_DWCS6 folder. If you use Windows 7 or Vista, choose Organize→“Folder and search options.” If you use Windows XP, choose Tools→Folder Options. In the Folder Options window, select the View tab, and then turn off the “Hide extensions for known file types” checkbox. To apply this setting to the tutorial files, click OK; to apply it to all the files on your computer, click the “Apply to Folders” button, and then click OK.

In the Left margin field, type 0; in the Top margin field type 20.

The 0 setting for the left margin removes the little bit of space web browsers insert between the contents of your web page and the left side of the browser window. The 20 adds 20 pixels between the top of the browser window and the page contents.

If you like, you can change this setting to make the browser add more space to the top and left side of the page, or set both values to 0 to remove any space between the page’s content and the browser window edges. In fact, you can even add a little extra empty space on the right side of a page. (The right margin control is especially useful for languages that read from right to left, like Hebrew or Arabic.)

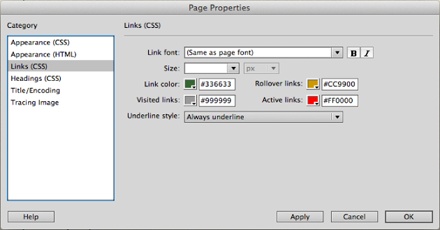

Back in the Category menu (far left of the Page Properties window), click Links, and then add the following properties: In the “Link color” field, type #336633 ; in the “Visited links” field, type #999999 ; in the “Rollover links” field, type #CC9900 ; and in the “Active links” field, type #FF0000 (see Figure 1-24).

These hexadecimal codes specify web page colors (see Picking a Font Color on page 157 for more on choosing colors for web pages).

Figure 1-24. You can set several hyperlink properties using the Links category of the Page Properties dialog box. You can choose a different font and size for links, as well as specify colors for four different link states. Finally, you can choose whether (or when) a browser underlines links. Most browsers automatically do, but you can override that behavior with the help of this dialog box and the Cascading Style Sheet Dreamweaver creates.

Links come in four varieties: regular, visited, active, and rollover. A regular link is a plain old link, unvisited, untouched. A visited link is one you’ve already clicked, as noted in your browser’s History list. An active link is one you’re currently clicking (you’re pressing the mouse button down as you hover over the link). And finally, a rollover link indicates what the link looks like when you mouse over it without clicking. You can choose different colors for each of these link states.

While it may seem like overkill to have four different colors for links, the regular and visited link colors provide useful feedback to web visitors by telling them which links they’ve already followed and which remain to be checked out. For its part, the rollover link gives you instant feedback, changing color as soon as you move your cursor over it. The active link color isn’t that useful for navigating a site since its color changes so briefly you probably won’t even notice it.

Click OK to close the window and apply the changes to the page.

If you look at the top of the document window, you’ll see an asterisk next to the file name—that’s Dreamweaver’s way of telling you that you haven’t saved a page you edited, a nice reminder to save your file frequently and prevent heartache if the program suddenly shuts down (see circled image in Figure 1-25).

Figure 1-25. An asterisk next to a file name (circled) means you’ve made changes to the file, but haven’t yet saved it—quick, hit Ctrl+S (⌘-S)!

If you’ve been working in Split view, you’ll also notice that Dreamweaver added the HTML <style> tag with some other code inside it—this is called a CSS style sheet and the code includes formatting information that dictates how a browser displays various tags (you’ll learn all about this in Chapter 3.)

Choose File→Save (or press Ctrl+S [⌘-S]).

Save your work frequently. (This isn’t a web technique so much as a computer-always-crashes-when-you-least-expect-it technique.)

Now you’ll add the real meat of your web page, words and pictures.

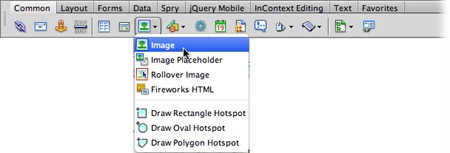

On the Insert bar’s Common tab, from the Image menu, select Image (see Figure 1-26).

