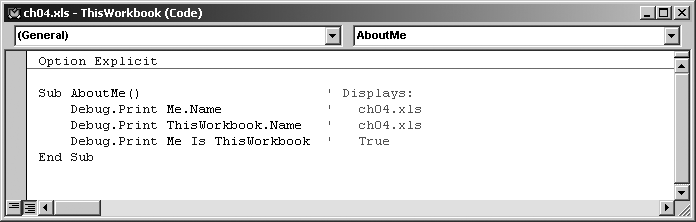

The Visual Basic Me keyword provides a way to refer to an instance of the object created by the current class. I know that’s a little confusing; here’s how it works: if you write code in the ThisWorkbook class, Me is the same as ThisWorkbook, as shown by Figure 4-11.

If you write that same code for one of the Worksheet classes, you get a different result as shown by the following code:

' In Objects sheet class.

Sub AboutMe( ) ' Displays:

Debug.Print Me.Name ' Objects

Debug.Print ThisWorkbook.Name ' ch04.xls

Debug.Print Me Is Sheets("Objects") ' True

End SubThat’s because Excel creates an object out of the class at runtime, and Me refers to that object. You can use Me to refer to members of the class using the dot notation:

Sub DemoMe( )

Me.AboutMe ' Calls preceding AboutMe procedure.

End SubYou can’t use Me in a Module. It’s valid only in classes since it refers to the instance of the object created from the class and modules don’t have instances—modules are static code.

Excel provides a number of properties that return objects that currently have focus in the Excel interface. Some of these properties were included in the list of shortcuts shown in Table 4-1, but they bear repeating in Table 4-3.

Table 4-3. Active object properties

|

Property |

Returns |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Name of the default printer in Excel (not an object) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Selected item (may be a |

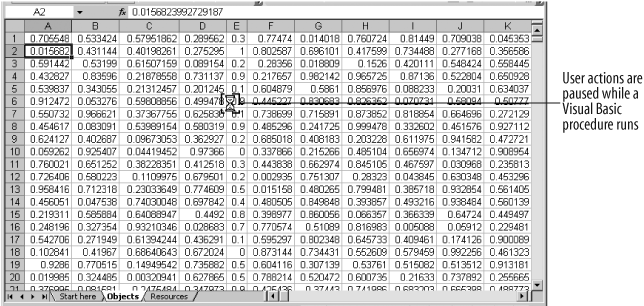

These properties are very useful in code because they tell you what the user is looking at. Often you’ll want your code to affect that item—for example, you might want to display a result in the active cell. Normally, the user can change the active object in Excel by clicking on a worksheet tab, switching to a new window, and the like, but she can’t do that while a Visual Basic procedure is running, as shown in Figure 4-12.

Code can change the active object, however. Many objects provide Activate methods that switch focus within Excel, and some objects, such as Window, provide ActivateNext and ActivatePrevious methods as well. If you rely on active objects, you need to be careful about changing the active object in code.

Many Excel programmers rely on activation a little too much in my opinion, as shown here:

Sub DemoActivation1( )

Dim cel As range

' Make sure a range is selected.

If TypeName(Selection) <> "Range" Then Exit Sub

For Each cel In Selection

' Activate the cell.

cel.Activate

' Insert a random value

ActiveCell.Value = Rnd

Next

End SubIn reality, there’s no good reason to do this since you’ve got a perfectly good object reference (cel) that you can use instead:

Sub DemoActivation2( )

' Make sure a range is selected.

If TypeName(Selection) <> "Range" Then Exit Sub

Dim cel As range

For Each cel In Selection

' Insert a random value

cel.Value = Rnd

Next

End Sub

DemoActivation2 runs faster because it avoids an unneeded Activate step in the For Each loop. There’s nothing wrong with using the active object when you need it; I just see it overused a lot.

Get Programming Excel with VBA and .NET now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.