Alternatively, choose Insert→Image. Either way, the Select Image Source dialog box opens. (If you didn’t choose the Classic view from the Workspace Switcher—step 5 on Phase 1: Getting Dreamweaver in Shape—then the Insert bar is really the Insert panel and it appears in the right-hand group of panels.)

Figure 1-26. Some of the buttons on Dreamweaver’s Insert toolbar do double duty as menus (the ones with the small, black, down-pointing arrows). Once you select an option from the menu (in this case, the Image object), it becomes the button’s current setting. If you want to insert the same type of object again, you don’t need to use the menu—just click the button.

Make sure you’re in the local root folder and double-click the logo.png graphics file.

The Image Tag Accessibility window opens. Fresh out of the box and onto your computer, Dreamweaver automatically turns on several accessibility preferences. They’re designed to make your pages more accessible to people who use alternative devices for viewing websites—for example, people with viewing disabilities who require special web browser software, such as a screen reader,which reads the contents of a web page out loud. Of course, images aren’t words, so they can’t be spoken. But you can describe an image by adding what’s called an alt property. This is a text description of the graphic (an alternative to seeing the image) that’s useful not only for screen-reading software, but for people who deliberately turn off pictures in their web browser so pages load faster. (Search engines also look at alt properties when they index a page, so an accurate description can help your site’s search-engine rankings.)

In the “Alternate text” field, type Cafe Soylent Green. Click OK to add the image to the page.

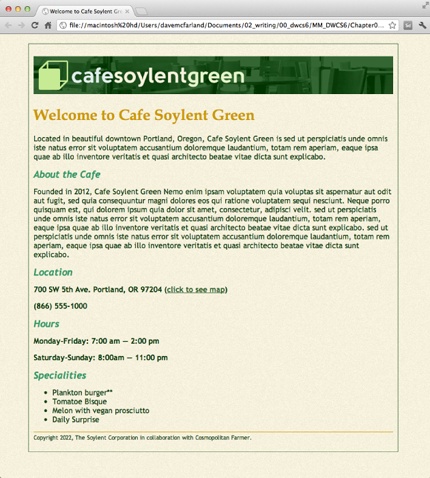

The café’s banner appears at the top of the page, as shown in Figure 1-27. A thin border appears around the image, indicating that you have it selected. Note that the Property Inspector changes to reflect the properties of the selected item, the image in this case.

Figure 1-27. When you select an image in the document window, the Property Inspector reveals the image’s dimensions. In the top-left corner of the Inspector, a thumbnail of the image appears, as does the word “Image” (to identify the type of element you selected), and the image’s file size (in this case, 16 KB). You’ll learn about other image properties in Chapter 5.

Deselect the image by clicking anywhere else in the document window or by pressing the right arrow key.

Keep your keyboard’s arrow keys in mind—they’re a great way to deselect a page element and move your cursor into place to add text or more images.

Press Enter (Return) to create a new paragraph. Type Welcome to Cafe Soylent Green.

Make sure you’re in Design view here—pressing Enter (Return) in Code view simply inserts a carriage return and no paragraph tags. Notice that the text is a dark color and uses the Trebuchet (or, if you don’t have Trebuchet MS installed, the Arial) font; you set these options earlier, in the Page Properties dialog box. The Property Inspector now displays text-formatting options.

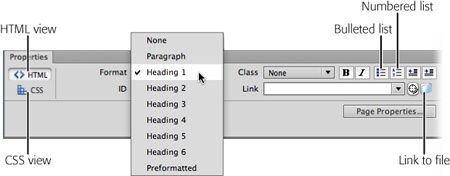

In the Property Inspector, click the HTML button and then, from the Format menu, choose Heading 1 (see Figure 1-28).

The text you just typed becomes big and bold—the default style for Heading 1. The Format menu offers a number of paragraph types. Right now, the text doesn’t stand out enough, so you’ll change its color.

Figure 1-28. The Property Inspector includes two views: HTML and CSS. The HTML view, shown here, lets you control the HTML tags Dreamweaver applies to text: bulleted lists, paragraphs, links, and so on. The CSS view provides a simple interface for creating CSS styles so you can format text to look great.

Select the text you just typed.

You can do so either by dragging carefully across the entire line or by triple-clicking anywhere inside the line. (Unlike the Format menu, which affects an entire paragraph at a time, many options in the Property Inspector—like the one you’ll use next—apply only to text you’ve selected.)

In the Property Inspector, click the CSS button to switch to CSS properties. From the “Targeted rule” menu, choose New CSS Rule. In the Color field of the Property Inspector, replace the value that’s listed with #CC9900 (or select a color using the color box, if you prefer), and then hit Enter (Return).

The New CSS Rule window opens. This window (which you’ll learn a lot more about in Chapter 3) lets you create new CSS styles. In this case, you’ll create a type of style, called a tag style, that Dreamweaver applies to any Heading 1 (<h1> tag) on a page.

From the top menu, select “Tag (redefines an HTML element).”

Notice that the field below that menu changes to display “h1.” This is called a selector—and once you define its characteristics, it tells web browsers how to display any level-1 heading (in other words, any text that has an <h1> tag applied to it).

Don’t worry about any of the other settings in this window; you’ll learn the details soon.

Click OK.

Dreamweaver has just created a new CSS style. Now, wasn’t that easy? Next, you’ll change the font for this text.

Make sure you still have the headline selected. In the Property Inspector, choose “Palatino Linotype, Book Antiqua, Palatino, serif” from the Font menu.

This time, Dreamweaver doesn’t open the New CSS Rule window; that’s because you’re simply adding more styling information to the style you created in step 9. Now the heading will have the color you specified in step 8 and the font you chose in this step.

Time to add more text.

Click to the right of the heading text to deselect it. Press Enter (Return) to create a new paragraph below the headline.

Although you may type a headline now and again, you’ll probably get most of your text from word processing documents or emails from your clients, boss, or coworkers. To get that text into Dreamweaver, you simply copy it from the document and paste it into your web page.

In the Files panel, double-click the file home-page.txt to open it.

This file is just plain text—no formatting, just words. To get it into your document, you’ll copy and paste it.

Click anywhere inside the text, and then choose Edit→Select All, followed by Edit→Copy. Click the index.html tab to return to your web page and, finally, choose Edit→Paste.

You should see a few gold shields sprinkled among the text (circled in Figure 1-29). If you don’t, make sure you completed step 3 on Phase 1: Getting Dreamweaver in Shape. These shields represent line breaks—spots where text drops to the next line without creating a new paragraph. You’ll often see these in pasted text. In this case, you need to remove them, and then create separate paragraphs.

Click one of the gold shields and then press Enter (Return). Repeat this for all the other gold shields in the document window.

This deletes the line break in the document (it actually deletes the HTML tag <br>) and creates two paragraphs out of one.

At this point, the pasted text is just a series of paragraphs. To give it some structure, you’ll add headings and a bulleted list.

Click in the paragraph with the text “About the Cafe.” In the Property Inspector, click the HTML button, and then choose Heading 2 from the Format menu.

That changes the paragraph to a headline, making it bigger and bolder.

Repeat the last step for the lines of text “Location,” “Hours,” and “Specialties” (near the end of the page).

You now have one Heading 1 and four Heading 2 headlines. The Heading 2 headlines could use a little style also.

Triple-click the headline “About the Cafe” to select it. In the Property Inspector, click the CSS button. In the Size field, delete “none”, and type 20.

The New CSS Rule window appears again. Now you’ll create a style for <h2> tags.

From the top menu, select “Tag (redefines an HTML element).”

You should see h2 in the middle field.

Click OK.

Notice that the text gets a little smaller—the style you just created applies to all <h2> tags, and they now share the same font size, 20 pixels. Next, you’ll change the text’s color.

Make sure you still have the headline selected and, in the Property Inspector, click in the field next to the color box, and replace the color currently there with #339966.

You’ve changed the color to a lighter and brighter shade of green.

In the Property Inspector, click the I (for italics) button.

This italicizes the text and updates the h2 style you created earlier—that’s why the other Heading 2 headlines are now italicized, too.

Select the four paragraphs under the headline “Specialties”; drag from the start of the first paragraph to the end of the fourth paragraph.

You can also drag up starting from the end of the last paragraph. Either way, you select all four paragraphs listing the café’s specialties.

In the Property Inspector, click the HTML button, and then click the Unordered (bulleted) List button (see Figure 1-28).

The paragraphs turn into a bulleted list of items, called an “unordered list” in HTML-speak. Finally, you’ll highlight location and hours.

Select the two paragraphs below the Location headline (beginning with 700 SW 5th and ending with the phone number).

You’ll make the address bold.

Make sure you have the HTML button pressed in the Property Inspector, and then click the B button.

The text changes appearance but the New CSS Rule window doesn’t appear. Even though you find the B (for bold) button on both the HTML and CSS views of the Property Inspector, they do different things. When you select it in HTML mode, Dreamweaver inserts the HTML <strong> tag—used to “strongly” emphasize text. But when you press the B button in CSS mode, Dreamweaver adds CSS code to the page to make the text look bold. It’s a subtle but important difference—in HTML mode, you change the formatting of just the selected text, but in CSS mode, you’d create a style, and that style would change the formatting of all the text that shared the same tag, the paragraph tag (<p>) in this example. (You’ll read more about this on Creating a Style with the Property Inspector.) In this case, you want to use the HTML <strong> tag to emphasize the selected text.

Repeat step 26 for the two paragraphs below the Hours headline, and then save the page.

You’ll add a few more design touches to the page, but first you should see how the page looks in a real web browser.

Dreamweaver’s Design view gives you a visual way to add and edit HTML. However, its display is frequently a long way off from that of a real web browser. Dreamweaver may display more information than you’d see on the Web (including “invisible” objects, like table borders and those line breaks you removed earlier), or it may display less (it sometimes has trouble rendering complex designs).

Furthermore, much to the eternal woe of web designers, different browsers display pages differently. Pages you view in Internet Explorer don’t always look the same in other browsers, like Firefox or Safari. In some cases, the differences may be subtle (for example, text may be slightly larger or smaller). In other cases, the changes can be dramatic: Earlier versions of Internet Explorer, for example, can’t display the text or box drop shadows discussed on Common CSS3 Properties.

Note

If you don’t happen to have a Windows computer, a Mac, and every browser ever made, you can take advantage of Adobe’s BrowserLab service, which takes screenshots of your page in a variety of browsers running on a variety of operating systems. You’ll learn about BrowserLab on Previewing Web Pages in BrowserLab.

If you’re designing web pages for a company intranet and only have to worry about the one web browser your IT department puts on everyone’s computer, you’re lucky. Most people have to deal with the fact that their sites must withstand scrutiny from a wide range of browsers, so it’s a good idea to preview your pages using whatever browsers you expect your visitors to use. Fortunately, Dreamweaver lets you preview a web page using any browser you have installed on your computer.

Note

With the increasing popularity of tablets and mobile phones, you can no longer just worry about how your web pages look in desktop browsers; you also have to think about how they look on the small screens of an iPhone, Android phone, or Windows phone. Chapter 11 has information on how Dreamweaver CS6 can help you make your websites mobile-ready.

One quick way to check a page in a web browser is to use Dreamweaver’s built-in Live view, which lets you preview a page using a browser that’s built into Dreamweaver.

In the Document toolbar, click the Live button (circled in Figure 1-30).

The Live button highlights. The page doesn’t look that different—for a simple page like this it won’t, but Live view is great for previewing more complex CSS and for testing JavaScript interactivity, like the kind Dreamweaver’s Spry tools, such as the Spry Menu Bar provide (Creating a Navigation Menu).

Figure 1-30. Dreamweaver’s Live view lets you preview a page in a real web browser, one built into Dreamweaver.

There is one problem with Live view: It uses WebKit, the engine behind Apple’s Safari browser and Google’s Chrome browser. This isn’t the only browser out there, so it’s not how all visitors will view your site. You want to test your page designs in other browsers, too. Fortunately, Dreamweaver makes it easy to jump straight to any web browser installed on your computer.

Click the Live button again to exit Live view.

This is an important and easily overlooked step. When you’re in Live view, you can’t edit a page in Design view. Since a page in Live view can look very much like it does in Design view, it’s easy to try to work on the page while you’re in Live view and say “Hey, what’s going on? Dreamweaver isn’t working any more!” So always remember to exit Live view when it’s time to work on your pages.

To preview your page in a web browser, you need to make sure Dreamweaver knows which browsers you have installed and where they are.

Tip

While you can’t edit a page in Design view while Live view is on, you can edit the HTML code in Code view. One common technique among HTML jockeys is to display Split view, and then turn on Live view. This opens the HTML code on the left and a live browser display on the right. They then merrily edit the HTML and view the changes in Live view. However, to see the effect of any changes you make in Code view, you need to click into the Live view area or press F5.

Choose File→“Preview in Browser”→Edit Browser List.

The “Preview in Browser” preferences window opens (see Figure 1-31). When you install Dreamweaver, it detects the browsers on your computer; a list of them appears in this window. If you installed a browser after you installed Dreamweaver, it doesn’t appear here, and you need to follow steps 4 and 5 next; otherwise, skip to step 6.

The Add Browser or Select Browser window opens.

Click the Browse button. Search your hard drive to find the browser you want to add to the list.

Dreamweaver inserts the browser’s default name in the Name field. If you wish to change it for display purposes within Dreamweaver, select it, and then type in a new name. (But don’t do this before you select the browser, since Dreamweaver erases anything you typed as soon as you select a browser.)

In the window’s Browser list, select the browser you most commonly use. Turn on the Primary Browser checkbox. Click OK.

You just designated this browser as the primary one when you work in Dreamweaver. You can now preview your pages in this browser with a simple keyboard shortcut: F12 (Option-F12 on a Mac). (Macintosh fans: Unfortunately, Apple has assigned the F12 key to the Dashboard program, so it takes two keys to preview the page—Option and F12 together; you can change this by creating your own keyboard shortcut, as described on Keyboard Shortcuts. If you’re using a Macintosh laptop, you may have to press Option-F12 and the function [fn] key in the lower-left corner of the keyboard.)

If you like, you can choose a secondary browser, which you launch by pressing Ctrl+F12 (⌘-F12) key combination.

Now you’re ready to preview your document in your favorite browser. Fortunately, Dreamweaver makes it easy.

Note

Windows PCs don’t list Google Chrome in the Program Files directory, as they do most other programs. Depending on your version of Windows, you’ll find Chrome in one of these locations:

Windows 7: C:\Users\Username\AppData\Local\Google

Vista: C:\Users\UserName\AppDataLocal\Google\Chrome

XP: C:\Documents and Settings\UserName\Local Settings\Application Data\Google\Chrome

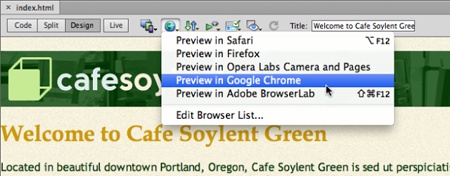

Press the F12 key (Option-F12), or choose File→“Preview in Browser” and then, from the menu, select a browser.

The F12 key (Option-F12) is the most important keyboard shortcut you’ll learn; it opens the web page in your primary browser so you can preview your work.

You can also use the “Preview in Browser” menu (the globe icon) in the document window to preview a page (see Figure 1-32).

Note

If you use the “Preview in Browser” menu to select a browser, you’ll notice one other option: “Preview in Adobe BrowserLab.” BrowserLab is an online service that takes screenshots of your web page using different browsers on both Windows and Mac machines—it’s a great way to make sure your design works in as many browsers as possible. You’ll learn about BrowserLab in depth on Previewing Web Pages in BrowserLab.

When you finish previewing the page, go back to Dreamweaver.

Do so using your favorite way to switch programs on your computer—by using the Windows taskbar or the Dock in Mac OS X.

You’ve covered most of the steps you need to finish this web page. Now you just need to add a graphic, format the copyright notice, and provide a little more structure to the page.

Scroll to the bottom of the page and select all the text in the copyright paragraph.

You can either triple-click inside the paragraph or drag from beginning to end.

Click the CSS button in the Property Inspector and then, from the Size menu, choose 12.

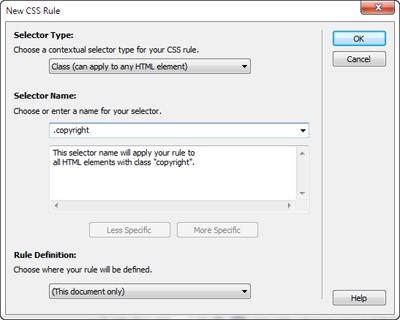

The New CSS Rule window opens again. This time you want to create a style that applies only to this paragraph of text—not every paragraph—so you need to use what’s called a class style.

Leave the default setting—“Class (can apply to any HTML element)”—for the Selector Type field, type .copyright in the Selector Name field (Figure 1-33), and then click OK.

Class names begin with a period—that’s how browsers identify the CSS style as a class. You can see that the copyright text gets smaller when you apply the .copyright class, which specifies a type size of 12 pixels.

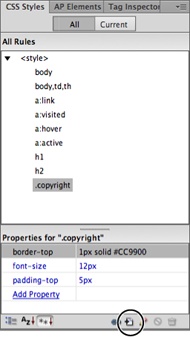

Another way to separate the copyright notice from the page’s main content is to add a simple line above it. CSS lets you do that with a property called Border; however, you can’t set that property using the Property Inspector; you need to use the CSS Styles panel.

Figure 1-33. The New CSS Rule window lets you create CSS styles. You can choose among many types of styles. In this case, you’re creating a class style named .copyright. Class styles work a lot like styles in word processors—to use them, you select the text you want to format, and then apply the style.

If it isn’t already open, open the CSS Styles panel by choosing Window→CSS Styles.

The CSS styles panel is the command center for working with style sheets (see Figure 1-34). It lists all the styles available to the current web page and lets you edit them and add new styles. You’ll learn all about it in Chapter 3, but for now you’ll get a taste of using it to edit a style.

Click the + (flippy triangle on Macs) button to the left <style> to display the list of styles on this page. Double-click the style .copyright at the bottom of the list of styles.

The CSS Rule Definition window opens (see Figure 1-35). This window lets you set dozens of CSS properties, including controls for formatting text, adding borders, and positioning elements on a page. You’ll learn about these properties throughout this book, but for now you’ll look at a couple of properties categories.

Figure 1-34. The CSS Styles panel has two views: All and Current. The All view, pictured here, lists all the styles available to the current page. You can edit a style by double-clicking its name, or add a new style by clicking the New Rule button (circled). You’ll learn about the Current view on page 393.

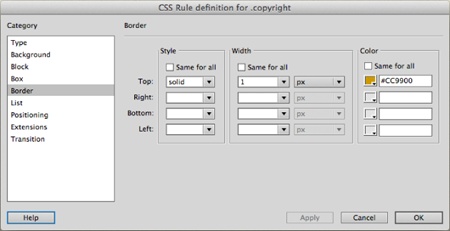

Click Border in the left-hand list of categories. Turn off the three “Same for all” checkboxes along the top and choose “solid” for the Top style, type 1 for the top width, and #CC9900 for the top color.

The window should now look like Figure 1-35. Borderlines touch the content of the element they surround—in other words, this top line sits very close to the copyright text. It’ll look better if there’s a bit of space between it and the copyright notice.

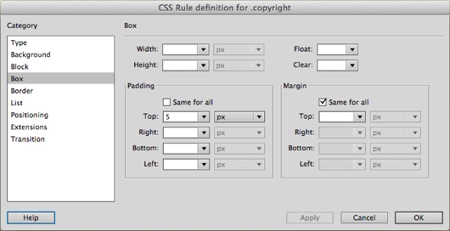

In the CSS Rule Definition window, click the Box category. Under the Padding settings, turn off the “Same for all” checkbox, type 5 in the Top field, and then click OK.

Padding is the space that appears between an element’s content (like the text in a paragraph or the graphic in the image tag). Adding padding increases the space between the border and the content. The window should now look like Figure 1-36.

Click OK to finish editing the style.

You’ll now see a brownish line above the copyright notice, nicely setting it off from the rest of the page. Next, you’ll link to a map that shows the location of the restaurant.

In the middle of the page, select the parenthetical text “click to see map.”

To create a link, you just need to tell Dreamweaver which page you want to link to. You can do this several ways. Using the Property Inspector is the easiest.

In the Property Inspector, click the HTML button, and then click the folder icon that appears to the right of the Link field.

The Select File dialog box appears.

Click the Site Root button (at the top of the dialog box in Windows, the bottom of the dialog box on Macs), and double-click the file map.html.

The Site Root button jumps you right to the folder containing your site. It’s a convenient way to move quickly to your root folder. Double-clicking the file name tells Dreamweaver to insert the HTML needed to create a link along with the link’s address.

If you save the page and then preview it in a web browser, click the link you just added. The browser jumps to another page (one already created for you). You’ll notice that there’s text near the bottom of the map that reads “back to home page.” Since you just learned the powerful link-adding skill, open map.html and add a link to that page. Select the text “back to home page” and link to the index.html file by following steps 10 and 11, and then save the map.html file. We’ll wait for you….

You may have noticed that the map page’s content is contained in a box that’s nicely centered in the middle of the screen. That would look great on the home page you’ve created as well. You’ll create a new layout element to achieve this effect.

Return to the index.html file; click anywhere inside the page, and then choose Edit→Select All or press Ctrl+A (→-A).

You selected the entire contents of the page. You’ll wrap all the text and images in a <div> tag to create a kind of container for the page contents.

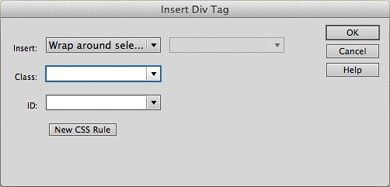

Choose Insert→Layout Objects→Div Tag.

The Insert Div Tag window opens (see Figure 1-37). A <div> tag simply provides a way to organize content on a page by grouping HTML—think of it as a box containing other HTML tags. For example, to create a sidebar that includes navigation links, news headlines, and Google ads, you’d wrap them all in a <div> tag. It’s a very important tag for CSS-based layouts. You’ll read more about it on Float Layout Basics.

Figure 1-37. The Insert Div Tag window provides an easy way to divide sections of a web page into groups of related HTML—like the elements (graphic, navigation bar, and so on) that make up a page banner, for example. You’ll learn about all the different functions of this window on page 440.

Next, you need to create a style that provides the instructions that format this new <div> tag. You’ve already used the Property Inspector to create a style, but that works only for text. To format other tags, you need to create a style in another way.

Click the New CSS Rule button at the bottom of the Insert Div Tag window.

The New CSS Rule window appears (a CSS style is technically called a “rule”). This window lets you specify the type of style you create, the style’s name, and where Dreamweaver should store the style information. You’ll learn all the ins and outs of this window in Chapter 3.

From the top menu, choose “Class (can apply to any HTML element),” and then type .container in the “Choose or enter a name” field. Make sure you have “This document only” selected in the bottom menu. Click OK.

The “CSS Rule definition” window appears. (There’s a lot going on in this box, but don’t worry about the details at this point. You’ll learn everything there is to know about creating styles later in this book. This part of the tutorial is intended to give you a taste for some of a web designer’s daily page-building duties. So relax and follow along.) First, you’ll add a border around the edges.

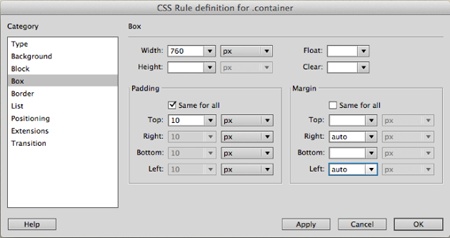

From the left-hand list of categories, select Border. Leave the three “Same for all” checkboxes turned on, and choose “solid” for the style, type 1 for the width, and then type #336633 for the color.

This action adds a green border around the edges. Next, you’ll give the div tag a set width and center it on the page.

Click the Box category, and then, in the width field, type 760.

This makes the box 760 pixels wide—the same width as the banner. To make sure the text doesn’t butt right up against the edge of the box, you’ll add a little padding around the inside of this style.

Make sure the “Same for all” checkbox is turned on, and then type 10 in the Top field under Padding.

This adds 10 pixels of space inside the box, essentially pushing the text and the graphics away from the edges of it.

Under the Margin settings, turn off the “Same for all” checkbox, and then, for both the right and left margin menus, select “auto.”

The window should now look like Figure 1-38. Selecting “auto” for the left and right margins is your way of telling a web browser to automatically supply values for those margins—in this case, as you’ll see in a moment, it has the effect of centering the <div> element in the middle of a browser window.

Click OK to complete the style.

The Insert Div Tag window reappears, and the name of the style you just created—“container”—appears in a field labeled Class.

In the Insert Div Tag window, click OK.

This inserts the new <div> tag and at the same time applies the style you just created. Now it’s time to take a look at your handiwork.

Choose File→Save. Press the F12 key (Option-F12) to preview your work in your browser (Figure 1-39).

Test the link to make sure it works. Resize your browser and watch how the page content centers itself in the middle of the window.

There’s one last housekeeping chore to attend to. If you look at the Files panel, you’ll notice that there are two web pages, three graphics (.png files), and a text file. Most web designers like to organize graphics files into folders to keep them in one place. You could create a folder in Windows Explorer or the Mac Finder, but why bother when you can do it directly in Dreamweaver?

In the Files panel, right-click (Control-click) the Site folder listed under “Local view” (circled in Figure 1-40). From the drop-down menu, choose New Folder.

Dreamweaver adds a new “untitled” folder to the files list and highlights the name, ready for editing.

Figure 1-40. Dreamweaver’s Files panel is more than just a way to see all the files in your site. You can use it to open a file (double-click the file name), rename a file (click the file name, pause, and then click the file name again), add folders (right-click on a file or folder and choose New Folder), and move files around (drag a file into a folder, for example).

Type images to name the folder, and then press Enter (Return).

The folder might still read “untitled” if you click elsewhere in the program before you edit the name; doing so deselects the folder. If that happens, simply click “untitled” to select the folder, pause a moment, and then click “untitled” again to highlight the name so you can change it.

Now you just need to get your images into this new folder.

Ctrl-click (⌘-click) the three image files (bg_page.png, logo.png, and map.png) to select them, and then drag them into the images folder.

The Update Files window appears, letting you know that by moving these files, you’ll affect the index.html and map.html files. That’s because those pages use these images. Normally, moving a web file that another page uses breaks the link between the files. Fortunately, Dreamweaver’s smart enough to update the links so they still work.

Click Update.

Dreamweaver quickly updates the web pages so that they now reference the new location for the three images.

Choose File→Save All to save all the changes you just made.

The Save All command is an invaluable tool. It saves any changes you’ve made to all opened files.

Congratulations! You just built your first web page in Dreamweaver, complete with graphics, formatted text, and links. You’ve even used one of Dreamweaver’s site-management features to create a new folder and organize your site’s files without breaking them! If you want to compare your work with the finished product, go to Chapter01_complete in the Tutorials folder and load the file index.html.

Much of the work of building websites involves the procedures covered in this tutorial—defining a site, adding links, formatting text, placing graphics, creating styles, and inserting <div> tags. The next few chapters cover these basics in greater depth and introduce other important tools, tips, and techniques for using Dreamweaver to build great web pages.

Tip

To get a full description of every Dreamweaver menu, see Appendix B.

Get Dreamweaver CS6: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.